Because the forestry profession is far from simple and the work highly variable, I have tried to describe what a forester does by outlining the development of the profession in Australia. In Part 1, I outlined the broad principles of forestry and the development of the forestry profession up until WWII.

For this second part of the story, I thought I would focus on a couple of developments post-war which highlight the complexities of forest management and how it took several years of trial and error to develop workable practices.

The period immediately after the war was significant for a few reasons. Firstly, there was a rapid development of machine technology during the war which extended into the post war period. These changes had dramatic effects on society in general but also forest management and the timber industry.

Hopefully, I have helped answer the question – what does a forester do?

Post war technological advances

The post war era was one of great optimism for Australian forestry. Before the war, days working in the bush were long and backbreaking. Anything that promised to make the job faster and easier was quickly taken up. During the war, tracked machines and Army Blitz carriers were built and used.

Blitz trucks were produced in Canada by both Chevrolet and Ford using identical cabs with a characteristic reverse-slope windscreen. The Australian Defence Forces imported these trucks for the war effort. After the war, surplus trucks were available at very low prices, and many were purchased with the military bodywork removed and converted to a timber jinker.

The other major revolution in the bush from the 1950s onwards, was the heavy-duty power of hydraulic systems and associated handling equipment to lift and move large logs with apparent ease. Modified bulldozers and skidders replaced the tramways and bullock teams to winch, hook and bring the timber to a central landing.

The traditional tools of falling trees from settlement until after the war were axes and crosscut saws. The importance of the development of mechanised falling in the late 1940s was crucial. Timber demand, larger sawmills and rising costs required an increased output and more efficient operation in the bush.

Powered saws made their appearance in the 1940s. One was a portable straight bladed crosscut saw called a drag saw. Another was a mobile circular power or swing saw.

They were suitable for sleeper cutting. The first chainsaws that came on the market in 1945 required one operator to hold the motor end and another holding a handle at the end of the cutting bar to support and guide it. They were, however, heavy, expensive and unreliable. The two-man saws were replaced by lighter, better designed and more reliable one-man saws, imported from USA and Western Europe.

No longer was falling trees an impediment to the production of timber. The accessible forests could be selectively cut over again as chainsaws allowed the recovery of short logs from previously by-passed trees.

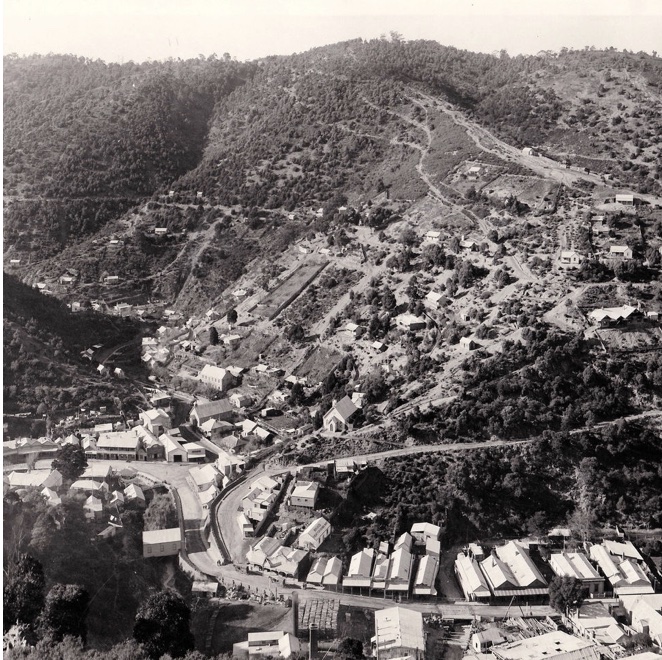

Sawmills were traditionally located in the bush close to the resource because of the limitations in moving large logs using horsepower. In some cases, tramways and railways were built to allow transport further distances using steam power. After the massive fires in 1939 in southern Australia, there was a push to shift the sawmills and the associated townships out of the forest. As the move towards electricity to power the mills became an option, the location of sawmills into established towns away from the bush became a reality. This also allowed bigger mills to be constructed with higher outputs concentrated in a relatively smaller area.

Sustained yield and mapping

The move to more efficient mechanisation in the forest improved the productivity of timber harvesting and nearly all areas of forest with easy access had been cut out or regenerating areas destroyed by wildfires.

Not long after each state had created forestry departments by the mid-1920s, they embarked on program of compiling working plans for each forest, to better understand what they were managing. Forest assessors carried out rudimentary assessments and mapping of timbered areas. They recorded types, quantities and sample measurements of trees at specific points, commented on soils, access routes and landscape features, and often undertook topographical surveys. But they struggled to achieve anything of consequence as they were hampered by deficiencies on finance, technology, information and science.

However, foresters did manage to establish inventory and yield plots to gain a greater understanding of the timber resource, adjust the cutting schedules on a sustained yield basis, and introduce silvicultural practices to ensure regeneration after logging. They tried to introduce this system based on the classical European theoretical teachings centred around the concept of a “normal” forest which supported a spread of age classes of equal productivity that would supply the timber industry with a stable and everlasting supply.

Unfortunately, the reality wasn’t that simple. Not only were a lot of the forests un-even aged and not structured to fit the European theoretical modelling, the forest departments were hamstrung as they only had very rudimentary, small-scale maps to work off that showed settled areas and private property and little else.

WWII made new demands for operational maps, at a time when many of the drafting personnel of the state’s Survey Offices became members of the armed forces, many to serve in the Royal Australian Survey Corps. The war revealed the gross inadequacy of Australia’s maps for defence purposes.

Even though the main battlefields for WWII were fought elsewhere, the war had a profound effect on forestry management in Australia. The Commonwealth Government essentially commandeered the supply of timber for the war effort, with little regard to sustained yield or silvicultural practices. The problem was made worse by the need to find supplies of appropriate substitute species for imports, which before the war, was one-third of total consumption. Immediately after the war, the problem was even further compounded as there was a significant post-war building boom, which saw the volume of sawn timber double in the decade between 1947 and 1957.

Foresters were very keen to manage the timber supplies to ensure the forests continued to supply the market into the future. To do that they needed more detailed maps of forest types and vegetation maps in the intervening years as a key planning tool for managing forest products after WWII.

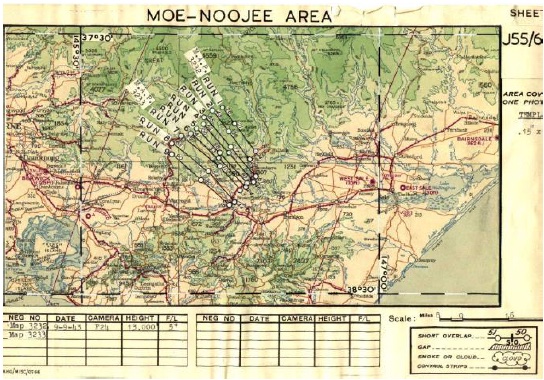

Forest Departments around the country utilised new war-time technology developed for aerial reconnaissance to map the areas under its control from black and white photography. Aerial photography was first trialled in WWI using light-aircraft reconnaissance and was first used for forest surveys in Australia in the 1930s.

A section of northwest Tasmania and the tropical “jungles” west of Tully were photographed by the Federal Air Board. The latter work was done to examine large tracts of land and determine their value for exploitation. The Federal Air Board was initially set up to establish the Royal Australian Air Force in 1921, which it administered.

During WWII, large areas of Victoria were photographed by RAAF to develop a way to plan and record things such as direct hits after bombing raids. Immediately after the war, the Tasmanian Forestry Commission was one of the first to form a small, specialised photo-interpretation section, staffed by ex-members of RAAF and WAAF who were specialists in this type of work.

This new aerial photography work was supplemented by ground surveys along strip lines that began an era of rapid progress in mapping and assessment of forest resources and helped make foresters and the forestry departments leaders in this field.

With more extensive use of aerial photography, the need for detailed on-ground timber assessment decreased, but data was still collected in the field where required. The efforts of the earlier tree markers and foresters before the war must not be underestimated in this context as they provided ground checks on the photo interpretations through extensive field surveys.

The outcome of this photo-interpretation work was maps at various larger scales to enable foresters to describe and map the structural features of the vegetation, such as height, class and crown cover. They called these forest type maps, and they were the basis for scheduling future operations, and setting up long-term inventory plots to determine the sustainable rate of cutting. By the end of the 1960s, the entire state forest regions were mapped and typed, a massive undertaking and achievement.

I can vouch for how valuable the forest type maps were for detailed planning and field work. I often used to carry out desk top planning on forest type maps without contours and other features to remove clutter. This allowed me to assess potential resource areas before going into the field. I knew by the forest typing where the ridges and gullies were and only looked at the contours later when trying to mark in preliminary road lines and harvest boundaries on the map.

In Western Australia, aerial photography played a major role in mapping the spread of the dieback disease fungus Phytophthora cinnamomi. This type of accurate broad-scale mapping of vegetation deaths was unique at the time. It was valuable in assisting managers to locate quarantine areas and to isolate and monitor diseased pockets of the forest.

The key to a sustainable yield was to ensure that harvested forests regenerated quickly and effectively. Silvicultural systems were developed for most forest types depending on the condition and structure of the forest and the markets they were serving. However, in the wetter forest types, there were always problems achieving sufficient regeneration after logging.

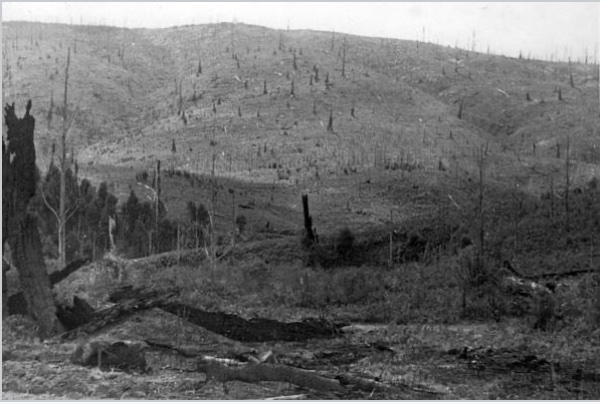

Critical research work in Tasmania and Victoria in the late 1950s, showed that clear-felling an area of forest, burning the debris and re-sowing with seed, initially from trees left on the coupe, then later from seed collected prior to or during harvesting, created ideal conditions for regeneration.

Just like natural wildfire, this harvesting strategy left behind a clear seedbed so that seedlings could grow quickly. But clear-felling meant that a large quantity of lower-grade wood was harvested, along with the high-quality sawlogs. A new market was needed for this additional low-grade material. Logs only suitable for woodchipping to make paper pulp and composite timber products, such as particle board, had always been produced from sawlog operations using selective harvesting techniques to feed the existing processing plants in those states.

However, in order improve the degraded forests that had a been high graded by sawmillers and sleeper cutters for over 150 years and ravaged by severe wildfires, an additional market was required to fully implement the new clearfall, burn and sow silvicultural technique. That is why the export woodchip market was pursued and established in the early 1970s.

One thing in favour for the foresters was that the increased mechanical disturbance in the forests meant there was no problem with regeneration in some areas. But fires were a problem that needed to be addressed.

Development of the world’s best fire management system

Gaining an understanding of fires and how to manage them was based on operational experience and incremental changes of several years. Aborigines had regularly burnt the landscape for millennia and bushmen, settlers and pastoralists followed their lead.

The first foresters from Europe believed Australia’s forests were best served by keeping fires out, including deliberate burns. They focussed on building firebreaks and detecting fires early and getting order in the forest, but they treated fire as an enemy that had to be excluded. The focus was on suppressing any fires that occurred as quickly as possible.

The idea that lighting a fire in mild conditions and reducing the fuel levels was seen as an anathema to getting regeneration. The early foresters believed that if used frequently, fire would also damage the soil. The reluctance of foresters to burn coincided with less and less fires as a management tool in the general rural landscape, as paddocks were fenced and grasslands were kept down by grazing.

Unfortunately, this meant over a relatively short period that large areas of forests carried high fuel loads. The new forest departments were confronted with very large fires in 1926, 1932, 1934 and 1939.

After the war, fire management didn’t change much. Younger foresters who were trained in Australia began to question the status quo about fire management. At the Royal Commission into the 1939 Victorian fires, Judge Leonard Stretton laid bare the failed fire policies of the foresters and he insisted changes were required. Gradually more resources were provided, and some proactive burning was carried out.

But it was still insufficient to manage the fuel levels over a vast estate. Consequently, there were further damaging fires in Victoria in 1944, New South Wales in 1952, Western Australia in 1960/61 and Victoria again in 1962 and 1965.

Meanwhile, in the ACT, Alan McArthur, a forester from the Commonwealth Forestry and Timber Bureau was the first person to conduct research on fire behaviour. He carried out many, many experimental burns in the foothills of Black Mountain in Canberra and in the neighbouring Brindabella Ranges. He also did some research in the jarrah forests in Western Australia. He gathered a huge amount of empirical data over many hundreds of burns and developed a few fundamental relationships in fire behaviour. From his work, he strongly advocated for fuel reduction burning to reduce the impacts of wildfires and to make it easier to control those fires.

Each state created its own dedicated fire management branch. In Western Australia, George Peet, who as a young forester fought the Dwellingup fires of 1961, had a passion to prevent further damaging fires. He continued the work of McArthur in the state carrying out hundreds of experimental burns which he analysed and recorded. Through his work, he produced a controlled burning guide.

Similarly, in Tasmania a Fire Protection Branch was created in 1940. They built several fire towers to detect fires and improved the equipment to fight fires and were instrumental in the formation of an adequate bushfire brigade organisation. Some fuel reduction works were done opportunistically by field staff in the 1950s and 60s. However, the priority at the time was on silvicultural burns in the wet forests to ensure regeneration. Hot logging slash burns were required, and little was known about the best method for do them. The challenge faced by foresters was the burns had to be hot enough to get a satisfactory ash bed without escaping.

It took a long time before the art of high intensity regeneration burns was well established. Systematic work on how to achieve safe, hot burns began in 1965 by Ken Felton and Eric Lockett, foresters based in Maydena in the tall, wet southern forests. Numerous trials and operational experience from several people finally gave rise to guiding principles which led to a manual and specialised training for foresters.

I am still amazed at the level of detail and training I received for high intensity burning that gave me the confidence to carry out a controlled, hot slash burn. It is a nervous experience but totally rewarding when done properly by applying the broad scientific principles. Protagonists on the sidelines who criticise foresters for carrying out these burns demonise them as rednecks who don’t know what they are doing. They know little of the pre-burn planning that is required using fuel hazard sticks, an intimate appreciation of local weather patterns and a detailed knowledge of fire behaviour principles and science to carry it off successfully.

Most foresters will recall the opportunities they had to learn from experienced peers and field workers who lived and breathed fires and passed on valuable practical experience that was paramount in applying the theoretical knowledge learnt in the classroom. I was very privileged and grateful to work alongside quite a few and benefited from their knowledge and experience.

It gave me the confidence I needed when I had to make critical decisions fighting some major wildfires, sometimes literally shitting myself, and carrying out planned high intensity burns, that I doubt I would have had the fortitude to do without that training and previous experience.

It was the devastating Hobart fires in 1967 that shifted the focus on fuel reduction burns in Tasmania. Small fires were lit by drip torch on the ground, but they needed to be carried out on a much larger scale to be effective. This was the same issue faced in the other states.

The idea of lighting fires over a much bigger area from aircraft was born from a collaboration between George Peet and David Packham from the CSIRO. Packham was a chemist, and a trained pilot who worked closely with the Bushfire Section looking at heat transfer. Both men came up with the idea of flying over a forest under suitable weather conditions dropping incendiaries. A lot of work had to start from scratch to find appropriate incendiaries that were non-explosive, cheap, safe to transport and with a timing device to avoid igniting in the plane.

Further work led to the introduction of a small plastic phial filled with Condy’s crystals injected with liquid ethylene glycol. The ensuing chemical injection would result in a brief hot fire and ignite the dry fine fuel on the ground. A machine had to be developed to safely inject the phials with the glycol and eject them at the right interval.

After months of work setting up an aerial fire-bombing system, the first trial occurred in Western Australia in December 1965 at Pingerup in the Shannon Division.

The other states soon followed Western Australia by adopting aerial burning on a landscape scale. It revolutionised the ability of foresters to burn out at least five per cent of the estate in low intensity burns spread over targeted areas and helped firefighters keep on top of fuel levels reduce the large wildfires over hundreds of thousands of hectares during severe bushfire weather.

The Victorians led the way in developing aerial fire-bombing techniques to control wildfires. They first started trials in in 1937-38 but the 1939 fires and the war stopped that work in its tracks. In 1946, they resumed trials at Anglesea comparing the performance of RAAF P51 Mustangs, B-24 Liberators and Avro Lincoln Bombers dropping 500-pound bombs of ammonium sulphate compounds. The work was inconclusive, but testing resumed in the early 1960s trialing bentonite clay and Phoschek. The first operational drop of fire retardant at a fire occurred in 1967 and the application of firebombing was born.

Foresters were quick to adopt the bombing, spotting and aerial photography techniques that were all evolved from military activities from the two world wars and they quickly became leaders in the world in these practices.

Australia’s fire management system had become so sophisticated by the 1980s that the most industrialised country in the world looked on in envy at our success. The USA continued to suppress fires when they started and did not develop their own fuel management program. Whenever they got any big fires they used large air tankers to try and aerially bomb the fires with water and fire retardants without much success. They had a very limited on-ground fire fighting force.

The irony is that not long after Australia had put in place its dedicated world-leading fire management system, it was forced to scale it back through public pressure and a gradual dismantling of professional forest management that has occurred over the last 30 years. In contrast, North America has started implementing widespread thinning and active fuel management to deal with their growing wildfire problem. No longer does the USA enviously look to us when it comes to fire management – simply because we have moved away from a proactive system of preparing for fire seasons, to an emergency response once fires start. With that change since the 1990s, we have seen a dramatic increase in the areas of forest badly burnt, the number of houses destroyed and the number of lives lost.

The Age of Aquarius

Up until the early 1970s, foresters were required to manage forests primarily for wood products. The emphasis on wood production was simple – Australia supported important forest industries, particularly sawmilling, mining timber operations and the production of paper products that helped build the country during its momentous expansion in the post-war years of the 1950s. Virtually everything was made from timber, not plastics, not aluminium, and not cement.

However, foresters were confronted by increasingly complex land use issues that reflected a rapidly growing and affluent society. Greater consideration was given to uses of the forest other than wood production and society demanded a satisfactory settlement of the issues. Foresters were required to implement a much broader and more flexible approach to their practices than in the past, with greater consideration given to other uses.

While incidental benefits accrued from forest management such roads, protection of forests from damaging wildfires, insects and disease, they were not seen as important.

What was more important, was a greater public emphasis on recreation, aesthetic and wildlife values. However, in New South Wales, foresters were the first to show a concern for the environment in the 1930s by advocating an amendment to the legislation to create National Forests which, as well as producing timber, were set aside for other uses such as catchment management, recreation and the protection of wildlife. It was the first expression of multiple use management in the country.

Without fully understanding what role a forester played in meeting the new social requirements, the public and the media questioned their role. Foresters were portrayed as being unyielding and unwilling to change. Yet across all the states in the 1970s, they brought in a concept of multiple use management that gave equal weighting to non-forest considerations as part of providing a sustainable timber resource for the public.

Part of the problem for foresters was they were given little credit for the knowledge they held and gained through their professional work. There was no recognition they had the ability to adapt their management to meet changing demands of society relatively easily. Once foresters started dealing with extreme conservationists or spoke to non-foresters, they quickly realised that much of their knowledge was taken for granted and their expertise was a complete revelation to the uninitiated.

Even today, people have no idea that the basis for most forest ecology work carried out today in reserves comes from research carried out in productive forests by the forestry departments and foresters in the past.

Foresters are involved in the stewardship of the forests. They seek to deal with the complexities of sustainable forestry so that our environmental, social and economic needs are met in a way that reflects true social justice and equity for all. This includes understanding the degree to which our regional communities, often supporting the less well-off segments of society, benefit from the employment generated from the forests. In terms of stewardship, foresters seek to maintain respect for a wide range of competing values which different people hold and focus on an appropriate compromise and balance in managing the forests.

An example of stewardship which is never recognised, is the ability of foresters to assess stand dynamics. The ability to observe, describe and interpret the dynamic status of a forest is a fundamental basis for silvicultural practice. Experienced foresters develop an innate ability to understand the consequences of competition between the components of the forest and their relationships to each other through time. I touched on this in Part 1 when I described the forester’s role as that of an “environmental detective” searching for clues on the history of the forest and assessing its condition and thus determining the appropriate silvicultural strategies required. Through this skill, foresters can describe the history of any forest stand in the country.

For human societies to survive in the current climate with our standard of living, requires us to grow food, produce materials and fibre for clothing and shelter, and to clear areas to live on. This requires compromise everyday between preservation and exploitation. It is not a question of whether or not, but a simple question of how. There are few absolutes, it is always a question of balance.

Forest management is one of the most benign forms of land management. On a sustainable basis, that is when harvest is in line with growth, and when soils and biodiversity are maintained, it is far more benign than other land uses such as agriculture, mining and urban developments.

The resilient nature of forest management under the excellent stewardship of foresters is best exemplified in the following story.

Some salvage and twice burnt areas of state forest on the south coast of New South Wales were added to the Nadgee Nature Reserve on 1 January 1997. It then became part of the 18,880 hectare, Nadgee Wilderness. A section of the similar area over the border in Victoria was subject to extensive seed tree logging in the late 1970s, as well as experiencing some intense wildfire events. It was included in the 25,000-hectare Howe Wilderness Area in 1992. The reason both areas were given wilderness status was because they purported “to be the best representation of pre-European coastal vegetation in south eastern Australia”. The previous management by foresters that gave rise to these wonderful forests was never acknowledged then, nor is it now.

There is a similar tale of the beautiful forests on Fraser Island. The island and its vegetation are considered so special, they were given World Heritage status after 120 years of forestry management. Nearly 40 years after active forest management ceased, tourists marvel at the magnificent forests near Central Station but have no idea that they are a product of the clearfelling of the tall open blackbutt forests by foresters.

The claim that forests are destroyed by logging does not hold true. Forestry does not equate to forest clearing. An area harvesting for trees is regenerated back to native forest (see photos above). Much scientific work has gone into ensuring that our regeneration practices reproduce the functioning natural ecosystems, and our harvest levels are sustainable.

In fact, our forests are extremely resilient. An example is during the gold rush days around Walhalla in Victoria where the surrounding hills were totally denuded of timber cut for the mine boilers. Today, those same hills are covered with trees. The greenies now claim the forests are virgin that have survived since European settlement.

One of the great virtues of forestry is humility. We are taught to always be open to new and better ideas and ways of doing our business. Forest sustainability is not a destination, but a journey. We often do not achieve the outcomes we aspire to, but we are always willing to learn and that improves our practices.

Forestry involves cutting down and regrowing trees. It is one of the very few renewable options we have available to us – it is truly the ultimate renewable, and yet, here we are in 2023, with the media, activists and certain scientists calling a climate emergency every other day, willing to turn a blind eye to the unequivocal science of sustainable forestry.

Foresters know that we can manage forests for multiple uses. We can have conservation, clean water, carbon sequestration and timber production. Timber is a renewable resource.

With so much productive forest now locked up in national parks, we have to rely on substituting timber products with those made from plastics, aluminium and concrete. For example, railway sleepers and poles are now made from concrete; windows and house framing are increasingly made from aluminium and steel, the majority of clothes pegs are all made from plastic; the list goes on. Those substitute products are not renewable and come from large iron ore mines, sand mines, limestone quarries and oil drilling operations.

I hope after reading my series on “What does a forester do?” you get an appreciation of our passion for the environment and the requirement for a pragmatic approach to balance competing interests associated with utilising and saving our forests, and through that, an understanding of what we do.

Another great story. It is a shame Andrews and Silly Lily wouldn’t bother reading how sustainable forestry is.

Thank you Robert! An affirmation of a 45 year forest career for me and a reflection on other suite of skills required to be endowed on our successors – if they listen!

An interesting take on our profession from your perspective. There is nothing in here to disagree with and some personal lived experience. There are so many specialist disciplines within our profession. These meant that foresters were among the brightest students that our schools produced. In the 1970s entrance to a forestry course at Melbourne Uni required HSC mark 2nd only to Medicine. The specialist areas in forestry such as resource modelling, entomology, pathology, genetics, physiology, ecology attracted the brightest minds. These specialists were often employed in State forest agencies, so had a pragmatic approach to science. Unfortunately much excellent work only ever made it into “internal” reports and technical bulletins rather than peer-reviewed science journals. The Commonwealth and States supported several Research Working Groups which facilitated regular meetings and collaboration from the 1950s until the late 90s. This program also declined with the decline of State agencies, abolishing CSIRO Forestry Division and gutting the forestry section in DAFF. The leadership of forestry in government and the private sector has few, if any, foresters. Such is the decline over the past 20 years. It’s a tragedy that Australia cannot afford.

Just as a comment on the “internal reports” aspect – I have spent a bit of time pouring over old technical reports from Victorian forest managers from the 1980s/90s and the irony is, while these are considered “grey” literature now, the quality of the work done would mean it could easily be published in peer reviewed journals, and would often be better than some articles I read today.

I do often think this is a function of the changing nature of scientific journals now – there are a huge range of publications now, and more opportunities to get into the literature. It’s extremely unfortunate that the technical reports are disappearing down the memory hole.

Good article Robert.

But I think in your section Age of Aquarius you might consider the role of foresters in management of national parks in Queensland – formally established under the State Forest and National Parks Act 1906 with the first National Park (Witches Falls Mt Tamborine) formally established in 1908.

National Parks were managed by the forestry authority (initially Forestry Branch Lands Dept morphing into Qld Forest Service, and eventually Department of Forestry) with further legislative cover under the Forestry Act 1958.

From day one, until the establishment of the National Parks and Wildlife Service in 1975, foresters were responsible for acquisition and management of National Parks. After 1975, many foresters transferred to the QNPWS in senior management roles.

To quote Bill Wilkes, one-time Secretary of QFD, in his Romeo Lahey memorial address to the Qld NPA: “At this stage I should like to comment on the administration of National Parks by the Department of Forestry in this State. It is a question which often arises. I would like to say that, in my opinion, foresters by the very nature of their training are in the forefront of the most competent conservationists available to administer such areas and generally speaking, are most dedicated persons in the cause of nature preservation.”

Queensland was unique in Australia in charging foresters from the outset with the management of National Parks.

Great points Ian.

Yes, I should have referred to Queensland’s unique legacy in terms of foresters and early national parks.

I think this topic deserves its own story, and I will give thought to writing that story in the future. I should get more of a appreciation of the Queensland story as I delve deeper into my research for the Fraser Island book.

With regards to your statement: “In fact, our forests are extremely resilient. An example is during the gold rush days around Walhalla in Victoria where the surrounding hills were totally denuded of timber cut for the mine boilers. Today, those same hills are covered with trees. The greenies now claim the forests are virgin that have survived since European settlement”.

We have the same with mulga, which was first used for drought fodder about 1875 and continuously since. With somewhat shock effect I have described some of the claimed areas as “about as pristine as a recycled virginity”.