I recall reading an article by demographer Bernard Salt a few years ago about Australia being a continent divided by borders, lines, fences and boundaries. As I travelled around Australia I am reminded of his reference to ‘lines and boundaries’. Being a demographer, Salt referred to imaginary concepts based on social or physical elements, such as Sydney’s ‘Latte’ line, the ‘Barassi’ line, and Tasmania’s ‘Beer’ line.

The ‘Barassi’ Line is an imaginary line signifying the divide where Australian rules football is the most popular football code from those where rugby league and rugby union dominate. It is named after legendary Australian rules footballer and coach, Ron Barassi.

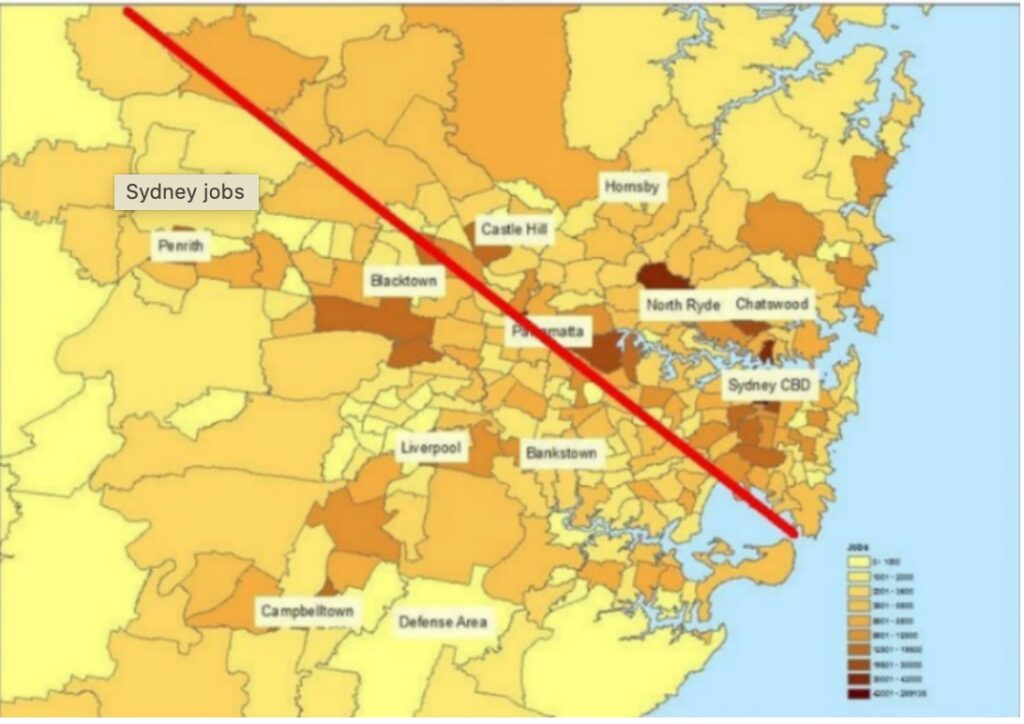

Sydney’s ‘Latte’ line could apply to any capital city in Australia. It divides the city on class and economic lines. It runs from the airport north-west through Parramatta, where white-collar workers are concentrated above the line. It is used as a way to show the socio-economic divide or class differences between Sydney’s western and eastern and northern suburbs.

Tasmania’s ‘beer’ line is probably less pronounced these days as the market is swamped by boutique offerings and consumers become more discerning. But in the 1990s and earlier, Tasmanians either drank Cascade if they lived in the southern half, or Boags if they lived in the northern half. This line was a microcosm of the distinct social north-south divide that has, and still defines Tasmania.

These imaginary lines are not unique to Australia. There are the ‘Wallace’ and ‘Maginot’ lines. The former was an imaginary line drawn by naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace that represented the difference between species found in Asia and Australia, particularly mammals. It is based on his observations during the nineteenth century and attempts to explain the different animals on either side of the line – marsupials in Australia versus tigers in Asia and honeyeaters versus cockatoos.

The ‘Maginot’ line is named after a French Minister of War who devised a plan to build a defensive barrier in northeast France along the border with Germany before WWII. While it is not an imaginary line, it was a hopeless barrier made from cheap material and could not resist attack, and it was never fortified. It acted as an imaginary line since the Germans eventually attacked and invaded France through Belgium.

There is one imaginary line that encompasses the world, and that is the Tropic of Capricorn. While it is not unique to Australia, it has resonance. We passed it in both Queensland and Western Australia. The Tropic of Capricorn is the southernmost latitude where the sun can shine directly overhead at noon once a year on the summer solstice on 22 December. It also represents the southern point of the tropical region. However, the line is constantly shifting because of a slight wobble in the Earth’s alignment with the sun.

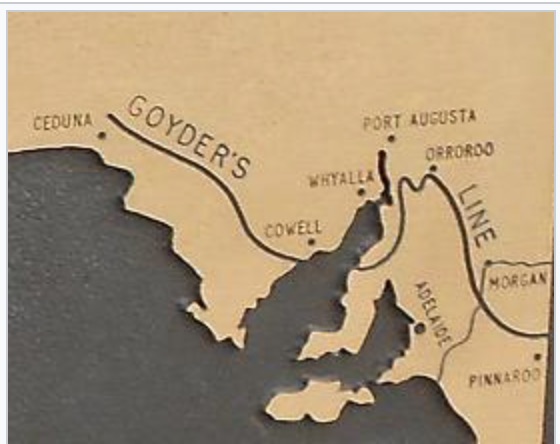

While travelling through South Australia, we came across the ‘Goyder’ line at a small town called Orroroo on our way to the Flinders Ranges. After the severe drought of 1864-65, the Commissioner of Crown Lands asked Surveyor-General George Woodroffe Goyder to examine the country north of Adelaide and draw a line on the map to show where the drought extended to the north and where the rainfall occurred to the south. Its purpose was to determine which pastoralists were entitled to a reduction in land rental.

Relying on variations in vegetation, Goyder plotted a jagged line on a map which became known as the ‘Goyder’ line. It is an imaginary line that essentially follows the saltbush across South Australia. It runs roughly east-west across the state, representing the 10-inch rainfall isohyet (250mm), although many rainfall zones are known to intersect the line.

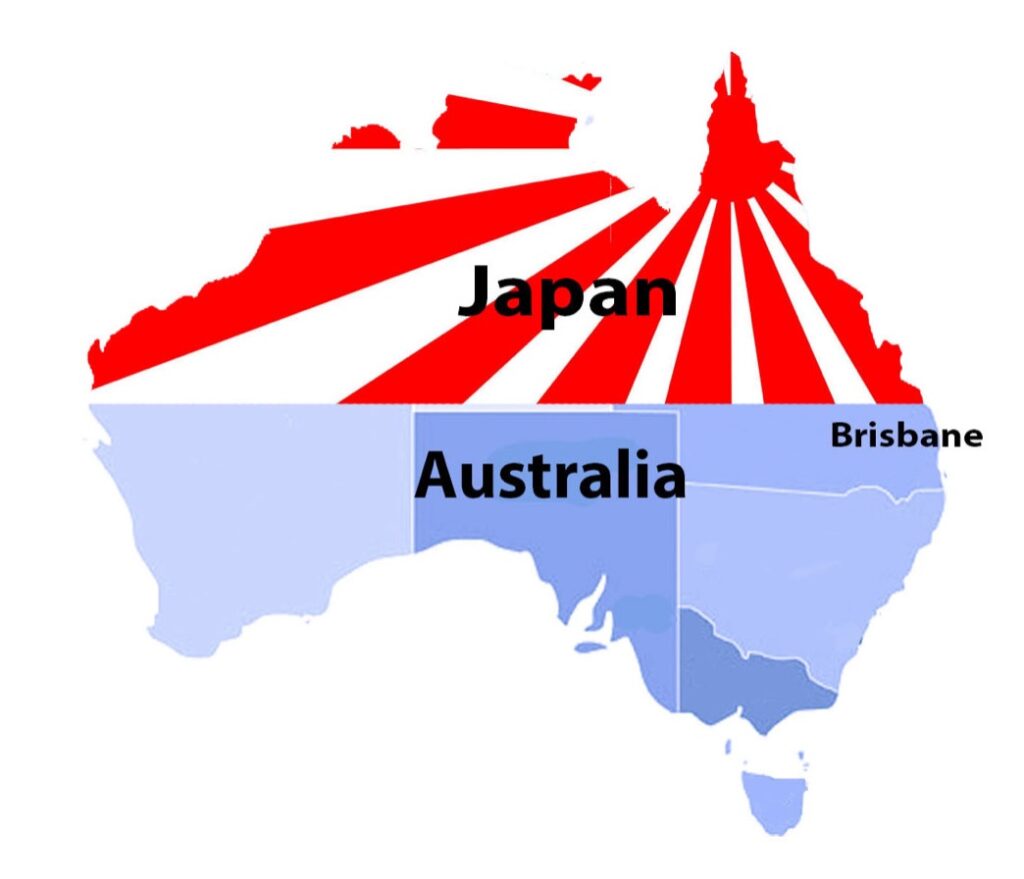

During World War II, when the Japanese threatened to invade Australia, there was an alleged plan to abandon the northern portion of Australia and focus on defending the populated south-east part of the country. It was known as the ‘Brisbane’ line. It appears that a defence proposal was drawn up by the army as a contingency plan but was never officially adopted by the government. The Minister for Labour and National Services, Edward Ward, accused the previous Menzies government of planning this strategy. However, a Royal Commission in 1943 dismissed the claims. It has remained a controversial defence proposal in Australia’s wartime history. It is believed that MacArthur mentioned the ‘Brisbane line’ strategy at an ‘off the record’ chat with the press at his headquarters in Brisbane.[1]

My book “Fires, Farms and Forests” describes the development of eucalypt plantations on Surrey Hills in north-west Tasmania. Surrey Hills is an unforgiving place in terms of cold and wet weather. Despite excellent basalt soils, it is a challenging place to establish fast-growing trees on a commercial basis. In the 1990s, the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) insisted that the company only invest in plantations on areas that could achieve an internal rate of return of about 10-12 per cent. A discounted cash flow analysis was carried out on a coupe-by-coupe basis, and Surrey Hills was particularly affected by this mandate. The southern half of Surrey Hills failed the financial hurdles, and a line, named after the said CFO, was established roughly in an east-west direction across Surrey Hills.[2]

‘Ley’ lines refer to straight alignments drawn between various historic structures and prominent landmarks. The idea was developed in early twentieth-century Europe, with ‘Ley’ line believers arguing that these alignments were recognised by ancient societies that deliberately erected structures along them. Some claim ‘Ley’ lines demarcate ‘earth energies’ and serve as guides for earth worship, UFOs and migratory behaviour. They are invisible and have the dubious title of ‘junk science’ or ‘pseudoscience’.

In the 1990s, ‘Ley’ lines became an issue in Tasmania. The then Forestry Commission scheduled several areas for harvesting in the Reedy Marsh area, not far from Deloraine in northern Tasmania. Environmental activists nominated these areas for the Register of the National Estate, stating a significant ‘Ley’ line existed in those forests to support their efforts to stop timber harvesting. The Australian Heritage Commission sought advice from many parties when assessing this nomination. The overwhelming opinion was that the original submission was fanciful and it was dismissed.[3]

There are physical lines in Australia and none are more spectacular than the Dingo Fence. It stretches over 5,614 kilometres from Queensland to South Australia. It is one of the longest structures in the world – three times as long as the Great Wall of China.

Are there other lines, real or imaginary, that are equally as significant?

[1] MacArthur was forced to give up the Philippines to the Japanese and retreated to Australia. He set up his base in Brisbane. This act alone added fuel to the fire that northern Australia above Brisbane would be sacrificed, if necessary, to defend the rest of the country.

[2] Under subsequent management, that financial hurdle was removed as the priority turned to find areas to plant to meet Managed Investment Schemes requirements.

[3] Thanks to colleague Andrew Wye for alerting me to this little-known history of using ‘Ley’ lines for a novel purpose.

Another great post Robert.

Here’s one to add to your catalogue of ‘lines’. My favourite is desire lines (aka a desire path). They are far from imaginary and once a landscape architect had pointed one out to me I couldn’t stop seeing them. They have been the source of scientific study.

A desire line is the shortcut taken by people when the constructed path is not direct. It can show itself as a trampled and worn strip in the lawn, sometimes reducing it to bare earth.

They have been cited as a metaphor for the wisdom of crowds. In some landscape projects the building of formal pathways is delayed until the architects can see the development of desire lines, ensuring that when the paths are built they are in the best location.

Cheers, Ian

Another great read Robert.

That part about the Line of Capricorn is very interesting, never realised the significance of these ‘lines’ before, thankyou.

My father served in WW2 in Army transport across the north of Australia and later in PNG. He didn’t like to talk much about his service but I do remember very distinctly his reaction to a television news report in the early 1990s (he died in 1995) in which the government denied that there had ever been a plan to withdraw from the northern part of Australia to south of the Brisbane Line.

He stood up from the dining table and yelled at the top of his voice “You bloody liars! I was up there transporting fuel to secret dumps so that they could get as much of the equipment and forces south in a hurry.” The government may not have “officially” approved it but it seems the Army was preparing for it.

By the way, nice to meet you at the Residency Museum today.

Hi Heather.

Likewise, I enjoyed our little chat today. The museum is wonderful and credit to all involved in the small town of York. Keep an eye out for my Travel blog on the sandalwood industry and a Forestry blog on the wheatbelt.

Re the Brisbane Line. I often wondered as I researched for my blog what the truth was. I have a healthy scepticism of government and their increasing invasion into our lives these days and I think there is more to the story as your father pointed out.

I have an upcoming blog on the sinking of HMAS Sydney, and I am appalled that there was no official inquiry immediately after the war. 635 families deserved better a lot of family and friends went to their grave without knowing details of their loved one’s fate. This has fostered a lot of conspiracy theories to speculate on why it sank.

Thankfully, we have a better idea of what actually happened now they have found the remains on the seabed.