This is a story about a quietly spoken Dutchman who had responsibility for setting up and maintaining a radio communication system in the early days of AFH when access to Surrey Hills was much more limited than today.

The radio system was the only form of communication between the administrative office in Burnie and the workers in Surrey Hills. It was vital in times of machinery breakdowns, bushfires and accidents.[1]

When Matthew Flinders sailed the Bass Strait in December 1798 to confirm Tasmania was separated from the mainland, he saw a distinctive peak while sailing east from Table Cape:

“The sole remarkable object inland, was the flat-topped peak, which had very much the appearance of an extinguished volcano.”[2]

He named it Peak like a Volcano. The Van Diemen’s Land Company’s (VDL Co.) surveyor, Henry Hellyer, attempted to climb the mountain on St Valentine’s Day 1827, but he got washed out by heavy rain. He returned to the base and camped in the shelter of a large tree and the next morning made it to the summit and took observations for his panoramic sketch. Although the mountain is named in honour of Hellyer’s climb and discovery of Surrey and Hampshire Hills, Hellyer’s last plan and map of the area in 1832 shows the mountain referred to as ‘Peak like a Volcano’ in deference to Flinders.[3]

After the VDL Co. sold Surrey Hills to Gerald Mussen and his financial backers for its timber, Associated Forest Holdings (AFH) systematically introduced forest management across its Surrey Hills estate in the mid-1950s.[4] Soon after, AFH recognised a need to invest in emerging technology to assist in communications. There were few roads, and staff camped in the bush or at the isolated Guildford Junction. These remote workers had to communicate with management in Burnie regularly for supplies during breakdowns and report on progress. Logging operations were also underway, and there were safety concerns about the remote and hazardous operations.

The traditional use of radios was problematic on Surrey Hills because of distances and rugged landscape. It was ineffective without a communication tower’s relay system.

St Valentines Peak towers over Surrey Hills at more than 1,200 metres above sea level. The steep rocky peak was inaccessible except on foot via a steep ridge track to the south starting at Peak Plain. It is regularly covered in snow during the winter months and receives the full brunt of strong, icy cold south-westerly winds. It was a tempting high spot for a Very High Frequency (VHF) radio network providing an uninterrupted wide arc for radio transmission. There was just one problem – the prospects of installing and operating a transmission tower in such a wild and inaccessible spot made it unfavourable.

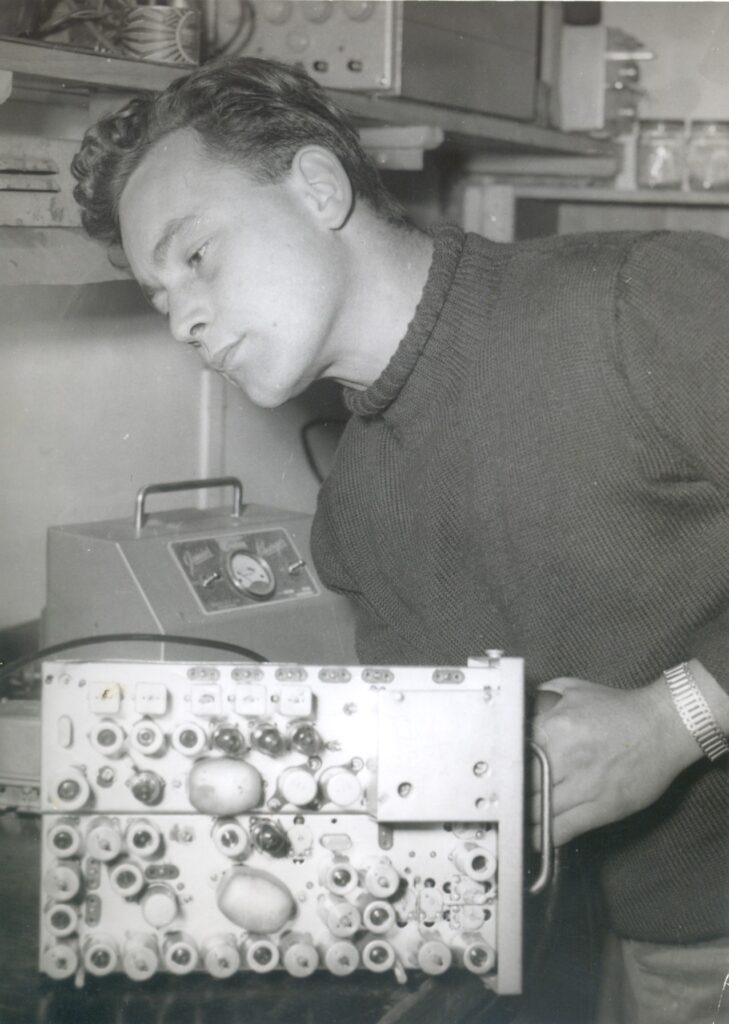

Amalgamated Wireless (Australasian) Ltd, a leading radio transmission company, had already designed an unattended relay station that could operate all year round from its own source of power. Developed during WWII, this technology was ‘cutting edge’ in the 1950s. It consisted of two complete FM transmitter receivers typically used in vehicles. AFH wanted a communications station that could provide communications with its company vehicles over a wide area, linked back to its head office in Burnie. With his electronics background, AFH employee Filip ‘Flip’ Wyker was given the task of establishing the radio station on top of Valentines Peak.

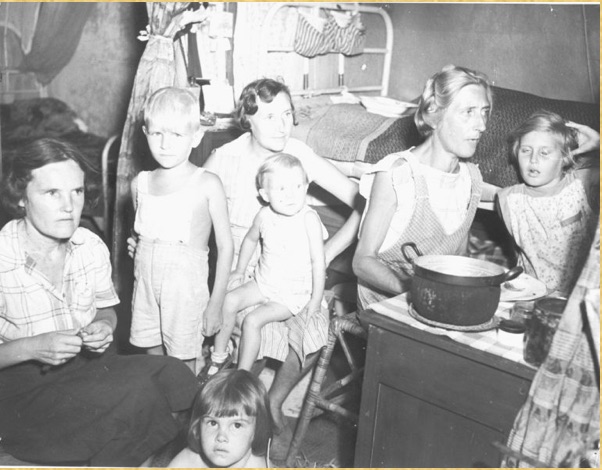

Flip was born in July 1930 at Drachten, Holland. His father was a school headmaster, and the family moved to the Dutch colony of Indonesia just before WWII. His father took up a posting at a local school. Unfortunately, along with other Dutch expats, the family found themselves interned camps after March 1942 when the Japanese invaded and occupied the country. These civilian prisoners were often treated as severely as the POW camps. What was worse, Holland, as part of the Allies, was forced to abandon the colony.[5] Flip wasn’t even twelve years old. His older brother and father were sent to Camp Ambarawa, Flip, his sister Elise, and his mother to the female’s and children’s concentration Camp Tjideng. After he turned twelve, Flip was transferred to the male camp. There was always a shortage of adequate food, and many internees died of starvation. Flip recalled how they had to be resourceful to survive. One story was after the Allied aerial bombing raid near the camps. Prisoners would collect dead pigs to supplement their meagre diet. They also grew what vegetables they could. Flip got into trouble a few times when he was caught leaving the camp to get food such as eggs from the neighbouring farms.

The family survived the camps’ horrors and were reunited after the war when Japan surrendered in August 1945. The Wyker family, like other liberated Dutch, had to wait for repatriation. During the Bersiap period, when Indonesian Merkado fighters fought for independence, there was cruelty and confusion. Eventually, they returned to Holland, and Flip finished schooling and training. He studied radio engineering, plumbing and building at middle school. His best marks, however, were in athletics. Like all Dutch at the time, he had to speak English, Dutch, French and German. Flip then joined the Navy and left after 18 months. He moved to Tasmania in 1952 to join up with his brother-in-law Dirk ‘Dick’ de Boer.[6] Not long after, his parents also emigrated to Tasmania.

Dick was instrumental in Flip finding work with AFH.[7] Flip started work on the Woolnorth Estate in the far north-west with the initial roading and logging operations. Unfortunately, while there, Flip suffered a severe injury to his leg while travelling on the back of a tracked machine. A limb lying on the ground flew up, knocked him to the ground, and the machine then ran over his leg. The injury was quite serious, and Flip’s doctor said, ‘I would let gangrene set in before I cut off his leg’. Fortunately, his leg did heal without any serious infection, but it did prevent him from pursuing active sports activities outside of work.

While he was recuperating in the hospital, Flip met nurse Lilian Stokes, known by her middle name Helen. Helen was born and grew up in Smithton on the far north-west coast. A courtship ensued, and the couple were married in April 1960. Helen actually has her own fascinating story as she is a direct descendant of Mannalargenna (c1750-1835), the chief of the Oyster Bay tribe in the north-east of Tasmania. One of his daughters, Teekoolterme, married sealer John ‘Long Tom’ Thomas.

Helen and Flip lived in the old Van Diemen’s Land Company house just out of Guildford, where Flip was in charge of the AFH stores. Flip and Helen spent seven years at Guildford, bringing up their three children, Willem (Bill), Rodney and Wendy. They enjoyed their time at Guildford, Helen recalling one year where they had a white Christmas. As with other residents living in a very isolated town, they learned to be resourceful with their vegetable garden. While at Guildford, Flip set up and maintained the wind-powered radio repeater station on St Valentines Peak.

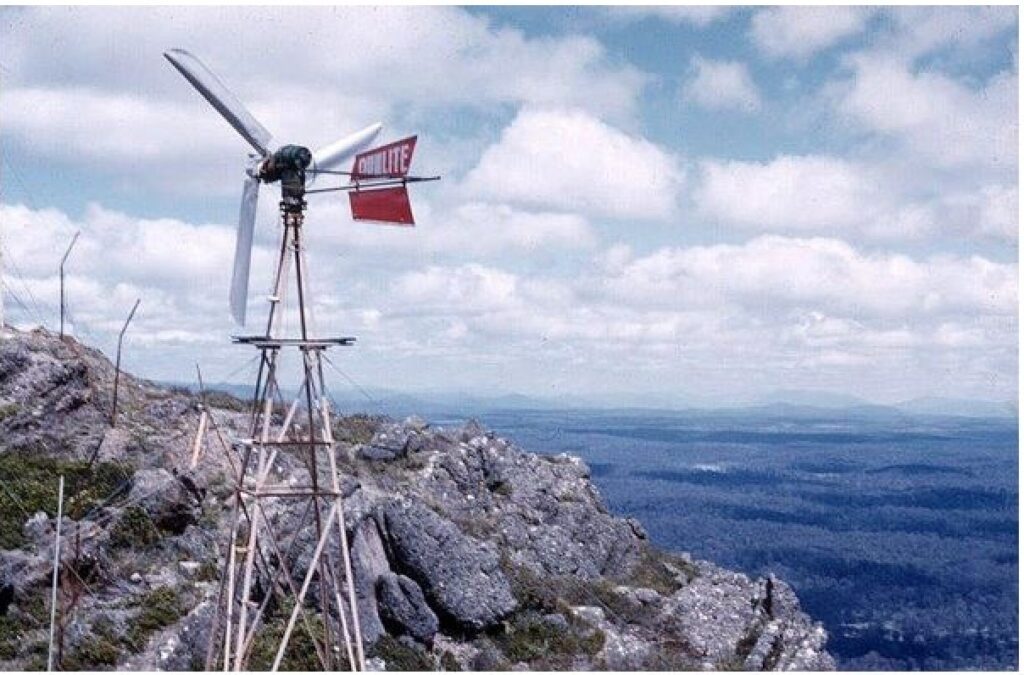

Amalgamated Wireless had to develop a system to work on St Valentines Peak without AC power. They designed an unattended relay station that could operate all year round from its own source of energy. The transmitter switched on only when a message was intercepted by the receiver connected to the transmitter. Two sets of transmitter/receiver units were installed and would automatically switch over if a fault occurred. A tone signal would be transmitted alerting Flip to a problem, and he would have to climb the Peak, regardless of the weather, to carry out the necessary maintenance works. Two wind turbines provided power for storage batteries. The system was set up to switch on and off by a time clock to operate during daytime hours between 6 am and 6 pm to save on power.

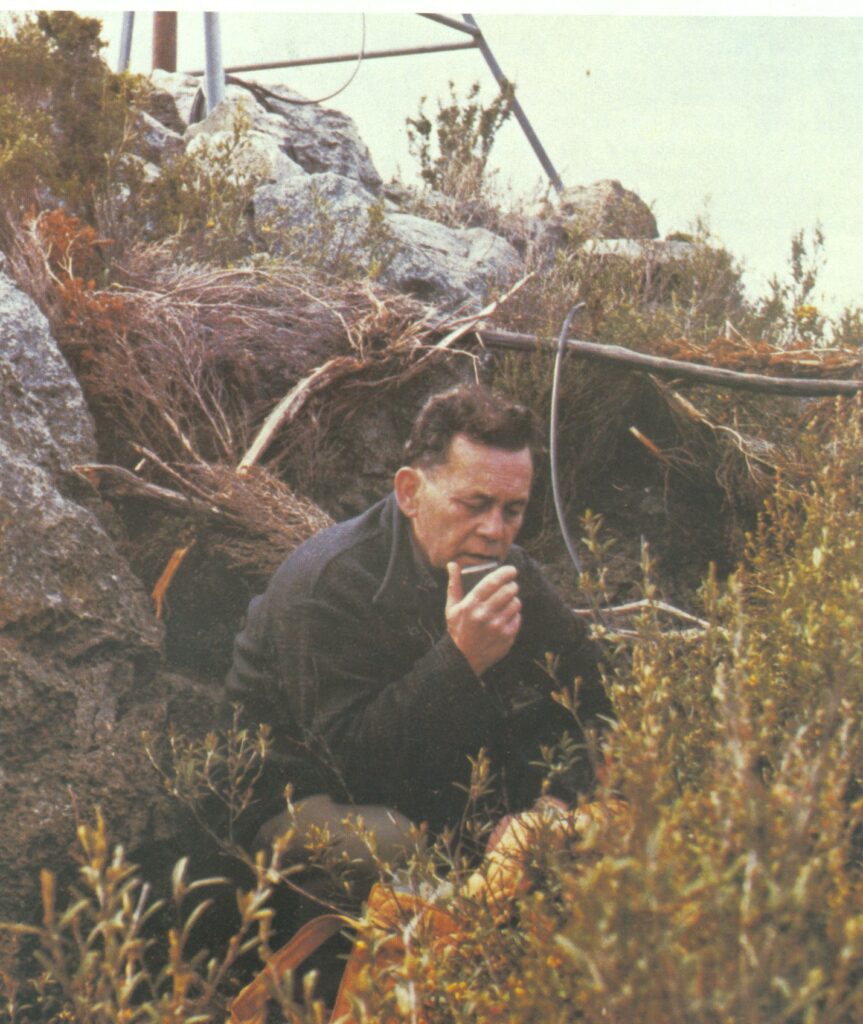

All the materials used for the site were carried to the top. Whenever there were problems with equipment or maintenance had to be carried out, Flip would walk to the top of the Peak. The weather on the Peak was extreme at times. Wind speeds could reach nearly 200 kilometres per hour, according to recordings made on the Peak. They are brutal when blowing vertically up the steep slope sides of the Peak. Many times, during winter, the Peak can be snowbound, and the aerials covered in ice. Flip walked St Valentines Peak a remarkable 204 times when the weather caused havoc with the equipment, a feat he managed despite his previous leg injury.

In the late 1960s, Telstra compulsorily acquired land on nearby Companion Hill for their communication needs. They built a road to the top of the Hill and set up a large transmission tower. Because of the easier access for maintenance, AFH decided to shift their base station from Valentines Peak to Companion Hill soon after. In the 1970s, when APPM expanded forestry operations to the north-east and south of the state, a 2-way radio link between AFH Burnie, APPM Tamar and TPFH Triabunna was developed to ensure radio contact could be maintained for all vehicles and machinery regardless of their location. To enable coverage across the state, seven repeater stations were situated in strategic locations between Smithton and Triabunna. Flip was involved in the testing of these sites. The Companion Hill base station was boosted by two additional stations at Mount Bischoff and Lileah. The AFH network was linked to Tamar via the existing station at Dazzler Ranger, and TPFH Triabunna was linked to APPM Tamar by a new repeater station at South Sister.

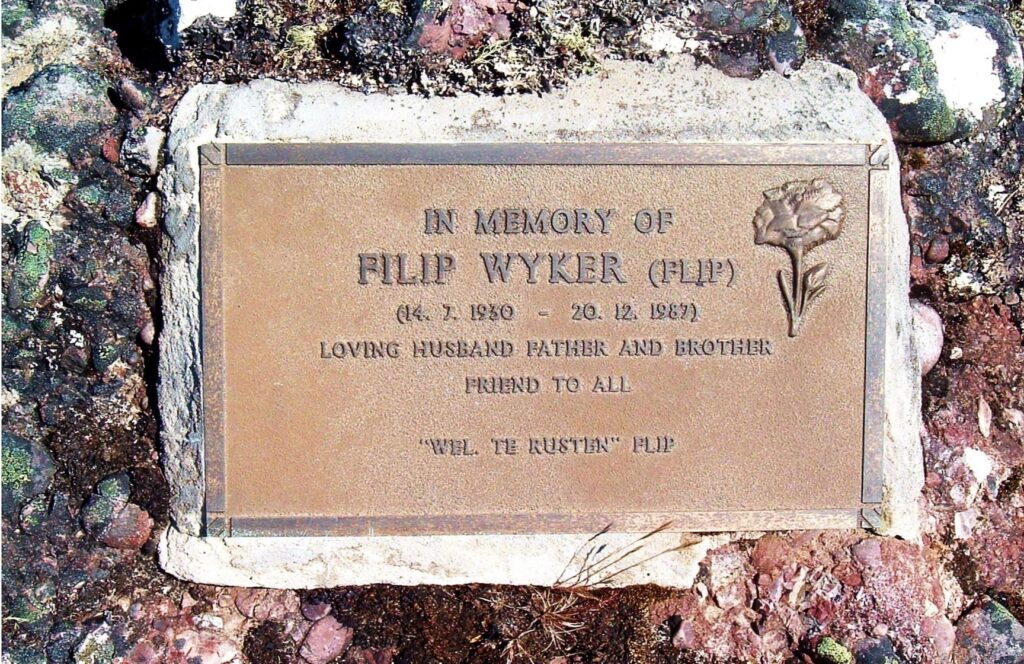

In the mid-1980s, Flip was given the task of setting up a computer network for AFH. While Flip wasn’t an IT person, his electronics knowledge was suitable for carrying out this task. It was difficult work for Flip and highly stressful, in part because he was colour blind and couldn’t differentiate between the coloured cords to correctly connect to the computers. In the later months of 1987, Flip complained of being a bit lethargic and sought medical advice. His doctor told him he was fit, and there was nothing wrong with his heart. Unfortunately, shortly after, in December 1987, Flip had a severe heart attack while at home. He died five days later at the hospital.

Flip was a quiet, unassuming gentleman and well-liked by his peers. Despite his poor leg, he was very active at the Ridgley Bowls Club, being the inaugural Treasurer. He also was a cricket umpire for the local competition. Flip was a devoted family man and never let the wartime horrors he experienced in Indonesia interfere with his later life. He used his building skills to meticulously build a much-loved family holiday shack at Sisters Beach.

The successful development of Surrey Hills during the AFH-era was dependent on an adequate communication system. Flip Wyker expended a lot of energy to ensure communications continued even after severe weather hit the prominent and exposed Valentines Peak. Flip’s ashes are on Peak Plain at the base of Valentines Peak, and there is a plaque on top of the Peak in his memory with the words “Wel Te Rusten”, Dutch for well resting.

[1] I am indebted to Helen and Bill Wyker and Winston Nickols for providing material about Flip, including photos, and the radio communications set up on Valentines Peak. Thanks also to Brian Rollins for clearing up the naming of Valentines Peak. Kay and Bill Wright kindly scanned some of Helen’s photos.

[2] Flinders, M. (1814) A voyage to Terra Australis. G & W Nicol, London

[3] According to Brian Rollins, Hellyer chose to retain the name ‘Peak like a Volcano’ because he may have been sensitive to the fact that Surrey and Hampshire Hills were proving a failure for sheep and the name St Valentines Peak was an uncomfortable reminder of his discovery about which he had been so effusive.

[4] Chapters 8 and 9 of my book “Fires, Farms and Forests” details the sale of Surrey Hills, the development of the pulp and paper industry at Burnie, and the formation of Associated Forest Holdings (AFH).

[5] At the time, Holland (The Netherlands) itself had been occupied by Germany since 1940 and had little opportunity to defend its colony against the Imperial Japanese Army. Initially, most Indonesians welcomed the Japanese as liberators. This changed when up to 10 million Indonesians were recruited as forced labourers. It has been reported that four million people died in the Dutch East Indies as a result of famine and forced labour during the Japanese occupation, including 30,000 European civilian internee deaths. Straight after the war the Indonesians proclaimed independence from the Dutch, but Holland sought to regain their colony. After a bitter diplomatic, military and social struggle, Holland finally recognised Indonesian sovereignty in December 1949, thus ending 130-year Dutch colonial rule.

[6] Dick de Boer left Indonesia in 1950 to start work at AFH. He managed the nurseries and was instrumental in the development of eucalypt plantations on Surrey Hills and pine plantations on AFH land. More details about Dick can be found in my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, particularly Chapters 9 and 11.

[7] Helen Wyker mentioned she has a piece of paper kept by Flip and believed to be written by Reg Needham. The only words are “have no work for this bloke”. I believe de Boer had made representations to get Flip work at AFH, which initially was unsuccessful.

Another great job Robert. Further to your excellent article regarding Flip and Valentines Peak, I have one or two more memories to share.

Flip was also an ardent Wynyard (Cats) football supporter. He loved and owned VW Beetles. Ond day Flip drove me from the AFH office to pick up RHN’s wine red Customline at the then City Motors Ford dealership. On our return we raced along Wilson Street behind the EBR yards and the bugger beat me in his little grey VW! I think we did exceed the speed limit by quite a bit..!!

I don’t recall there being two Dunlite wind-mill generators on V/P during my time with the company, for at that time many of my trips involved going up to recharge the batteries with a little petrol driven generator after a period of little or no wind. During one violent storm not long after the radio system was installed, the whole generating assembly was ripped off the tower landing somewhere down the east flanks of the ‘Peak’…I scrambled around several times on the lower slopes but found nothing.

Most of the BB&T staff were involved in establishing the radio shack, fencing and windmill tower on the Peak. This involved wheel barrows, water, cement and building materials et al. Tiff Stubbs pushed a trail as far as he could off Peak Plain up the first ridge with a Cat D7. A great team effort overall.

Ironically Robert, one of the first structures I noted when first arriving in Prince George, BC back in 1973 was a Dunlite windmill generator in an industrial park…!

BB&T was the second organization in Tasmania to install a 2-way VHF repeater system. The State Police Department were the first.

Cheers,

Barry

Thanks Barry for the additional information. The damage to the whole generating assembly shows just how bad the weather conditions could be on the Peak.

It’s good to see that you have now written up Flip’s story and the VHF radio repeater on Valentines Peak. It’s a great story, worthy of recording.

I started with AFH on 3 July 1985, so overlapped with Flip until his passing. Like my colleagues, I was shocked to come in on a Monday to discover that Flip had passed away during the weekend. I recall it was very close to Christmas which must have made it that much sadder for his family.

I didn’t realise that AFH had installed wind generators to charge the batteries on the Peak. The Dunlite looks very much like the wind generators some cruising yachts now use to maintain their batteries. I didn’t realise that technology had been around for so long!

The story I’d been told (third/fourth/… hand – therefore not very reliable) about Flip’s trips up and down the mountain was that he went weekly, year after year, carrying up an old fashion flooded lead-acid battery that had been on the charger all week at Ridgley and bringing down the discharged battery to be recharged. Like the fisherman’s catch, that battery got bigger and bigger in the telling as the years went by! I struggled to picture someone doing that week in and week out! Seems like he may not have. I notice Barry comment that he mentions using a portable petrol generator. Now that makes much more sense!

Maybe both stories are correct – initially, batteries were swapped over and then an easier solution in wind turbines (or using a portable generator) was quickly implemented. I also doubt FLA batteries would have had a long life on the Peak (due to depth of discharge issues, temperature, and available charge cycles), so replacements would have needed to be taken up from time to time.

I climbed the Peak for the first time in the eighties and the concrete pad area for the old radio installation was littered far and wide with plates from smashed batteries, so some batteries had clearly never made it back down (I think it was cleaned up when regular access to helicopters made it easier to do jobs like that).

Thanks Ian.

Winston Nickols provided some additional detail about the set up that may help explain why the batteries were replaced with the wind generator. The station on the mountain was more likely a powerful transmitter than a mobile unit.

So all these valves, running all day in receive mode, while the time clock allowed, was a major power drain.

Being all valve gear, the power consumption would be considerable by today’s standards. All the valve heaters (filaments) would have consumed a lot of power. So the batteries would have been under stress much of the time.

Winston was a good friend of Flip’s. Flip would frequently visit Winston at his workshop in Wivenhoe to discuss technical matters.

Great article Robert, amazing detail which fills some of the gaps in my memory from discussions with Dick and Flip.

I worked with Flip for 7yrs, the first few our offices were side by side in the old Ridgley shed. There was a constant stream of people into Flip’s workshop because he could fix anything. Beside the nursery there was a row of houses, Dick and Elise lived on the corner and the Wyker’s lived a couple of houses along, not far to walk to work.

Helen worked with a number of women, in our nursery for many years transplanting (pricking out) seedlings as well as other stuff. They also worked in the bare rooted nursery at times as well. I watched the Wyker children grow up and enter the workforce, they were a great family and your article is a great tribute to them.

When I first started at Ridgley in 1980 working for Dick, he had given me most of the background on Hellyer and VDL. He introduced me to the map cabinet where he kept a number of Henry Hellyer’s maps where he sometimes used them as working maps. I later discussed this with Bruce Hodgetts and suggested they belonged in a museum, which was subsequently done.

Thanks Robert. Great read.

So many of the names came back to me even though I never worked at AFH.

Our family moved to Somerset from Gormy in 1948 and my dad was a fitter at the Sawmill and mum was the Industrial Nurse at APPM from 1952 until her retirement in 1970.

My brother Jim also worked at APPM for a period. I did my Applied Science at Burnie Tech. from 1962 and spent the next 47 years at “the Pulp”. I met my wife in the lab and her dad Ellis Ashton worked on farms for AFH. Burnie was a small place in those days.

Regards

Peter Madden

I remember Ellis when he was working for AFH, and I was secretary in the office.

Hi Robert 👋, I remember Dick coming to the forestry house at Upper Natone when he was consulting with dad (Pat Crane Forestry Commissioner). Although I never climbed the peak, I did get to the top of Mt Housetop with dad when I was around 13. I carried a piece of quartz crystal off the top around with me on my travels for years after. Dad built and worked an alluvial tin mine on his block up there. We would seive for traces of Ruby in the slush. My Uncle Vern and my father built Crane’s Sawmill up in Surrey Hills and although 96 years old, my Uncle still has a sharp mind and sound memory bank of stories. He lives alone in sunny Queensland and would be happy for you to contact him. Kindest regards Deb Crane, WA

Hi Deb, I worked for AFH from 1985 until my first attempt at retirement in 2011. Just outside the eastern side of Surrey Hills, in the Loongnna area, is Cranes Rd. In the 2000s I was involved in purchasing the property this road led into for the company. Robert (our blogger) and Barry Graham, who has commented further up on this page, were also involved in the purchase process. It was then owned by a doctor based in Gawler, SA. I could see on the title that he had owned it for a long time. I had a number of phone calls with him during our negotiations and during one, I asked how he had come to own it. It turned out that he had purchased it during the 1970s when a lot of alternate lifestylers were buying cheap land in the Loongana area.

Cranes Road came off Maxfields Road near the Leven River and a small shack. It winds up a hill. After passing through regrowth forest I recall coming to a small house/shack on quite a large hilltop grassy plain. It still a very remote location. I suspect the sawmill was on or near that road.

I remember very well most of these names mentioned here. Flip installed one of the 2 way radios into the truck I drove doing low loader work, shifting the dozers around, especially at fire danger times and carting logs.

I actually shifted Flips house from Guildford to East Ridgley plus another two houses at the time. Ted Crisp was the main one that use to organise the moving of the houses and dozers, especially during fire season. Sometimes it was over the Christmas break.

I had a lot of happy times working on the low loader and carting logs for AFH in the Surrey Hills.