“But there is a sad symbolism in the tragedy of the burning bush capital, for Canberra was not merely sited in the political middle ground between Sydney and Melbourne but in an environmental middle ground between two Australia’s: that of the bush and that of the metropolis. When slammed together, the matter and anti-matter of Australian ecology are likely to explode. They are doing so more and more frequently and with great ferocity”. Stephen Pyne, The Australian, 20 January 2003.

“I believe this fire and this disaster was conceived 15 years ago and birthed yesterday”. Val Jeffreys, 19 January 2003.

Introduction

Weather conditions over the Brindabella Ranges to the west of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) started relatively mildly in January 2003 after a dry year. However, temperatures quickly rose to mid-30 degree Celsius at the end of the first week. As a result, the ACT Emergency Services Bureau (ESB) declared total fire ban days for 7 and 8 January. The Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) for 8 January was Very High at 45, even though predictions were that the fire weather would be less severe.

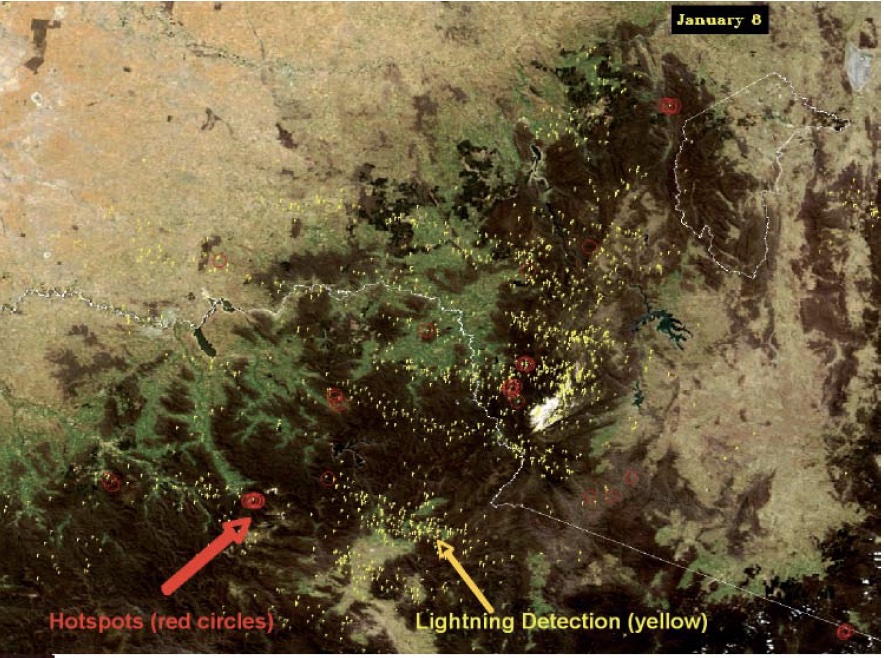

All fire towers in the ACT were manned. On 8 January, at about 3:30 pm, an electrical storm occurred across north-eastern Victoria, southern New South Wales and ACT. There were accompanying lightning strikes in a north-south line along the Brindabella Ranges. As a result, several fires were ignited in the Brindabella National Park in New South Wales (NSW) and Namadji National Park in the ACT.

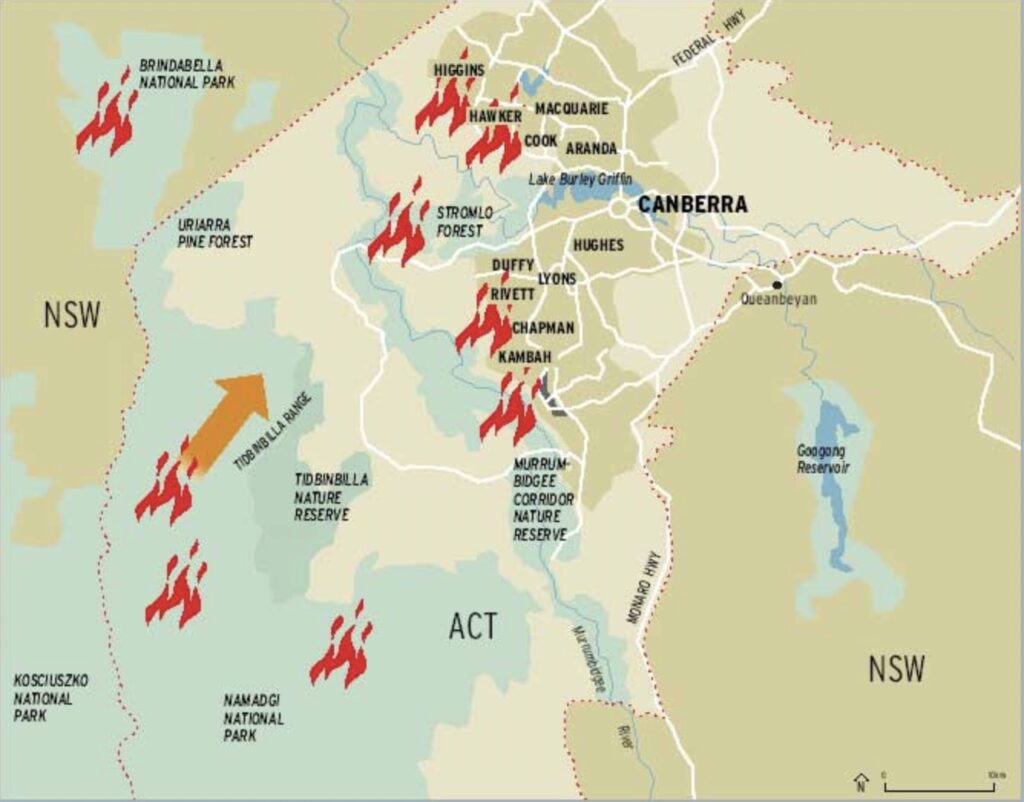

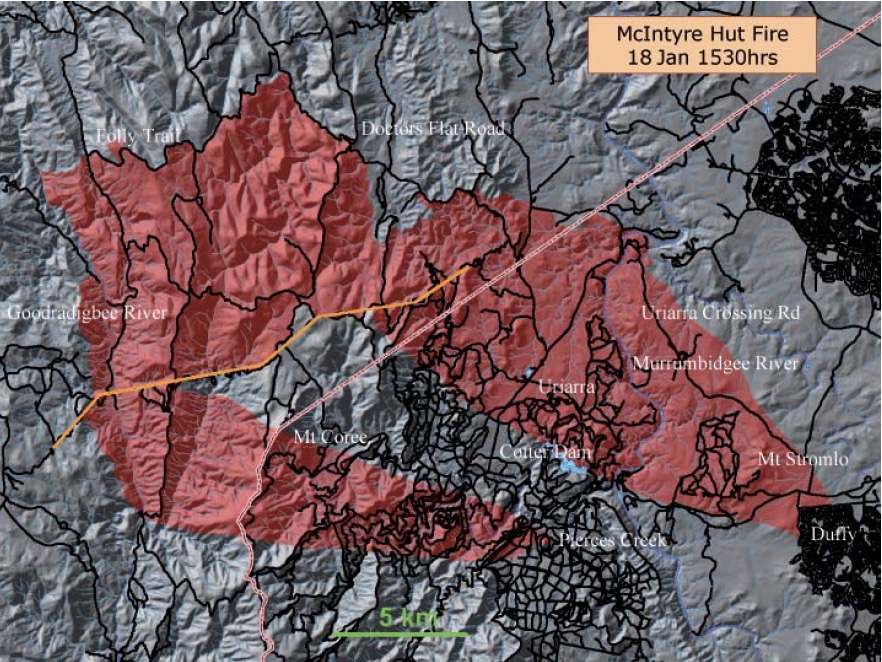

Ten days later, four fires known as the McIntyres Hut fire in the Brindabella National Park, and the Bendora, Stockyard Spur, and Mount Gingera fires in the Namadgi National Park coalesced under extreme fire weather conditions and burnt out of control into the south-western suburbs of Australia’s capital city.

The firestorm killed four people and destroyed 487 homes and 23 commercial and government premises. A further 435 people were injured, some with horrific burns, and 215 homes and buildings were damaged. In addition, the fires burnt out the renowned Mount Stromlo Observatory. Over 60 per cent of the ACT’s pine forest estate was destroyed. The burnt plantations included all of Pierce’s Creek, Uriarra and Stromlo Forests. The latter had existed on the western urban interface of Canberra since the 1920s and, as a result, was part of Australia’s “Bush Capital” fabric.

In total, the fires burnt nearly 160,000 hectares and almost 70 per cent of the ACT.

According to retired CSIRO research scientist and international expert on bushfire behaviour and management, Dr Phil Cheney:

“The fact that bushfires burnt into the urban area under extreme conditions did not reflect a failure of fuel management on the urban interface but rather a failure of fuel management in the forest area”.

Heavy fuels and lack of access hindered suppression efforts early in the development of the fires. They contributed to the fires burning a large area before the onset of extreme fire weather that drove them to Canberra.

This case study looks at the history of fires that have previously threatened Canberra, the decline in active fuel management and the inevitable consequence that culminated in a firestorm in January 2003. After many lessons, an adequate fire management system was developed surrounding the Bush Capital. However, from the 1990s, it was gradually dismantled in favour of an emergency response to dealing with fires and little fire preparation. Given the predictable outcome, it begs the question – why are lessons learnt so easily forgotten and ignored?

Analysis of the “Canberra problem” – the vulnerable western flank

“Government managers are not measuring up to the task of bushfire management. These days it’s about suppression, not prevention. The suppression industry thrives on fires. Big fires.” Ron McLeod

The ACT is a self-governing territory surrounded by the state of NSW. Immediately to the west of the city of Canberra is a vast contiguous area of forests, woodlands and grazing areas that extend deep into NSW, some of it very rugged and remote.

The fire risk situation around Canberra represents the ideal fire conundrum not only in Australia but around the world. A new reality has set in and according to Cheney:

“…almost everywhere in places with a similar climate, where urban development is expanding, and in affluent communities where attitudes to fire, and to fire prevention and mitigation, are changing”.

What eastern Australia has experienced in the last 30 years with extensive and damaging bushfires personifies the old saying that lessons are hard-won but are quickly forgotten. The lessons started not long after the establishment of a garden city in 1913 as the nation’s capital by Lady Denman on the treeless plains of the Molonglo and in the shadows of the forested Brindabella Ranges.

But nearly a century later, those lessons were all forgotten. Instead, it culminated in what many locals and fire experts had predicted would happen – a terrifying firestorm converging on the suburbs of the city that make up the interface with the bush.

The large contiguous area of forested land to the west of Canberra called the Brindabella Ranges is located at the northern tip of the Australian Alps region. When Canberra was proclaimed, the Cotter River catchment within the ACT was set aside to supply water for the new city under the management of ACT Forests.

The value of the Cotter River and its catchment was a major reason for the siting of Canberra to secure a stable and clean water source.

Canberra rapidly grew from the 1950s to the 1970s. With it came a recognition of the rugged southern region of the ACT and agitation for the area to be given national park status. The valleys were under leasehold or freehold and were used for grazing. This meant sheep ate down grassy pastures in the lead-up to summer. The high country remained uncommitted crown land. The activities of an initial lobby group led to the formation of the National Parks Association of the ACT (NPA) in 1960. They campaigned to establish Gudgenby as the first reserve in the ACT under the slogan “A National Park for the National Capital”. There was little political support for a national park at the time. However, after persistent representations by the NPA, the Gudgenby Nature Reserve was proclaimed in 1978.

Newly appointed Minister for the Territories and Local Government, Tom Uren, was shown the proposed national park with its beautiful mountains and valleys in 1983. The next year, the Cotter River catchment was combined with Gudgenby Nature Reserve to form Namadgi National Park, administered by the ACT Parks and Conservation Service. The south-west corner of Namadgi National Park was declared a Wilderness in December 1989. The northern Brindabella Ranges were included in the Namadgi National Park in 1991.

Immediately west of the border in NSW is the Brindabella National Park, created in 1996 and Bimberi Nature Reserve, both managed by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

After all those new dedications, the farmlands became reserves and grazing was withdrawn. As Canberra expanded to the south and west, the new urban development acted as a buffer, as there was little fuel in the gardens and parkland reserves. However, residents soon expanded their gardens onto public land and planted trees on the previously cleared strips. The western expansion stopped when the suburbs hit the maturing pine plantations and hilly bushland reserves.

Before the nation’s capital was created, many fires occurred in the Brindabellas and Namadgi forests and woodlands.

Dendrochronological studies reveal fires as far back as 1739. For example, in January 1858, bushfires raged through the country between Ginninderra and Duntroon:

“The whole country for miles around has been laid waste by the recent destructive and calamitous bushfires, and great will be the loss and deprivation to many of our settlers from the burning of their crops, the perishing of every morsel of feed for their horses and cattle, and the destruction to all kinds of property”.

During European times, fire was a constant; but it was used in a more controlled way. Farmers burnt stubble before sowing new crops. Graziers regularly burned the dry foothill forests and the Cotter valley to regenerate native grasses, while the distant and remote forest areas were left to their own devices. Residents in rural areas always burnt firebreaks around their homes at the start of summer. Consequently, even though there were wildfires in 1862, 1869, 1888 and the Yarralumla fire of December 1903, they were relatively small and did little damage. However, during a sweltering summer, a destructive bushfire swept through the grass country at Wallaroo and Ginninderra areas on New Year’s Day 1905, killing over 300 sheep.

The first Bushfire Brigades were established in 1903, and after the 1905 fires, public meetings were held to discuss bushfire prevention and suppression. In October 1915, the Federal Territory Bush Fire Association was created to coordinate firefighting efforts and implement measures to protect against fires under structured arrangements. Fire districts were created, each run by an elected Executive Officer.

The first bad fire season for the fledgling capital city was December 1918, when a fire smouldering in the rough country south of Mount Coree flared up on “Black Saturday” and jumped the Murrumbidgee River. An overnight easterly allowed firefighters to bring the fire under control.

In January 1926, dense smoke blanketed the emerging city for a week as fires burnt on a five-mile front west of the Murrumbidgee River in the Namadgi and Tidbinbilla area. The fires began in the Cotter catchment area in woodland, which carried a thick cover of dead tea trees and threatened Mount Stromlo pine plantations and the Observatory. That summer, immense damage was reported between Canberra and Albury by a chain of fires which ravaged nearly 200,000 acres of grass and timber country.

The Brindabella Mountains suffered major fires under extreme weather in December 1938 and January 1939. On 15 January, a fire which originated in the Goodradigbee River valley on the western side of the Brindabella Ranges went within three miles of the city. The saving grace was extensive areas of recently burnt forest in the Cotter River valley and heavily grazed grasslands on the city’s western edge. Although burning firebrands travelled 15 kilometres downwind from the Brindabellas towards Canberra, they could only ignite a few fires in bushland areas near Tharwa and Williamsdale.

In 1952, Canberrans were threatened again as fires, driven by hot north-west winds, swept overgrazed pastures of the Red Hill reserve and the newly developed Federal Golf Course. They reached the Tindery Ranges in a few hours, 30 kilometres south of Queanbeyan.

Another fire, started by lightning near Huntley, burnt through pine forests destroying the Mount Stromlo Observatory. It was contained when it came out into the grasslands. Luckily, neither fire affected suburban Canberra but burnt grazing lands that are now Duffy, Chapman, Deakin and Yarralumla. These fires managed to enter the consciousness of the city residents and influenced fire policy at the time.

Following the 1939 fires and subsequent inquiry, the ACT Bushfire Council was established, which determined the approach to bushfire management policy and operations in the ACT for the next 50 years. It was mainly staffed and manned by the Forests Branch within the Department of the Capital Territory. Between 1944 and 1996, the ACT leased an area in NSW immediately adjacent to its north-west border. It was managed as a buffer strip to reduce the threat of fires originating in the Goodradigbee River valley.

The graziers regularly burnt the bush, and this was combined with unofficial firing by rangers since 1929 to protect the hardwood timber resource and conifer plantations. The use of the Brindabella Ranges changed in 1952-1956 when the forestry burning ceased, and grazier leases were withdrawn. Dendrochronological work by botanist John Banks shows a dramatic decline in the number of fires, with only two fires at his sampling sites.

Alan McArthur was recognised as the “father of bushfire science” in Australia. Based in Canberra, he conducted experimental burns on the foothills of Black Mountain and in the headwaters of Blundells and Lees Creek between Picadilly Circus and Bulls Head in the Brindabella Ranges to collect data on fire behaviour. He advocated prescribed burning of ACT’s forests for fuel reduction to mitigate future bushfire damage. Every autumn burning off occurred in the surrounding forests and woodlands, and the city residents were unconcerned about the smoke.

The advent of aerial ignition in the mountainous Brindabella Ranges in 1967 increased broad-acre fuel reduction, although each year, the area burnt varied. For example, in 1976-77, around 20,000 hectares were burnt mainly in the Lease Area, with a selective burning program in the fire-prone areas of Cotter Catchment.

Meanwhile, the Bushfire Council and ACT Forests conducted regular burn-offs on the lease. The lease initially comprised 21,500 hectares but was reduced to 8,300 hectares in 1988. It was terminated in 1996 with the declaration of Brindabella National Park. As a result, prescribed burns were no longer carried out, according to David Ferry, a former ACT Forests employee, Canberran of the Year and National Fire Medal holder. The role of the lease was replaced by the Cross Border Agreement on Fire Management and Suppression between the ACT Bushfire Service and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service which focuses on cooperative firefighting arrangements and only makes general references to prescribed burns.

Canberra’s demographics changed to city-bred people who knew nothing about the threat of intense fire on their doorstep. Some large bushfires occurred in and around the ACT between 1960 and 1990. In 1965, a fire started north of Goulburn and burnt to the coast near Jervis Bay in a day. On the same day, a fire burnt across Kosciusko National Park from the Tumut River to Eucumbene Dam. While Canberra was in between these fires, none threatened the city.

On 21 December 1972, a fire started just before 3 pm off Warks Road near Bulls Head in the Brindabellas on a south-easterly aspect in 1926 alpine ash regrowth under extreme fire weather conditions. A light fire fighting unit failed to stop the spread of the fire. Bulldozers arrived around 6 pm and directly attacked the fire on the western and eastern flanks. Hand-tool attack supplemented by some back burning after midnight contained the fire by 9 am the next morning. The fire ground was successfully patrolled for three weeks to prevent any outbreaks. According to Cheney, competent and experienced foremen and bulldozer operators at the fire meant it was controlled during periods of very high to extreme fire danger.

After the nature reserves and national parks were declared, fire management was recognised but addressed only at a strategic policy level, not on the ground. The 1986 Namadgi National Park management plan referred to fire management and recommended developing a fire management plan. A draft plan was prepared but not finalised. From 1982, there was a dramatic decrease in hazard reduction burning in the park. This was mainly due to a growing concern in the community about the environmental impacts of broad-acre burning and smoke issues, and the practice was discontinued. The NPA was very influential in that decision.

A combination of long-term drought, high summer temperatures and strong winds kept fires going in January and February 1983 in the mountains to the south of Canberra, where 80 per cent of the Gudgenby Nature Reserve and part of the Cotter River valley burnt. The sky was full of smoke daily as firefighters struggled to control the fires. The destructive nature of the fires made themselves very obvious to the residents of Canberra.

In early March 1985, during a particularly wet spring and dry summer, two fires started on the city’s eastern side and burnt towards Captains Flat. The rear flank of these fires burnt slowly against the westerly wind towards backyard fences in Hackett, Holt and Garran but gave little clue to the speed and intensity of the head fire that trapped and killed a firefighter at Burra. I arrived back at university in Canberra immediately after the fires and remembered seeing the blackened hills of Mount Ainslie, Black Mountain and Red Hill.

For the next 18 years, very few Canberrans were exposed to fire, either prescribed burns in autumn or destructive wildfires in dry summers. As a result, a sense of complacency grew, and so did the forest’s fuels.

Canberra is on an ideal pathway for intense wildfires. Prevailing hot north-westerly winds can carry fires that start in the rugged and remote forests immediately to the west of the city. To deal with this reality, the only way practical preventative measure available to humans is to manage the fuel levels. The firestorm that hit Canberra on 18 January 2003 was years in the making. However, Canberra can never avoid the prospect of not having a severe bushfire disaster if the surrounding forests continue to be managed by benign neglect and the fuel levels are not regularly reduced. According to Cheney:

“…the condition of the fuels adjacent to the urban areas of the ACT, setback distances from forest vegetation and the compact nature of ACT urban development provided Canberra with the safest interface of any city within the equivalent or higher rainfall zone anywhere in Australia”.

In 1994, Howard McBeth was tasked with reporting on the ACT Parks and Conservation Service’s capacity to manage its lands and reduce the threat of wildfires on the urban interface. The report was criticised for focusing on structural arrangements for fire suppression and thus outside its terms of reference. Despite this, it is a must-read for those keen to understand why the 2003 firestorm occurred. By ignoring the increasing fuel loads – loads that developed through years of neglect – McBeth predicted it would leave the city of Canberra vulnerable to a bushfire catastrophe on the scale seen in January 2003.

In recognition of poor fire management practices in the ACT, and following McBeth’s report the previous year, the newly elected Liberal Government formed a Bushfire Taskforce chaired by Graham Glenn to review ACT’s bushfire fuel management practices and recommend policies and procedures for the future. One of the recommendations was for the land management agencies to prioritise prescribed burning and bushfire safety for residents in high-risk areas and a requirement to prepare fuel management plans.

The Christmas fires of 2001 were a prelude to what could happen if preventative work and a proper, rapid response was not carried out. Fires to the west and north-west of Canberra on Christmas Eve were the largest faced by ACT emergency authorities since restructure in 1995. The Stromlo fire burnt 1,240 hectares, including 540 hectares of plantation at Greenhills in two days under the influence of very strong north-westerly winds. The bad weather made containment difficult where some places were burnt up to the urban fringe. The rapid establishment of a functioning incident management team was one of the factors which helped contain the fires late on the second day.

The Canberra fire problem is known and is a reality. But unfortunately, in the lead-up to January 2003, the threat of a major catastrophic wildfire descending on the suburbs of Canberra was ignored. Simply put, the history of bushfires in the ACT is evidence that a conflagration was inevitable if the fuel loads in the surrounding forests to the west were not managed and if fires were not attacked rapidly, contained and not left to smoulder.

The development of the firestorm

On January 8th 2003, a cold front with dry lightning storms caused more than 100 ignitions in forest and grasslands between Mt Buffalo in Victoria in the west and Captains Flat NSW in the east. Many in accessible areas were fought on the first night by crews and brought under control around midday the following day, including all the fires that started on state forest.

While many fires in grassland and open forests were quickly suppressed, by 10 January there were at least 40 fires burning in the high country of Victoria, New South Wales and the ACT. These fires put a huge strain on fire suppression resources and those not suppressed in the first week continued to burn until widespread rain in March. This blog will focus on the four fires surrounding the ACT that eventually coalesced and descended on the city on 18 January.

[Please note that Phil Cheney suggested the above map is inappropriate and misleading because the symbol of the source as exaggerated flames is misleading, and the location of the fires in the mountains is not precise. The direction of fire travel from the south-west is also wrong. While I accept his expert advice, I have decided to retain the map as I wanted a simple graphical representation of the fires for the readers without cluttering the blog with lots of maps that may be confusing. Please understand therefore, that the map above is not an accurate portrayal of the ignition points but merely a geographic guide to help the readers understand where they started in relation to Canberra].

Soon after the fires on 8 January were reported and investigated aerially, ESB dispatched fire crews to the Bendora and the Stockyard Creek Fires. No one was sent to the Mount Gingera fire because of its remoteness and since it was burning downhill, the threat appeared minimal.

At Stockyard Creek, the initial ground reconnaissance found that the fire trail leading to the ignition was overgrown and impassable to tankers. At the Bendora fire, the field fire boss made an initial reconnaissance and crews laid-out hose lines. However, the fire boss advised ESB that it was too dangerous to attack the fire at night and sought their advice. While other experienced fire fighters, such as the Director of ACT Forests, Tony Bartlett, told the ESB Operations Officer he was concerned about not employing an aggressive attack, a decision was quickly made not to directly attack the fires that night, due to the safety concerns of the firefighters. Fire crews were withdrawn until the next day.

Former Chief of Victorian Country Fire Authority, Trevor Roche, told the Coroner the field boss was not sufficiently experienced to recognise the ramifications of withdrawing from the fire. Instead of trying to contain the fire before the weather deteriorated, the control centre quickly supported the decision to withdraw. Cheney told the Coronial Inquiry, although firefighting was a dangerous business and firefighter safety must always be taken into account, threats to the safety of the wider community as a consequence of firefighters not taking action must also be considered. The reality facing an experienced fire fighter was the fire danger was low to moderate that night and the fire was extinguishable because the expected southerly change, which arrived at 9 pm, would limit the spread of the fire. However, because the fuel levels were high, the fire did continue to spread overnight in the heavier patches.

At the McLeod Inquiry, ACT Bushfire Management stated that they were confident the fires in the ACT would be extinguished in the first 48 hours, despite the bad weather conditions, based on prior experience. A common feature of highland fires is self-extinguishment overnight, particularly during the cooler easterly winds.

A similar decision was made for the McIntyre Hut fire in NSW after a westerly wind rapidly pushed the fire up a slope, quickly growing to 200 hectares and throwing several spot fires down wind. Direct attack options were deemed unviable because of the rapid spread and the time to deploy resources to the fire. However, a mild southerly wind change arrived and by 10 pm, the flames at the headfire were less than one metre.

Volunteer crews from the Mullion and Brindabella brigades were available and prepared to go out to the McIntyres Hut fire that night. According to Cheney, under competent and experienced supervision they may have been able to suppress one of the spot fires and part of the western perimeter of the fire and reduce the total area that needed to be burned out.

At the joint meeting that night between ACT and NSW firefighters, the Coronial inquiry heard evidence of a “recognition of the potential threat to Canberra”. As a result, arrangements were made to declare the McIntyre Hut fire a Section 44 emergency since the fire posed an immediate threat to the ACT pine forests adjacent to the Territory border east of the fire and resources from elsewhere could be sought. Yet Tony Bartlett, who attended the meeting, recalled a different version, saying assurances were made that the McIntyres Hut fire was not considered a threat to assets, despite knowledge of at least three significant spot fires ahead of the main fire, and it was 27 kilometres, as the crow flies, from Canberra’s western suburbs.

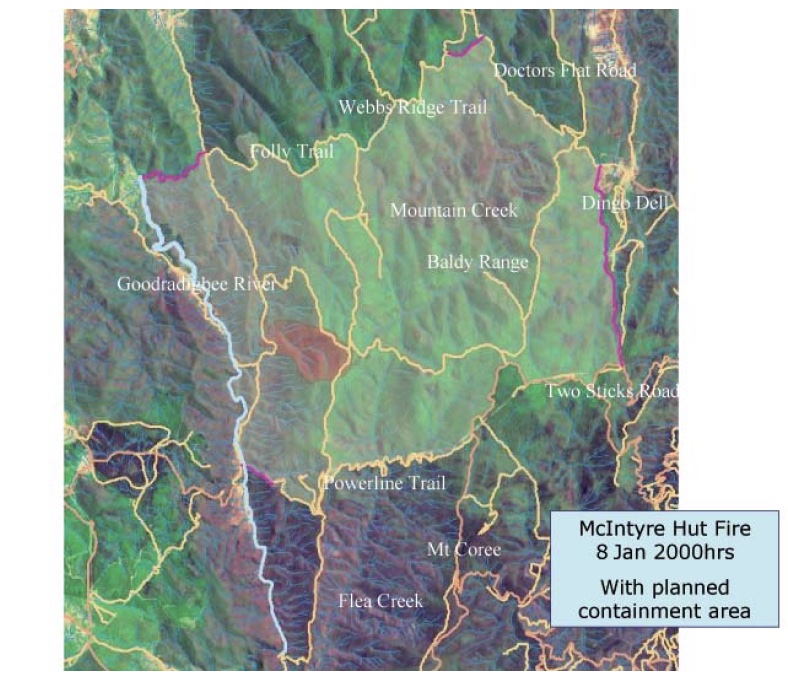

The strategy for McIntyres Hut fire was to indirectly attack using the Goodradigbee River to the west, the power line fire trial to the south, the unnamed fire break on the eastern perimeter of Brindabella National Park and Doctors Flat Road and Webbs Range trail to the north.

To carry out their plan successfully, the firefighters had to be confident they had enough days of favourable conditions before the weather deteriorated. The strategy was simple enough – use existing tracks with heavy machinery deployed to re-open some tracks and improve and clean up others. The original target set out in the first situation report aimed to complete the control lines the next day and backburn that evening to get the contained area burnt out and mopped up before the “next bad weather day”. This was certainly ambitious for such a large fire perimeter and at the Coronial inquiry it became evident that while all those involved in approving the strategy recognised it had to be implemented quickly, no specific time frame was developed for its completion.

Bartlett, in his other capacity as Deputy Chief Fire Control Officer, saw smoke plumes in the Brindabellas on his way to the city from Curtin and heard radio reports of smoke sightings. He told the meeting that night from what he saw there was a need to deploy additional resources as quickly as possible. He was concerned about the threat to the ACT pine plantations and offered his services. He was told ESB were not willing to deploy additional resources until reports from the fire ground were in and crucially he was told there was no role for him “until the numbers and locations of the fires had been confirmed”. There is no dispute that Bartlett was the most experienced fire fighter at the senior level of bureaucracy in the ACT at the time.

As the sun rose over the smoky ranges the following morning and the first firefighting crews arrived to mop up after the fires, they found they hadn’t self-extinguished. That sort of over confidence was critical. At no time was action taken to arrange additional machinery to put fire trails around the three ACT fires that morning, and less fire fighting resources turned up at the Bendora fire than the day before. The limited rake-hoe crew had to spend most of the morning putting in a line on the overgrown Bendora Break to allow a tanker to access the fire ground. A bulldozer was offered but would not arrive until first light the next day. Conditions deteriorated at around 4 pm and crews left the fires.

After assessing the Stockyard Spur fire on arrival, the field incident controller decided the best course of action was to construct a bare-earth mineral containment line by hand at the north-west flank supplemented by aerial water bombing. But this proved difficult and a dozer was requested. After a wind change and fire fighter fatigue, they left the fire just before 6 pm. Unfortunately, because suitable heavy machinery was not readily available, mechanical work could not start until 11 January.

A small number of fire fighters were dispatched to the Gingera fire around midday. They had to walk a considerable distance to reach the fire edge at 3:20 pm and reported the fire at 5 pm to be about five hectares with a flame height at half a metre. There was concern that the fire may cross Mt Franklin Road and move into the creek where there would be no way to stop it. Without a bulldozer available the only option was to carry out aerial water bombing which started at 6 pm. The crew stayed at the fire overnight watching it travel down the hill and edge up to Mt Franklin Road. Why they didn’t do any hand-trail work during the day is a mystery.

At the McIntyres Hut fire, despite agreeing on a strategy to enlarge the fire perimeter significantly that required work on containment lines, there were insufficient crews sent to the fire. Containment lines were not completed on various sectors, thus back burning could not commence as planned.

All the fires continued to grow during the day. Aircraft were used for water bombing. Experienced firefighters noticed “some unusual fire behaviour patterns occurring”, with a direct attack along some fire trails proving unsuccessful.

On 10 January, ACT fire crews turned up to the fires without any maps and no incident action plan. Because no-one was at the fires overnight, there was no handover intelligence. The Bendora fire boss was briefed about the weather, told the fire was about 80-90 hectares and instructed to contain the fire. Allocating resources, however, was a challenge when no-one knew the boundary of the fire.

The field incident controller at the Mount Gingera fire requested a small bulldozer to cut a trail around the relatively small perimeter to contain it. However this was immediately refused by the ESB control centre due apparently to environmental concerns. At 11:30 am the three RAFT crews, one tanker and one light unit were taken from this fire and deployed to the Bendora fire, leaving two tankers and one light unit. They managed to construct 200 metres of containment line in difficult terrain and dense vegetation and left at the end of the day. This was the only fire that offered a straight forward chance of control and containment. The fire size was estimated at 53 hectares that day. On 11 January the fire was 172 hectares.

Construction of containment lines continued at McIntyres Hut fire. At the incident management team meeting later that day, Bartlett again raised concerns about the potential threat to the ACT pine plantations because of the delay in commencing back burning. He was told back burning would commence along the southern perimeter the next day. He again offered ACT Forest crews to assist but was again refused.

Resources were kept at the other fires overnight for the first time to carry out back burning. It was not a change of conditions that led to that decision but a change in the method of firefighting to indirect attack and an experienced on-site incident controller was deployed.

However, that day, a golden opportunity to get on top of the fire was lost. With southerly winds blowing, there was the option to control the McIntyres Hut fire’s southern flank along the powerline. But fire controllers insisted on using a large helicopter to start lighting. There was also a delay in getting capsules to carry out the aerial backburning. Ultimately, they couldn’t get the helicopter and as a result, they subsequently lost the advantage of using the wind direction shift over the following few days.

The containment lines for the McIntyres Hut fire were not completed and ready by 11 January. As resources steadily grew to fight this fire, so did the control line’s length. The fire had grown to 1,100 hectares. A D9 dozer was deployed to establish a firebreak on the north-west edge of the Uriarra pine plantation close to the NSW-ACT border. This was a clear sign that the McIntyre fire posed a threat to the pine plantation after Bartlett clarified the potential development of the fire under bad weather, which could rapidly descend on Canberra.

By 12 January, even though conditions remained relatively mild with an FFDI of 15, the ACT fire authorities “reached the conclusion that the objectives it was seeking to achieve required capabilities that were not available locally”. In other words, the indirect strategy of falling back to containment lines and back burning, thus creating a much larger fire area, had stretched available resources. As a result, the ACT Chief Fire Control Officer advised NSW Rural Fire Service that the ACT would withdraw its resources from the McIntyres Hut fire to focus on their fires.

Easterly winds, common on summer afternoons in Canberra, blew the fire over the Brindabella range onto the western aspects towards Brindabella on 13 January. By 15 January, burning-out in the eastern aspects was almost complete but no operations had commenced in NSW.

The problem was exacerbated by the absence of existing tracks in the Upper Cotter Catchment and the adjoining Brindabella National Park. The fire trail networks in these areas, constructed many years ago, were closed and revegetated in the name of conservation. By this time, the options available to control the three fires for the ACT fire authorities were very limited.

On 15 January, ESB indicated that the Bendora fire was all but controlled. According to Cheney this was not true.

Map showing the development of the fires from 8 January 2003. By Drawn by Martyman in Illustrator using various sources including the McLeod Inquiry – Various sources including the McLeod Inquiry, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=823706

It wasn’t until 11:00 am on 17 January that aerial incendiaries were dropped within the McIntyres Hut containment lines under worsening weather conditions, with an FFDI Rating of Very High. Predictably, this operation had to stop due to high winds. That afternoon, the fire broke the containment lines in the south-east under strong north-westerly winds. The four, now large fires, made a significant run towards the outer suburbs of Canberra on the urban-bush interface.

Hell breaks loose on the 17 and 18 January

“They were told one point in time that they had 10 or 15 minutes, and then within one minute, the fire was upon them and had gone beyond them”. Police Superintendent Mark Johnson.

Initially, the winds on 17 January were light and variable but increased up to 35 kilometres an hour for most of the afternoon. As a result, the FFDI reached 50, which is Extreme. According to the weather forecast, it was the first of several successive days of severe fire weather.

The McIntyres Hut fire broke its tenuous containment lines due to spotting and was uncontained in bushland adjacent to the ACT border and headed east over the border. Significantly, the fire spotted over the Gooradigbee River and burnt slowly uphill against the wind. This new area of uncontained fire to the west of the main fire caused significant problems the next afternoon under the influence of strong north-westerly winds.

Up to 17 aircraft were trying to put the fires out without success. Unsuccessful attempts were made to re-establish containment lines around the Bendora fire, and the Stockyard fire moved into Tidbinbilla and Tharwa. Consequently, all firefighting resources were withdrawn from the fires. The Bendora fire crossed the Cotter River overnight. With the fires surrounding Canberra uncontained, the speed of their run towards the pine forests and the suburbs was alarming. Predictions of fire spread suggested that the fires could reach the city’s edge the next day.

A meeting that night changed the focus of fire fighting solely to property protection, including the protection of the pine plantations.

Saturday 18 January was a bad day. The forecast included a maximum temperature of 40 degrees and north-westerly winds of 35-45 kilometres per hour, gusting to 60. At first light, the McIntyres Hut fire was burning in the bush and heading towards the northern end of the Uriarra pine plantation. However, the uncontained fire on the western side of the Gooradigbee River spotted back across the river to the south of the control lines and raced uphill to Mt Coree.

The Bendora fire had been contained where it had burnt into private property in the Tidbinbilla valley. However, it was still burning uncontained to the west in Namadgi National Park and Pierce’s Creek pine plantation. The Stockyard Spur fire had made a major 15-kilometre run the previous afternoon from near Corrin Dam and was burning around Mt Tennant near Tharwa, south of Canberra.

By midday, the Bendora and Stockyard Spur fires were uncontrollable. Massive spotting occurred in the grassland. The Bendora fire spotted into the Bullen Range Nature Reserve. Shortly after, there was mass spotting over the Murrumbidgee River into grassland to the west of the southern Canberra suburbs.

The McIntyres Hut fire became active on its southern flank around 2 pm, enveloping Canberra in darkness. The fire spotted into grassland around Uriarra and then into the Uriarra pine plantation. Once it spotted over the Murrumbidgee River, it entered the Stromlo pine plantation and raced towards the other fires and the suburbs in Weston Creek at a forward rate of spread of 5.5 kilometres per hour. It was then sucked into the Bendora fire on either side, generating cyclonic-strength winds.

The fires hit the western suburbs in full force. McIntyres Hut fire reached Duffy at 3:15 pm. At that time, the FFDI was 102. Fire behaviour was ferocious and deadly in the grasslands and pine plantations.

The fires penetrated deep into suburbs, with many houses lost through ember attacks. The ferocity of the fires was compounded by a fire weather-generated tornado, which not only fanned the fire and spread embers but also caused extensive damage. In Chapman, numerous houses had roofs blown off before the they were burnt. The firestorm overwhelmed the fire agencies and residents. By this time, the fire authorities could do nothing to stop the blaze in the suburbs.

The fires affected 70 km of the urban edge of Canberra and 66 per cent of the land area of the ACT. Ninety-one per cent of Namadgi and 99 per cent of Tidbinbilla were burnt.

It was estimated that 95 per cent of the captive wildlife in Tidbinbilla, including species connected with captive breeding programs, were killed. In addition, about 66 per cent of ACT Forests’ plantations (16,770 hectares) were burnt in 24 hours, with an estimated $55 million worth of timber loss.

The aftermath – why weren’t previous warnings and lessons heeded?

“It’s like a war zone”. Chapman resident Steven Spencer quoted in the Canberra Times on 20 January 2003.

“It’s just human nature to conveniently forget what you should have learned and repeat your stupid behaviours“. Elliott Yeomans

Could the damage from the Canberra firestorm have been avoided?

I firmly believe that the disaster of January 2003 highlighted the lack of preparedness in the ACT community for a major bushfire. As urban development in the ACT grew, the attitudes to fire changed.

It is not acceptable to have a large contiguous area of mountainous and foothill country without any fuel reduction burning for over 20 years. Nor is it acceptable to not have a strategic network of properly maintained fire trails for access and use as fire control lines. And finally, firefighters must aggressively attack fires as soon as they are detected, and small and ground operations must continue into the night when conditions are most favourable for firefighting. It is also essential that bulldozers support ground crews, are on stand by, and are deployed as soon as possible to ensure new containment lines are constructed quickly, where required, to aid in containing the fires.

The emergency chiefs knew the problems they faced after the Christmas fires of 2001. The ACT Chief Fire Control Officer, Peter Lucas-Smith, conceded their focus solely on managing fuels at the urban interface was “probably only an entree to what’s potentially going to occur”. They had an immediate rethink about managing fuel loads by revising the Bushfire Management Plan which saw a strategy to bring back broad-scale fuel reduction burning in forested areas. It was noted that fuel loads in Namadgi National Park were at “maximum or equilibrium levels”. But it was too late after 30 years of neglect. If it were not for the 2001 fires, the 2003 firestorm would have burnt onto Black Mountain when the winds shifted from north-west to westerly and there would have been the same impact on the suburb of O’Connor as there was on Duffy. This just further highlights the importance of managing fuel loads.

That the Canberra firestorm was allowed to develop as it did, despite the accumulated wisdom of so many previous inquiries and reports, court cases, millions of dollars in research and training, and an investment across the country conducting many years of prescribed burning programs must surely indicate that the lessons of past disasters and the recommendations following them have been forgotten or denied. What is the point of holding inquiries unless the agreed recommendations and lessons are followed diligently?

Are the capabilities of the new emergency chiefs able to protect the Bush Capital if they choose to ignore, or not even study and know these hard-won lessons? And why was one of ACT’s most experienced firefighter shunned at the top level during the fires?

It is not a deliberate denial but a symptom of emergency managers not committed, long-term, to a dedicated role and changing cultures at every political election.

It is not as if 2003 was a new experience. The past lessons are well known. Their successes and messages should be permanently ingrained in all people associated with fighting fires and not overtaken by esoterical and untested ideology. At the Coronial inquiry, Cheney pointed out that the 1972 Pago fire started in a similar location to the Bendora fire and under similar weather conditions. The Pago fire was contained over a couple of days. The different response to the Bendora fire and its eventual tragic outcome reflected the operational and cultural changes that have happened with fire management over 30 years for the worse.

The removal of broad scale burning in favour of managing fuel at a micro level on the urban interface was futile because the condition of fuels adjacent to the urban areas, the setback distances and the compact nature of urban development made Canberra one of the safest urban-rural interface regions in the country. The fact that the 2003 fires burnt into the urban area was a failure to manage fires in forest areas, not a failure of fuel management at the interface. Indeed, this is the problem faced in similar areas around the country and for rural landholders that adding large areas of reserves managed under benign neglect.

The environmental protection priorities since the 1980s have led to large-scale neglect of bushfire preventative maintenance of forests, parks and adjacent rural areas. For example, the heavily influential NPA has many noble environmental ideals but no practical idea of implementing them that recognises the brutal reality that faces Canberra and its residents. While the NPA has always maintained they support prescribed burning, it comes with a caveat that it must be subservient to ecological considerations.

In 1980, they opposed the planned construction of new fire trails in the western area of Gatenby Nature Reserve, calling such proposals a “serious menace to the natural values of the Reserve…additional trails are unnecessary for fire management”. In commenting on a review of the Koscuisko National Park management plan in the same year, they questioned the necessity of broad area prescribed burning and argued for lightning fires to be allowed to burn. In response to the destructive fire in January 1983 in the Gatenby Nature Reserve, their “spiritual home”, they focussed on minimising damage after a fire started. No consideration was given to minimising the chance of fires ripping through the reserve in the first place. They also complained about the environmental impact of fire trials built or reopened during the fire to try and minimise the fire’s spread. However, they were silent on the ecological damage caused by the high-intensity fire.

The most devastating fire disasters in Australia’s history have occurred when the population, the government and the government agencies are unprepared. Sadly, the fire and emergency authorities displayed this by not warning or informing the public that the fires could converge on the suburbs of Canberra. A State of Emergency was not declared until 2:45 pm, moments before the first houses burnt in the outer suburb of Duffy. This was after residents were told until the morning of 18 January that the fires were under control.

For many years before 2003, rural landowners in the ACT and surrounding districts within NSW were outraged at the lack of fuel management and bushfire measures. As a result, fuel management was the primary focus of the McBeth and Glenn Reports and featured in several recommendations in the coroner’s and McLeod reports.

One of ACT’s most experienced firefighters, Chairman of the Bushfire Council for over 12 years and holder of the Australian Fire Service Medal, Val Jeffreys, was scathing in his submission to the inquiry claiming the fires were a “national disgrace”. He believed:

“…the fires were never under control and were never going to be controlled in the mountains once the non-existent initial attack failed”.

Part of the problem has been the hijacking of bushfire management strategies by green lobby groups that influence government policy decisions. Extreme conservationist concerns overrode operational recommendations and repeated warnings given to authorities. Based on fire experience dating back to the 1950s when he was the foundation member of the Tharwa Fire Brigade, Jeffreys claims his warnings were repeatedly ignored.

Where is the accountability?

“it is a miracle that no more than four people died …On the evidence before the inquiry, I conclude that the failure to warn the community – despite senior personnel of the Emergency Services Bureau having knowledge that the fires would burn into the suburbs – was a factor that exacerbated the property losses and resulted in panic and confusion throughout the affected suburbs on the day of the firestorm.” Maria Doogan’s letter to ACT Attorney-General.

Previous governments and bureaucracies have deliberately overlooked the real problems from past fire inquiries and committees. This is because they design inquiries to focus on process, not outcomes; on administration, not operations; and on response, not mitigation.

Regarding disasters and government agencies, accountability and transparency are not high priorities. Perhaps this is because of vested interests and self-interest, or maybe because accepting the truth leaves them exposed and liable to claims of mismanagement and negligence. That is what happened in the aftermath of the 2003 firestorm.

For example, landowners and insurance companies tried to sue the NSW Government in the ACT Supreme Court. Chief Justice Terrence Higgins found that the New South Wales Rural Fire Service were negligent in not aggressively attacking the McIntyres Hut fire early. Former NSW Rural Fire Service commissioner Phil Koperberg told the court that on 15 January, he was aware that the western suburbs of Canberra were threatened by extreme fire weather predicted for 18 January. He also said that he did not believe the fires could be suppressed before the onset of the extreme weather conditions. The plaintiffs argued that Koperberg did not immediately communicate the seriousness of the threat to landholders and Canberran householders. Sadly, under the NSW Rural Fires Act 1997, the Rural Fire Service and its officers are immune from liability, despite the court finding that they were guilty of gross negligence.

ACT’s Chief Minister and Attorney-General, John Stanhope, announced a coronial inquiry after the 2003 fires. He promised:

“It would leave no stone unturned in examining the actions of all agencies and emergency services management. There will be a close and uncompromising inquiry into every decision or action taken by everyone involved with the fire”.

Chief Coroner Maria Doogan’s Inquiry raised serious questions about the territory government’s response to the firestorm and lack of early warnings to residents. It could be argued Doogan met the brief set by Stanhope (see the final reports here and here).

Her counsel assisting, Lex Lasry QC, suggested the disaster may have been preventable, and it seemed the government was warned such a firestorm would occur. He added “that the firestorm’s severity and impact could have been mitigated”.

Doogan recommended criminal investigations of nine senior ACT bureaucrats following a series of “lethal acts and omissions” in the 2003 fire tornado. One glaring example was that no Incident Management Plan was prepared overnight for firefighters on 18 January, allegedly because no Incident Management Team was in place that night shift. Another was a failure to heed warnings from the Bureau of Meteorology of severe conditions for three days before 18 January. According to her, these senior officers did not treat the warnings with the gravity they should have.

However, after sitting for 86 days, producing 8,000 pages of transcript and costing $6 million, the inquiry was suspended for nearly a year when the accused bureaucrats, supported by the ACT Government, tried to disqualify Doogan due to a “reasonable apprehension of bias”.

It was claimed Doogan had “inappropriately or undisclosed” contact between herself and expert witnesses, and she refused to release experts’ documents. It was extraordinary that the government interfered in a judicial process. Under the Coroners Act 1997, the Coroner has powers to inform themself any way they see fit. They gather information, and if further legal action is required, it moves to a separate civil trial. However, according to Stanhope (one of those served notice by the coroner), who is a trained lawyer himself, the inquiry he called was not one to apportion blame, even though he told the media it would be an “…inquiry into every decision or action taken by everyone involved with the fire”.

But the government and the bureaucracy did not want that process to proceed, claiming the coroner favoured expert witnesses who were critical of the government. Doogan found public support, however, on the steps of the ACT Supreme Court, where placards such as “Let Maria fan the flames of honesty” were displayed.

The government hired a “Macquarie Street” legal team and spent $250,000 trying to sack Doogan. While the nine bureaucrats had every right to defend themselves and pursue legal action, it was questionable why taxpayers paid their legal fees. It was a different story for a group of fire victims who took the NSW Rural Fire Service to court but had to pay their own legal fees.

Ultimately, the full Supreme Court bench backed Doogan and deemed the evidence of “apprehension of bias” was trivial, and she remained as coroner on the inquiry.

Yet the government still managed to avoid any accountability for the disaster. When Stanhope was asked why the warning given to residents was so late, he glibly deflected, blamed others, and avoided any responsibility:

“There is a high level of bitterness within some of these people at the disaster, and that is reflected in a bitterness towards me”.

I struggled to find any public apology to the families who lost loved ones or had their houses burnt to the ground. He was wrong when he told the media the emergency services did all they could, but had no way of stopping the disaster. For a start, they should have insisted the fuel levels in the forests were properly managed prior to 2003.

There is an increasingly worrying trend across Australia where some government agencies are moving away from their duty of care responsibilities to the community. And they get away with it because philosophical and aesthetic objections to prescribed burning have influenced governments to abandon sustainable land management in favour of emergency life and property protection. Social and environmental disasters then become heroic triumphs for the government and the emergency agencies. But unfortunately, the advocates of these new policies also use exceptional climate and weather as excuses to cover unsustainable management practices.

It is appalling to witness the damage to ecosystems, rural assets, homes and life that occurred in the 2002-03 summer and subsequent years. You would think that after 51 fire inquiries and reports since 1939 and over 1,700 recommendations, governments and fire management agencies would be prepared and ably equipped to avoid the catastrophic fire events and losses on the scale of the 2003 Canberra firestorm. Unfortunately, by virtue of the bushfires size and destructive force, Australia has not moved forward regarding bushfire management since the disastrous fires of last century – it has instead gone backwards.

Some have argued that recommending prescribed burning doesn’t mean it can be implemented. They cite the recent decision by the Victorian government to remove an area target of annual prescribed burns that was formally implemented after the 2009 Black Saturday fires. But published and unpublished empirical evidence from foresters shows that an active annual broad-scale prescribed burning program is one of, if not the best, tool available to reduce the chance of mega-fires overwhelming settled areas.

The idea that prescribed burning is an environmental threat is fanciful. Studies of prescribed burning demonstrate that sensitive or threatened plants do not disappear. Unfortunately, no assessments are carried out on the consequences of not carrying out regular burning. A controlled and patchy light burn is not uniform and, unlike severe wildfires, does not cause structural changes to recovering vegetation and increases in fuel accumulation. Forest ecologist Vic Jurskis has studied the causes of tree and forest dieback around Australia. He states:

“…it is not well appreciated that fire exclusion and high intensity fire reinforce each other in a vicious circle of environmental decline”.

Cheney agrees and believes that extensive fires of high intensity, such as those of 2003, are unacceptable in ecological terms by causing a loss of diversity, and in social terms, through a loss of life and property. Furthermore, the widespread, high-intensity fires will not reduce unless we recognise the need for intensive fuel reduction programs. Based on seven inquiries since 1986 into aspects of the ACT emergency services, he predicted a conflagration of the type experienced in January 2003.

It was a brave decision not to aggressively attack the Namadgi fires early and try to contain them in 2003. However, to instead fall back to existing and newly constructed control lines and conduct a backburn was problematic given that Namadgi National Park had not seen a fire since a prescribed fire since 1979. This meant that a backburn had to be carried out in heavy fuel loads making the job very difficult when the weather conditions were not ideal. Added to firefighters’ woes, many of the tracks within the national park needed for control lines had been closed and revegetated.

The NPA, which spent many years lobbying politicians to reserve the forest areas surrounding the city into national parks and wilderness areas, and officers of ACT Parks and Conservation all expressed shock at the devastation of the 2003 fires. However, there was no sign of any self-examination by NPA in the aftermath of the fires. Rather than reconsider their policies that promoted a form of benign management and closure of tracks that were leading factors in the total blackout of the landscape, they were in full force advocating a “coordinated and collaborative response to bushfires”. However, they offered no practical ideas on how to prevent or minimise the damage of bushfires under extreme weather conditions in the first place.

Conclusion

It is now 20 years since the 2003 firestorm. Unfortunately, as time goes by, Canberrans again appear not to heed the lessons learnt from that catastrophe. For example, in the last five years, the area prescribed burnt (14,440 hectares) was less than half of what was achieved in the previous five years (30,261 hectares) and less than half of the area planned (31,349 hectares). According to the ACT Bushfire Council, the reasons for this “are not clear, but the trend is strong and suggests systemic factors may be involved”. In addition, the ACT Government recently cut the Parks and Conservation Service fire management budget by 13 per cent despite Canberra remaining vulnerable to bushfires from the west and north-west, which didn’t burn in the 2019-20 fires, and fuel levels are high and continue to build. This is deeply concerning for the residents on the western fringe of the city who could face a 2003 scenario again during the next drought conditions over summer.

We have a serious problem under the current fire management system followed in the states and territories. While the organisation command system under the Incident Control Management hierarchy has merits in trying to find order in a chaotic situation, a total dependence on its function after a fire starts has completely overridden the importance of adequately preparing for each fire season. Any errors or failure to follow previously successful fire management practices are quickly glossed over by blaming the fires on climate change rather than accepting responsibility for lives lost and houses destroyed and changing practices.

There are few extreme fire days each summer, but it is what happens, or doesn’t happen, in the lead-up to summer that determines whether a wildfire can be controlled, or an unmitigated disaster is experienced. It is too late to try and save assets and people after a fire starts in forests carrying very high fuel levels in the middle of summer.

High-intensity fires result from two factors operating together – predisposing drought with hot, dry weather and heavy fuels. A failure to manage the fuel levels in our forests inevitably leads to periodic large-scale fires across the landscape.

Practical land managers such as foresters understand that the bushfire problem can be dealt with through two main elements. One is to minimise the risks of fires starting and causing damage to assets and secondly, ensure the capability to suppress fires before threatened assets are burnt. The importance of aggressively attacking remote fires as soon as they are detected and having lighter fuel loads to do so are crucial in preventing the possibility of fires travelling a long way very quickly when severe weather conditions arrive.

The 2003 Canberra firestorm shows the folly of ignoring these two elements and what can happen so suddenly and quickly. Unfortunately, the community does not understand these factors. Many people deny that they are relevant. It is reflected in a lack of commitment to effective fire management at the Ministerial and agency level. And it shows a divided community, especially at the interface between urban and rural.

Stephen Pyne was right when he wrote that the symbolism of the tragic 2003 Canberra fires was the battle between the bush and the city at the interface, and the ferocity of the explosion reflects who was winning the fight. Cheney now believes Canberra is no longer the Bush Capital; it is now the Bushfire Capital.

Addendum

There were other inquiries associated with the broader 2002-2003 fires that occurred elsewhere in Australia. They also included an examination of the 2003 Canberra firestorm. The main one was the Federal Parliamentary Inquiry into the 2003 Australian Bushfires and its “A Nation Charred” report. It was significant that Gary Nairn chaired the inquiry as his electorate of Eden-Monaro was one of the most affected areas by the fires. It is considered the most comprehensive examination of all aspects of the bushfires that summer. The main evidence came from volunteer firefighters, local landholders and fire management experts who felt they were excluded from the state-based inquiries. However, government agencies were not allowed to participate in the inquiry by their State Premiers.

Instead, they set up another inquiry – the Council of Australian Governments National Inquiry into Bushfire Mitigation and Management headed by Emergency Chief Stuart Ellis. This inquiry gave a much lower emphasis on reducing dangerous fuel levels in favour of educating the public on how to live with bushfires so that state governments could continue to focus on emergency response and evacuation procedures when large fires occur instead of practising sustainable land management prior to each fire season.

The efficacy of their education programs is highly questionable as over 200 people have died and thousands of homes destroyed since their recommendations were put forward. Sadly, no one in authority is willing to accept responsibility for this failing and the disastrous fires will continue until the necessary and fundamental changes are made.

And finally some visual proof that nothing has changed since the 2003 firestorm. The photo below was taken in September 2020 facing south on Smokers Trail in Namadgi National Park. The Orreal fire burnt out 80 per cent of the park in January 2020. Note that above road the forest canopy is undamaged in that wildfire. That is because the fuel loads were reduced from a prescribed burn carried out in April 2019. Below the road shows there was a crown fire. Why, because the last burn in that area was the January 2003 bushfire, 17 years earlier.

You have written many articles on land and forest management.

This one is one of the best. I would urge anyone interested or involved in fire (mis) management to read this.

Great piece.

Fighting fires is like going to war.

You don’t win wars by taking a back footed approach, always get on the front foot and attack aggressively with intelligence, experience and a willingness to tough it out as your foundation.

Magnificent article, thanks Robert.

In Western Australia we at last have an agency who are doing their best (with grossly inadequate resources) to maintain a patchwork of light fuels through the forest zone in the south-west.

From what I can judge, WA is the leading bushfire management jurisdiction in the country, and the mitigation is politically supported.

However, this fine work is being confronted by a well-orchestrated campaign by a small group of academics from UWA, and Curtin and Murdoch Universities, to curtail, undermine, or stop the prescribed burning program.

They are, inevitably, supported by urban environmental activists and green politicians. If the government succumbs to this pressure, there is not doubt that “another Canberra” will be inevitable.

Thanks Robert, a good summary and commentary.

Just one suggestion, the comment by Phil Cheney on your map as misleading clearly refers to the earlier map of ignition points, not the map illustrating the development of fires from 8 January.

The map with graphics showing development of the 4 fires is accurate and very useful. The earlier map with the many fire icons is inconsistent, and I agree with Phil, it would improve this report if it was deleted or corrected.

Hi Peter

I checked my email correspondence with Phil and yes you are correct. I immediately thought he was referring to the map with graphics. It all makes sense now. I was determined to keep that graphics map in the blog as I thought it was a very useful illustration of the development of the fires.

Thank you for pointing this out and I have made the necessary change.

Yet another grim story about the total criminality of dumb bureaucrats and others who have “no skin in the game”, but who make sure that the decades of hard-won experience in bushfire management CANNOT be utilised today.

The list of bushfire Royal Commissions is too long already, yet it continues to get longer; NOBODY CARES!!!!!

Congratulations Robert – a well researched, well written and authoritative ‘essay’, if I can call it that.

The failure to learn from the past, to ignore the experiences of fire fighters and to ignore sound bushfire science (as opposed to the junk science that’s out there), is inexcusable and a dereliction of duty. But we see it time and time again.

Why? There are many reasons, but I think the root cause is lack of proactive, strong leadership. It takes all the qualities of leadership to plan and implement the key bushfire mitigation policies and strategies such as landscape prescribed burning of public lands, sensible urban planning, managing fuels at the urban interface, the maintenance of water points and access tracks, etc. Apart from being conventional wisdom to many, it is an historic and scientific fact that these measures, done at the right temporal and spatial scales, will make bushfire suppression easier and safer, thereby reducing bushfire losses.

Sadly, these days it seems it’s easier to ‘do nothing’ by way of landscape-scale mitigation – a prominent senior bureaucrat once said – “Better to fight wildfires and be a hero, rather than carry out prescribed burning and be a villain”.

And the ‘do nothing’ strategy can hide behind false, ignorant and ideologically-driven claims such as prescribed burning a) doesn’t work and b) it threatens biodiversity.

And it can hide behind the false narrative that it’s all due to climate change, and that zero emissions will see the end of bushfires. Oh when will they ever learn…

Well researched article Robert.

I was in Canberra a few months after the fires and took half a day up in the Brindabellas to look at the damage. I saw environmental destruction on a grand scale, not even man-ferns in the gullies were spared. Erosion gullies were over 2 metres deep everywhere and the river at Casuarina Sands was thick with mud.

Unfortunately, lessons aren’t learnt and the forest mismanagement continues. Tasmania is a disaster waiting to happen. It just requires the right meteorological conditions and here we go again.

Well researched Robert – had me reflecting on what some of the underlying drivers of the changes in management approach over the last 50 years and my sense is that it has happened in parallel with changes in perspectives on the environment amongst the broader community and, in particular, perspectives on disturbance of natural ecosystems.

The community seems comfortable with ‘acts of god’ conflagrations as outside of human control and, as a consequence these are ‘natural’, whereas other forms of disturbance say, associated with effectively maintaining fire trails in national parks with tree removal, and hazard reduction burning create feelings of uncomfortableness – now even amongst professional land managers such that they are not pursued to the point of being effective.

The environment is now imbued with a sense of otherness that make us, as a community, incapable of achieving outcomes that require disturbance.

Well done Robert.

Sadly things have got worse in the ACT. It used to be that fire management was based on training and experience at all levels.

Can you imagine an organisation that sacks their best best fire manager, Neil Cooper, who was representing Australia on behalf of the Forest Fire Management Group at an international conference, for buying a fellow attendee lunch with out permission from his superior? It took Neil 12 months to be reinstated with support from the Unions and others with character references.

There is an increasing trend across Australia with managers ignoring the principals set out in AIMS (Australian Incident Management System) and making decisions to do nothing because of the risk – not to the firefighters or the victims, but to themselves and their perceived reputation.

Best factual of the 2003 fire ever and no mention of “climate change” and “unprecedented”.

It will happen again and again as it has happened before and before that.