Introduction

Sandalwood is a highly aromatic timber that has been harvested in Asia over centuries for many uses. The main one has been burning powder from the tree in joss sticks as incense and forms a significant part of religious ceremonies. In Australia, Aborigines had many cultural uses for sandalwood. Some species can be carved into delicate products such as inlaid boxes, ornaments and incense holders. It is also used to deter troublesome insects. In addition, oil is extracted and used to make soaps and perfumes and used for medicinal purposes. For example, before penicillin, it was used to treat venereal diseases.

The many uses of sandalwood and its religious significance, combined with its relative scarcity and slow growth rate, have made it a precious commodity for trading. Where it does grow overseas, it is consumed domestically. However, in places like China and Singapore, where it does not grow, demand for sandalwood products is very high.

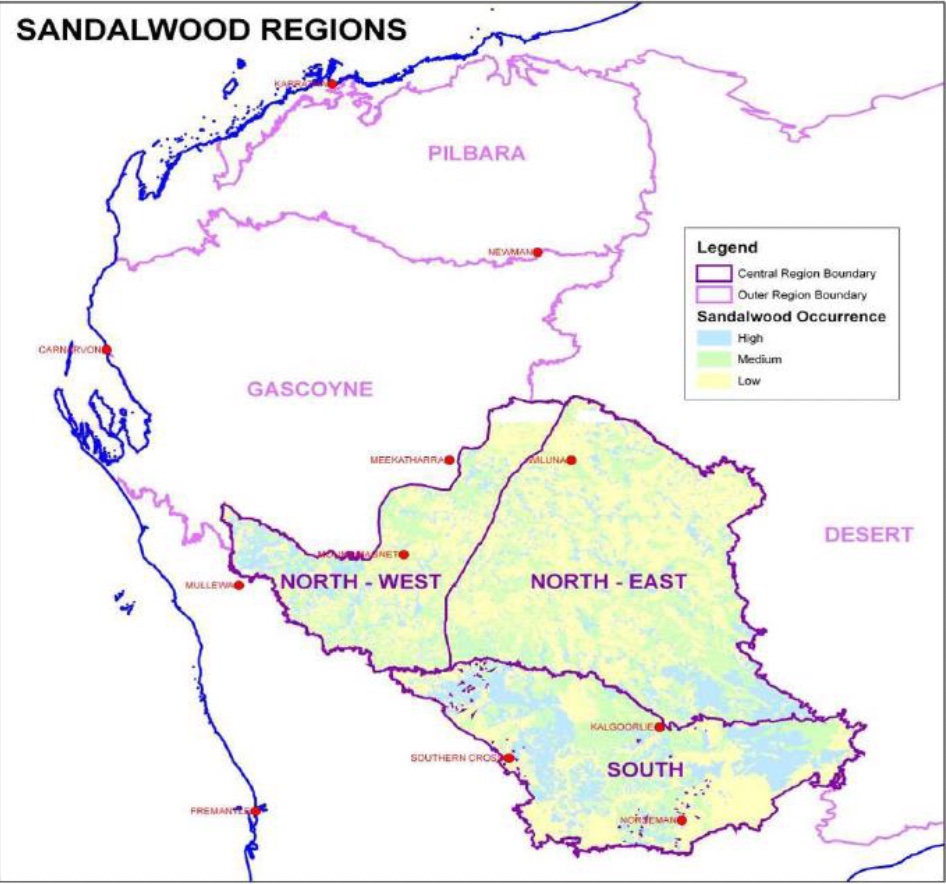

Australia has several native Santalum species, but only two – Santalum spicatum and Santalum lanceolatum produce the true sandalwood fragrance. The former occurs mainly in Western Australia over a wide range, extending to the Nullabor Plain in South Australia. The latter species occurs throughout northern Western Australia, northern Australia, north of Cairns, and the Hughenden-Cloncurry area, both in Queensland.

Opening up the Western Australian sandalwood industry

In the early part of the nineteenth century, the British, having used their imperial tentacles in India, were heavily involved in the sandalwood trade. They established plantations at Mysore in India to supply the lucrative Singapore market.

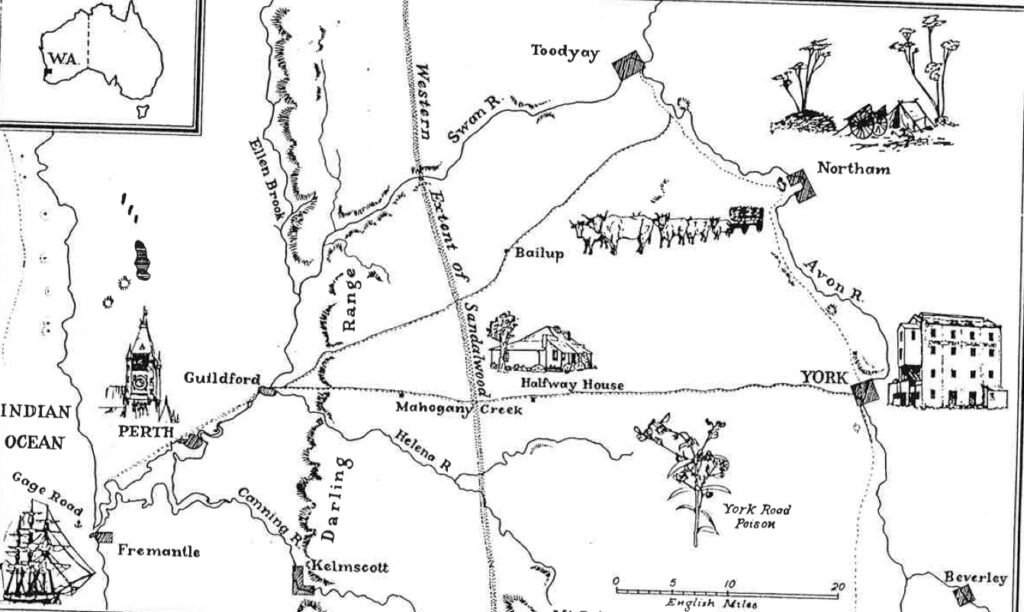

In 1843 a report reached Perth about the high prices for sandalwood exported out of Sydney from trees sourced from the Pacific Islands, most notably Fiji. It followed the discovery of what was believed to be a similar tree east of the Darling Range. However, the local sandalwood species was only used for firewood and fencing as its value was unknown.

At that time, the Western Australian colony had a significant trade imbalance and was desperate to find a commodity to export to overcome its financial struggles. The magnificent timbers from the forests of the south-west, in particular jarrah, were already heavily promoted in England but recognising their true value wasn’t immediately apparent. So, in an attempt to establish a market for Western Australia’s sandalwood in Asia, an experimental shipment of four tons was sent to Bombay in 1845 to test the market. It was favourably received and attracted very high returns. While it was considered inferior to the Timor and Indian sandalwood (Santalum album), having a lower oil content, its aromatic quality was excellent, and there was significant demand from joss stick and incense makers.

The primary activity of sandalwood harvesting was based around the Avon Valley, where trees were cut down by axe, stacked on a cart and sent to Fremantle. Over 1,335 tons were exported within three years, and sandalwood became the state’s most valuable export commodity, surpassing wool and whale oil.

However, the good times didn’t last long. The few main roads became clogged with sandalwood traffic and quickly deteriorated. This caused conflict with other roads users. The government introduced export taxes, tolls and licences to fund road making and repairs. These added costs were exacerbated by the need to explore further away from the ports to source more and more sandalwood. Plus, an oversupply in China caused a drop in prices. All these factors combined meant the cutting of sandalwood in Western Australia practically ceased in 1849.

Sandalwood cutting continued on a much smaller scale as a form of secondary income during a phase of rapid agricultural and pastoral expansion. The tree was cut and stacked until sufficient quantities were attained for transport. It was soon discovered that sandalwood foliage provided excellent feed for sheep and cattle.

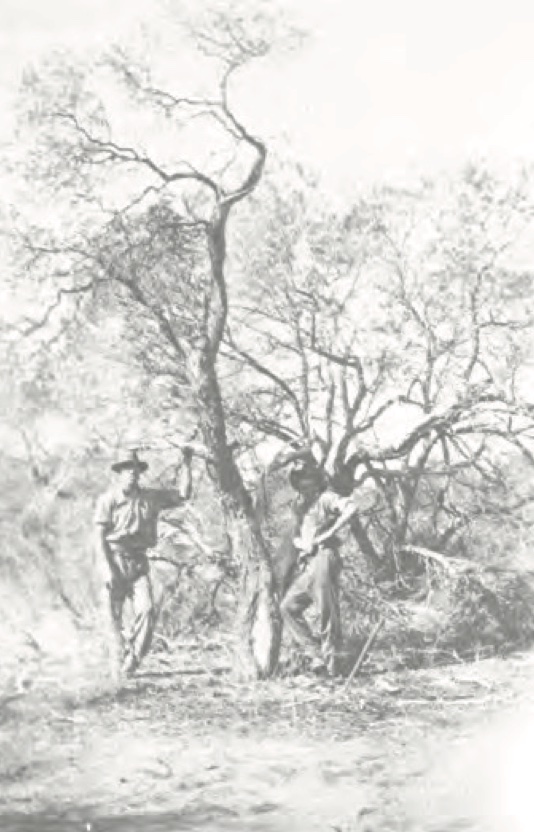

Sometime in the 1870s, the Mysore plantations failed to produce enough sandalwood, and there were trade restrictions out of India. Sandalwood sales from Western Australia increased threefold to fill in the gap to Singapore. All the accessible areas were cut out a decade later. The butts and roots were found to be a valuable source, so they were pulled out by horses and camels using chains – hence the common vernacular of “pullers”. The pullers searched well beyond the settled areas for virgin stands of sandalwood. They camped at water holes or dug their own wells as they pushed further inland. They ultimately pioneered settlement into the country that later became the Wheatbelt.

The discovery of the gold and the development of the Western Australian goldfields in the mid-1890s provided railways that not only gave access to vast areas of uncut sandalwood but an easier path for transporting to the coastal ports for export. As surface gold became harder and harder to find, prospectors turned to sandalwood cutting. They found new stands further east, which created a new boom in the industry from 1896 until just before WWI. The cutters were itinerants living in tents trying to live off the inland country. Some even had their young family travelling with them.

Early management

As early as 1876, legislation was introduced to limit the over exploitation of sandalwood trees. The cutting of ‘miniature’ or undersized sandalwood was prohibited, and the act provided a mechanism to establish sandalwood reserves.

Foresters attempted to control the cutting of sandalwood on a somewhat sustainable basis. The state’s first professional-trained forester, John Ednie-Brown, introduced sandalwood plantations in the 1890s to conserve and extend the resource with limited success. Unfortunately, germination was patchy, and rabbits destroyed most seedlings. Ednie-Brown died soon after, and it wasn’t until Charles Lane-Pool was appointed the first Conservator of the newly formed Forests Department in 1918 that there was any serious sandalwood management program. Lane-Poole initiated the first steps to control the cutting of sandalwood trees, even though this came after the two earlier major sandalwood cutting booms.

Regrowth was minimal mainly because of a lack of understanding of the parasitic nature of the tree. It was compounded by pulling out the sandalwood roots and the widespread clearing for agricultural purposes.

An engineer employed by Lane-Poole was given the task of fully understanding the sandalwood industry. In an old plantation at Meckering, he noticed that flourishing trees were growing close to jam trees (Acacia acuminata). His theory was that jam trees were hosts for parasitic sandalwood trees. A government botanist, Charles Gardner, confirmed his theory. Lane-Poole then set about planting sandalwood with host trees. There was a successful seed collection program via school children who were offered a reward of “sixpence per pound”.

Before the Great Depression, four prominent companies exported sandalwood to Singapore and China. However, a civil war in China led to the sudden collapse of the export market and left huge stocks sitting on the docks at Fremantle. Pullers, who traditionally earned a basic wage, were supported by the government who offered to underwrite the unwanted stocks if the four companies merged. The Sandalwood Act, 1929 was passed, and the following year the companies merged to form the Australian Sandalwood Company. The industry continued at more moderate pulling levels associated with the clearing of the Wheatbelt and some rangeland harvesting.

Under the Sandalwood Act, quotas and licences with conditions were introduced. For example, there was a minimum size that green trees could be harvested. This changed over time, and now green trees have to be greater than 127mm in diameter (about 41/2 inches) at 150 mm above ground level. For ease of measurement, this was around the same size of a jam tin, popular on the goldfields.

The aim was to try and conserve the resource to allow smaller trees to continue to grow and develop and maximise utilisation and the heartwood to sapwood ratio efficiently.

Other licence conditions related to tree selection and silviculture included sandalwood cutters having to plant a minimum of 12 fresh sandalwood seeds beneath nearby host trees for each tree harvested.

Current management

Demand for sandalwood from Western Australia remains high. The silvicultural management of sandalwood is complex as sandalwood species are root parasites that require viable host plants over the tree’s life. Being a root hemiparasitic plant, it is dependent on host trees for water and certain nutrients. It loves growing near nitrogen-fixing plants such as wattles.

The sandalwood industry has been subject to many reviews and enquiries throughout its history. It has always generated controversy mainly over a perceived belief that native sandalwood is being cut well beyond sustainable levels.

After the formation of the Forests Products Commission (FPC) in 2000, opposition to aspects of the industry increased along with calls for another inquiry into sandalwood harvesting to examine the sustainability of utilising natural sandalwood. There was a Parliamentary Inquiry into Sandalwood in 2012, where staff from the then Department of Environment and Conservation and FPC were questioned on sandalwood management. They gave indications that regeneration was inadequate and current harvest levels were unsustainable, despite licence conditions and increasing work by the FPC as outlined under Operation Woylie below.

The inadequate regeneration due to a lack of natural dispersal, and grazing by rabbits, sheep and goats, has meant an inevitable decline in the sandalwood resource even without harvesting. Forest consultant, Jack Bradshaw, argues that common concepts associated with working under a sustained yield in forests is not applicable to the sandalwood areas. In a report he produced in 2009, he suggested that harvesting and regeneration activities should occur at levels that would maintain the numbers of seed bearing sandalwood as high or higher than would occur without harvesting and regeneration.

Sandalwood management was addressed in a management plan in 1991 that proposed a reduction over time of wild harvest and transition to plantations. Following research from 1987, sandalwood tree farms, or plantations, have been established on farmland in the Wheatbelt. This program has accelerated since 2007 under Managed Investment Schemes. The primary aim of these plantings is to supplement the supply from native stands. Considerable Indian sandalwood (Santalum album) plantations have also been established in the tropical north in irrigated plantations as part of the Ord River Irrigation Area.

Most stands of naturally occurring sandalwood are on Crown land – very little remains on private land. The now Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions is responsible for sandalwood management and licences. The FPC manages the harvest of sandalwood for the government on Crown Land. There is currently an annual quota of 2,500 tonnes per year. At least half has to be from deadwood, which is unsuitable for oil extraction.

I have read reports that this annual cut is a sustainable figure. But there is a recent paper in the Rangeland Journal claiming sandalwood is “on a path to extinction in the wild”. Unfortunately, the problem with this paper is it contains some dated information. The FPC have not published any of their detailed inventory data and modelling that underpins the allowable cut of sandalwood, and hence the paper’s authors relied on selective and partial information, making up their own interpretations.

It led to calls to stop wild sandalwood despite the limitations of that study. The focus has been on the misleading reference to the annual quota of 2,5000 tons per annum without highlighting that 50 per cent is made up of deadwood and the remaining 50 per cent of actual green wood cut, which has rarely matched the permitted quota in most years anyway.

There has undoubtedly been considerable angst about the naturally occurring and mature sandalwood harvest levels. The current stand structure is a result of 150 years of history and utilisation. There are claims there is likely to be a “gap” between when the existing resource of living trees is cut out and when the successful regeneration of the new crop attains an age that can be harvested again.

An officer from FPC gave evidence at the Parliamentary Inquiry that the “gap” is “possibly 100 years”. However, Bradshaw believes the concept of a “gap” is an oversimplification and does not make sense. Measurements from inventory plots show that the tonnage of sandalwood in the greater than 126 mm diameter cohort will increase naturally for the next 40-60 years as the relatively large number of stems in the 75-126 mmm size class moves into the large size class.

For his 2009 report, Bradshaw used data from the 2001 inventory program that was initially set up to test the effectiveness of the new regeneration system known as the Sandalwood Enrichment Program. Over 1,286 inventory plots were established in the field and a further 60 were randomly selected to reduce bias in the selection of the original plots.

In the meantime, it has also been essential to moderate the proportion of low-grade juvenile material from the tree farms to avoid reducing quality until they produce trees that provide more heartwood. The fear is that any reduction in product quality will ruin the reputation of Western Australian sandalwood in the market. Therefore, carefully blending the higher grade naturally occurring sandalwood from government-managed stands with the privately managed tree farm resource has occurred. To maintain that product quality, the ongoing availability of wood from the native stands is required under the currently approved quota until 2026, when it will be reviewed and new quotas determined.

The challenge is whether there will remain access to native sandalwood into the future for blending purposes and whether the plantation-grown resource can attain a level of quality to stand on its own and deliver a high-quality product to meet market demands. The essential product is the heartwood, which contains most of the oil and the scented wood. The optimum rotation length for the tree farms to produce wood similar to the naturally occurring material is estimated at 25 years. However, plantation sandalwood is renowned for low survival and slow growth rates. Therefore, it is still unclear whether that estimated figure for high-quality heartwood production from plantation trees will be attained.

Operation Woylie

The Woylie (Bettongia penicillata) or brush-tailed bettong is a small native marsupial uniquely linked to the Australian sandalwood tree. The Woylie is the size of a guinea pig and moves around by hopping on its hind legs. It has a long, flexible tail, similar to the possum.

Sandalwood requires a seed disperser for successful recruitment, and in the past, the Woylie played an essential role in dispersing and caching seeds. Studies investigated the role of woylies in the regeneration of sandalwood. After collecting the delicious sandalwood seeds, the woylies carry them in their cheeks before burying them to hoard as future food stocks. The seeds can be carried as far as 50 metres away, which contributes to the regeneration of sandalwood. The act of digging also assists the ecology of sandalwood by dispersing highly beneficial fungi.

Since European settlement, the distribution and numbers of woylies have decreased dramatically from their original distribution across the south-western third of the continent.

The Woylie was initially found in great abundance across southern Australia. However, by the 1920s, it was extinct over much of its range. Factors attributed to this decline include habitat loss, the introduction of feral predators such as the cat, the European red fox, disease and competing herbivores.

In 1996, after a very successful 1080 baiting campaign by the Department of Conservation and Land Management, the Woylie became the first Australian animal to be removed from threatened species lists due to active management in controlling foxes and cats. However, since 1999, small native mammal populations throughout south-western Western Australia have undergone unexpected, rapid and substantial declines. The Woylie is now only found in three small Wheatbelt reserves – Dryandra woodland, Tutanning and Perup Nature Reserves. It has been suggested that seed dispersal of sandalwood is limited in areas where woylies have become extinct. For more than 50 years, the natural recruitment of sandalwood was poor.

In 2007, in addition to planting seed at harvest, the FPC established an ongoing research program to improve seed germination and the establishment of sandalwood in its natural environment. Called Operation Woylie, FPC designed a mechanical process to mimic the role of the Woylie in seed dispersal. As a result, an astonishing five million seeds are planted in over 1,000 kilometres of mechanical rip-lines each year. These rip lines are near existing host trees or where host trees have previously been planted. Hopefully, this program will successfully ensure sandalwood thrives in its natural habitats.

The recent wet winter has also proven beneficial for the sandalwood regeneration program. Seeds that have remained dormant due to drought conditions have now germinated on a large scale, up to five years after they were sown.

Conclusion

The management of the native sandalwood resource in Western Australia is very complex. Simplistic calls to stop harvesting will do nothing to protect or save the timber.

Analysis of field data by Bradshaw shows that ending harvesting will lead to the reduction of mature sandalwood trees by about 50 per cent and the seed source by 84 per cent, while the dead wood component would remain stable.

In fact, his work showed that while continued harvesting of sandalwood would reduce the standing tonnage in the longer term, it has no adverse impact on the critical seed source. In areas where harvesting and regeneration activities are already taking place, managers have the capacity to significantly increase the number of seed bearing trees in the long term and increase their dispersal over the landscape.

The sandalwood issue in Western Australia is another example of the erroneous belief that stopping utilisation of a natural resource and reserving it under passive management, without any data to support that position, will immediately provide a better conservation outcome. As with other major land use issues in the country, that is not the case and can actually lead to a worse conservation outcome for sandalwood, as demonstrated by analysis of field measurements and modelling.

As a postscript to this story, I saw an article about one of the largest sandalwood plantation companies at this link:

https://www.fridayoffcuts.com/index.cfm?id=981#12

You will need to scroll to the story on Quintis.

Robert, congratulations on a very informative overview of the history of the industry and the silviculural management issues.

Past over-exploitation of the resource, whether due to greed or ignorance, cannot be redressed by a hands-off management approach going forward.

As with our native forest hardwood sector, the key to a sustainable industry is the primacy of the ecosystem, followed by application of good silviculture.

Yields and revenues should be consequential outcomes, not drivers of resource management strategy.