Introduction

Early in my forestry career, I recall reading the fantastic story about building fire towers on top of karri trees in Western Australia. I got to see and climb one of them around the turn of last century when I had a brief visit to the south-west forests. I am in awe of the work involved at such dizzying heights unsupported by harnesses or scaffolding frames that are compulsory these days.

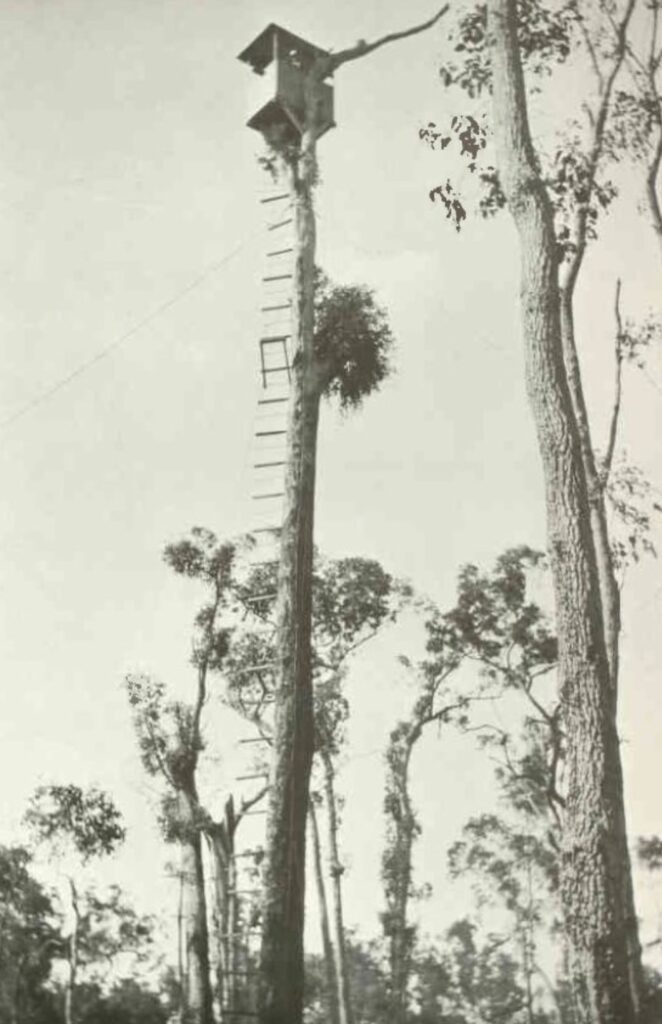

Nine tree lookouts were built in large karri trees between 1937 and 1952. While other places have used trees for lookouts, the tree-dependent fire surveillance system used in the karri forests was a unique and successful undertaking. The story behind building these fire towers is genuinely remarkable and involves the most daring and skilful work known in Australia’s forests. And there was very little engineering input into the construction of these unique towers.

Why were karri trees used as fire lookouts?

The karri forests in the lower part of south-west Western Australia cover an area of fewer than 200,000 hectares. The karri belt stretches from the mouth of the Blackwood River to Nannup and Manjimup in the north-west, and then south-east to the Frankland River down to Walpole and Denmark, incorporating Pemberton and Northcliffe. In addition, there are isolated pockets found in the southern corner of the state outside of the central Karri forest belt. The occurrence of karri trees is specific to the soil and depth of soil, so these isolated pockets are in a clearly defined line of where they occur and where they don’t.

Karri trees typically live for about 250 years with some individuals living to 350 years. They are at their best between 150-200 years yet approach their full height after only 75 years.

The construction of fire lookout towers in the tallest trees of Western Australia’s karri forest was a practical response to fire, one of the most severe threats to those forests. It was before the introduction of fixed-wing aerial surveillance. It was essential to detect and report fires early to fight them successfully. The usual practice was to build a wooden or steel tower at the top of a prominent location that afforded uninterrupted views of the landscape in all directions to allow for the early detection of smoke. However, the main karri forest belt on the Darling Range plateau is broadly level with no prominent topographical features to build a tower. On the other hand, the south-eastern karri forests, east of the Shannon River and down to Walpole, did have prominent mountains on which lookouts were constructed, such as Mount Frankland.

Karri is one of the largest hardwoods in the world, growing as tall as 80 metres. Combined with the large contiguous area, it just wasn’t feasible or economical to try and build huge fire towers to rise well above the tree canopy to provide a suitable vantage point. There had to be another way.

In the late 1920s, in the Manjimup-Pemberton area, a local axeman and tree faller from Latvia used to climb karri trees for fun and lop their crown at bush picnics. The Western Mail reported Doug Sproge’s daring exhibitions for an annual bush picnic crowd at Five Mile Brook, north-west of Pemberton. He spent the day before driving pegs into the trunk of a large tree every 30 inches to get to his destination below the first limb about 40 metres above the ground. He then drove longer pegs into the trunk as the base for a staging platform made of light boards. Then, the next day in front of his audience, he swung his axe for 40 minutes while standing on the platform to lop off the crown of the tree. Luckily Sproge had roped himself securely to the trunk as the strain was removed “the trunk of the tree whipped viciously…before slowly swinging to a trembling rest”. All present at this exhibition agreed that “Sproge was game”.

Young forester Don Stewart, based at Manjimup and later to become Conservator of Forests, witnessed Sproge’s dare-devil work. He reported to his senior colleagues that perhaps a lookout could be built in a tall tree on a low hill using the skills of Sproge and at a much lower cost. Stewart was already familiar with fire lookouts in trees. He had worked for a while in the Dryandra Forest, near Narrogin, were there was a lookout constructed in a powderbark tree. This tree, the Lol Grey Tree was discovered and rebuilt by foresters Jack Bradshaw and Roger Underwood in the mid-1980s.

Another forester, Jack Watson, a Gallipoli veteran, who later became the Superintendent at Kings Park, had already erected a lookout in a tuart tree near Ludlow. Senior staff seriously considered Stewart’s idea to build the tree lookouts in the taller karri trees nearly a decade later, in 1936. Watson held no fear in climbing trees. He first tested the idea of pegging and lopping on a large marri tree growing in a natural clearing near the Alco siding, about 16 kilometres north-west of Manjimup. The tree’s canopy was removed, along with surrounding trees, and a rough lookout tower was built and bolted to the exposed top of the tree. The result was an excellent view of the surrounding district.

Selecting the trees and building the towers

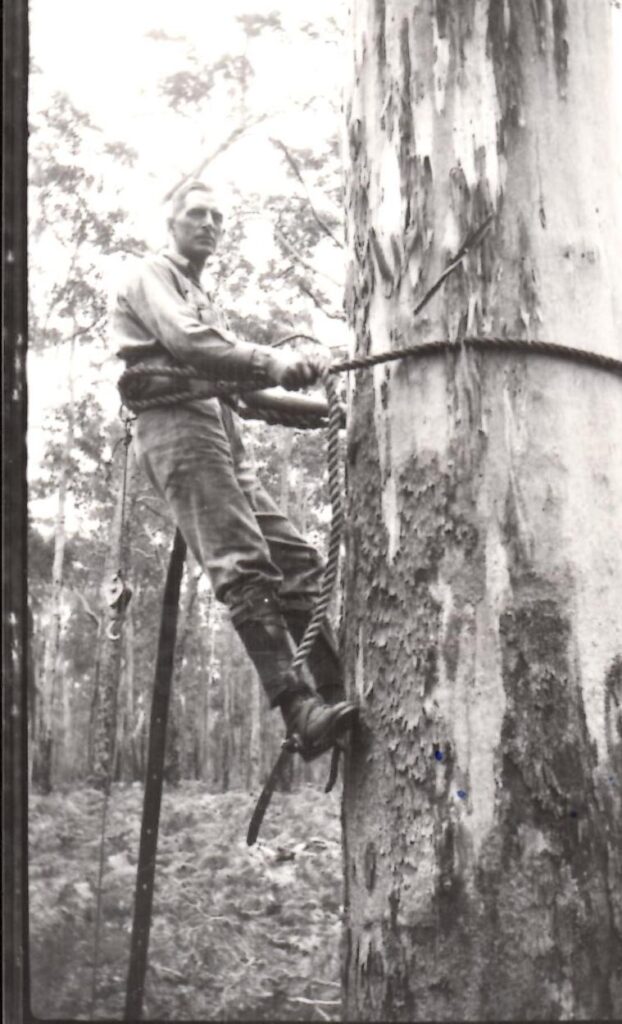

Watson and forest workman George Reynolds, a superb axeman also from Ludlow, were given the job of selecting karri lookout trees. The first task was to assess potential trees. It was not easy because it was difficult to know precisely what sort of view a tree provided until it was properly assessed within the canopy. Watson ended up climbing about 40 karri trees to determine their suitability as lookout trees. He used only a belt around the large stem and climbing boots and shimmied his body weight up the tall trees. It was gruelling work to reach up to 60 metres above the ground. Once near the top, he carried out a detailed survey of the vantage point, as well as the tree itself, to make sure the crown was sound and could support a log cabin.

Once a tree was selected, the next task was to peg the tree trunk as a ladder. Two-inch auger holes were bored into the solid wood of the trunk, and karri pegs were hammered into each hole. The pegs were two-inch by two-inch sawn pieces with a bevelled edge to insert into the auger hole. Each successive peg was slightly offset to produce a spiralling ladder up and around the tree.

The next task was to provide a path to the top of the tree through the branches that made up the canopy. Wielding an axe, Sproge or Reynolds would clamber through the canopy to the top of the tree. Once they reached the first limbs, they used their axe to chop a path to the top of the tree. It was topped off to provide a flat surface in the fork of cut branches to place the lookout cabin, all the while the treetop swayed in the wind. My vertiginous mind can’t fathom this sort of activity at such a precarious height, and my fingers trembled as I typed. All the tall trees around each tower tree were felled to provide a better view.

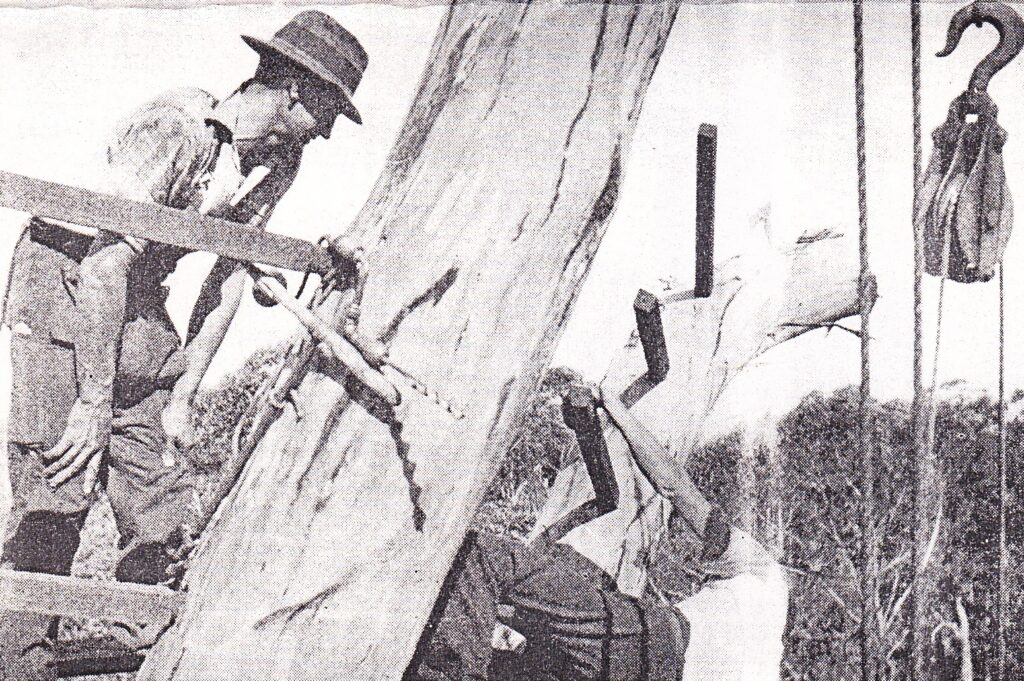

The design of each cabin varied depending on each tree. Bush carpenter Laurie Jones designed the cabin and carried out most of the building works, along with Len Nicol. First, they would prefabricate the cabin on the ground, and each piece was lifted into place using a derrick powered by a crab winch. Next, Jones and Reynolds would climb the tree and place the 8 x 6-foot bearers at the top to support the cabin. Finally, to bolt the bearers together, they sat in a ‘bosuns chair’ high above the ground, hand-drilling bolt holes into the bearers.

Each tower leg was winched up the tree and held in place by a small stay until the whaling plate and braces were fitted. Plate glass was then hauled up for the windows. Finally, the corrugated iron flat roof completed the job. Placing the last sheet was the most dangerous job. Jones had to swing his large body out over the side and slide through the window.

My vertigo continues unabated and goes into overdrive when I read about getting inside the Gardner No 2 tower cabin. The tower operator had to let go of the pegs, and while maintaining their balance, push open the trapdoor above them and heaved themself inside, totally exposed at the top of the tree bereft of any living limbs.

No matter how daring or dangerous the work was, they were well rewarded. Jones claimed he was paid £3.10.0 per day, including Saturdays, compared to his regular day job as a millwright of £7 per week.

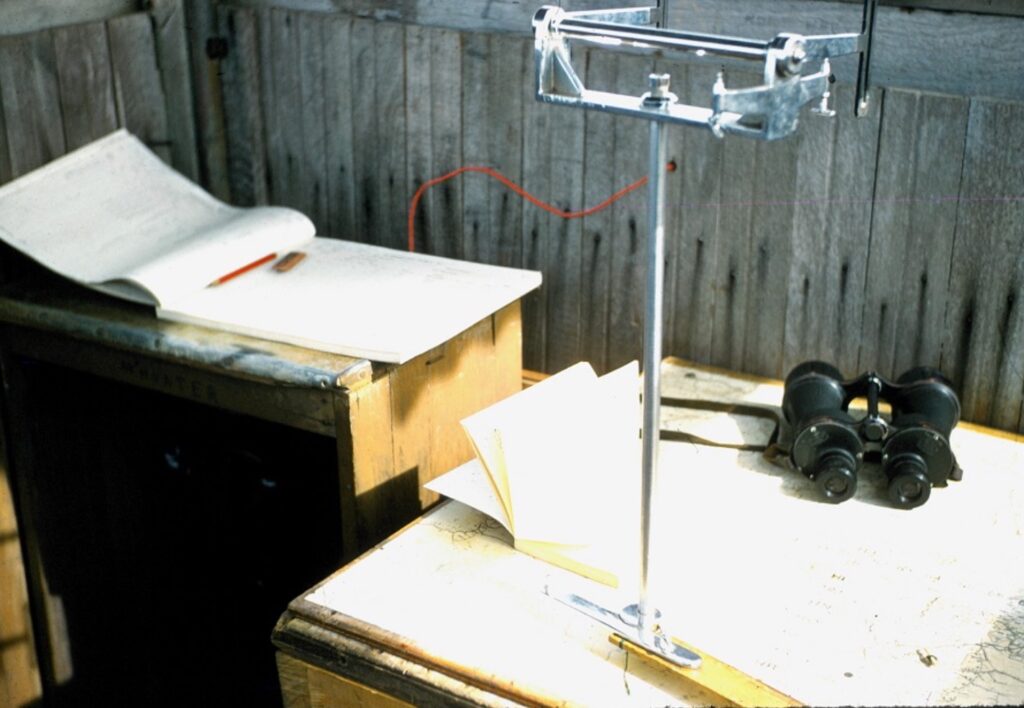

The cabin housed the telephone and later radio communication equipment. In the days before two-way radio or mobile phones, single telephone wires were strung between the trees and were used to communicate with fire-fighting crews and managers.

Towers were equipped with aids to help locate the location of fires. This consisted of a map table with maps, logbook, binoculars, scale rule, telephone or later radio, an alidade (a sighting device to determine directions and measuring angles), and a crude wind gauge – a short length of binder twine suspended from a rafter. The fire tower operator was taught to calibrate the wind strength by its deviation from the vertical. In addition, distances to prominent localities were usually provided to help the tower operator estimate the distance to the smoke. Most cabins were enclosed with glass windows, although the Gardner No. 2 tower was open to the weather. Unfortunately, it got pretty cold and windy over 60 metres above the ground.

A story on each tree tower

The karri tree fire towers were supplemented by ten lookout towers built on hills. The idea was to build several towers 80 to 100 kilometres apart to take cross bearings once smoke was detected to pinpoint where the fire was. Being located in living trees prone to ageing and effects of windstorms and fires, they didn’t last as long as the built towers. The Alco Tree managed to survive as a lookout for 26 years before being replaced by a 34-metre steel tower in 1962.

The first karri fire lookout tower, called the Big Tree, was constructed in 1937, just off Big Tree Road, about 15 kilometres south-west of Manjimup. There is a story stating that the pegs for this tree ran vertically up the trunk because they were easier to install that way. However, according to Jack Bradshaw, who has worked in the karri forests for 60 years, the pegs spiralled up the tree in the traditional manner. They may have been on a steeper grade than the later ones, and even vertical in short stretches making the climb much more difficult and dangerous. Unfortunately, the Big Tree didn’t last long after suffering from a bushfire. The crown section of the tree was severely burnt in a 1973 wildfire and sometime afterwards the top part broke off.

The Gardner No 1 tree was commissioned in 1938, and was located about 15 kilometres south-west of Pemberton. However, it only lasted two fire seasons after it was found to be unsafe. The lookout was finally abandoned in 1945. The tree continued to survive, but the crown fell in 1968 about seven metres below the lookout platform.

Sproge continued to merrily climb and lop trees leaning over bush railway lines or log landings. In 1939, he pegged and lopped the 120 feet (40 metres) Pemberton Tree, a relatively small fire lookout tree at the back of the Pemberton Forestry Office. Use of that tree lookout continued until 1970. Forestry staff still used the tree after that as an unmanned utility to provide an additional bearing when there was poor visibility from other lookouts. Unfortunately, the tree’s health declined, and after several attempts to save it, it was eventually felled.

The Diamond Tree lookout was built to replace the Big Tree and was used from 1941 to 1974. It is located on the South West Highway between Manjimup and Pemberton. At 51 metres, it was not so tall and wasn’t high enough to see over nearby hills, so a 30-foot tower and timber hut were added to the top of the tree. The tower was condemned in 1991, but after major structural work rebuilding the cabin and replacing the wooden pegs with steel ones, the Diamond Tree was used again in 1994, at a reduced height of 51 metres. A resting platform halfway up the trunk was also installed.

After 75 years of being climbed by fire watch personnel and the adventurous public, the tree was considered unsound, and for public safety was closed to climbing in 2019 and the lower pegs removed. Scars up the Diamond Tree show the earlier wooden peg line.

The Gardner No 2 lookout was built in 1942 to replace the No 1 tree and was located about a kilometre to the south-east of Gardner No 1 Tree. It was disconcerting to read that the tower operators climbing the tree had to step on the very outside of the pegs to get past old limb stubs. The weight of the person dipped the pegs appreciably. Those that sat in the cabin for hours on end used to say that you could hear the ants eating the deadwood on a calm day. In the last 30 metres of the climb, the tree had died back, and it was eventually declared unsafe around 1970 after an incident while being manned by a tower operator on duty. It got to the stage that one corner of the cabin was held up with a piece of 4 x 2 timber. The crown was destroyed by the windstorm associated with Cyclone Alby in 1978.

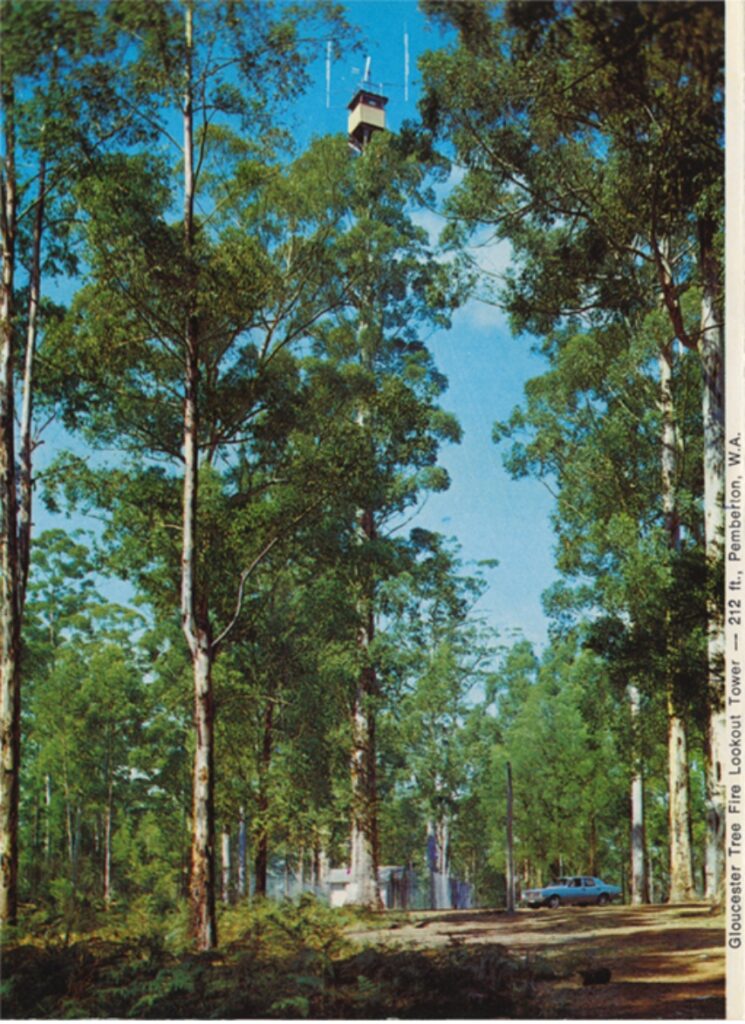

The Gloucester Tree was originally named East Tree but was changed to Gloucester after the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester visited Pemberton while the lookout was being built. They were entertained to a picnic lunch while watching the tree being pegged and lopped in preparation for the siting of the lookout. After showing a keen interest in the works, the Duke tried his hand at using the auger to bore a hole for the climbing pegs. After he remarked it wasn’t too hard, the axeman replied, “come off it, you’re not through the bloody sapwood yet”! The tree is located only two kilometres from the main street of Pemberton. At 61 metres tall, it was the highest tree fire lookout in the world. George Reynolds pegged the ladder and lopped branches to facilitate climbing the tree, and they built a wooden lookout cabin 58 metres above the ground. It was in continuous use until 1972, when aerial surveillance replaced a reliance on the fire towers. It has been periodically used as a backup in emergencies.

I read that Jack Watson holds the world record for the highest climb up a tree when he shimmied up the Gloucester tree in 1947. Although the record has probably been surpassed, most likely in California according to Jack Bradshaw. The climb was challenging, taking six hours due to the 7.3-metre circumference of the tree and the need to negotiate through limbs once he reached 40 metres.

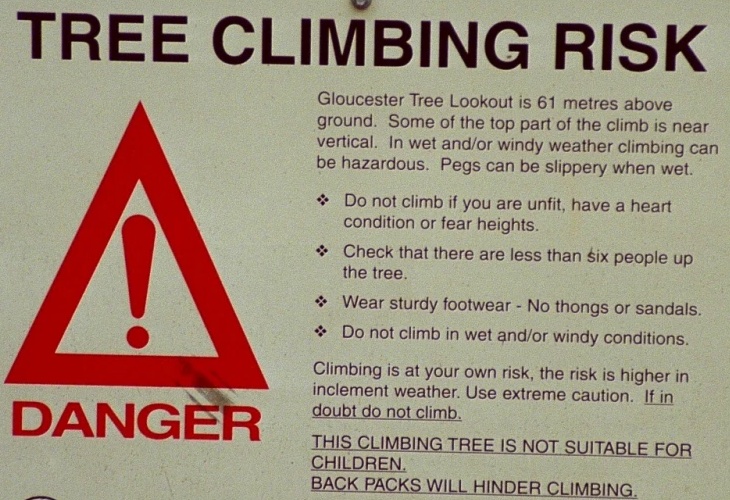

The Gloucester Tree is one of the trees the public can climb and now has a small metal viewing platform that replaced the lookout hut. It attracts about 130,000 visitors a year, with around 10,000 climbing the tree. Climbing takes you to dizzying, vertigo-inducing heights. One step after another on small pegs, all 153 of them.

The Boorara Tree is located near Northcliffe and was pegged and topped in 1952 by George Reynolds. The tree is 71 metres tall and one of very few old and mature forest trees remaining in the location. It was difficult to climb because the ladder reversed itself at one point, and climbers had to let go with both hands. The tower was no longer used after 1972, and the whole tree was condemned in 1978. The upper section of the tree with the hut was removed, as were the lower pegs to prevent access.

On the Deeside Coast Road, the Beard Tree was pegged and lopped in 1952. However, the tower was only used until 1968 after severe crown rot was detected on one major limb supporting the cabin, and the tree was condemned and felled in 1969. A new four-legged steel tower replaced it.

There is a karri tree with a platform and ladder built in 1988 from a Bicentennial Grant. It has never been an active fire lookout. It was pegged to celebrate Australia’s bicentenary and specifically built for tourists to climb. Once known as the Warren Tree, it is now called the David Evans Bicentennial Tree, in honour of local politician David Evans, a local member of Parliament for 31 years. It is located in Warren National Park and is one of two trees that tourists can still climb. It has 182 metal spikes spiralling around the trunk. The tree is now the tallest to climb, with the lookout platform located at 65 metres above the ground (200 feet), making it the highest treetop lookout in the world. Wire-netting has been added to enclose the spiral, which is a welcome safety feature.

No one has died climbing any of the karri lookout trees, including the public on the three available to them, although it has been reported two people died of a heart attack. One of those had their attack on top of the Gloucester Tree and had to be lowered down, with great difficulty, on a flying fox.

Some anecdotes

Retired forester Roger Underwood, who worked in the karri forests in the 1960s and early 1970s, has some great anecdotes about workers associated with these unique towers and the trees.

One involved John Meachem, the District Forestry Officer in 1952 when the Boorara Tree lookout was being completed. He climbed the tree to look at the installation of the cabin, and nearing the top, a peg he stepped on snapped off. He was left hanging 50 metres above the ground and managed to swing himself onto the peg below. He subsequently introduced a new safety measure – before any peg was installed, it had to be thoroughly tested by inserting in into a slightly oversized hole in a nearby tree, and a large man had to jump up and down on it.

Operating a fire tower all day can be pretty lonesome and boring if there are no fires. But there is an excellent story about courtship at the Boorara tree, whether true or not. Assistant Forester Jim Lovelock once drove up to the Boorara Tree and noticed a lady’s bicycle leaning against its trunk. He heard sounds of distant laughter from above, and the tree seemed to be jerking about a bit and swaying more than usual. Jim entered the hut below and rang the tower cabin on the bush phone. After a moment, the towerman answered breathlessly, and Jim said sternly, “this is to remind you that your job is to look for fire, not play with it!”

Barney White was up a tree with George Reynolds, who was about to start axing off the limbs. George was walking along a swaying branch near the top of the tree without any harness, rolling a smoke. He complained about it being a Saturday, as he wanted to get into Manjimup to put a bet on a horse he fancied.

Well-known Northcliffe settler and Irishman, Jim Laws, was manning the fire lookout in the Boorara Tree during a nearby bushfire, and the tree caught alight from embers on the main fire front. Jim stayed in the tree and continued providing valuable information to fire control while a forestry gang climbed the tree with water sprayers to douse the spot fires on the tree. It was Jim Laws who came up with a remarkable emergency plan. When asked once what he would do if the tree fell over, he said “I’d ride it down until it was six inches from the ground and then step off”.

After phones were installed in the towers, the operators used to talk to each other often to break the boredom on a long day without any fire activity or smoke sightings. Jack Bradshaw recalls attending a function for a retiring colleague. During the event a bloke came up to him and asked, “are you Jack Bradshaw?” When he responded yes, the guy replied, “I thought I recognised the voice.” It turns out he was on Boorara Tree when Jack was on Gardner. They chatted often to pass the time but had never met and it was at least ten years since they had spoken.

Another story was told to Roger Underwood by Les Carron, Professor from the ANU Forestry School. It was about the “Great Tree Climb” during the summer of 1948/49 organised by forestry students who were visiting Western Australian on a field trip. Starting at the Diamond Tree, it involved drinking a bottle of beer (in those days they were the “King Browns” larger than today’s stubbies) at the base of the tree and then climbing to the lookout cabin. The contestants were then driven to the Big Tree to do the same, followed by the Pemberton Tree, the Gloucester Tree, and finally, the Gardner Tree nearly in the dark. The winner was the one who climbed all the trees in the fastest time. While it was never repeated, it ranks as one of the most unique (and least enduring) sporting events ever held.

Finally, Roger Underwood and Jack Bradshaw created a dilemma when they decided to measure the Gloucester Tree using a newly acquired Swedish height-gauge in 1969. What they found was the height to the lookout tower was much shorter than previously thought at only 185 feet (56.4 metres). It was now significantly shorter than the Gardner Tree and now on par with the lowly Beard and Boorara Trees. They even returned to the tree and measured it using a tape and plumb bob to the ground after climbing the tree to double check. This was bad news as the Gloucester Tree was promoted in the literature of international tourism as the “world’s tallest fire lookout tree”.

Roger explains the dilemma in more detail:

“There was a sign at the foot of the tree. On the sign, and in the pamphlet put out by the Tourist Bureau, and on the postcards of the tree sold in every shop in town, and in the literature issued to visitors by the Forests Department, was the incontestable and incontrovertible fact that the Gloucester Tree fire lookout was “212 feet tall [64.6 metres], measured to the floor of the cabin”. It was a figure I had confidently quoted on numerous occasions, not the least to Lord Casey, the Governor-General of Australia, who had inspected the tree (from the ground) under my expert guidance earlier that year. Lord Casey had evinced mild interest in my explanation, as the tree had been named after one of his predecessors, the Duke of Gloucester, who had visited the tree in 1948 during its construction”.

In the end, Roger and Jack were both cunning as they published the new height at the time of the change-over from imperial to metric measure, “correctly assuming that few people would be able or willing to convert 212 feet into metres in order to double check our sign”.

Concluding remarks

As the era of using trees for fire lookouts declined with the ageing of the selected trees, aerial surveillance was introduced as their replacement. However, the efficacy of this costly regime was questioned and reassessed a decade later when new fire towers were built, and old ones manned again as they were more reliable and cost-effective than having aircraft continually circling the forest. The other factor was that planes could not fly in very high winds when the fire danger is exacerbated.

The karri lookout trees indeed represent an era foreign to those interested in the karri forests today, most of whom would rather see the forests remain in situ under benign neglect than support a timber industry and active management by professional foresters. This story is a tribute to the brave souls who climbed, pegged and topped these forest giants to provide an effective and cost-efficient means to protect the karri forests from the ravages of wildfires.

The following sources of information helped provide information for this story:

Dave Evans (1993) “Lookouts of the Karri Country”. CALM

Jenny Mills (1986) “The Timber People: a history of Bunnings Limited”. Bunnings Limited. Jenny interviewed Laurie Jones in 1978 and 1982.

Jack Watson (1940) “Selection of fire tower lookout sites in Western Australia by tree climbing”. Australian Forestry 5(2):116-18

Roger Underwood (2016) “Boorara Tree”. Northcliffe Karri Pigeon

Roger Underwood (1983) “Tree lookouts – a unique chapter in Western Australian history” Forest Focus 23

Roger Underwood (2003) “Tree climber: education of a forester”. York Gum Publishing

Roger Underwood (not sure) “The Great Karri tree climb”. Northcliffe Karri Pigeon

Nancy Bates (2014) “Heart stopper tree lopper: check Jack, Dick and karri”

Kevin Coate (2021) “Forestry Through the Fifties: a young officers journey with the Western Australian Forests Department”. Hesperian Press

Another well-told story Robert.

PS You dug really deep to find “vertiginous” in your dictionary!

One of many similar words hidden in the back of a writer’s mind waiting to be unleashed at the right opportunity!

I remember standing at the bottom of a tree in 1996. There was NO WAY that I would have even stepped onto the first peg!

Sorry, Robert, I must have misled you.

The photo at the beginning of this story is of Gloucester Tree, not Gardner No 2.

I know (or knew) Gardner Tree well, as I worked up it as lookoutman when I was a forestry student on summer vacation in 1960/61.

By the way, I revisited Gardner 2 Tree a few months ago. Although long abandoned, and the access road overgrown, I still managed to find it, and also the debris on the ground below which was originally the top of the tree and the cabin (it snapped off during Cyclone Alby). You can still see, and wonder at, the axe-work of Dick Sproge and George Reynolds.

I was sorry to see that the area has not been treated for bushfire protection for at least 50 years, so the tree is very vulnerable to a high-intensity fire. It is also surprising to me that the Department does not regard this as a heritage site. Gardner Tree is one of the icons of Western Australian forest history.

Jack Bradshaw and I also recently discovered the old Big Tree at Channybearup, still standing and festooned with pegs and wire, but without a cabin. According to a sign this tree is on some sort of heritage register, but apart from that, no effort has been made to protect it.

Roger Underwood.

Thanks Roger I have made the change.

Those men must have been extremely skilled. No way could I even get past a couple of steps.

As usual very interesting story Robert

Robert, good to have such a consolidated account of a key element of out forestry history and thanks also to Roger U for providing some historical images.

While appreciating the work/bravery/foolhardiness of building and operating such a system, being an east coast whimp I prefer fire towers of more conventional construction.

There are many stories around these too waiting for your pen.

Cheers

Ian B.

Robert … a fabulous story.

Well researched and a great record of a significant era in WA’s native forest management history. The skill and bravery of those who constructed and worked in these towers is undeniable.

I visited WA in the pre-MIS era, when the then WA forestry department (part of CALM) was promoting the expansion of blue gum plantations to lower water tables…we visited the Gloucester tree.

We were able to climb part way up but for some reason a full climb wasn’t achieved. I think it was closed for maintenance…that’s my story anyway and I’ll stick to it!

Now there is a trifecta of yarners, viz. Underwood, Bradshaw, Onfray.

8 to 1 on as favourites.

Always winners.

A great read, well done. I would just like to point out a few things if I may:

The Pemberton axe-man’s name was Dick Sproge, not Doug

The Alco tree tower was replaced with a timber tower, not a steel one

The crown of Gardner 1 tree fell in 1966 according to Dave Evans’s book – Page 44

My colleague Max is proud to claim that Gardner 2 is almost direct South of Gardner 1 and closer to 600m apart, he’s visited both sites Nov 2020.

Regarding the Boorara Tree and the ladder that ‘reversed itself’, we’ve never heard that characteristic mentioned before, so we found that interesting.

Regards Andre

Well spotted Andre!

For completeness, mention should also be made of the tree lookout which was at Somerville Plantation (also referred to as Applecross Plantation) in Perth’s southern suburbs. My tree knowledge is not of a standard to positively identify it from a photo, but it could possibly have been a tuart.

Situated north-west of today’s South Street/North Lake Road intersection in Kardinya, the reason it appears to have been felled whilst still serviceable was that it was very close to the old South Street alignment (an old map plan shows it right next to the single-lane road of the time, with forestry buildings arranged in a semi-circle around it).

That road is now a multi-lane thoroughfare, and the tree would have fallen victim to the road widening carried out in the 60s. It was replaced by a 3-legged 70ft wooden tower erected short distance to the north, and that too is now no longer extant (as is the plantation – all housing now, with only some scattered pines hinting at the area’s former life).

The information I have is that it was pegged around 1950, and was about 40ft tall. Back in the old days, Perth youngsters didn’t have to travel all the way to Pemberton for the thrill of a climb!

Max

A great article Robert, which I have just come across.

For the sake of accuracy, the height to the floor of the upper floor on the Warren Bicentennial (Dave Evans) Tree is 68.3.m above ground level. As the officer who jointly selected the tree, climbed it to validate its structural integrity, then supervised its construction, that measurement was one of the last tasks I undertook on completion of the project.

During my career as Regional Fire Officer, part of my duties involved regular inspections and repairs of fire lookouts in the Southern Forest Region, and elsewhere at times.

I supervised major restoration work on the Gloucester Tree, and the Diamond Tree. The latter was the greatest challenge as the upper section of the crown limbs were significantly affected by wood rot. How the upper tower at the top of the tree hadn’t fallen off, I don’t know.

Lifting the 6 m tower, and the cabin off the limbs and to the ground for refurbishing, was a great challenge. The upper limbs then had to be removed, and new jarrah beams to form the base for the tower bolted to the limbs before the tower was lifted back into position.

Hopefully, with regular inspections and maintenance, these lookout trees will be available for climbing for many years to come.

John Evans.

Thanks John for the clarification.

Wow, thanks for your first hand account of the refurbishment of both the Gloucester and Diamond Trees.

I am in awe of the work of all the foresters associated with these trees over the years. A truly remarkable part of Australian forestry history.

Hi Robert, I just found this page. Great read.

My wife and I are visiting Pemberton as we try to get down here every couple of years.

I was born in Pemberton as my parents built what was known as the Avalon Guest House situated at the top of town, one mile from the Gloucester tree.

I was amused to see on the warning sign in the photo above that it was not safe for children to climb the tree.

In 1962, at the age of six, myself and several other children ventured out to the tree and proceeded to climb to the lookout hut. We knocked on the trapdoor in the floor to be let in. The look on the fire watchers face when he saw us was of utter shock but he did let us in and proceeded to give us our certificate stating that with courage and decorum ……….. had climbed the 212 ft Gloucester tree.

Upon returning home, I informed my mother of my feat. She didn’t believe me until I proudly showed her my certificate. I have climbed it many times since.

Regards Chris Roissetter

Great story Chris. Thanks for sharing. I hope you enjoy the other blogs.

Great story Robert. It had special meaning for me as on a very wet day many years ago on a visit to Pemberton, my friend and I both took photos of each other as though we were climbing the Gloucester tree. We didn’t complete it of course, no way. I can remember us both commentating, how brave some people must have been to climb up as it looked impossible to us!