“Surely there can be no greater cathedral as forests such as those of the karri.” Vincent Serventy

“If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools” Rudyard Kipling

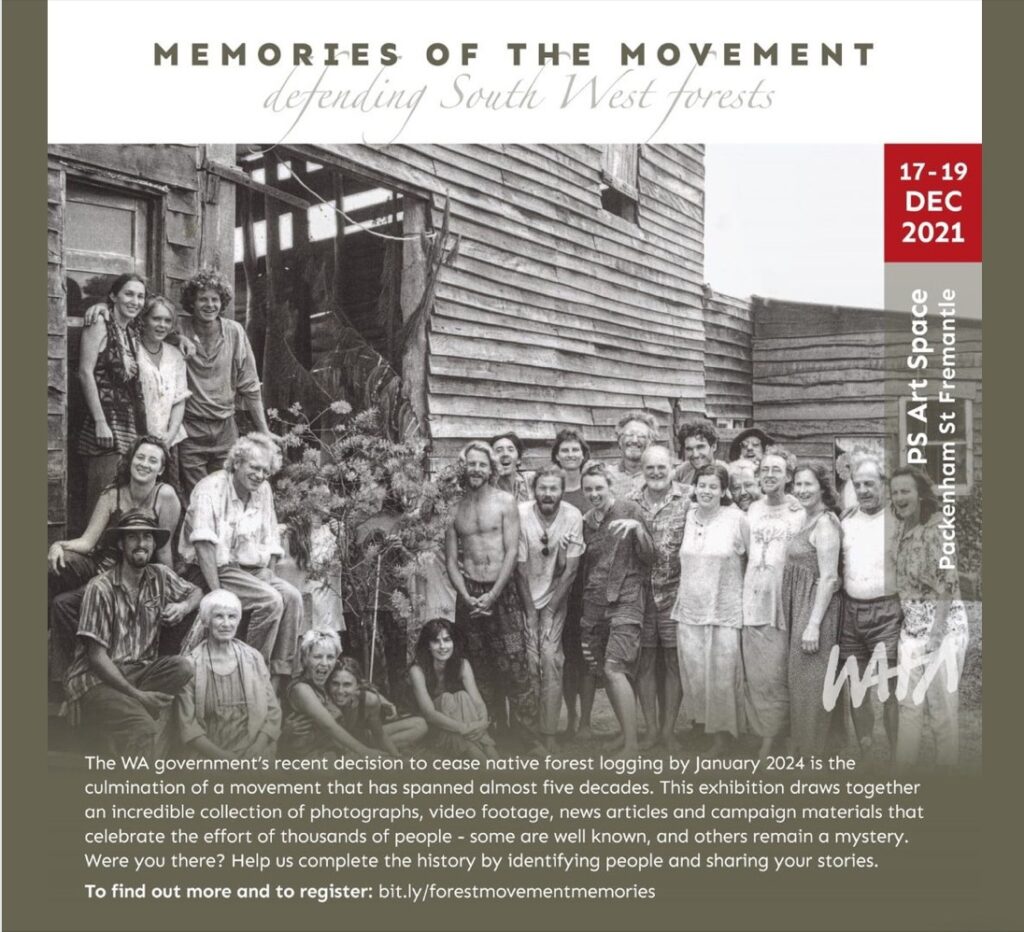

The “defenders of the South West forests” are celebrating the recent announcement by the Western Australian Premier to cease native forest logging by January 2024. These activists claim it is a culmination of a movement that tried to protect the “precious” native forests spanning five decades. An exhibition of photographs, video footage, news articles and campaign materials was held in Fremantle last December to celebrate the “effort of thousands of people” in their pursuit of a “heartfelt and courageous forest defence”.

The WA Forest Alliance hosted the exhibition. This group was formed in 1990 as an umbrella body for the many community environmental organisations, mainly based in Perth. They advocate for no logging, thinning and clearing of the public native forests and, more recently, are opposed to any prescribed burning. The exhibition played out like a classic David versus Goliath battle where the righteous prevailed over the rapacious forest industries and foresters.

Recently, the ABC’s Radio National reporter, Fiona Pepper, wrote a polemical story about the forest activists, putting former Western Australian Greens’ MP Giz Watson and full-time activist Beth Shultz on very high pedestals. According to Dr Shultz, the forests of the south-west have been radically depleted and irreversibly impacted by logging. However, she has never been able to offer any rigorous scientific evidence to back her claims.

Rather than using science, the green campaign to stop logging in Western Australia has resorted to eco-terrorism. For example, in July 1976, two men were arrested and jailed for bombing the Bunbury wood chip terminal. They held the security guard at gunpoint and tied him up in his car before attempting to destroy the terminal using two bombs. While Shultz and the WA Forest Alliance distanced themselves from this heinous crime, some members of Western Australia’s forest protest groups still showed spontaneous expressions of sympathy in support of the bomber’s actions. Shultz and the WA Forest Alliance had no problem subsequently organising and supporting what they called “non-violent” direct action using road blocks, tree sits and forest blockades.

As one who has personally experienced forest blockades, they are anything but peaceful, non-violent and righteous (see my account of a blockade in the upper Bellinger River Valley in the early 1990s where protesters physically accosted me and pelted me with balloons filled with urine. A koala, injured on the Pacific Highway some 60 kilometres from the forest blockade, was cruelly paraded in front of the media at the protest site for photo opportunities until it died from its wounds).

The success of the forest protestors can be attributed to their ability to gain broad public support through targeted protest activity, and the consequent pressure on the state government to change forest policies in favour of preservation. The media and city folk fawn over the WA Forest Alliance and its members, using their high public profile to build them up as the forest saviours.

But are they? What contribution do they bring to managing the complex issues associated with a vast forest estate in the south-west of Western Australia to meet several competing needs, other than a simplistic philosophy of letting nature take its course?

In the beginning

The first conservation battles over the forests started well before the city-centric activists became interested in the jarrah and karri forests. In the 1890s, foresters recognised the threats of alienating forested land for agricultural expansion. They fought a dominant agricultural bureaucracy focused on clearing and taming the land for farming. As John Ednie Brown, the first Forest Conservator of the Department of Works and Forests wrote, “the best crop for jarrah soil is jarrah trees. The wastefulness of trying to grow grass for possible short-term pastoral needs is suicidal and incomprehensible in the extreme”.

Foresters also saw a need to regulate the timber harvesting of sawmillers who could cut what they wanted and how much without any consideration given to regenerating the forest for the future. They also recognised the intrinsic value of forests for catchment protection, recreation and nature conservation.

The administration of the state’s forests began with the appointment of a professional forester as Conservator in 1916. Charles Edward Lane-Poole introduced the fundamental principles of forest management, ensuring practices to regenerate the forest after harvesting and protect them from fires. He drafted legislation that established a Forests Department, formalised the dedication of State forests as a permanent forest resource and introduced controls over timber extraction through permits. In addition, a significant portion of the royalties from harvesting was set aside for reforestation and forest improvement work instead of going to consolidated revenue.

This new piece of legislation, called the Forests Act, 1918, was extremely controversial at the time. Despite the fact that many of its provisions had been enacted in other states, “the notion that forests should be preserved as a resource – in this case, a utilitarian resource for the timber industry – was a radical one that received a lot of opposition in the forests areas”. The commitment of the pioneer foresters prevailed over this criticism and they ensured forests were not cleared, that knowledge of eucalypt forest dynamics was gained, and appropriate forest silviculture was provided to produce regeneration and a sustainable supply of timber.

Almost all of the remaining best quality jarrah and karri stands were dedicated as State forests. The south-west region of the state would be a much different place without the forests we see today. In recent times, and despite a history of forest utilisation, they have been the basis for transferring large portions to a national park or other conservation reserves because of their high conservation values.

The Hills forest

The jarrah forests have a long and proud history of timber utilisation. However, there were inappropriate management practices in some areas and none more so than the forests in the Helena River Valley. This forest supplied firewood for the No 1 and No 2 pumps for the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme, built to pump water through a 560-kilometre pipeline inland to the eastern goldfields. These pumps ran on steam fuelled by the plentiful supply of free timber nearby.

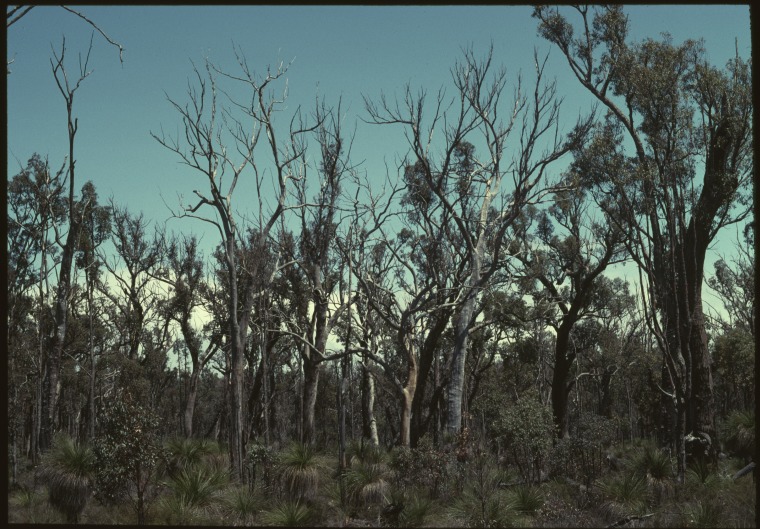

The Public Works Department managed the forested catchment as a water reserve. However, their engineers became concerned when the new reservoir took so long to fill up. They blamed the trees in the surrounding forests. So, they decided the best solution was to remove the forest. Beginning in 1905, small trees were cut down, and the larger ones ringbarked over five years to increase the water run-off in the catchment.

Over 5,000 hectares were treated this way. The folly of their decision was soon apparent. Water became saline, and the pipeline suffered from “atherosclerosis” due to salt build-up inside the pipe. Instead of taking a few days to pump the water to Kalgoorlie, it now took weeks. As retired forester and historian Roger Underwood says, this decision “should appear in textbooks as one of the most foolish ever perpetrated by a West Australian government agency”. Fortunately, the ring barking stopped, and the forest was transferred to State forest under the control of the Forests Department and foresters took over the management of the catchment forest.

They introduced proper forest management, including appropriate silvicultural treatment and fire protection, which minimised the threat of wildfires and treatments to encourage regeneration of the trees. They also regulated the cutting of firewood for the pumps. The supply of firewood was a big operation with over 18,000 tonnes required each year. Sixty woodcutters were brought under control using one of the country’s first-ever forest management plans that the Forests Department prepared in the early 1920s. Under this plan, the forest was managed primarily for water catchment purposes, and firewood operations were tightly controlled, with the ringbarked and cut-over areas regenerated and later thinned. Until the mid-1950s, the forest continued to supply firewood to the steam-driven pumps until they were replaced by one new electric pump.

This same forest also supplied millions of tonnes of firewood over half a century up to the 1950s for the many businesses in Perth, such as bakeries, foundries, hotels, schools, hospitals, factories, and households.

Professional foresters ensured the forest resource was managed correctly for its intended uses on a sustainable basis. The biggest lesson is that you don’t need to lock up the forests to renew and protect them.

Today, this forest is now admired by thousands of recreational visitors from the city without knowing its past utilisation history and the role foresters played in ensuring the resource was adequately utilised. Through their management, the forest recovered from the initial ringbarking treatment.

The karri forests

When Baron von Mueller, an eminent botanist and explorer, visited the karri forests in 1877, he wrote these somewhat prophetic words in his diary: “But as nowhere, not even in the most extensive woodlands can the supply of timber from natural forests be considered inexhaustible, a rational far-seeing provision for the maintenance (if not enrichment) of its forest-treasures is needful for Western Australia, however indiminishable these may appear to be at present.”

Karri is a unique tree found only in the south-west region of Western Australia. It is a thin-barked fire-sensitive species that can grow as tall as 80 metres. The best stands of karri admired by both foresters and the WA Forest Alliance are the even-aged stands that have been initiated from intense wildfires that killed the previous crop, opened fruit capsules for seed to regenerate in a clean ash bed of mineral soil.

Warren National Park was first reserved in 1910. It is lauded as an iconic “old growth” forest. Unfortunately, the green activists and politicians don’t understand that it is mainly an even-aged stand over 260 years old and nearing its eventual demise, with many trees already showing a significant crown decline. Over the next few decades, the trees will gradually die, and unless a major disturbance such as a clearfell logging operation or a large wildfire occurs, it could eventually disappear.

This is in stark contrast to a 150-hectare section of the park decimated by a wildfire in 1956. It is now a magnificent new karri forest and an example of the ability of karri to recover from disturbance. Another national park example is the iconic Boranup Forest. It originated after being clearfelled for sawlogs about 130 years ago. There is also the stand of karri on State forest near Pemberton called the “Hundred Year Forest” that was cleared for a wheat farm nearly 150 years ago.

All these karri stands have benefited from active management, particularly the forest fuels. However, the WA Forest Alliance advocates a “hands-off nothing will change” management approach, particularly in the older even-aged stands. So the question for these self-styled forest saviours is what is the future of these mature stands of karri with no plans for renewal? Why do they think their current condition and biodiversity will remain perpetually unchanged?

Despite being much maligned over their management of the karri native forests, foresters understand their very essence to ensure they continue in perpetuity. But, unfortunately, I don’t think the amateur forest saviours clearly understand this concept based on their mentality of “save the old-growth forests and do nothing” approach.

A world-class fire management system

Australian foresters developed one of the world’s most effective bushfire management systems that prevented disastrous fires in the south-west for nearly 40 years. But it only came about after some hard lessons were learnt from a fire disaster that foresters didn’t anticipate.

One of the tenants of successful management is the importance of humility, learning from mistakes and acknowledging when practices need to change. That has applied to the relatively new profession of forest management in Australia. Early forest management was based on looking after forests in foreign lands that were different from Australia’s unique eucalypt forests and climate.

The first professional foresters in Western Australia were trained in Europe and brought a forestry philosophy developed over a couple of centuries that was inappropriate for Australian conditions. For example, fire was regarded as an enemy in Europe, and the initial fire policy within the Forests Department was to broadly exclude fire in State forests.

They focused on dividing the forest into manageable blocks laid out by a system of tracks around the perimeter of each block. A buffer strip of about 100 metres was burnt every 3-5 years, with the interior of the forest block kept unburnt. However, from a practical point of view, it became impossible to carry out burns in light fuel immediately against fuels that were allowed to build up.

After WWII, the first Australian professionally trained forester was appointed Conservator of Forests. Allan Cuthbert Harris believed regular prescribed burns were needed to minimise damage and help fight wildfires. The change was gradual as the foresters were cautious of damaging regenerating trees. Burning was very patchy and removed little of the accumulated forest litter.

It all came to a head in the disastrous 1960-61 fire season where over 350,000 hectares of forests were severely burnt in several wildfires, including the Dwellingup fire, which wiped out the town. Thankfully, no lives were lost.

The response was pretty dramatic. More resources were dedicated to broadscale fuel reduction burning with a greater priority during periods of suitable weather. Fire behaviour research was given prominence. A specialised fire management unit was established within the Forests Department to focus on carrying out large burns, access was improved, and planning and monitoring procedures were introduced. The fire detection system was enhanced, equipment was upgraded, and a more accurate method of recording burns was initiated.

One of the more prominent findings of the failures associated with the 1960-61 fire season was a realisation that the damage to the forest caused by fires was in direct proportion to the fuel loads. This led to planned burns based on fuel accumulation rates, which minimised fuel age to five years in jarrah and seven years in karri forests. A study showed that the karri forest would accumulate up to 60 tonnes of flammable litter per hectare after 60 years if left unburnt. Putting that in context, controlling forest fires is difficult when fuel levels are greater than eight tonnes per hectare.

The Forests Department, led by George Peet, carried out measurements in more than 400 experimental fires. Fire intensity was quantified under differing variables associated with fuel and weather. As a result, a fully operational burning program was developed in less than five years. The West Australian foresters, in a joint program with CSIRO, were the first to pioneer aerial burning in Australia in the mid-1960s to help them achieve broad scale burning targets across the south-west forests that was safe, effective and met clear goals to minimise damaging wildfires under severe fire weather conditions.

It is a credit to the forestry profession that foresters avoided large-scale wildfires in the south-west for over 40 years due to their extensive broad scale burning program. Since the mid-1990s, particularly in south-eastern Australia, there has been a gradual demise of professional forest management and a greater priority given to biodiversity protection at the expense of fire management. Bushfire policy is now driven by city-based environmental activists. The last 67 years of data from Western Australia leaves no doubt that when the area of prescribed burning is reduced, there are more uncontrolled wildfires.

The government, environmentalists and some academics argue that current forest managers have better on-ground equipment and large air tankers to suppress wildfires. But that is the problem with modern-day fire-fighting – there is too much emphasis on fire suppression at the expense of utilising fire for fuel management. And as we have seen in the eastern states this century, severe wildfires are increasing in frequency at the expense of ignoring fuel management outside the fire season.

Phytophthora dieback

In the early 1920s, a forester first noticed jarrah trees were dying alongside understorey species in a forest about 35 kilometres south-east of Perth. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1940s that the disorder was called ‘jarrah dieback’ as it affected the commercially important jarrah, while marri was unaffected. At this time, the timber industry changed from rail to road transport, and machines were used to build roads and harvest trees.

Initially, it was thought that the problem was some form of crown deterioration. Individual groups of dying trees were small, but there were numerous patches. They were found on previously logged sites, usually in poorer areas but in similar topographical positions on saddles, gully heads, and upper sections of drainage lines.

The issue was considered severe enough to establish a joint State and Commonwealth field research station at Dwellingup in 1948 that focused interest and several studies on the problem. However, it wasn’t until the hard work of research forester Frank Podger led to the discovery of an association between jarrah deaths and infection with the introduced soil and water-borne plant pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi. Podger had earlier been seconded to investigate the deaths of Pinus radiata shelterbelt on the Swan Plain. He knew about similar mortalities in shelterbelts in New Zealand and a leaf disease in P. echinata in the USA. Those problems were associated with Phytophthora species, soil-borne pathogens with a wide host range that attacked fine roots.

Podger organised a plant pathologist to assist him in his investigations. He also managed to get the services of a Phytophthora specialist from the USA who was on a sabbatical in Australia. By identifying this pathogen as the cause in the dieback of jarrah, Podger stated it would be spread by the movement of infested soil and modifications to logging practice and road construction would be required to minimise the disturbance of the soil. The first sign P. cinnamomi has arrived in an area of jarrah forest is the rapid death, usually in autumn, of most understorey plants. Without human assistance, it was observed that the fungus spread slowly uphill, and downhill spread could be more rapid as water flowing over and through the soil carried zoospores of the fungus with it.

It was a pity the P. cinnamomi wasn’t identified as a cause of jarrah dieback earlier, particularly before the introduction of heavy machinery, as much less of the forest would have been diseased. To their credit though, the Forests Department quickly introduced forest hygiene measures to stop the artificial spread. Restrictions on the movement of machinery from diseased to healthy areas were introduced, as well as thorough washing of machinery when they had to be moved.

If the WA Forest Alliance and their supporters in the bureaucracy had a say in solving the problem, their simplistic response would have been to shut down the valuable jarrah logging industry while it was in its prime. Luckily, we had pragmatic foresters who could assess the situation and develop strategies to deal with the problem and keep an important industry alive. The Forests Department prioritised the issue and set up new research facilities in Perth, Dwellingup and Manjimup. Six research officers mapped the problem, calculated the rate of spread, screened alternative timber species, evaluated environmental factors, and investigated control measures. The Department also sponsored research programs on P. cinnamomi at the University of Western Australia and the Australian National University in Canberra.

Foresters responded to this emergency by developing a range of novel and innovative management practices that identified infested areas, risks and minimised spread. These practices have been so successful they are implemented in national parks, other reserves and mining operations. They have also been adopted in other parts of Australia. As a result, foresters can be proud of their achievements in addressing a very serious threat to the jarrah forests.

Western Shield

One of the world’s most extensive campaigns against feral predators was initiated in 1996 to save threatened native mammals and return them to areas where they once thrived. Called Western Shield, it had a budget of $1 million each year. It originally started on a smaller scale called ‘Operation Foxglove’.

A trained forester developed and managed the Western Shield fauna recovery project, including the 1080 bait development program. Instead of wasting time researching the best methods to employ, he introduced a practical system to get things going. As a former Director in CALM said, “because we have about 30 species of native mammals on the brink of extinction, we don’t have the luxury of sitting back and waiting while theoretical ecologists come up with a magical cure”.

Western Shield was a great success. The program was expanded from the initial 700,000 hectares (of northern Jarrah forest and the Wheatbelt) in 1996 to cover 3.8 million hectares between Esperance and Karratha. The early recovery of animals across the state was remarkable. Of the four main species monitored, the woylie, chuditch, quenda, and the brushtail possum recovered well. The woylie was even removed from the threatened species list.

In the early 2000s however, the situation changed, and many of the species that had started to recover began to decline. Research indicated that feral cats were now the primary issue. The fox numbers declined, and the cat stepped in. But by then, any influence foresters had over this program was minimal, and it is no surprise that the whole program suffered this setback.

Concluding remarks

Next time you hear the green activists crow about saving the south-west forests of Western Australia, remind yourself who originally saved the forests, nurtured them, managed them and protected them. The activists have little alternative ideas for these forests. What is clear is their ideas do not involve the professional guidance of foresters. Benign neglect cannot guarantee the forests will remain in perpetuity without suffering damage from an increase in the incidence of wildfires and disease.

It is worth reflecting just what their alternative management model would mean for these forests left to their own devices. It is most likely the forests would lose their healthy vigour. There has been below-average rainfall in the last 20 years in the south-west that is thought to be attributable to the expansive forest clearing in the Wheatbelt during the previous century. It has made the management of the remaining forests a critical issue. Dense regrowth stands as a result of large wildfires, timber harvesting or bauxite mining that are not thinned or actively managed to reduce overall leaf area, will not only decline in health, but will continue to reduce the water yield exacerbating the water deficit problem, particularly during drought years. How would the future managers of the forests preserved in national parks deal with this issue?

Another example is the dismantling of a successful fire management system introduced to the south-west forests after the disastrous Dwellingup fire 60 years ago. The WA Forest Alliance is opposed to the broadscale prescribed burning program. However, given that the scientific evidence has established a relationship between fire intensity and fuel loads, it is interesting to see how the new “forest saviours” will prevent massive wildfires in the future by ignoring the build up of fuel levels.

The benefits of forest silviculture as an adaptive management tool are an anathema to the green activists and the current government. Timber harvesting and burning to protect the forests are no longer seen as forest renewal and protection tools. Instead, they are portrayed as significant threats to maintaining biological diversity. Sadly, the influence of professionally trained foresters has diminished significantly, and as a group of prominent Western Australia foresters recently argued, “it would do no justice to the work of pioneer foresters of 100 years if the influence and involvement of trained forestry professionals were not sustained into the future”. As well-known Western Australian forester Barney White would say, “any fool can plant a tree; but it takes a forester to grow a forest”. Unfortunately the fools now influence how the forests are managed.

The forests themselves will not survive in their current grandeur if the influence of professional foresters is further diminished. People will only then realise who the real forest saviours are and why professional forestry management is critical for saving and maintaining the beautiful forests in Western Australia’s south-west.

Excellent article Robert and applicable to many other parts of Australia.

Spot on Robert. Pass that onto the PM for national interest of future sustainability & resource management.

I know you’ve been a great forester, but I think you’ve found your true purpose…writing about Australia’s sensitive, environmental assets, that the general public are clearly not qualified or informed on, to then muster intelligent voting.

Never knew you had urine balloons thrown at you…mostly ferals on the front line of activism. Our silly government heads are not educated leaders.

You have been busy on your travels. Keep up the great works!

Another well-researched and well-written article thank you, Robert.

One of the intriguing things about the greens and the forests is their silence over the decades about open cut bauxite mining in the jarrah forest. Unlike the ephemeral impacts of fire and logging/regeneration, bauxite mining permanently destroys the forest, and removes the soils in which it grows. Up to 1,000 ha every year has been destroyed since the 1970s. You would think the green demons like Watson and Shultz, portrayed as heroes by the ABC, would have been out there dying in front of the bulldozers – but no, not a word was said, they were too busy denigrating foresters and claiming that prescribed burning and timber cutting were destroying the forests.

It was also interesting to observe their reaction when the research work (by foresters) demonstrated that the real culprits for the loss of wildlife in the forest were foxes and cats, leading to the successful Western Shield conservation program. The greens hated this, and have never publicly acknowledged it, because it did not fit their narrative that the cause of fauna loss was prescribed burning and logging.

Thanks Roger.

Next month’s blog will be looking at the jarrah forests and bauxite mining, posing the question aimed at the Premier, following his feeble excuse to shut down the native forest logging industry: what is the environmental justification to continue clearing prime jarrah forest for bauxite mining, while at the same stopping the sustainable harvest of those trees?

Hello Robert,

I am preparing to give evidence next week to the NSW upper house inquiry in forest industry sustainability, so I have given thought to the issues you have covered. An extract from one briefing note follows.

NSW and Australian environmental regulatory frameworks are rooted in a wilderness (no need to manage) and terra nullius view, which denies the role of Aboriginal fire management in the development of the Australian biota over the past 50,000 years.

This framework must be rewritten to incorporate an active and adaptive approach to fire and biodiversity management. The precautionary principle must change from an excuse to do nothing, to a guide to progressively implement active and adaptive management across Australian natural landscapes.

Why is a bipartisan approach to sustainable forest management needed? The current political decision making is dominated by a populist eco-political agenda driven by multi million dollar activist campaigns and the voting intentions of ill-informed members of the public in marginal electorates. Government environmental decisions must be based on practical scientific research, not wilderness worshiper theoretical models, that ignore the Scientific Method.

Hi Peter.

Good luck with your appearance at the inquiry. As you and I both know, the political process is stacked heavily against us.

My fear is that the current trajectory will continue and professional land management in native forests will disappear in Australia.

It will take 10, 20, maybe 30 years, or even longer where the forests will be ravaged by constant high intensity fires and the it will slowly dawn on the people that benign neglect will lead to a decline in biodiversity.

Of course the green academics will continue to deflect the real issues so they can keep getting funding for their junk science and build their little empires, getting rich at the tax payers expense.

While I am lying on my death bed, I may get the pleasure of seeing the wheel slowly start turning back in favour of active and adaptive management policies that were favoured by foresters aimed at making the forests healthy again. This is starting in the USA. And there may be the utilisation of native timber again, the great renewable resource that helped build Australia out of poverty.

But then again I will probably die an angry old man saddened by the environmental damage and wilful destruction of our forests.

Very well written and researched Robert.

Little do these so called activists know about bush management and little do they know how the bush is looked after by the foresters.

I can only talk about Tasmanian forests. I bet 99.9 percent of these activists have never held an axe.

Keep up the good work.

Have you considered that it was in fact forestry personnel and machinery that introduced dieback to the jarrah forests because they were in there removing trees and ‘managing’ them?

Also, there is a contradiction here. Bushfire Front sympathiser/member(?) Bernie Masters shared a graph with me that was supposed to prove there have been less wild fires since forest management began. However, this statement in your article contradicts that: “The last 67 years of data leaves no doubt that when the area of prescribed burning is reduced, there are more uncontrolled wildfires.” The pro-burn lobby are constantly bemoaning the reduction in prescribed burning over the last couple of decades, yet this comment states that although there has been less prescribed burning, and as Bernie’s chart if accurate confirms – there has also been less wildfire. Confused logic.

Another contradiction: “Unfortunately, the green activists and politicians don’t understand that it is mainly an even-aged stand over 260 years old and nearing its eventual demise, with many trees already showing a significant crown decline. Over the next few decades, the trees will gradually die, and unless a major disturbance such as a clearfell logging operation or a large wildfire occurs, it could eventually disappear.” This statement suggests that wild fire is critical to maintain the health of karri forests.

There is clearly no science to support the pro-burn lobby’s theory that prescribed burning prevents or reduces the prevalence or frequency of wildfire. Burning random forest blocks many kilometres from infrastructure and hoping that it will either mitigate or prevent a wild fire is ludicrous, especially when so many fires are ignited by lightning which is completely unpredictable. A disproportionate number are also ignited by humans.

Noongar people tell me they NEVER burnt the forests. There was no practical reason to do so. Burning camping areas and tracks, and flushing out fauna for hunting occurred in grassland areas. When they did burn, it was ‘barefoot’, they raked around any trees, controlled the rate of the fire using small branches and the burns were very small and mosaic. DBCA’s current ‘prescribed’ burning program, where large blocks are burnt frequently, very hot, with crown scorch and ground litter and vegetation burnt to charcoal bears NO resemblance to traditional burning practices and it is offensive to suggest otherwise.

In reply to Dr Michelle Frantom.

Michelle, I have no idea what field of science you studied to get your doctorate, but some of your comment shows a high levee of naiveté, particularly in relation to fire management.

Firstly, my statement about 67 years of data mainly applies to the eastern states, where a dramatic reduction in broadscale prescribed burning has led to an increase in severe wildfires, as witnessed just this century. I should have made that point clearer in my blog, but thanks for highlighting the confusion it created.

Secondly, my story acknowledges the outbreak of Phytophthora dieback in relation to forest management. I go to great pains to highlight how it was subsequently managed by forestry professionals and became a template for all other agencies to deal with the problem.

Thirdly, in relation to karri forests, they provide a conundrum to ecologists and foresters in that these forests grow in a relatively high rainfall environment (>1100 mm per annum) with a limited summer drought of less than three months duration.

Elsewhere in Australia, such a climate would support rainforest if protected from fire. In southwestern Australia there are no continuously regenerating and fire intolerant rainforest species to compete with karri, although geological and biogeographic evidence point to the existence of rainforest in the distant past. The cause of its disappearance appears to be Tertiary aridification and the increase in landscape fire.

The massive size of karri trees and their reliance on fire for regeneration—through the mass release of tiny seeds with limited reserves onto nutrient-rich ash beds—indicate convergent evolution with other distantly related eucalypts, such as mountain ash in southeastern Australia and flooded gum in northeastern and eastern Australia. This convergence suggests that these species have been shaped by similar natural selection pressures, adapting to compete with rainforest species by using fire as a tool for interspecific competition. The remarkable diversity of the Eucalyptus genus, along with the independent evolution of traits like gigantism across different lineages, and parallel patterns of diversification in numerous other groups, strongly support the conclusion that fire has been a fundamental part of Australia’s environment for millions of years, long before human colonisation. Aboriginal people, therefore, adapted to coexist with this naturally fire-prone landscape.

Eucalypt forests are disclimax communities. We know that karri can only survive through disturbance. Depending on the ecology of the forest type, depends on the scale of the disturbance. In the case of kauri forests, they require a hot fire to aid in regeneration.

The statement you refer to suggests exactly what I said – karri forests depend on major disturbance to survive, be that clearfall logging followed by a hot fire, or an intense wildfire. In today’s world where we have a large number of valuable assets and lives living within the karri forests, simply relying on a large wildfire to maintain karri forests and destroy everything in its path is not a sensible approach to take.

For the reasons I outline above, contrary to your assertion, I maintain there is no science backing the activist green philosophy that keeping human fires out of the landscape is good for the environment in south-west WA.

If you want to talk about Aboriginal management of the forests, I suggest rather than relying on anonymous Nyoongar people, you have a read of Sylvia Hallam’s seminal book which reflect the ecological realities I highlight above. I am sure you will learn something and perhaps reflect on what you have written. It is a majestic pioneer memoir on the interconnections between Aboriginal society, Country and the varied applications of deliberate firing, and that summary is not my words by the way.