While finalising a previous blog with Ian Ravenwood on the evolution of aerial operations on Surrey Hills, I was reminded of the tragic plane crash on Daisy Nolan Hill, near Hampshire, in 1983, which killed the sole occupier, pilot John Lindridge.

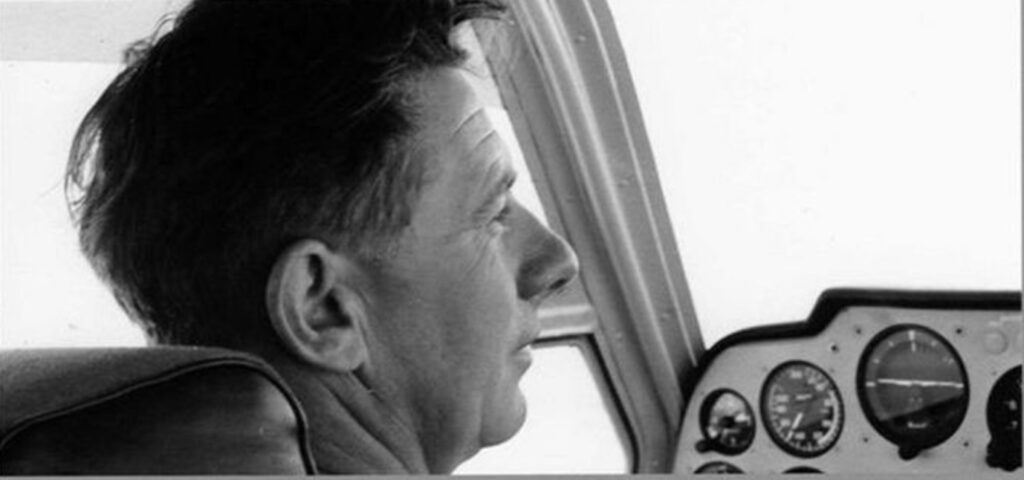

I researched what I could about John and quickly discovered he had a remarkable flying career, first as a pilot with a flying medical service in outback South Australia in the 1960s, then part of critical freight and transport in the Bass Strait to more flying in Tasmania. John has a connection with Surrey Hills. He was involved in the aerial burning operations for Associated Forest Holdings (AFH) over Surrey Hills and nearby lands. He was a favoured pilot because he flew smooth and sensibly, unlike some of the younger pilots who flew like it was a fighter plane.

With the assistance of his family, I have put together John’s story as an enduring legacy of his flying career and selfless contribution to society. While the family now has an unfortunate association with the forests at Hampshire Hills, their husband, father and grandfather deserves recognition beyond the accident that took his life.

The fateful day

Early on Saturday, 12 April 1983, John was called out for an urgent medical flight to transport a 16-year-old Rosebery boy to Melbourne. He required urgent microsurgery to rejoin his severed left hand following a car crash the night before on the Murchison Highway near Mt Black.

John drove from home at Ulverstone to the Devonport Airport. He left in a Beechcraft Baron headed for Wynyard airport to pick up the patient.

Soon after take-off, it is believed John suffered an event that incapacitated him, and he managed to put the plane into autopilot. Instead of flying west along the coastline, the aircraft continued its south-westerly direction from the runway and flew in a straight line towards Highclere. John’s wife Marie typically heard the plane fly to the north of the house when it was on a westerly flight path. On this morning, she heard the plane but with a much louder noise and it flew to the south of the house. It seems the plane was still in full thrust, was flying lower than normal and hadn’t reached its cruising height.

At around 5:10 am, near Hampshire, resident, David Watson was out collecting his newspaper. It was dark, and there was low cloud. He could not see the plane but heard its engines running smoothly and noticed its lights. He thought it was flying very low towards the hills in the area. Next, there was a loud thud and a glow like a moon about five kilometres away. Mr Watson notified the Police, and a search for the plane commenced in the air and on the ground. Another witness was a retired RAAF pilot. He said he saw the undercarriage open and the lights come on shortly before the crash.

At around 10:00 am, smouldering smoke alerted searchers to the plane’s location. Thick bush hindered access, and an AFH bulldozer was brought in to clear a track to the crash site.

A coroner’s inquest was held into the accident. It was found that John’s last routine medical examination showed an abnormality on his ECG test that was put down to an issue with the machine. At the inquest, a pathologist said a post-mortem examination had “revealed a few areas of myocardial fibrosis of the type associated with ischemic heart disease”. John received a letter from the Department of Aviation around February 1983 requiring him to go to Melbourne for his subsequent medical examination because of an irregularity in his previous ECG test. It was the first time he heard about an “irregularity”. While John was anxious about this, his wife explained they would have notified him much earlier if there were any problems. John sought an explanation from his doctor and was given assurances and told he was fine to continue flying. John also spoke to a couple of other pilots who told him they had to get another test at that age and the examination in Melbourne was precautionary.

John was due to fly to Melbourne on the Monday after his fatal accident. At the inquest, the Department of Aviation could not explain why there was a delay in organising a second medical examination, which may or may not have prevented him from continuing as a pilot because of his heart condition. However, it most likely would have led to appropriate treatment for his heart condition if detected.

The coroner concluded the cause of the accident was the incapacity suffered by John shortly after take-off. The coroner praised his efforts to prevent the plane from crashing in the heavily populated Devonport area and had done an excellent job keeping the plane airborne for so long. No emergency radio calls were heard. It is believed John may have regained consciousness. He groggily prepared the aircraft for landing in a dazed state with instrument warning alarms ringing inside the plane due to its low height. He was alive just before the crash because there was some control of the aircraft as it turned into the crash, and its landing lights had been switched on seconds before impact.

The coroner concluded that John was a competent and experienced pilot flying a well-maintained aircraft.

Early life and first pilot job

John grew up in Newington in the English County of Kent. As a young teenager during WWII, he joined the RAF and became a first-class instrument mechanic, which inspired his love of flying. After his military training, John worked at the nearby Kemsley paper mill as a machine man at the behest of his father, who also worked at the mill. It was expected that John would have the same career as his father, who worked at the mill for over 50 years. However, John couldn’t bear the thought of living in a small terrace house while working in a factory and wanted to see more of the world. So he arranged a transfer to work at the APPM pulp and paper mill at Burnie. In 1955, he left for Australia as a “ten-pound pom”.

He studied at night at the Tasmanian Aero Club to get his commercial pilot licence while doing his day job at the paper mill. It was during this time he met school teacher Marie Morse at church, and they married in 1957.

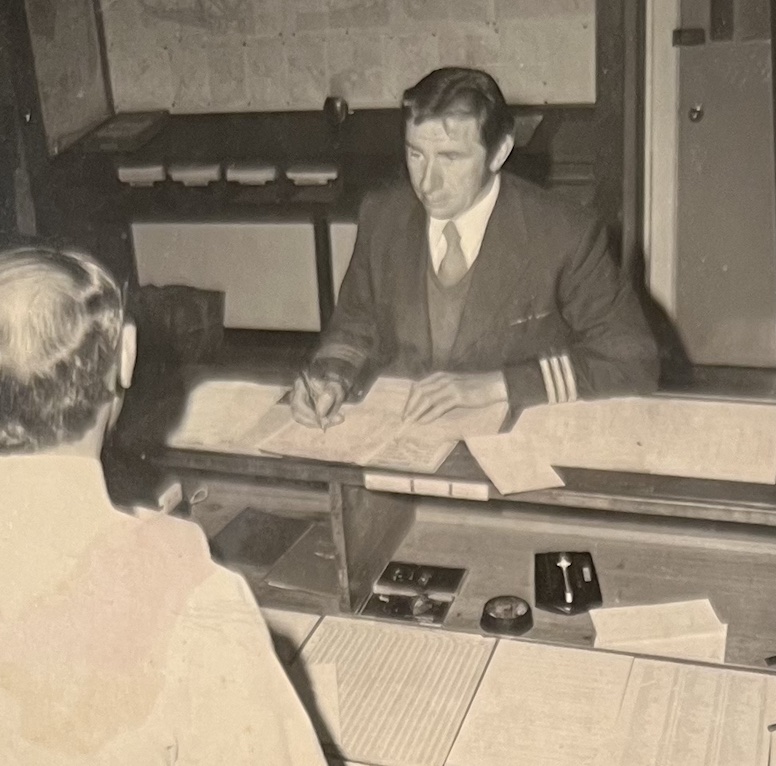

After getting his commercial pilot’s licence, John was alerted by his wife to a job with the flying medical service run by the Bush Church Aid Society (BCA) in South Australia. BCAS started in the late 1930s with a single light plane. However, by the early 1960s, the flying services were in strong demand in the vast outback, and the BCA purchased a second Cessna to complement the Cessna 210 they had bought earlier, and advertised for a pilot. With a Christian sense of vocation and his newly acquired pilot’s licence, John successfully applied for the job in 1961, and he and Marie packed their bags and moved to Ceduna.

Both John and Marie were looking for more in their life at that young age, not that living in a fibro-cement house at Ceduna wasn’t challenging and isolated. On the contrary, it was a barren, dry and dusty place. Ten days after arriving there, their first child Gillian was born, and two boys followed with Michael in 1963 and Geoff in 1966. For John, he managed to see the vast outback and experience plenty of adventures within the routine flying visits of doctors and nurses to the outback towns. For Marie, she had support through the BCA, and they became part of the local community, meeting wonderful people, some of whom have remained life-long friends. Marie helped at the hospital and was the Secretary of the School of the Air Mother’s Club.

John was required to land in whatever the conditions. In some cases, on the Nullarbor, there were caves under the runway, and potholes would appear after rain. He had an unfortunate incident on the very rough runway at Cook, a railway town halfway between Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. The nose of the aircraft was damaged after trying to land on an uneven surface.

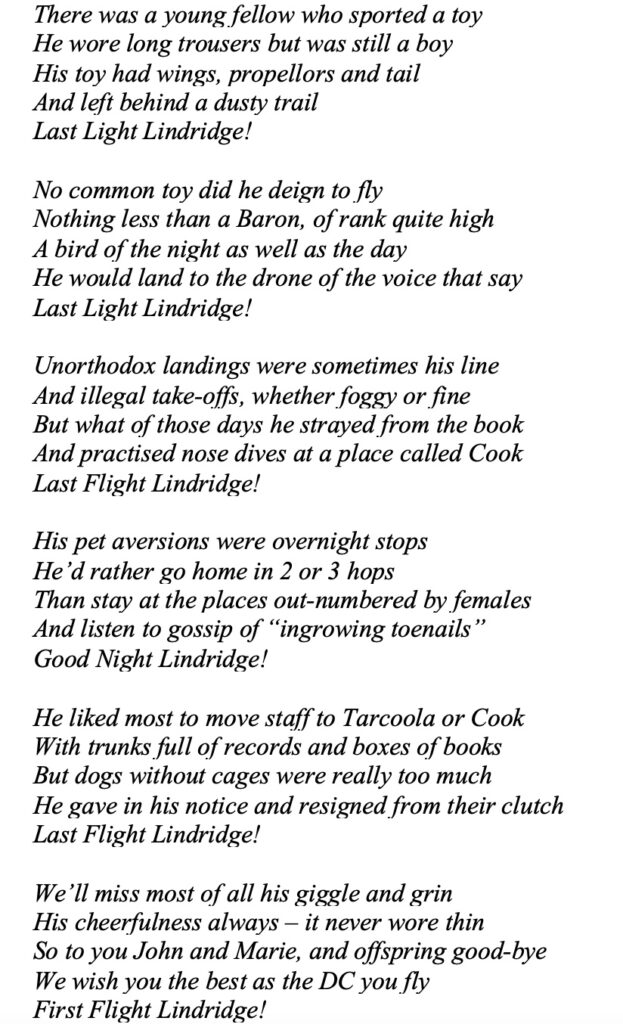

As a rule, he was required to land before dark to avoid the airport putting on the runway lights and then reporting this to the aviation authorities. As a result, he earned his nickname “Last Light Lindridge”, as he always managed to land before the last light (see poem below).

John later acquired his night flying rating, which allowed him to fly at night without a valid medical reason. In addition, it allowed him to bring the doctor home at night after a day’s consulting.

Marie recalls one incident when they received a call in the middle of the night from the only residents of an idyllic island off the Eyre Peninsula, near Elliston. A frantic wife found her husband’s dinghy washed up on the shore with him missing. He had gone out to check his large boat was still moored securely during the gale force winds. They were the only ones living on the island. John flew out with the Harbour Master and the matron. The frantic wife had to drive the tractor to the end of the runway with its light left on and place lanterns along the runway. After safely landing, the Harbour Master rowed out in the dinghy and found the husband safely on his boat. He was unable to row back to shore because the dinghy had drifted away. John arrived home at 3 am with Marie puzzled to see her husband getting out of his wet clothes – he was supposed to be flying planes, not boats!

There were many trips to treat sick people and mercy dashes to save lives, such as Aboriginal babies with gastroenteritis, miners falling down opal mineshafts and landing on the Nullarbor for a car accident. One patient was violently sick all over John and the control panels. When John was cleaning the plane afterwards, he found a pair of dentures. On another occasion, John was called out at midnight to take the doctor to Kingoonya, where a man collapsed at a dance. A suspected brain haemorrhage turned out to be a heart attack. They flew the man to Woomera hospital. John and the doctor arrived back at Ceduna at 5:00 am. Needless to say, neither attended the church service that morning.

John was fortunate to work with chief pilot Allan Chadwick, the original and only pilot of the flying service since 1938. Every month was busy for the two pilots covering such enormous areas. A typical month involved transporting up to ten patients to hospitals, racking up nearly 10,000 kilometres of flying. In 1966-7, the BCA carried out investigations to replace the Cessna’s with a twin-engine aircraft. They selected the six-seat Beechcraft Baron B55. John loved the faster aircraft despite dealing with minor mechanical defects when learning to fly the new plane. Instead of taking one hour and twenty minutes to fly from Ceduna to Cook in the Cessna, the Beechcraft took only one hour and a trip to Adelaide with a patient requiring specialist treatment was reduced from two hours to one hour forty minutes.

In early 1967, the BCA began assessing the viability of its flying medical service. This was precipitated by the resignation of their doctor and the difficulties in finding a permanent replacement. The final straw was the dramatic drop in radio work following a PMG radio phone installation at Coober Pedy. As a result, BCA decided to bring down the curtain on its long and eventful service in 1968 that covered some 130,000 square kilometres based out of Ceduna. The Australia-wide Royal Flying Doctor Service took over their work.

A new job based out of Melbourne

John and his family then moved to Melbourne, where he took up a position as a pilot for Brain and Brown Air Express (BBA), initially flying Douglas DC-3s and Bristol Freighter planes as part of their air freight service between the mainland and Tasmania and the islands of the Bass Strait. This was during the Commonwealth government’s “two airlines” policy which created a duopoly of Trans Australia Airlines and Ansett Airlines to service the air cargo routes between the capital cities. They would transport passengers by day and freight by night.

While in Melbourne, John sat for his Senior Commercial Pilot’s Licence exams to become a Captain. He excelled in his role and trained many second pilots. The business appeared to thrive, transporting a whole range of goods to Tasmania and the Bass Strait. They developed a fully integrated haulage system complete with warehouses, mechanical loading, and specially designed conveyor equipment. But the reality was that only a very small tonnage of all freight was carried by air, the rest was by sea, and it was very a competitive business.

However, the smaller air freight companies such as BBA were hamstrung by not being able to import large jet engine aircraft more suitable for their operations to replace their older aircraft that were uneconomic. In 1977, the new BBA owner, IPEC, sought to import planes. Reg Ansett argued it was not allowed in the two-airline agreement and the matter headed for court. Unfortunately, BBA went immediately into receivership and John suddenly was out of work. A shareholder of BBA was Lindsay Fox, and he described the business “was like the air adventures of Biggles. We couldn’t make money out of it”.

Return to Tasmania

John and his family returned to Tasmania and settled in Ulverstone in 1981. He was now in his early-mid 50s and semi-retired from flying. For a pilot his age, it was difficult getting employed. He took on contract work in the state’s north-west, happy to do air ambulance work in Tasmania.

He also picked up work with AFH who carried out aerial burning operations in the north-west, including Surrey and Hampshire Hills. Plantation manager Les Baker had a pilot’s licence, and John used to let him fly not only because Les knew where to go, but he was also keen to tally up some flying hours. Les recalls flying in the Britton Norman Islander. He said it was a great plane that could go slow and turn without stalling. He had a lot of admiration for John’s piloting skills, and they could not get out of bed early enough to get to work to fly as they both loved the job.

John’s youngest son Geoff fondly remembers a flight he took with his father around Christmas 1982. Flying for Munro Aviation, they left Launceston airport in the Britten-Norman Islander to fly to Bridport. Then they island-hopped around Flinders Island, making at least 6-8 landings to drop passengers and freight. The plane only needed a very short runway and was highly manoeuvrable. Geoff recalls the steep banking just before landing to make sure the runways were clear of cows.

There is no doubt that John loved his planes and flying. He deserves to be remembered for much more than his unfortunate accident that took his life at Daisy Nolan Hill. His selfless devotion to helping people in need, mentoring younger pilots, and above all, his flying skills.

Rest In Peace, Captain John Brian Lindridge 1928-1983.

Poem – “Last Light Lindridge” – written by a nurse from BCA and read at his farewell

Another pioneer brought to life thanks for sharing.

Peter

Great read, thank you.

Well done Robert. Like many of my peers, I was aware of the crash and its location but knew nothing about John until now. You have honoured a well-lived life.

Great read. I always wondered whether he was heading to the AFH airstrip.

Interesting reading.

I was in the Wynyard Aero Club in the !970s and remember well the North Broken Hill Cessna Citation 502 Jet crash in WA on the way to Robe River.

One of the chaps on board later worked at the Burnie pulp mill, and another one was the Tonganah clay mine (near Scottsdale) manager.

A very interesting read Robert. So sad, the first part though.

I am fascinated by the S J Kirkby marking on the BCA plane and I was looking for an Antarctic connection. I met a Syd Kirkby who had spent years in Antarctica before I did in 1968. I was wondering if there was a link.

Again, well done.

Winston.

I think the SJ Kirkby on the BCA plane would be for Bishop Kirkby the founder of BCA.

Good work Robert, nice to know you are still researching this area.