A Grand Vision

The Queensland government funded Beerburrum Soldier Settlement Scheme was a disaster. The aim was to provide repatriated servicemen from World War I with farms where “swords could be transformed into ploughshares” for a tranquil existence in a rural climate.

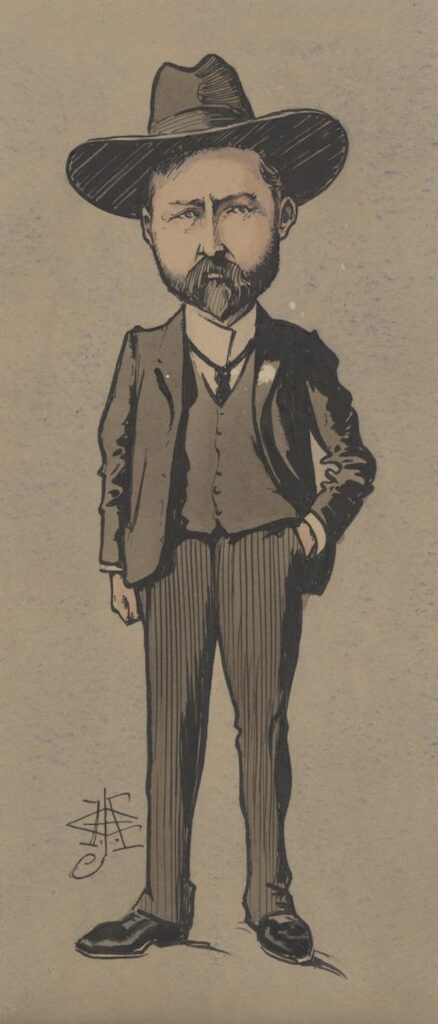

The high enlistment numbers and enormous physical and mental casualties from the war, forced Australian authorities to develop a repatriation policy. The concept of a soldier settlement scheme was developed well before the war ended. As early as July 1915, the Commonwealth Minister of Defence George Pearce (later Sir George) announced the creation of a Federal Parliamentary War Committee to address several matters, including the future of returning servicemen. Their main focus was to assist employment opportunities for those capable of “returning to normal civilian life” and to establish a register for those who wanted to “settle upon the land” at a reasonable cost.

The promising start

A survey of returning servicemen revealed that 25 per cent – about 40,000 men – welcomed the opportunity to become farmers, even though few had any previous farming experience.

Queensland saw the soldier settlement scheme as a means to secure federal funds for basic infrastructure to support the state’s broader planned development projects. However, negotiations between the Commonwealth and the Queensland government revealed a significant hurdle.

Queensland feared the Commonwealth would take the opportunity to influence their land use policies. Whereas all the other states agreed with the Commonwealth’s proposals, Queensland refused to reach an agreement mainly through their unwillingness to accept Commonwealth control over how funds were spent. Instead, Queensland went on its own and was the first to set up its soldier settlement schemes at Beerburrum and Pikedale near Stanthorpe.

The passing of Queensland’s Discharged Soldier’s Settlement Act in February 1917 stipulated that soldier settlement could only be held under leasehold tenure, as opposed to freehold, and that grazing areas were excluded. The grand vision was that these settlement farms would significantly contribute to Queensland’s potential to be the “food basket of the nation” based on its agricultural values being “among the highest in the world”.

Choosing the Beerburrum experiment

Queensland’s Minister for Public Lands, John Hunter, specified that areas chosen for soldier settlements had to meet specific conditions – fertile soil, adequate water, proximity to railway communication and markets, and free from pests.

Hunter’s Under Secretary was the first to highlight the availability of suitable land surrounding the Beerburrum railway siding. About 20,000 hectares of poor-quality dry sclerophyll forest and wallum heath was leased by the Commonwealth in 1912 as a military reserve. The state government retained the right to resume the land if it was required for state purposes.

Consequently, an area from the Glasshouse Mountains in the north, south to Elimbah and east towards Pumicestone Passage was chosen for a soldier settlement scheme, with the focal point being the small township of Beerburrum situated on the railway. The preferred crop was pineapples.

The area’s soil was sampled by the department’s Stuart Cameron, assisted by Joseph Rose, who offered his services. Rose was a pineapple farmer from nearby Woombye to the north. Here, pineapples and other fruits flourished in the rich volcanic soils. However, the soils at Beerburrum were much different. That didn’t stop Rose and the department from advocating pineapples as the preferred crop for the soldier settlers.

In hindsight, it is evident that determining the suitability of the soil and crop at that time was based on a flawed method of only assessing soil colour and acid content. In their report, Cameron and Rose argued:

“In all places tested and where samples were taken, the soil was of a loamy and sandy nature to a good depth and easily dug with a spade to a depth of eighteen inches. It would be very easy to work and while naturally well drained, should retain moisture sufficiently and would give quick results with fertilisers … the soils are all very similar in their character and chemical constituents, that they are deficient in organic matter and plant food, but that they are in an excellent mechanical condition for the growth of citrus fruits, pineapples and vegetables, and will respond readily to the application of suitable manures”.

A staff surveyor divided the area into individual holdings varying in size from 20 to 40 acres. One of the biggest hurdles at Beerburrum was the heavily timbered country, which had to be cleared. However, it was the presence of the railway that swayed the government to favour opening a scheme at Beerburrum.

Training Farm

Because they knew most of the men who had applied to join the scheme had little farming experience, training or state farms were considered ideal to compensate for that lack of knowledge and help the soldiers adapt to a new life.

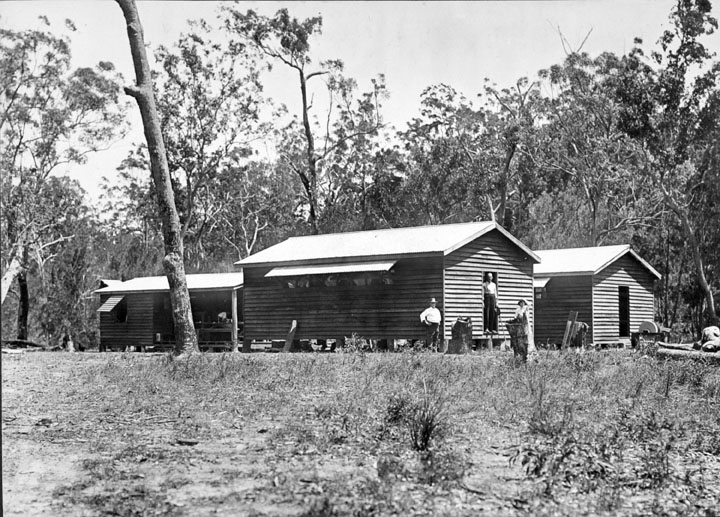

In September 1916, Rose organised the development of a 259-hectare training farm at Beerburrum. He assured the government it would only cost £100. He selected equipment such as tree winches and timber jacks to assist in the clearing operations. Light “structures made of round bush timber” were built to accommodate the early trainees. Labor gangs of ex-servicemen were employed to carry out the clearing.

Just to add to the absurdity of the whole scheme, the initial intake consisted of nine servicemen who were amputees, and some had just spent 12 months in hospital. Despite being considered unfit for military service, no one questioned their fitness to be independent farmers in the sandy soils around Beerburrum.

However, the problem was that those placed to do the training were also inexperienced and lacked knowledge of subtropical fruit culture. The Beerburrum training was just an agricultural research experiment for the Queensland government. For example, it was later realised that fertilisers had too much phosphoric acid, damaging the pineapple.

The struggles begin

Many returned servicemen were sent to Beerburrum to try their fortune. Even immigrants from Europe were part of the intake.

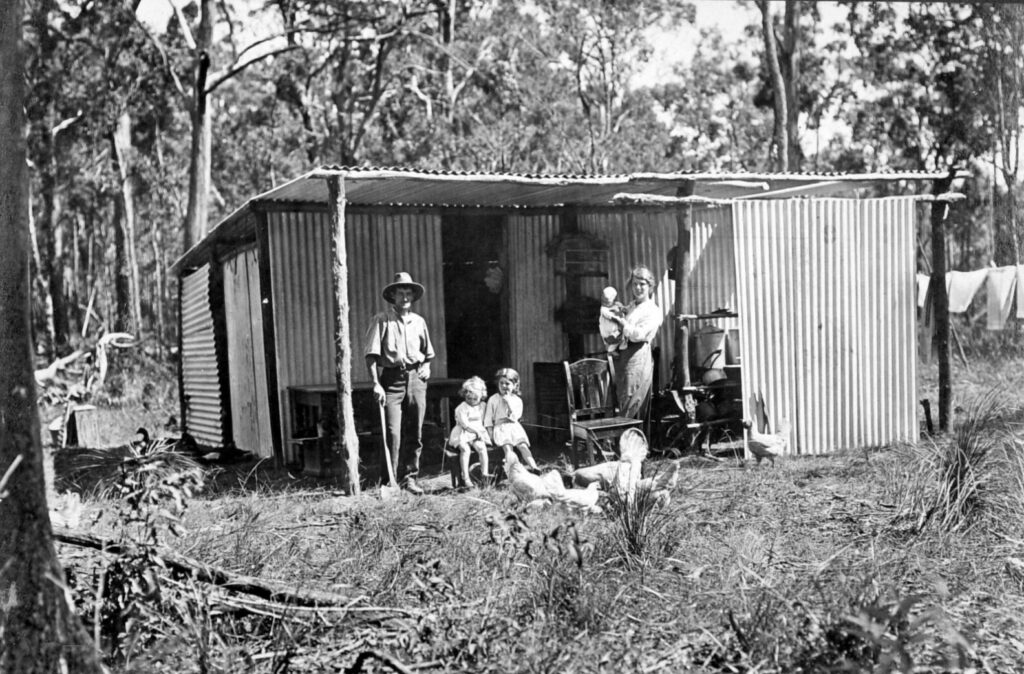

By November 1916, 4,695 hectares had been subdivided into 320 holdings. Ballots were held, and 21 men who had been invalided back to Australia were chosen to select a block. Within three months, 19 of these settlers protested over the conditions of their tenure. Instead of offering returned war heroes the promised freehold, they were given perpetual leaseholds, which only added to their financial hardships.

The Beerburrum scheme involved the clearing of 44,000 acres of forest. The cost of clearing three acres of their selection was deducted from their advance. Because of their disabilities, many relied on paying contractors to do the clearing. Soldiers sometimes formed cooperative “gangs” to pool their wives and children to assist with duties. They removed large stumps with gelignite, roots were grubbed out, stacked and burnt, and the hole was filled with a shovel.

After the first 12 months, 150 acres were cleared, 60 acres were under cultivation, and 20 houses were built. The ground was prepared with a single mouldboard plough requiring horsepower. However, there was a shortage of horses, and those who managed to get a horse or two, faced high feed costs due to the lack of adequate fodder. Dairy cattle were virtually non-existent as the cost was too high, meaning families had to live off condensed milk.

Settlers continued to arrive as numbers doubled to 48, lured by arrangements that were too good to be true. The main issue was the planting of pineapples on marginal land. At the same time, the market was saturated.

In August 1920, the Prince of Wales was given a short tour of the soldier settlement as part of his Australian tour. His party of dignitaries were confronted with “quite a number of soldiers, each with a wooden leg, who hobbled past.”

After planting, the pineapple crop had to be carefully tended for two years before harvest because of their shallow root system and inability to compete with weeds. Fertilising was another requirement, and after a suitable blend was made for the local conditions, many settlers found they couldn’t afford the cost and went without. Failure to use fertiliser saw a gradual decline in quality over the next decade. The government tried to assist by advancing loans to settlers to purchase sufficient fertiliser. However, the loan was repaid with a lien over the crops, further reducing income.

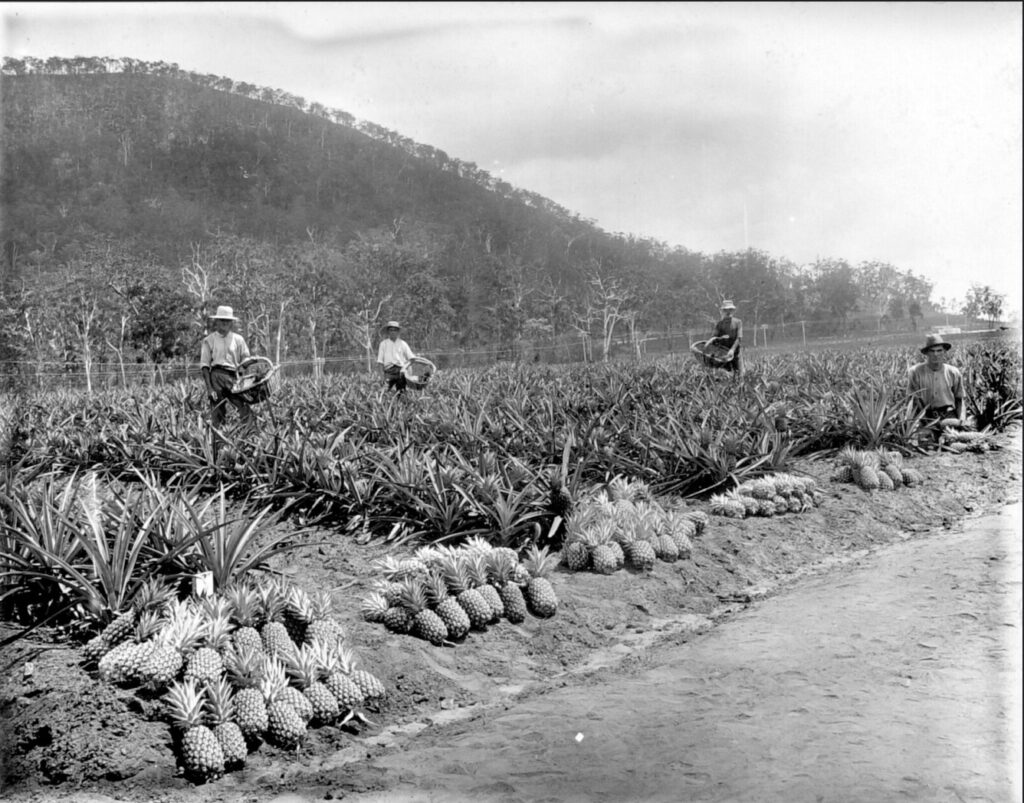

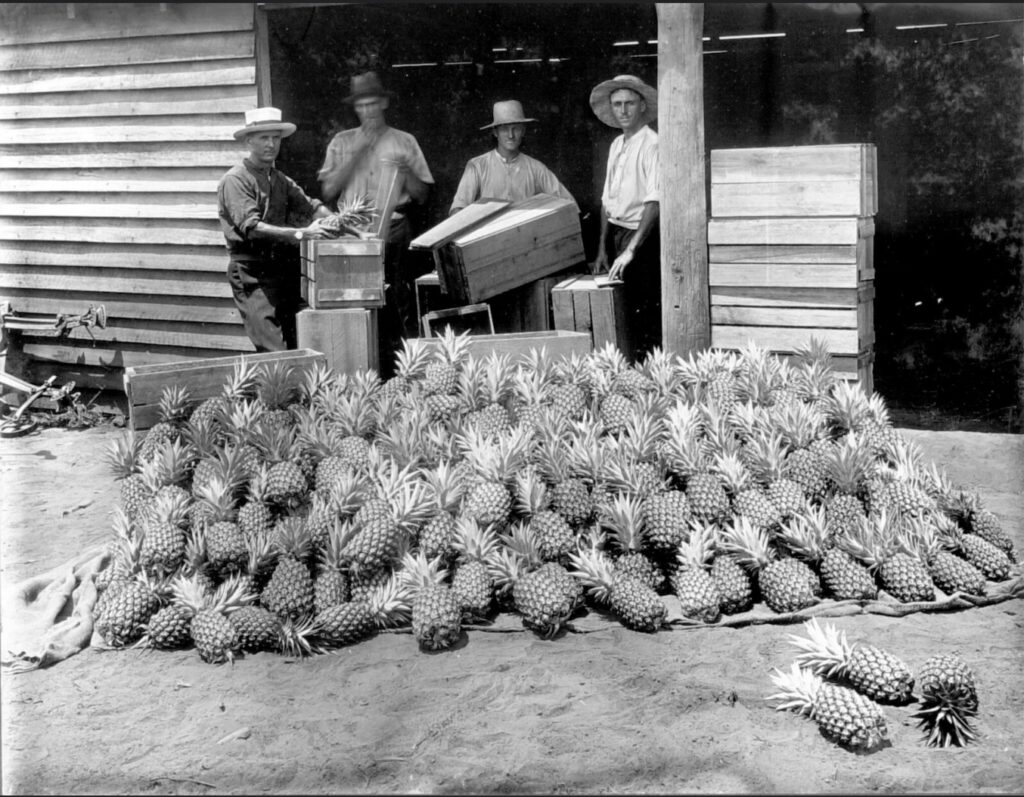

Harvesting was also a labour-intensive operation. Pineapples were picked, placed in cane baskets, and emptied onto a slide at the ends of the planted rows. A horse drew a slide filled with pineapples to the farm shed where the fruit was graded and packed into timber cases, protected from bruising with dry blady grass, and then taken to the railway siding.

World War I reduced the supply of imported timber for cases, and the Department of Forestry was forced to experiment with local species. A few were found to be suitable but at a much higher cost.

The government forced the soldier settlers to plant at least two hectares of their selection with pineapples. Suckers were used instead of tops to enable rapid growth. The suckers were purchased from friends and associates of Rose’s at Woombye, providing a tidy profit for the established growers on much better soils. However, in October 1919, the Woombye farmers demanded a 33 per cent increase in suckers. When the government refused to accept that price, the suckers were withheld, bringing planting to a halt.

In response, the government officials advised the soldiers to fence off at least one hectare to grow peanuts as an alternate crop, only to be told later that the officials had no idea how to cultivate peanuts.

The government built a general State store and butchery in January 1917 in anticipation of rapid growth. The store aimed to keep prices low for the soldiers and their families. But, by 1919, it became known that the store had profited at their expense.

The cannery – a double-edged sword

The government always had plans to assist the Beerburrum soldier settlers by constructing a state cannery. It was all part of a broader Queensland Labor Party’s socialist strategy of establishing state-run businesses to out-compete private monopolies. The government genuinely believed they could run a business better and keep prices lower. Their motto at the time was to make the:

“capitalist system work in the interests of the many and not of the few”.

They acknowledged that the fresh fruit market was oversupplied, and the government recognised they had a duty to ensure the soldiers they enticed into farming received the highest possible price for their goods.

Rose, as Supervisor of the Beerburrum Soldier Settlement Scheme, and James Sparkes, the Works Manager of the proposed cannery, carried out an overseas scoping tour in Hawaii and California and recommended that a cannery be built in Brisbane to cater for the produce from the Pikedale settlement scheme as well.

The cannery opened in January 1920, just in time to process the summer crop of pineapples. The Beerburrum settlers supplied 23,000 cases of pineapples at a protected price of six shillings a case, well above any market price. It coincided with a serious post-war slump in Britain’s demand for Australian fresh produce.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t only marketing issues that plagued the cannery. The plant was overcapitalised, and it was quickly realised that the new plant had failed to install the most modern equipment, which still necessitated a lot of manual labour. Consequently, production costs were high, and the final product was inferior to cans of pineapples out of California.

In Britain, they found inside tins:

“Packing was all wrong. Very small pines had been used, certainly all one size, but the tin was too large for the fruit, so they packed pieces around the sides. It looked slovenly”.

To try and overcome its reputational problems, the cannery refused to accept undersized fruit. However, the undersized pineapples were mainly due to the lack of fertiliser. Settlers were under pressure to follow the “scientific methods of cultivation” despite having no money to pay for regular fertilisation. With 60,000 cases expected to be harvested in 1920-21, the Commonwealth provided a loan to the cannery. This was equivalent to a subsidy of seven shillings six pence per case. Growers received five shillings per case, but the smaller pineapples were still rejected.

The following year, the cannery dropped the price per case by two shillings, which put the growers under increasing financial ruin. The state government was forced to provide a subsidy of one shilling per case.

Behind the rose-coloured glasses

Meanwhile, Beerburrum’s population peaked in 1921 at 1,200 people. The soldier settlers tried their hand at other crops to reduce their dependence on pineapples, and the government painted a rosy picture of the scheme. But in reality, it was much different. The roads from individual selections to the railhead were impassable every time it rained. Struggling families relied on a sustenance allowance to survive.

The government looked at alternate fruit processing options. When J. H. Morton, who had built several dehydration plants in England, arrived in Australia in 1920, the Beerburrum soldiers showed interest in getting such a plant built to wean themselves off their total dependence on the cannery.

A Cooperative Company was established with some settlers as directors. Morton gave a practical demonstration of dehydration at a Brisbane Exhibition, insisting that pineapples were the easiest fruit to dehydrate. The Cooperative made plans to build a dehydration factory at Nambour. Not surprisingly, the state government lacked any enthusiasm for this process as it would potentially negatively impact the cannery. After the government enquired about the dehydration process in England, they claimed the results were discouraging, citing the failure of several companies abroad.

Funds to build the new factory ran out before it was completed. With the government unwilling to assist, the directors issued more shares to raise capital. Limited operations started in April 1923, treating pineapples, bananas, quinces and apples. However, output was too low to keep the company viable. The failure to produce commercial quantities meant the high hopes of an alternate market for their produce were dashed. By 1925, the machinery lay idle, and the main building was used to store sawn timber.

Meanwhile, the cannery expanded into producing jams, sauces and jellies to boost profits. But it wasn’t enough. Half the workforce was dismissed in the winter of 1921 as the cannery couldn’t sell its processed summer crop. Growers wanted assurances that the cannery would purchase their next crop, and in the nick of time, sales suddenly picked up in Britain. But that turned out only to be a stop-gap reprieve.

The cannery couldn’t compete with the lower priced tins of pineapples from Hawaii into the USA market; they were plagued with quality issues, with many stocks of canned pineapples returned from Western Australia due to poor state of the contents and blown tins.

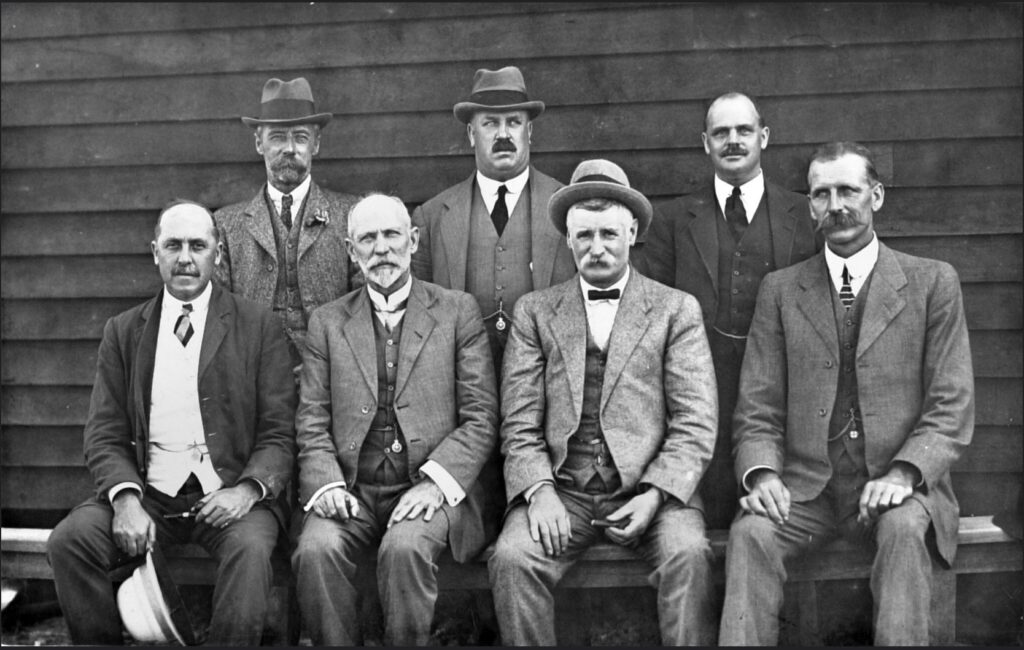

After many repeated representations by settlers to government members, the government set up a Soldier Settlement Revaluation Board to look at improvements in the settlement schemes.

The 1923 Crisis

The cannery lost £10,000 in 1922 and faced further cost pressures. The Beerburrum settlers insisted on receiving four shillings a case to cover their costs and make a decent living. The cannery only offered two shillings, nine pence per case. Each settler was burdened with an outstanding lien from the previous year’s fertiliser costs, interest payments on their loans, living expenses and horse feed and faced ruin. The state government continued the subsidy of one shilling per case. Settlers were encouraged to supplement their income with other crops such as papaws, passionfruit and peanuts. Citrus proved somewhat successful and, in 1923, provided much-needed income. But that was only fleeting as that hope declined rapidly in subsequent crops, as trees were attacked by insect pests and suffered many diseases.

By the middle of 1923, things were desperate. Some farmers turned to selling directly to consumers, offering to deliver to their door anywhere in Queensland. It was a good way of selling undersized pineapples that would have only rotted. But again, the early promise and optimism were flagged by the lack of sales and the limited marketing.

The cannery advised that they would only pay two shillings six pence per case for the upcoming summer crop. This was well below the cost of production. They also stipulated they would only receive up to 15,000 cases, even though settlers had been coerced into using fertilisers to boost production and pineapple size. Despite being set up expressly to can fruit grown by soldier settlers, the economic imperatives of the cannery were foremost to the managers trying to run a profitable business compared to the private canneries that could run at a profit.

The sustenance allowance was also discontinued, forcing many families to become destitute. Many soldiers were forced to look for work elsewhere, leaving their families on the farm. Then there was the October bushfire, where a couple of houses were burnt down.

The number of soldier settlers had dropped to 293, with 117 selections lying abandoned. It was becoming apparent that many selections were not productive. The soils were impoverished after five to six years of cropping, with yields declining dramatically.

There were pockets of better soil, and in these areas, farmers persisted and even trialled sugar cane, and others diverted into growing vegetables.

In October 1924, the confidential report of the Revaluation Board painted a horror story, concluding that the Beerburrum Soldier Settler Scheme would never even be a moderate success. The government tried to publicly gloss off the inadequacies, blaming the problems on a few disgruntled farmers who refused to improve the cultivation of their land after it had been cleared and planted for them, even though that was not the case.

The farmers had hoped the Revaluation Board would highlight the government’s pledge of transferring soldier settlers on unproductive land to new districts with better prospects. Instead, it recommended writing off current debts, hoping the problems would disappear.

Plodding on

The 132 soldier settlers still farming in late 1926 held out hopes that subsidiary crops such as sugar cane and citrus fruits would prove profitable. However, both crops were devastated by drought towards the end of the year.

Surprisingly, the pineapple crop that summer was bountiful, and there was heavy demand from consumers. For the first time in years, there was no glut of pineapples on the market.

The good times didn’t last long, and the 75 farmers still left in 1928 had survived due to cash advances from the government, with the likelihood of repayment very slim. As the Depression hit in the early 1930s, there were only 35 farmers left.

Sadly, the grandiose visions of group settlement in the Beerburrum district back in 1917 were in tatters. One politician predicted this in parliament, saying:

“many a returned soldier will break his heart on that wretched land on which it is proposed to put him today”.

Officially, Australia’s first post-World War I soldier settlement at Beerburrum was terminated in 1929. Yet, in 1932, the government distributed tung tree seeds, native to China, to surviving Beerburrum farmers to test the district’s viability for cultivation. Tung tree oil was popular as a wood-finishing oil and was extracted from the nuts. An inspection two years later sang its praises, but nothing further was heard of that idea again.

During the depths of the Depression, the government placed destitute unemployed families on abandoned Beerburrum selections, and they were expected to grow tobacco despite having no farming experience. By October 1932, 94 men arrived, including 38 families, and were supervised and supplied by the Department of Agriculture. While 1932 was very dry, the following two years were very wet, damaging plants and encouraging the spread of pests, including blue mould and nematodes.

A miserable failure

While the concept of rewarding servicemen by providing land to make a living from as part of their post-war recovery, the tragedy was the soldier settler schemes failed to provide the good intentions initially planned.

The Beerburrum Soldier Settler Scheme, once a beacon of hope, turned into a symbol of broken promises and unfulfilled dreams. The grand vision of transforming soldiers into successful farmers on less-than fertile land was marred by poor planning, inadequate support, and relentless economic pressures. The legacy of Beerburrum is a stark reminder of the importance of realistic planning and genuine support for those who gave so much sacrifice in defending their country.

Another interesting account of just how many of patriotic soldiers were let down after returning home from fighting in the 2 world wars to protect their countries. Thankyou Robert

Tibrogargan Lodge #305, United Grand Lodge Queensland, of which I am a 51-year member, was established at Beerburrum on 12 March 1923. The majority of the 28 Foundation Members were returned soldiers. The inaugural Secretary was Dr Reg Bower, the superintendent of the local Beerburrum Hospital.

It certainly was a tough start given the extreme socioeconomic, physically and mentally demanding, testing environment. But these were real men, hardened in the hills of Gallipoli and the trenches of the Western Front. No better Lodge foundation could have been built.

Tibro celebrated its 100th birthday last year and with the entry of six new members through the year the future looks positive.

Thanks, Robert. You always provide a factual read.

Gary

Gary, I am really glad to hear there is still some connection that persists today.

An objective if sorry account of yet another failed soldier settlement scheme. Beerburrum was not the only one.

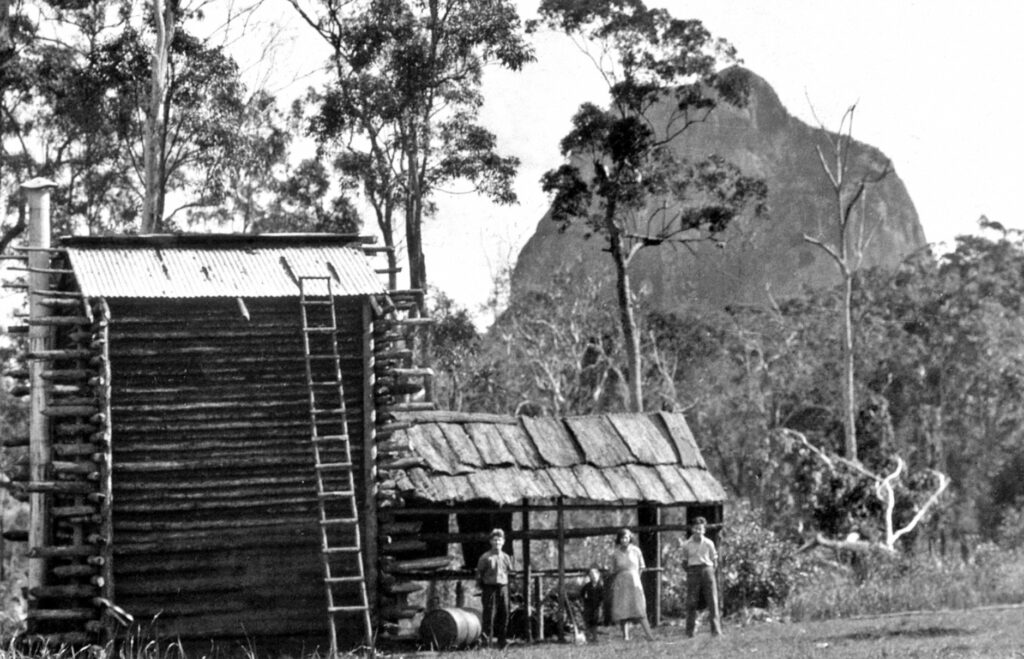

Robert, why the picture of old fellers planting pines? These were pine trees, not pine apples.

Not relevant to your story as told but you omit the follow up when most of the SS leases were taken over for pine (tree) plantations; some blocks were planted to eucalypts mainly blackbutt and tallowwood. This photo records some of the earliest experimental southern pine tree plantings by the Queensland Forest Service at Beerwah by a visiting group of dignitaries.

The extensive plantations in the Beerburrum/Beerwah area developed from these early 1932 plantings. Sold for a song by the Qld Govt to Hancocks, a Canadian superannuation entity;

another sorry tale of Qld govt bungling.

Ian Bevege

The caption says planting pines not pineapples, but I see what you mean. I will change it to pine trees!

But you raise a good question.

I did have a short paragraph about planting pine trees and the eventual development of the extensive plantation estate. However, I must have removed it from earlier drafts and it missed going into the final version. That being the case, I should have removed that really good photo, as it is irrelevant to the story I presented.

I am toying with writing a follow up about the development of the pine plantations. Perhaps I should, as you have highlighted its importance in Queensland forestry history. I just need to work out an angle for the story that no one else has covered.