Fraser Island is a beautiful place. It is the world’s largest sand island and vegetated dune system. I had the opportunity to work on Fraser Island in the mid-1980s and have had several recreational visits to the island over the years. I still pinch myself these many years later on how fortunate I was to spend two weeks bush-bashing through the satinay (Syncarpia hillii)-brush box (Lophostemon confertus) forests while doing regeneration surveys. In all my 33 years working as a forester, these are one of the best forests I have experienced. Satinay is easily recognisable on Fraser Island for its tall, straight stem with heavily fissured bark. It is best seen at Pile Valley, near Central Station. Satinay grows to enormous sizes.

While the island is now a national park, it has a long and rich history of forestry management. By 1925, most of the island was set aside as state forest. Loggers overlooked the magnificent satinay trees as they were regarded as too soft for hardwood and too hard for softwood. Once forest operations moved from the softwoods to hardwoods, satinay trees began to be harvested. Originally satinay was known as Fraser Island turpentine to recognise its sibling in NSW and Qld.[1] It was, however, quickly condemned by timber-getters because planks cut from it were found to warp and shrink quickly, and sawmillers refused to handle it. This was because the tree is known to retain high moisture content when first felled. Consequently, “these alleged drones of the woodlands to make way for a new race of blackbutts” were ringbarked and left behind.[2] Unfortunately, “probably hundreds of thousands of super feet were destroyed and even burnt” because of its supposed uselessness.

A sort of silvicultural remorse drove the Forest Department to technological action. They decided to investigate how satinay could be used. It was soon discovered it was necessary to air-dry the wood in the shade, instead of in kilns. It seasoned down normally to an excellent timber with an astonishing variety of uses. At the Brisbane Annual Show in August 1929, the Forestry Department provided a realistic display of the “Valley of the Giants” – the large satinay trees found on Fraser Island. The display included furniture made of satinay to promote its appeal. The close texture of the satinay produced a beautiful lustre when polished. There was also a name change to disassociate it from Fraser Island turpentine and its reputation as an inferior timber. It was rebranded as satinay, named after the satine wood of the French Guiana which it resembles.

Suddenly, satinay became popular, finding its best use in high-class furniture, panelling, polished floorings, and fittings. Brisbane’s State Insurance building, built in the early 1930s, adjacent to Anzac Square, used 80,000 super feet of satinay for decorative flooring and other purposes.[3] Half the houses that were built in Brisbane in those times supported polished satinay flooring. It was also used, for instance, at the Brisbane abattoirs, because of its toughness in the runways for cattle.

Satinay quickly became the modern counterpart to its namesake, the brilliant satine from French Guiana, which found fame in some of the Louis XV and Louis XVI periods’ finest furniture.

Satinay’s main redeeming feature, however, is its resistance to marine borers. Combined with its straight form, it was ideal for marine piles. The shipworm (Teredo navalis) has been a problem ever since humans first went to sea.[4] It causes enormous damage to wooden ships. The best solution, which became standard during the 18thcentury, was to clad them in copper sheeting. It was an expensive solution for naval vessels and merchantmen, but every ship still needed a skilled ship’s carpenter to deal with the leaks and creaks.

Iron replaced wood by the late 19th century and ships were safe from teredo. However, the underwater furnishings of a maritime economy – jetties, wharves, piers, dry docks – continued to be built of wood, particularly in newly settled regions where wood was still plentiful.

A maritime economy based on wood used a lot of timber. Venice, for instance, consumed all the forests in its hinterland constructing its naval empire. The British Empire was also a maritime powerhouse. By the time James Cook first saw the Australian coastline in 1770, the British navy had consumed most of southern England’s forests and relied on timber from the Baltic and North America. Cook thought the tall trees of Australia, such as Norfolk Island’s pines (Araucaria heterophylla), that grow to a height of 65 metres, and other Araucarias would make ideal masts – though as it turns out, they were too brittle for that use.

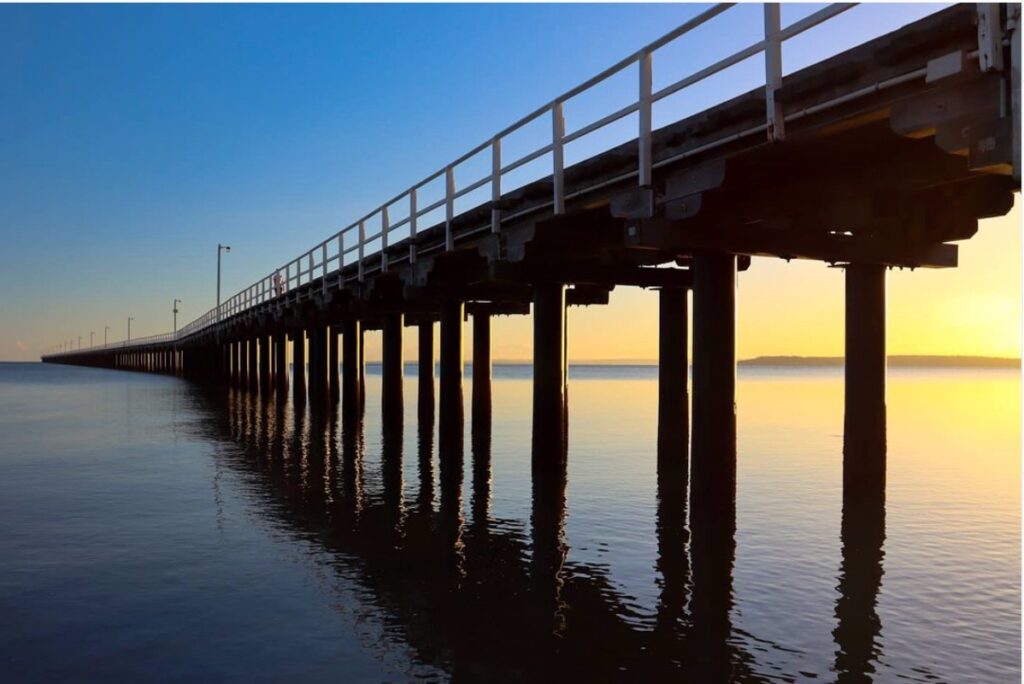

Enter satinay, and it quickly became very popular in the 1920s and 30s for marine piles when the original timbers were up for replacement. In the early to mid-1930s, the Suez Canal was re-lined with satinay logs – some 50,000 of them, according to Fraser Island sources.[5] Piles were also sent to rebuild the London docks in the 1930s. The piles for the Urangan pier at Hervey Bay were satinay and lasted 100 years.[6]

Another use for satinay was developed during WW2. A tobacco pipe factory was established in Sydney. It needed a replacement supply of timber caused by the sudden stoppage of French briar imports. CSIRO experimented with various timbers, and satinay proved to be the most promising.[7] Satinay was also a favourite for the butts of fishing rods and made good house stumps, fence posts and survey pegs.

Satinay developed its own romantic history. It was transformed from something of no use into one of the most famous of cabinet woods. Connoisseurs furnished their homes with period suites made from satinay. It also supplied thousands of tonnes of the required length for piles in saline waters; thousands of houses boasted polished satinay floors; and thousands of smokers lay their satinay pipes at the feet of Lady nicotine.

Satinay eventually took its place among the aristocrats of timbers around the world. Today its only use is to stand as a sentinel over a rich forestry past, admired by thousands of tourists who visit Fraser Island each year oblivious to its history, its unique features, and great uses across the world. That is because the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, with the imprimatur of the current government, is happy to remove all reference to forestry activities on the island and the part that these activities played in the economic and social development of south-east Queensland.

[1] Satinay is closely related to turpentine Syncapia glomulifera

[2] “Annual Arbor Day Article #4” Murrumbidgee Irrigator, Tuesday 27 July 1937, page 4. The reference to blackbutt refers to the main commercial hardwood species on Fraser Island – Eucalyptus pilularis

[3] “Satinay is a valuable Australian timber” Northern Star Wednesday, 13 September 1939, page 11

[4] It is commonly called the shipworm, though it is not a worm, but a bivalve mollusc. It lives very widely in salt-water environments, wherever there is wood to feed on. Teredois rapacious, and it seems to strike suddenly. It ate into the Dutch dyke system several times during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1917 it appeared in San Francisco, where it caused $15 million worth of damage to the harbour fixings. Although a salt-water animal, it can survive in brackish water, but the salinity level is important. One theory is that it may attack after a drought, when salinity rises following a drop in freshwater flows.

[5] “Turpentine piles for London” Daily Mercury, Mackay Wednesday 2 December 1931, page 12; “Trip to Fraser Island” The Telegraph, Tuesday 1 January 1935, page 7. On landing at the jetty at White Cliffs, reporter Jack Wilson saw “thousands of satinay piles [to be] shipped to Suez and Tilbury docks from this obscure little spot”

[6] The Urangan pier was built in 1917 to export sugar, coal and timber from the Wide Bay hinterland. It had an impressive length of 1124 metres. At one time, Urangan became the busiest coal port on the eastern seaboard, shipping more than 100,000 tonnes of coal per year. More than 1,000 x 22.5 m long Satinay logs were used to build the pier. The logs were hauled into the water by bullock teams, and towed by boat to the pile driver – a task so onerous that the workers could only manage to erect three piles per day. The pier head was dismantled in 1985 and today 880 metres remains. In 2013 the original satinay piles were replaced with steel piles in plastic sleeves and fitted with sacrificial anodes. So much for the use of natural and renewable materials which are no longer available because the public has allowed politicians to prevent any valuable use of Fraser Island’s unique forests, which today are condemned to gross mismanagement. For an example of this mismanagement see my post on the 2020 Fraser Island fire – https://www.robertonfray.com/2020/12/04/fraser-island-afire-from-stem-to-stern/

[7] “Fraser Island Satinay” Maryborough Chronicle and Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, Tuesday 3 December 1940, page 4

Great to see and read, needs to more factual reporting and holding these agencies to account. Go well Robert.

Robert,

A well-written succinct article. Well researched. John

Robert, well researched. One of the reasons for leaving large Satinay and other hardwoods, was that the weight of 3 metre (usual stud length at that time) logs, was too great for the railway cars of the time. The forest could not be regenerated with them still alive, so they were rungbarked. Many such trees were still standing during the 1980’s when I was there.

Regards Ray

Thanks Ray. I did have trouble trying to work out exactly why satinay was bypassed, without doing more intensive research through forestry records.

Robert,

I am afraid the erasure of Forestry Department history began long before the NPWS completed the assassination. The “ghosting” started back in the time when the FD was no longer a single entity, being absorbed and dismembered by other parts of Govt.

Great article.

Hi Robert

Well done again. Another very interesting article.

Your mention of teredo worms touches on a topic that has always fascinated me – the Royal Navy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (the age of Nelson and the heyday of sail). Resources like pitch and tar, hemp, baltic pine (for spars), saltpetre (gunpowder), copper (for cladding hulls to protect from teredo) and iron, and their ready availability for “Naval Stores” were critical to naval domination in that era. But none more so than English oak. The official march of the Royal Navy is still Heart of Oak (“Heart of oak are our ships, hearts of oak are our men”). Forests and sea power were inextricably linked! The Australia we have today depended on it!

About 4,000 mature oak trees (if clear-felled, this would be around 80 acres) were required to build just one ship-of-the-line that had an average life of twenty years and needed more oak during its life for refits and the repair of battle damage. At the high end, these trees had a growth rate of around 3 cubic metres per hectare per year and took around 150 years to reach the minimum 20″ diameter need for shipbuilding. In 1790 the navy had around 300 ships in its fleet (ca. 1,200,000 oak trees!) and that grew significantly in the early 1800s during the Napoleonic wars.

Its impact on the sustainability of oak forests of the UK is a story that has a very pertinent forest management message.

Safe travels, Ian

So true Ian. While there was some wastage of satiny until its valuable uses were recognised, can you imagine the pressure on its limited distribution, if its marine borer resistant properties were known by the British in the early nineteenth century?

I have a book (in storage) that provides a history of timber use in the pre-industrial era and how vital timber was in everyday life back then.

By the way, have you seen the Woolworths ads now bragging they are adopting sustainable practices by replacing plastic with cardboard? If only they, the governments and the public listened to foresters when we told them of the benefits of utilising a renewable resource instead of plastics, concrete, aluminium etc that have replaced timber products!

I haven’t seen the Woolworth’s advert (we get most of our video entertainment from streaming services these days – anything to avoid the news!) but can imagine what it’s pushing.

Recently Cripps Nubake in Tassie changed to cardboard bag closures for their (still) plastic bread bags, replacing the ca 1 cm x 1 cm plastic tag that has the date baked etc info on it. They then pushed hard their green credentials for the change in TV adverts. Why not a breathable wood-based cellulose bag as well – better for the bread and the consumer? Virtue signalling at its worst!

Brush box was looked upon with disfavour similar to satinay and for the same reason – difficulty and degrade in drying. Once this was resolved it also became a bread and butter species in the building trade, particularly for cladding and interior fitting. I now have a brush box kitchen that was made by Boral in the mid 1980s at a time when they were just putting the final touches to their laminating techniques with inch stock for bench tops; issues with glue lines was one of the things we worked on at WTFRD for Boral then.

I also have a box made from the last brush box tree to be cut on the island; log number 950, head log from the last tree felled in December 1991 in Cpt 21 Mackenzie by Graham Brady who worked for Andy Postan. These boxes were specially made as commemorative items; Nick Schulz the owner of barge ‘Island Trader’ kept this log back from unloading at Boral’s mill at the time.

I have yet to determine which mill actually cut up log 950 for Nick.

The boxes were made in 1993 and distributed by the Forest Protection Society, a timber industry group at the time.

Ivan Casperson turned some “broken columns” from the last Satinay log off the island, and Gave them out to forestry people who were involved at the time.

Speaking of boxes, during the 1974 Brisbane floods, Dave ( Gough or Greve ?) had a wooden box of timber samples under his flooded house. Some time later Dick Grimes was driving on the ocean beach of Fraser, as part of his job as hardwoods research, and spotted a named box sticking out of the sand, and eventually returned it to its owner.

A great and well researched article on an island where ‘a lack of ignorance’ by most involved in management (actually administration) is doing more harm than good to this unique wonder.

Pingback: What’s in a Name? These Days, Plenty of Woke – Quadrant Online