“There was not much money anywhere and if you saw a rabbit, that was money. If you could get him, it was a bit of silver in your pocket”. Max Weber

The rabbit comes to Australia

Queensland, like other states, has suffered damage from several introduced pests, particularly prickly pear and the cane toad. However, the most expensive nuisance to the pastoral industry has undoubtedly been the rabbit.

The earliest record of rabbits in the country was a report in May 1788 from Governor Phillip to Lord Sydney in London, where he wrote he had five rabbits. Then in June 1826, an enterprising settler imported large numbers of rabbits to his reserve on Betsy Island, Tasmania. He leased the island for breeding rabbits for their fur, expecting to get at least ten shillings from Chinese buyers. However, his venture failed; the following year, the common rabbit became numerous throughout the state.

In the same year, there were records of numerous rabbits introduced by whalers on Rabbit Island, off Wilson’s Promontory.

Thomas Austin of Barwon Park near Geelong liked hosting friends for a “good old English hunt”. So he bred game on his property, including rabbits. By 1864, Austin was proud of his success as the number of rabbits increased and spread on his property. Beaters made the rabbits bolt into the open out of the long grass. The gentlemanly sportsmen shot thousands of rabbits, but more survived and continued to multiply. Austin even hosted Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1867. Two years later, the rabbits had spread far from his property, 35 miles to the east and 12 miles to the north-west. Initially, landholders didn’t mind as they enjoyed shooting them. However, by the early 1870s, rabbits had spread into South Australia and made their mark across the landscape creating vast deserts in their wake.

Rabbits quickly became a pest mainly due to their extraordinary reproductive ability. They begin breeding at three to four months old, with an average gestation of 30 days. Females usually produce an average of six in a litter and can have five or more litters a year.

The rabbit had a few native enemies, such as the dingo, goanna, snakes and birds of prey. But they did nothing to stem their numbers. People turned to domestic cats and let them loose in the bush, but rabbits killed the cats. Post-mortems showed the cat’s stomachs full of balls of rabbit fur. Authorities considered introducing weasels, ferrets and the mongoose. Another proposal was a red meat-eating ant from Natal, but outback residents thankfully considered they were already over-supplied with ants.

Rabbits, rabbits everywhere – entry to Queensland

After hearing about the success of Austin’s shooting parties, the Queensland Acclimatisation Society decided to introduce the rabbit in 1864. The Honorary Secretary offered two shillings per head for the first half dozen bred in the colony. However, farmers expressed concern about proposals to turn some loose as they might become a nuisance.

Meanwhile, rabbits had spread into Victoria’s Wimmera and Mallee districts, where pastoralists had to abandon their runs. Rabbits moved across the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers in 1878 and through south-western New South Wales northwards along the western plains between the Darling and Lachlan Rivers to Wilcannia.

By 1879, landholders grew alarmed at reports out of Victoria and New South Wales, where rabbits had taken over thousands of square miles of land which formerly carried sheep. The local member for Dalby told Parliament that the rabbit nuisance was a significant threat to the grazing and agricultural area of the Darling Downs. Parliament introduced A Rabbit Nuisance Bill in 1879 and a Bill to Prevent the Introduction of Rabbits into the Colony of Queensland the following year. However, considerable debate ensured where opinions differed across the rural city divide. Members from the pastoral districts wanted rabbits kept out and the extermination of any already in the state. The city-based members could not see why children could not keep rabbits as pets. Parliament eventually passed the Bills making it illegal to import rabbits into Queensland and an offence to turn rabbits loose.

But the legislation did nothing to stop the continued advance of wild rabbits further south, even though the Minister for Lands in Queensland was satisfied that New South Wales had checked the rabbit’s spread, aided by a severe drought at the time.

Humphrey Davy was appointed in July 1885 to visit the country in New South Wales adjacent to the border and reported that fencing was the most successful and cheapest method to keep the rabbits outside the state. A public meeting in Charleville also called for a rabbit-proof fence south of the Western Railway that was being constructed from Roma to Charleville. A change in government passed the Rabbit Act 1885, which advocated for a border fence. Unfortunately, the tender for the construction of a rabbit-proof border fence was not approved until 1886, by which time rabbits were scattered from Wompah in the west to Mungindi in the east.

As there were no rabbits on the Warrego River, the government decided it was unnecessary to build the fence eastward of the Warrego. The fence started in 1886, about 16 miles west of the Warrego River. It was a gigantic undertaking. By 1891, the fence had been built westwards about 266 miles to within a few kilometres of Haddon Corner in the far north-east of South Australia and was later extended east to Mungindi and completed in 1903.

Between 1892 and 1905, Queensland was subdivided into nine Rabbit Board Districts. The Boards for each district were empowered to raise funds from local stock owners, and they were required to contribute to netted barrier fences to keep the rabbit out by erecting the skeleton posts, to which the government would add the netting. As a result, barrier and check fences were hastily erected, and rabbits had already invaded some districts before the fences were complete.

By the 1920s through to the 1940s, all this work didn’t stop a rabbit plague crippling farms across Australia, and Queensland was one of the hardest-hit states. When droughts affected farmers, any bit of rain was welcome. But all it did was provide fodder for the rabbits, who ate tiny green shoots that sprang up overnight.

Saving a community

For all of the problems a plague of rabbits caused rural Australia, the small border town of Texas on the banks of the Dumaresq River, saw an opportunity. They developed a vibrant, sustainable local economy based on trapping, processing and selling rabbit meat and skins. Turning rabbits into a valuable local industry saved the town during the Great Depression. Local trappers became wealthy, women could contribute to the household finances, and children outearned their teachers.

Rabbits first arrived in the Texas area between 1900 and 1902. They quickly ate all the best grass, making life difficult for the sheep. They gradually increased in numbers to plague proportions. During the Great Depression, Texas had no work for its residents, and government handouts were small. Rabbits made it impossible to work the land. So men began trapping the rabbits to feed their families. They soon found that they could sell them profitably.

In 1928, the Amalgamated Rabbit and Skin Export Company Limited began building a freezing works factory in Texas to process rabbits. The business started taking rabbits in 1930, and in their first two weeks, they processed 30,000. Their market was London, and they sent three tonnes of rabbit carcasses, with their fur and heads intact, daily to Tenterfield and then onto Sydney by rail in cold storage to be picked up by the first Orient boat to England.

When the railway line was completed to Texas, four tonnes were sent to Brisbane daily and loaded onto ships which sailed directly to England.

The English were keen to buy Australian skins over their local product because the Australian trapper dried the skins on wires, whereas the English rabbiters just threw them in a heap to crumple, making them hard to process. The market was huge. It originally started from Adelaide in 1897, and throughout the 1920s, carcasses sent from across Australia averaged nine million per year, worth £400,000.

About 8-9 trucks had daily runs along all roads that led to Texas to collect rabbits that trappers caught overnight. Each trapper had a screen box made of hessian beside the road, and the rabbits, in pairs, were placed in these boxes with their innards removed. The rabbits were unloaded into the chilling room when the trucks arrived at the factory.

They then went to a packing room where they were graded into small and large sizes and checked to ensure no bruising or damage to the carcass. Any damaged rabbits were skinned and boned, and the meat was consumed in Australia.

The export rabbits were packed in wooden crates approximately 3 feet by 18 inches by 6 inches, and each crate contained 14 pairs. The crates were placed in one of three cold rooms where they were frozen. Each crate was stacked so that the cold air could circulate.

A special train came to Texas once or twice a week with 6-7 wagons. The wagons were insulated, but the ice was packed at the end of each wagon. Ice was made in the factory and supplied to the community for their ice chests.

They may not have dressed or looked wealthy, but during the Great Depression in the 1930s, the trappers were among the highest income earners in the country. The rabbit industry would have been worth $10 billion in today’s dollars – more than beef exports today.

During the WWII, the industry sent most rabbit skins to America and the country was paid in credit. They exported about 50 million rabbits each year during the war, earning the country two million pounds towards purchasing war material and weaponry.

The beginning of the end

After the demand for rabbits in England declined in the early 1950s, carcasses were sent to the United States for a trial period. Rabbits were skinned and put in plastic bags, but the venture was unsuccessful.

After the exports ceased, rabbits were skinned, and the carcasses were sold to all parts of Australia for human consumption. Next, the company added a drying room to the factory, and the dried skins were sent to Akubra to make their iconic hats and the Sydney fur market. Finally, the rabbit heads were sent over the border by truck to be buried in the sandy ground using a pick and shovel. In later years, Council built a much larger trenched hole for the burial of the heads.

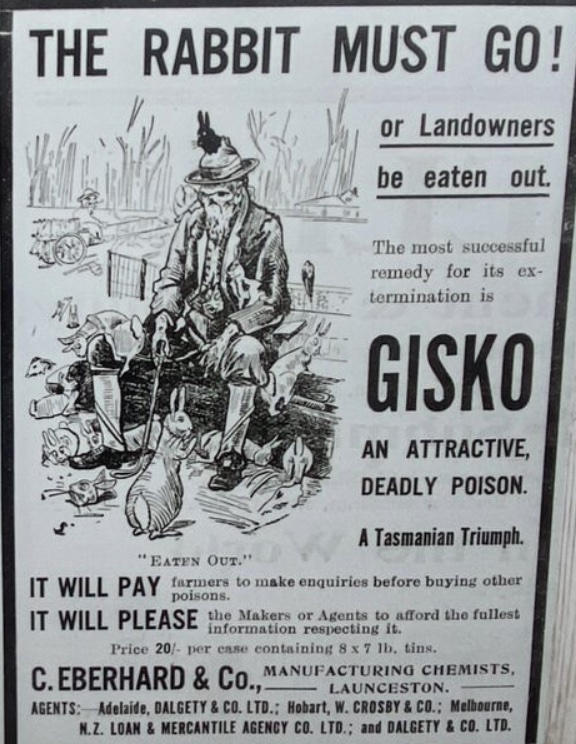

The rabbit plague peaked in the 1940s. Poisons, like Gisko, came into fashion to kill the rabbits. Poisoners would lay long trails of poison each night. While the number of rabbits for the factory grew from the poison drops, the poisoned carcasses weren’t good for eating. Moreover, the flesh was red compared to the pale pink of trapped rabbits, so the skins were the only saleable portion.

But it wasn’t until the introduction of the Myxomatosis virus that rabbit numbers were affected. The virus killed 99.8 per cent of infected rabbits in 1952. As a result, it affected the Texas rabbit industry for a brief period. However, in a surprisingly short time, wild rabbits developed resistance to the virus, and their numbers grew again from 1958 onwards.

The Texas freezing works factory continued until 1992, when the factory finally closed.

Visit the museum

Rabbits have been Australian agriculture’s most costly vertebrate pest animal and, along with the fox and cat, one the biggest menace to threatened native species.

Queensland has been the only state that made it illegal to keep rabbits for over a century. But in a great irony, the value of the rabbit industry was so significant to the border town of Texas that for over 30 years, from 1929 to 1960, the value of rabbits to Australia’s economy was more lucrative than coal.

Today, the fence still exists and is maintained by The Darling Downs-Moreton Rabbit Board. It is the oldest and longest purpose-built rabbit-proof barrier fence in Australia and possibly the world. The Rabbit Board is the only organisation still specially dedicated to eradicating rabbits in the country, protecting 28,000 square kilometres of south-east Queensland with a 555-kilometre fence.

If you ever visit Texas, stop and visit the Rabbit Works Museum which has detailed information about the rabbit industry. I am sure you will enjoy the experience.

Some good history here. Margaret Kowald has just written the history of the Darling Downs and Moreton Rabbit Board. I think the book is available in the Texas Museum.