Introduction

The first Federal battalion of Australian soldiers sailed to South Africa in 1901 to fight the Boer War. They joined colonial troops already serving there. One of the lessons learnt by the Commonwealth forces during that campaign was the need to develop an armament that was a happy medium between a long rifle and a carbine. Another problem was many of the troops arrived with different equipment than that used by the British. The supply of ammunition and the field repair of weapons became an issue and restricted their fighting capabilities in battle. It became abundantly clear that Australia’s isolation from its armament source in Britain would hamper future conflicts. After federation, the new Commonwealth government faced responsibility for the country’s defence. The first task was to make Australia independent of procuring armaments and munitions supplies from the United Kingdom.

While the Lee-Enfield arm was superb, it became evident that the long rifle and carbine, initially produced for foot and mounted use, needed to be replaced with a universal-pattern rifle. The “Shortened Enfield Modified Rifle” was a happy medium, designed in 1901 with new safety features such as an extended handguard, new style rear sight, and hooded front sight protector. Most notably, it had a barrel five inches shorter than the long rifle and four and a half inches longer than the carbine, weighed a pound less than the rifle and eight ounces more than the carbine. The most important innovation was the addition of guides which allowed the rifle to be charged with ten rounds of ammunition from two 5-round sheet metal stripper clips. Further experimentation and trials led to a final product dubbed the short magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) in December 1902. A legend was born.

The Lithgow Small Arms Factory

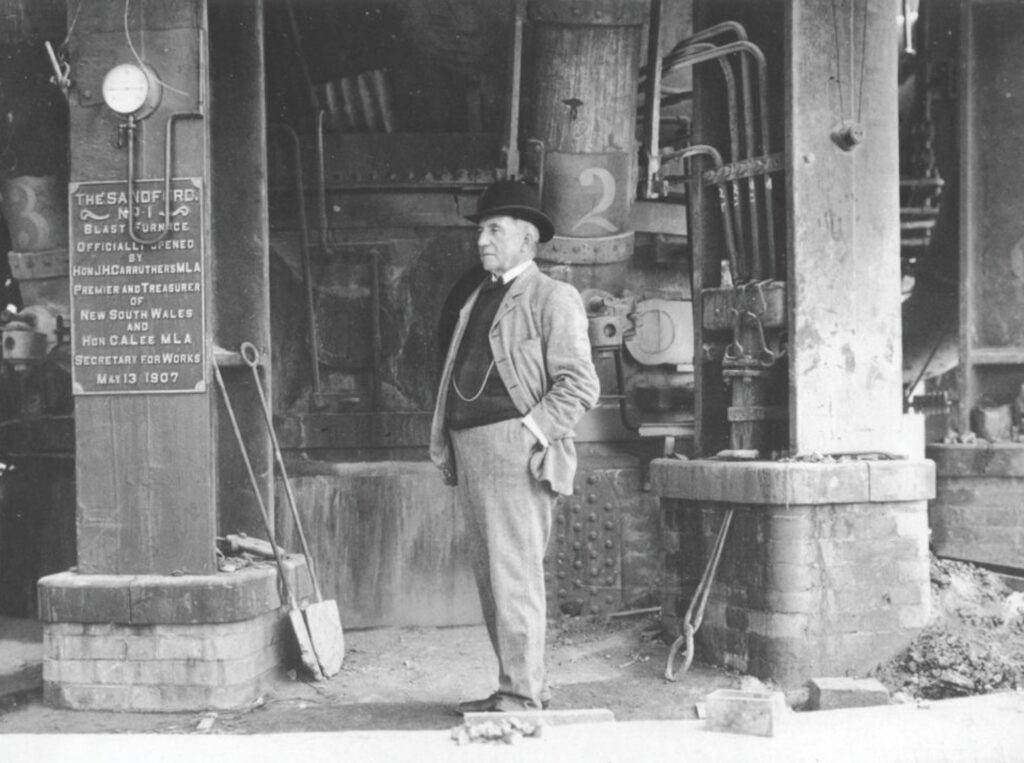

In 1907, a decision was made to establish a factory to manufacture small arms in Australia. Several sites vied for the location of this factory in the years leading up to the decision. The front-runner was Lithgow. The Progress Association encouraged former coal miner, local Federal member and Minister for Defence, Joseph Cooke (who was later to become Prime Minister in 1913-14), to lobby hard for Lithgow as the site of a new factory. But it was the owner of Lithgow’s Eskbank Ironworks, William Sanford, more than anyone else, who helped secure Lithgow as the site for the small arms factory. In 1904, he wrote to the Sydney Daily Telegraph offering the following if the Defence Department selected Lithgow as a site for small arms manufacture: a five-acre lease to the Commonwealth, coal at five shillings per tonne, production of suitable steel from his ironworks, and a rail siding at his expense.

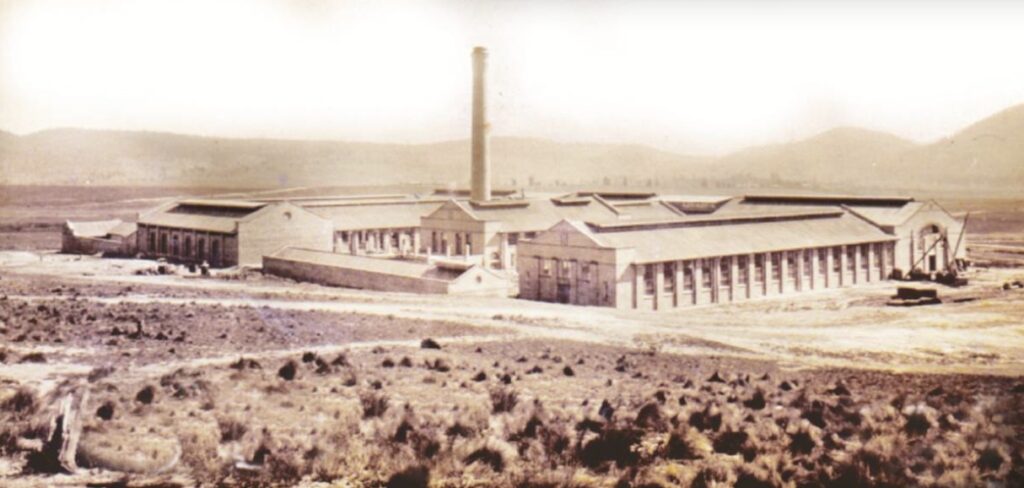

In 1908, the land was purchased in Lithgow, and Lord Kitchener inspected the site of the factory in January 1910. The Engineer-in-charge, William Clarkson, who concurrently led the team to establish the Royal Australian Navy, investigated arms manufacture in the United Kingdom, Europe, United States of America and Canada. His report and specifications led to tenders for the supply of a complete plant to make small arms and accoutrements in Australia. The rifle to be manufactured was the SMLE, the standard military weapon of the British and Empire forces.

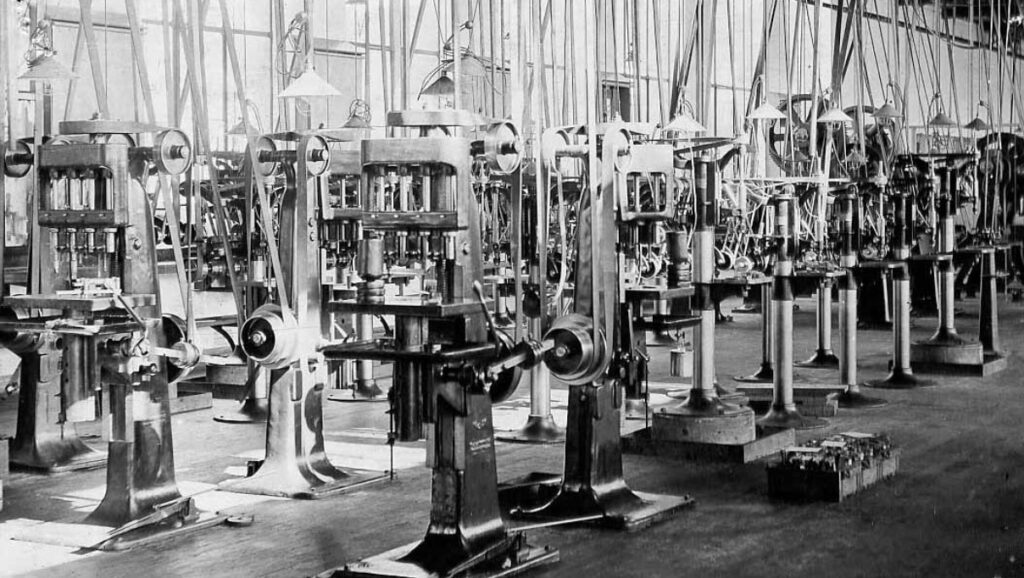

American machine tool company Pratt and Whitney won the tender, but the decision was controversial, particular as they didn’t make firearms. Many expressed doubts about their ability to manufacture a rifle to British standards with foreign machines. Instead, they made machine tools producing any component requiring repetitive precision manufacture or what we now know as mass production, the first company to do so in Australia. Clarkson believed this was critical, and the government agreed. A new factory was built and completed in 1912.

Between July 1913 and July 1914, just before the outbreak of WWI and continued unrest amongst nations, only 4,800 rifles were made and delivered to the army, hardly enough to defend the country. By the time Germany declared war on France on 3 August 1914, the Lithgow small arms factory (LSAF) was producing bayonets, rifles and charger clips. The factory, however, had to increase production substantially, and the search for raw materials and skilled men began in earnest. A second shift was introduced to cope with the doubling and a further re-doubling in demand.

At the time, Lithgow was unsewered, roads were dirt, and public transport was non-existent. The shortage of accommodation, combined with long cold winters, meant appalling conditions for the workers. In addition, while almost 100,000 rifles and accessories were produced per year during wartime, the factory was plagued with complaints about the quality of the rifles produced.

After the war, demand dramatically dropped, and being a government factory, it could not take on other commercial work to save jobs. The government, however, chose not to close the factory and insisted on a skeletal workforce to maintain capability and preserve skills in readiness for a quick ramp up if needed.

Timber rifle furniture

The general history of the Enfields is all about the metalwork, but not a lot is known about the wooden furniture, the group name covering the individual portions known as the stock (or fore-end), butt and handguard.

The army rifle had to be well built and sturdily made to withstand rough use. The butt and stock needed to hold their shape, not warp and split, and had to partially absorb the recoil, with the butt transmitting that recoil to the shoulder. The stock and handguard provided a suitable grip and insulated the hands against burning by the barrel when the rifle was used for rapid-fire. The butt also had to be strong enough to resist breakage when used as a club. In Europe and America, walnut was traditionally used for rifle furniture. It was favoured due to its mechanical properties, stability, strength, density, and it could be easily worked.

Australia had no true walnut timber anywhere in its vast forested areas. So, they were forced to look elsewhere for alternatives. While they did that, the early operation of the LSAF relied entirely on imported walnut, mainly from Italy but also from England. Studies to identify and test a small amount of Australian timbers began in 1907 in England, in parallel with planning for the LSAF, and ran until 1914. Three species from New South Wales were sent – maidens blush (Sloanea australis), coachwood or Dorrigo pine (Ceratopetalum apetalum) and white beech (Gmelina leichardtii).

Tenders were also called to supply small quantities of Australian timbers for testing in 1910. Seven Australian companies tendered nine species. Still, at least two species were rejected, including myrtle (Nothofagus cunnimghamii), which failed an inspection on the wharf, and leatherwood (Eucryphia lucida), both from Tasmania. Queensland walnut (Endiandra palmerstonii) and Moreton Bay chestnut or black bean (Castanospermum australe) were the most expensive in the tendered prices.

These timber trials soon identified a critical difference between British and Australian test stock sets – rifle weight. The blush tulip oak, booyong or crowsfoot elm (Argyrodendron trifoliolatum) gave a rifle weight more than the imported walnut stocked sample rifles and nearly a pound more than the lightest stock set made of Queensland maple (Flindersia brayleyana).

In November 1913, the army received rifles to evaluate the rifle function and performance of local timber. Two sets of rifles stocked with Queensland maple were made, and the saw rifle accuracy was rated highly, as was the overall performance.

The trial of Australian timbers was reported to Federal Parliament in May 1914. The report covered 15 species which were each seasoned and then machined for comparison to the machining properties of walnut. The report recommended Queensland maple as the best option. Most other species were rejected because the weight was significantly higher than walnut. In the case of the softer species, rejection was due to a tendency to tear during machining tests.

The report noted that the more denser hardwood Australian species were harder to cut than imported walnut, were harder on the cutters and made the machines more challenging to operate. They may have been tougher than walnut but were not suited to the stock making machines installed in the factory. In the end, Queensland maple, coachwood, and myrtle (in that order) were nominated as the most promising for future investigation to replace imported timber.

The LSAF has on display a set of nine SMLE rifles stocked in the following timbers – Queensland walnut, black bean, red carabeen (Geissois benthamii), myrtle, Queensland maple, a birch sp. from New Zealand, blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), Queensland crowsfoot elm and coachwood. It is believed that these rifles were part of the bushweek exhibition held in Sydney Town Hall for peace celebrations marking the end of WWI. The rifles are complete with bayonets and matching timber grips.

Before the timber could be fashioned in the factory, it had to undergo at least three months of air drying and then steam dried in kilns and conditioned in indoor sheds. The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research established elaborate drying yards for this purpose.

By November 1916, the LSAF factory faced an acute shortage of walnut imported from Britain. It was widely believed that walnut supplies were deliberately withheld for English needs. In April 1917, the Commonwealth Gazette showed eight companies received orders to supply local unseasoned Queensland maple, enough to make more than 17,000 rifles once they were seasoned.

Until the early 1940s, Queensland maple superseded walnut as the timber for rifle furniture. After that, there was some experimenting with coachwood. It was first identified as a promising material for firearms woodwork in 1895 and was used on some early sporting rifles and sold by gunsmith James Rosier in his Melbourne shop. In November 1927, Wallis Bros Limited advertised for 66,100 super feet of coachwood, enough to make 9,000 SMLE rifles.

The production of rifles at the LSAF dramatically increased after WWII was declared. By this time, Queensland maple was difficult to source as the rainforests in northern Queensland were cut out, despite new areas being opened. The District Forester at Atherton, James Dawson, was given the herculean task of supplying increased amounts of Queensland maple for the LSAF and the Indian Government. In the first year of the war, over 50 million super feet of timber were harvested from the rainforests of North Queensland. Over the years 1939-42, an average of eight million super feet of maple logs were harvested each year.

Not surprisingly, accessible stands of maple ran out early in the war years. National Security Regulations on 28 January 1942 restricted the use of timber for war needs to fulfil the national interest. It included the high-quality coachwood to be exclusively used in the manufacture of plywood for mosquito bombers and rifle stocks. Consequently, foresters were forced to oversee a dramatic increase in rainforest extraction during the war years.

In New South Wales, apart from the total exploitation of red cedar stands in the early years of settlement, logging in rainforests was mainly confined to hoop pine areas within the dry rainforest. However, with the development of mechanised equipment in the mid to late 1930s, the economic accessibility to these forests improved. As a result, and combined with the depletion of hoop pine, demand for other brushwood species such as coachwood, and the utilisation of other softwoods as substitutes for traditional imports during the war, led to a considerable increase in logging of rainforests.

Continued demand after the war

At the end of WWII, the return of soldiers helped precipitate a building boom. This led to a continued demand for timber at very high levels. Foresters were essentially directed to overcut forests to re-establish a timber industry and meet a great need for housing. Brushwood timbers, particularly coachwood, were favoured for furniture and cabinet manufacture.

While foresters saw this boom period as a short term policy to meet the nation’s needs, they believed any overcutting could be clawed back through reductions in quotas. In 1953, the first attempt occurred when the basis for allocating supplies to the timber industry was changed from rights to all wood on a particular area to an allocation of a specific volume. Unfortunately, foresters had to base the new allocations on mill log intake in the proceeding boom years, not the yield capacity of the forest. Consequently, overcutting continued.

It is a credit the New South Wales Forestry Commission did initiate research into the regeneration of logged virgin rainforests in the early 1950s and 60s. However, aware that the level of logging was unsustainable, their study on warm temperate rainforest dominated by coachwood showed that the recovery after light logging was poor due to crown dieback of the remaining trees. It led to a “fifty per cent canopy retention” cutting practice in the sub-tropical rainforests. Still, even this system could not provide enough timber to meet current mill quotas in perpetuity.

Greater public awareness and an ugly protests and threats

The 1970s saw a greater awareness of continued logging in rainforests by the public. The single-tree selection system was compared in a similar vein to the massive exploitation and clearing of tropical rainforests in other countries. The “fatal tendency to rhetorical exuberance” was first evident in the Border Ranges that adjoined the Lamington National Park on the other side of the state boundary. Individual concerns about logging spread to many people in the region and onto the bureaucracy and political sphere. Because of this, the state government commissioned a report from the State Pollution Control Commission on future land use. They offered several options ranging from complete preservation to logging up to utilisation limits. The government decided to reserve a strip along the border as a national park, allow temporary logging of a flora reserve, compensate a local sawmiller for forgoing logging quotas and start a coniferous planting program.

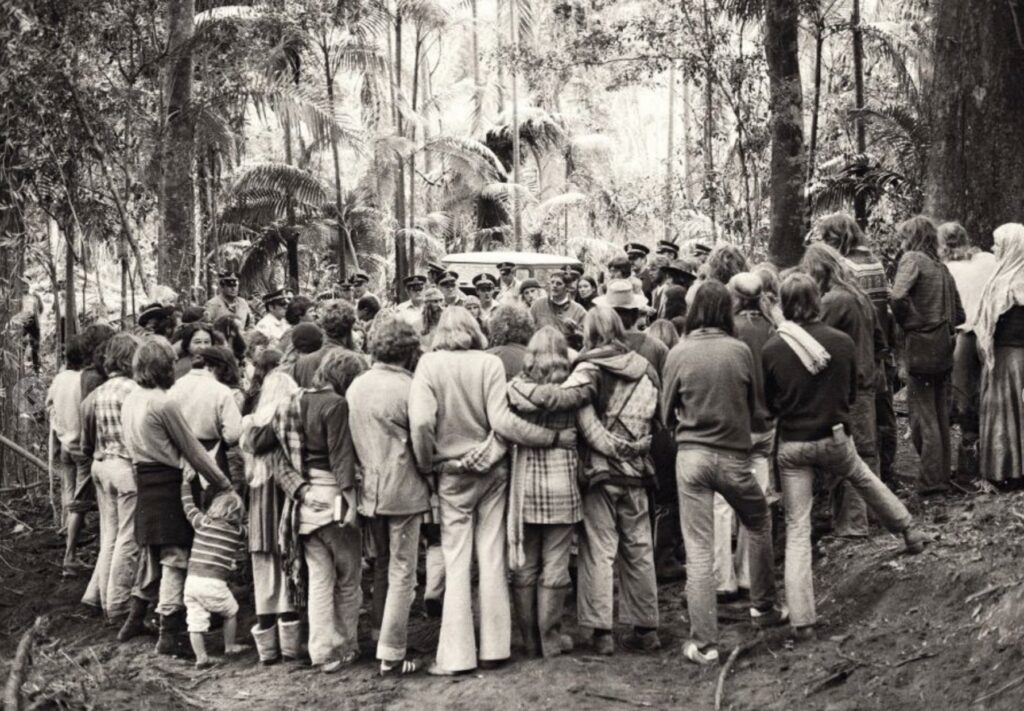

Planned logging of rainforest and hardwood in the Terania Creek catchment within state forests of the Nightcap Range in early 1975 went quickly from a local consultation phase to a full-blown forest protest. During the 1970s, the availability of cheap ex-dairy farm land and an agreeable climate attracted people to the area who sought a different lifestyle and who had very different value judgements.

These people mobilised their efforts into what they claim were non-violent direct-action strategies. Their intention may have been a peaceful protest, but their actions showed a more sinister role. For example, Hurford’s Hardwood sawmill at South Lismore was burnt to the ground during the protests, despite the company having nothing to do with logging in Terania Creek. In addition, employees of the Standard Sawmilling Company, who held the licence to harvest at Terania Creek, required police protection after some received phone calls saying their wives would get raped and their kids would not come home from school. Protesters also sabotaged logging machinery, and loggers say they received death threats.

The government held a public judicial review of the environmental factors associated with the proposed logging. This inquiry began in December 1979, and in October 1982, the New South Wales Premier, Neville Wran, made the historic “rainforest decision” to remove 100,000 hectares of forest from timber production. The problem was it included a substantial area of regrowth hardwood forests which impacted on the saw milling and timber industry in northern NSW for many years to come.

Conclusion

After the battles on the low veldt of South Africa, Australia saw a need to manufacture its arms to better equip its infantry forces in wartime. It included a need to use indigenous timber species most suited for rifle furniture. Suitable timbers were found in our subtropical and warm temperate rainforests in New South Wales and Queensland. Lamentably, demand for these timbers led to overcutting of the rainforests and was a constant concern for the foresters. They thought they could right the situation in the fullness of time.

Unfortunately, this situation was used by critics of professional forest management and led to direct action against the harvesting of rainforests. Having short memories, the activists associated with the forest protests of the late 1970s, and their supporters, argue the legacy of Terania Creek was a watershed moment in Australia’s environmental movement, and the first-time people physically defended a natural resource in Australia.

Foresters see the rainforests in both New South Wales and Queensland in a different light. The brushwood timbers such as Queensland maple and coachwood were a vital resource for our armed forces to defeat the brutal German and Japanese regimes and help the Allies maintain the freedoms and democracy that we enjoy today. They also provided the much-needed renewable resource that helped rebuild the nation after the devastating world war. In utilising the timber from the rainforest, foresters developed silvicultural systems to ensure the forests were maintained in perpetuity. But unfortunately, it was political imperatives, and not science, that prevented them from achieving that aim.