After James ‘Philosopher’ Smith discovered the rich Mount Bischoff tin deposit near Waratah in 1871, there was a keenness to prospect other areas of the West Coast region. Prospector William Robert Bell was one of them. He was employed by the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.) in May 1875 to carry out prospecting on the eastern boundary of Hampshire Hills following the discovery of tin near Mount Housetop, some three miles away. His made a promising find of some tin deposits at Marsdens Creek, near the Emu River. Bell immediately sunk a shaft and was instructed by geologist George Ulrich to explore the lode above the Emu River flood mark. Bell thought he had made a similar find to Mount Ramsay and sent samples to Ulrich in Melbourne. There was initial excitement over the find, with James Norton Smith writing:

“There seems to be no doubt that Mr Bell has found silver in the adits he is driving at the Hampshire Hills and there is every prospect of a rich mine”.

After many phases of mining, the optimism proved fruitless, and the Hampshire mine was not profitable at all.

But another silver discovery is probably Bell’s most significant in Tasmania as a prospector. Following Smith’s footsteps, Bell went to Bischoff and traced the tin lodes at the North Bischoff Valley. He later found some silver-lead mineralisation adjoining the North Bischoff Valley Tin Mining Company lease in December 1879. The Mount Bischoff and Donaldson Track Formation Association was formed to provide funds to Bell to blaze a trail west from Waratah over the Magnet Range towards Heazlewood and then southwest along the Whyte River to Corinna.

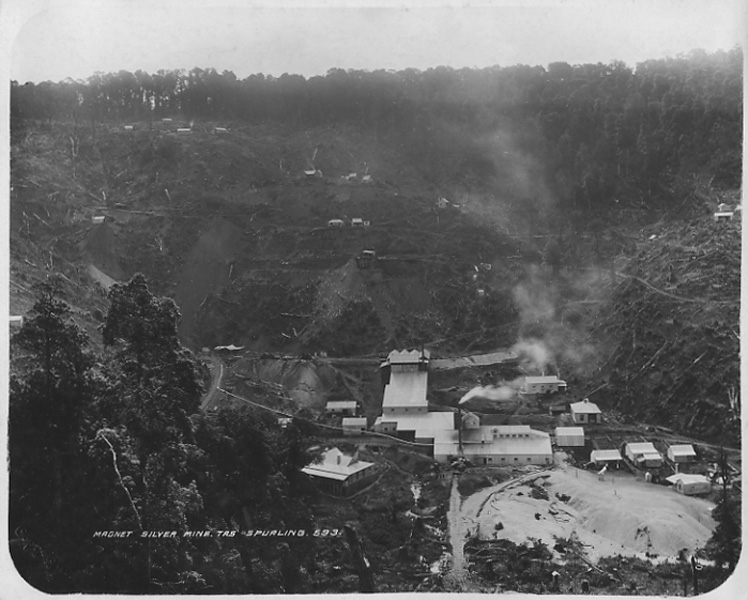

Bell explored parts of the Arthur and Pieman River systems and first discovered Tasmania’s mineral emblem, crocoite, at the Heazlewood mine in 1887. In 1890, he found a rich silver lode in the Magnet Creek valley about five miles west of Waratah, and camped at the spot where the Magnet mine was later developed.

Bell immediately pegged two claims, and it wasn’t until three years later that a concerted effort was made to exploit his find. Bell had driven a 30-metre adit to intersect with the lode, producing about 30 tonnes of ore. A rough pack track was blazed to the site to transport the ore to Waratah.

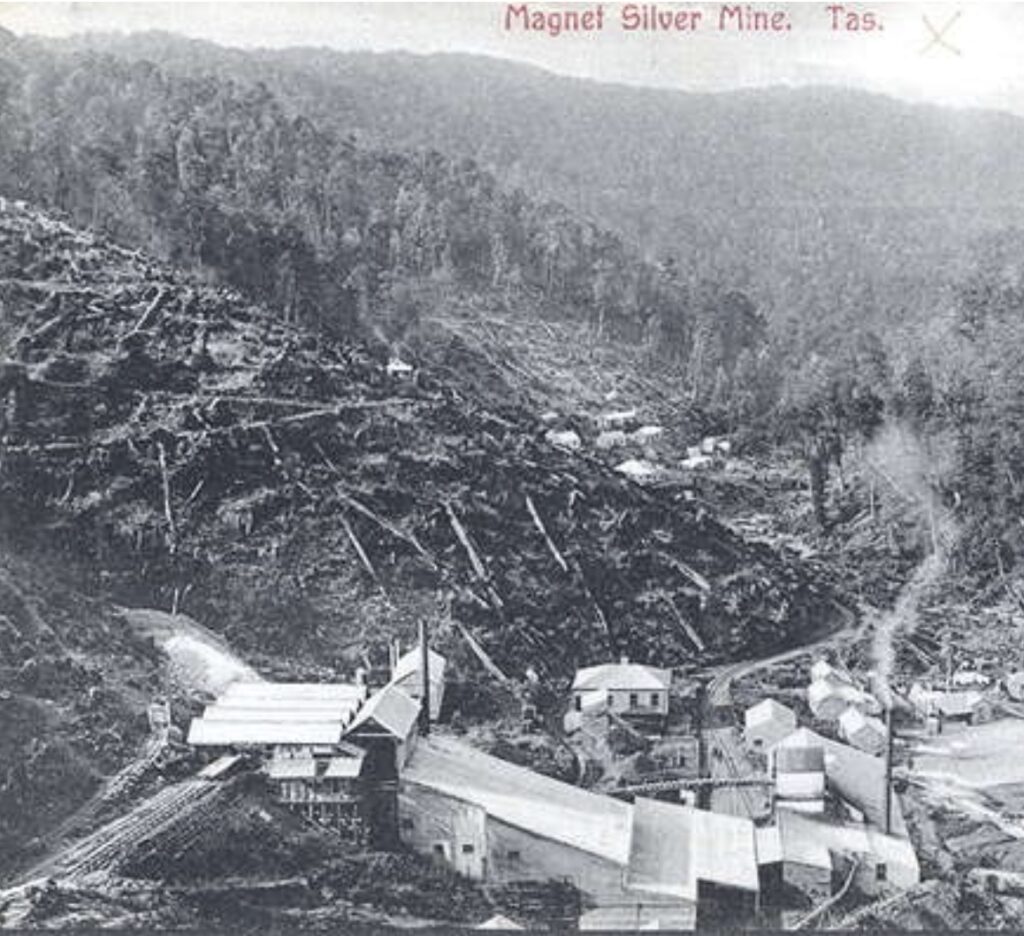

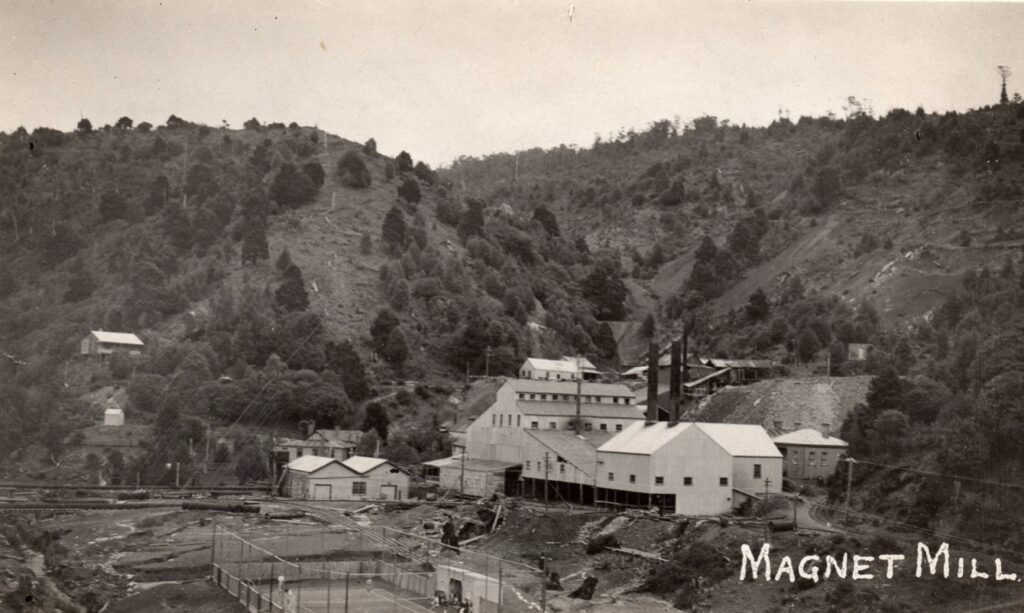

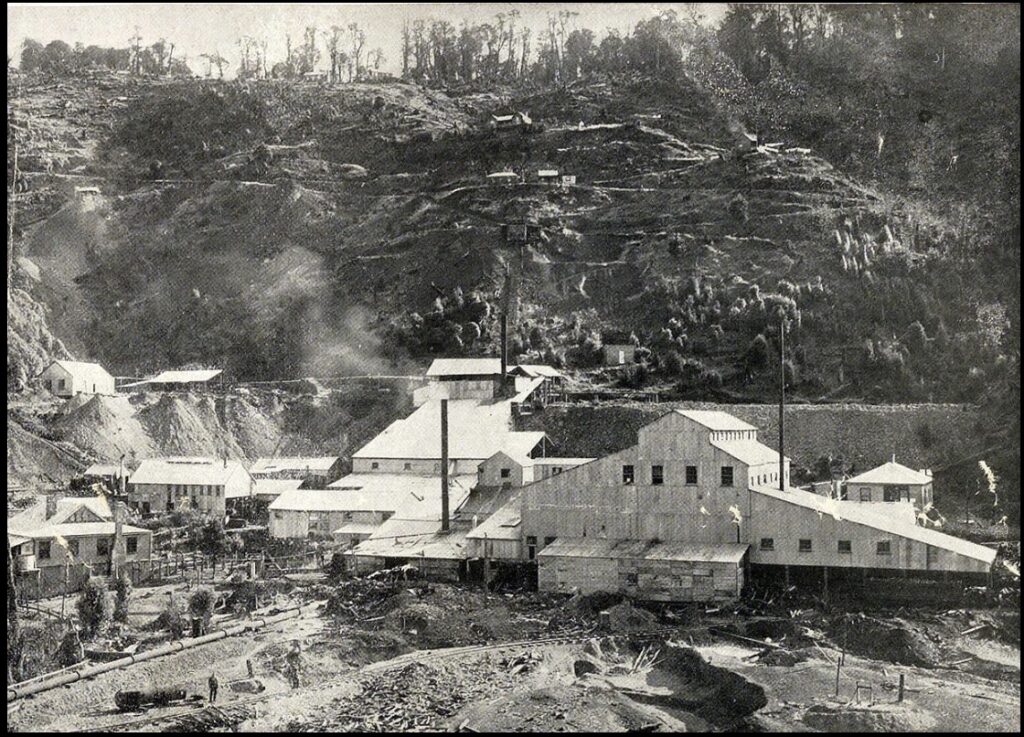

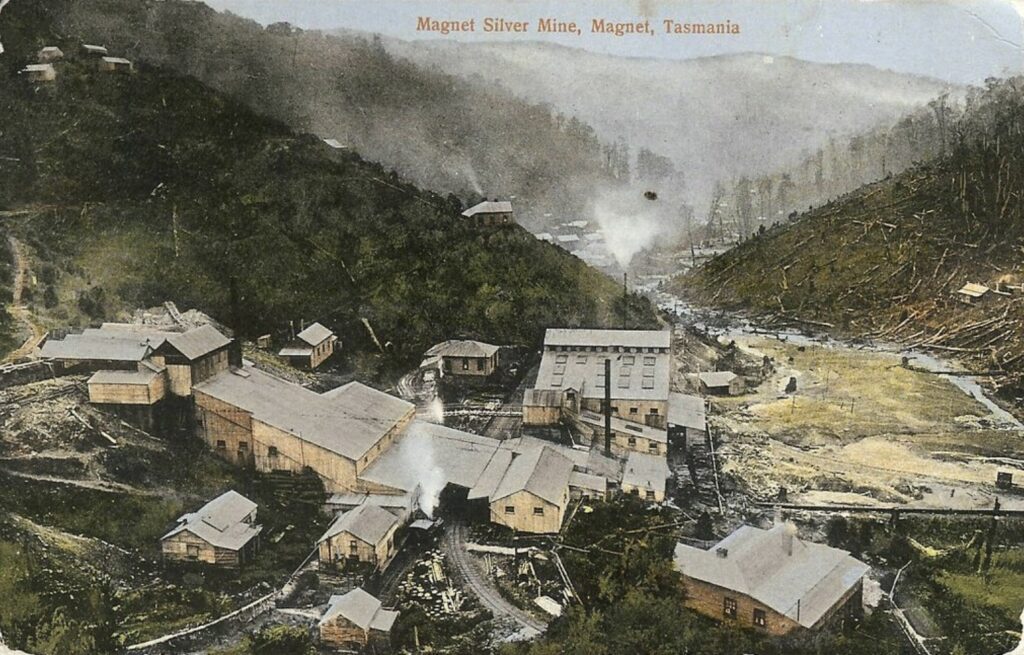

The Launceston-based Magnet Silver Mining Company was formed to open a mine which, although close to the already established mines at Mount Bischoff, was separated by a deep gorge in the headwaters of the Arthur River and at a significant elevation difference.

Trial ore shipments were sent to Hamburg in Germany and Maryborough in Queensland for processing. At a meeting in 1897, the shareholders agreed to raise funds to pay for the further development of the mine. They employed Thomas Jones as mine manager and called tenders to drive another adit from the valley floor, erected drying kilns to reduce the moisture content of the gossanous ore, and also secured a contract to send ore to the Smelting Company of Australia at Dapto near Wollongong.

Construction of a tramway

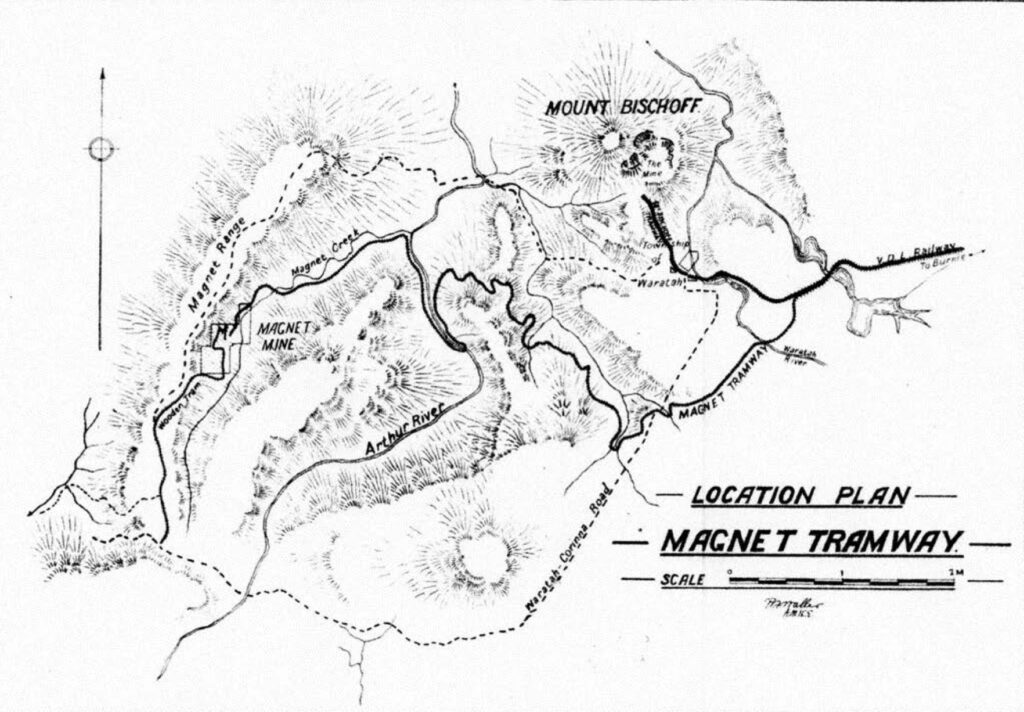

With the scramble to find and exploit the mineral deposits at different isolated locations on the west coast of Tasmania, came the challenge of moving the extracted ore to a port. In the case of the Magnet Range, which had some rich deposits but more numerous pockets of lower-grade ore of iron, manganese, silver and lead, the obvious place to transport the ore was to Waratah with its existing rail to the port at Burnie.

A 23/4-mile horse-drawn tramway was first tried to link with Waratah. It was built up the steep hill above the mine southwards for three miles out to the gravel Corinna Road. The ore was taken on drays for a slow seven-mile trip to Waratah. Apart from an initial steep climb up from the mine, the route was on an easy grade for horsepower. However, as the mine developed, the mine operators quickly realised they needed more power as “such a means of transport was utterly incompetent to deal with the ore available” .

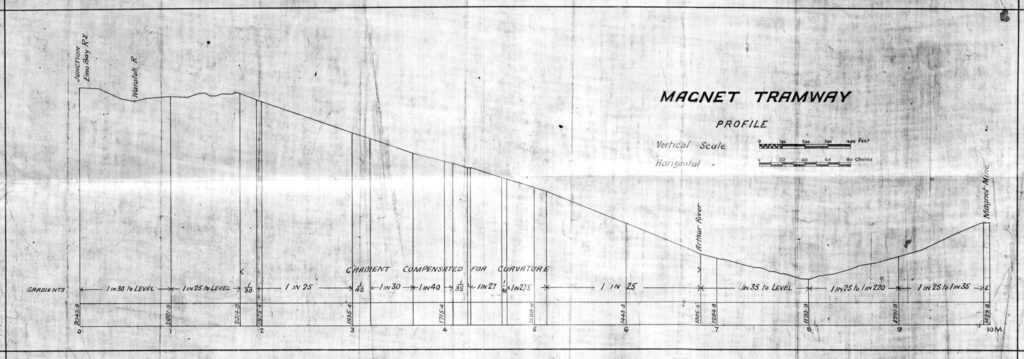

A new proposal was developed to construct a more robust 2-foot gauge steam railway line out of Magnet to a transfer junction on the Waratah section of the Emu Bay Railway (EBR) line. Trial surveys were carried out on two possible routes in 1900, both crossing the Arthur River gorge. They ran down the Magnet Creek valley to turn southwards into the Arthur Gorge, running up its western side to the river crossing. They then climbed steeply back up the eastern side of the gorge before swinging away to the east and south-east up difficult sidling country, meeting easier grades after crossing the Corinna Road. The second option, which crossed further down the river, was shorter at 91/2 miles with a tortuous route of steep grades and tight curves, was eventually chosen as the preferred route.

District Surveyor David Jones conducted a formal survey in 1901, and construction started immediately afterwards. Construction of the tramway occurred under the direction of mine manager Richard Waller. Men were employed on contract for clearing and culvert work, while the remainder of the earthwork was done by day labour.

It was hard work using wheelbarrows, picks and shovels. The line was laid with 30 lb per yard steel rails, sitting on about 22,000 sleepers, many huon pine. It met the 3ft 6in gauge EBR line about 11/2 miles east of Waratah at the Magnet Junction, although it was just a transfer junction with different gauges. Facilities at this point were a shed for two locomotives, a coal stage, a goods shed, a sheltered trans-shipping shed, and two houses for the stationmaster and driver.

The town came alive with two general stores, a post office, schools, churches, halls and a two-storey pub with dangling ropes from the top floor as the fire escape.

Construction of the tramway was completed on 5 December 1901 through wild and steep country. It cost less than the original estimates and was built three months ahead of schedule. Waller’s wife Lucie drove the last spike, and celebrations were held at Ted Lynch’s new Magnet Hotel. James Waller recorded:

“…the Manager’s wife, tiny, neat, pretty as a picture, who had walked the line every day with the Manager, lived in his tent, eaten the same food as the men; knew everyone by his nickname, who was the only woman on the mine…she had an Eton crop and wore a tam-o’-shanter”.

The tramway, snaking through the mountains with a total of 194 chain-and-a-quarter curves, used one of Australia’s few mallet-type locomotives. They were a particular engine built by Orenstein & Koppel with a joint in the middle to enable her to get around the tight curves, four ore wagons and a guard’s brake van. There were 80 tons of ore every trip and two daily trips running ten miles per hour. Other than a crude converted T-model Ford railcar for a period in the 1920s, it never had a formal passenger vehicle.

In his book In Tasmans Land: Gleans and Dreams of the Great North-West, journalist John Sandes eloquently described his trip out to Magnet on the train:

“The train runs for ten miles through the heart of the bush to the mine. The smoke stack on the locomotive is like a huge inverted extinguisher, and a boiler that visibly moves about on the structure. It has a whistle piercing for an engine ten times its size, and the furnace is fed with green timber, that pour out huge clouds of pungent smoke, liberally interspersed with sparks and red hot ashes.

There are four trucks, and the passengers take their seats on a bench placed on the truck nearest to the engine, while the guard, arrayed in oilskins and sou’wester, perches himself on the last truck, in order to devote his best attention to the brakes.

The passengers sit with their backs to the engine, so as not to be blinded by the smoke, and then the steam tram screams like a lost soul in agony, and plunges forward on its narrow track. Swinging round the sidling of a mountain, it dashes down the long gradient towards the bottom of the gorge, where the Ritchie Creek is plashing past the spreading treeferns, and presently it enters upon a long, straight run, cut through the heavy timber that rises on either hand. The gums and myrtles spin past the flying trucks so close that one could touch them with an outstretched hand.

The smoke that pours from the locomotive’s furnace hangs low over the trucks, for steam is shut off, and she is descending by momentum only. The passengers near the front escape the worst of the smoke; nut it streams full in the eyes of the guard, as he keeps his place on the side of the last truck, with a keen look out before him, and a firm hand on the brakes. As he sits there, half seen for a moment through a rift in the driving clouds of smoke, and then obscured altogether until it lifts again, he looks exactly like the steersman of a lifeboat that plunges forward through white-topped seas that gather and burst and part on either side, leaving the helmsman still unharmed. The guard bends his head forward as he crouches down on the truck, and the smoke swings back through the vista of the narrow clearing, and spreads itself into all manner of vague and monstrous shapes between the huge trees – many of them 150 feet high – that wall in the track on both sides. When half the journey is covered, the tram, panting and blowing like a cab-horse that has been driven far and fast, draws up on a little wooden viaduct that spans a creek, and is treated to a needful drink from a tank that is filled from a mountain waterfall”.

The tramway was the only lifeline for the town. Not only did it reduce the transport costs by half, but it was also the only way to get into and out of the town.

Mining the silver

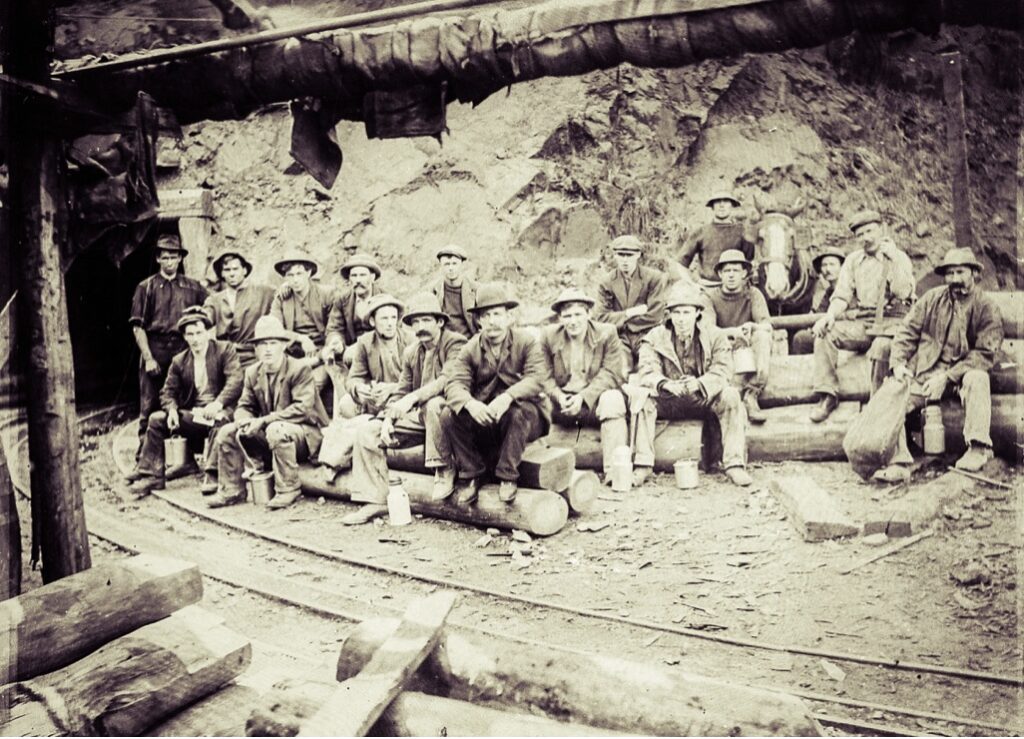

After the new tramway was opened, serious mining started. The horse-drawn wooden tramway limited the production capacity of the mine, but now miners flooded into Magnet, and accommodation was at a premium. They lived in tents or small huts. The huts were 10 feet by 7 feet with split timber walls and a corrugated iron roof. Three men shared the confined space, which had a fireplace at one end, a single and double bunk and a table at the other end.

The mine was on the side of a steep hill. Four adits were driven into its side. The lowest adit went about 500 feet into the side of the hill before it hit the lode. The main levels were all timbered, nearly six feet high and averaged three feet wide. The rails for the ore trucks, which carried almost a ton, ran onto flat sheets of iron at junctions or sharp turns in the mine. They were fitted with a hangar in front, an iron candlestick with one candle, and a strong arm or lever about 14 inches long hooked onto the back and was used for swinging the whole truck around to change direction at a flat sheet.

Empty trucks were walked on the rails and pushed up slight inclines. They were screwed around carefully on a flat sheet and onto the rails again to go in a new direction.

Generally, the town prospered peacefully except on occasions such as payday. There were riotous binges that turned the pub into chaos. Sometimes, men saved their pay to go on a month-long bender to the Melbourne Cup and return broke. Between 1899 and 1913, Magnet fielded an Australian Rules football team in the Waratah District Football Association (WDFA), winning one title in 1907. They tried to get back into the WDFA in 1933 but were unsuccessful. The rejection led to a feeling of resentment by the Magnet community at what they believed was the “unsportsmanlike attitude of Waratah footballers in barring the Magnet Club”. The Magnet club was determined to play football. Surprisingly, the local community created a separate Magnet Football Association competition of three teams called City, Miners and Wanderers, and land was made available at the junction of Magnet Creek and the Arthur Rivers for a football ground.

As mining output increased, the company considered alternatives to treat the low-grade sulphide ores that had been stockpiled. A lead smelter commenced operations at Zeehan in 1899. The option of sending ore to the smelter became viable with the opening of the 78-kilometre extension to the Emu Bay Railway southward to Zeehan. A further contract was signed with the Dapto smelter for the gossanous ore, and the rapidly growing output allowed another contract to smelter ore at Cockle Creek near Newcastle.

Ore sales during 1903 enabled creditors to be repaid, and the first dividend of one shilling was paid to shareholders. However, a dry year in 1905 led to insufficient water supplies to operate the jaw crusher, mine hoisting and pumping equipment. Funds were redirected to construct a 68-megalitre storage dam on the Arthur River and a 1.8-kilometre water race to connect with Seven Mile Creek.

In 1907, there was heavy expenditure on additional mill plant, another Mallet locomotive to handle the increased output, the increased storage capacity of the Arthur River dam to 127 megalitres and electric lighting for the mill and mine. Dividend payments were halted because of the increased expenditure and a downturn in metal prices, as was the eight per cent wage bonus for the mine staff.

Increased water consumption following the switch from steam power led to summer mining shutdowns in 1909 and 1910. With its financial situation deteriorating, the company was forced to raise capital for the first time since its formation. Fortunately, above-average summer rains in 1911 allowed for increased production and a 20 per cent workforce increase. It was offset by increased shipments to Germany after the Zeehan smelter was forced to close after a dispute with its primary supplier, the Hercules mine.

With the outbreak of WWI, production ceased due to the suspension of the ore supply contract with Germany. The company had some money in credit and used most of it to sink a new shaft. Mining resumed, but because working expenses exceeded revenues, the company approached the workers to accept reduced daily wage rates so work could continue. However, the 12 engine drivers who worked under a separate federal award refused the new proposal, and while the situation was temporality solved, it didn’t last. It proved counter-effective anyway, as the government was paying standard rates for labourers employed on road construction and thus, miners were in short supply. Nonetheless, the company’s financial position eventually improved, and dividends resumed, helped by high wartime metal prices.

The water shortage problem reared its head again during the summer of 1913-14. The directors announced at the November 1914 shareholder meeting the construction of a 364 megalitre storage reservoir (No.2 Dam) and the installation of a hydroelectric plant.

The dam took over three years to construct after the upstream face of the dam was lined with sandbags, in the absence of a large rockfill, to protect against wave scour. With water levels rising in the dam, a section of the bagging slipped and blocked the outlet pipe. A diver from Burnie was brought in to clear the submerged bags to allow the dam to be drained. Remedial work followed, and the dam was finally filled during the winter of 1920.

After the war, production was limited by labour shortages. This was exacerbated by the influenza pandemic, which reached Magnet by the beginning of September 1919. Even though no one died, over half the workforce was too sick to work. The Federal government also maintained an embargo on base metal ores until March 1920. Still, the high freight cost to Europe meant overseas exports had to wait until the situation improved significantly.

All production was suspended for 12 months in March 1921 due to a severe downturn in the metal markets. The recovery in metal prices coincided with a dry year, further limiting production as steam power was used to conserve water for essential mine pumping. The Cockle Creek smelter was closed due to reduced output from the Broken Hill mines. However, Port Pirie became feasible after the Electrolytic Zinc Company built a smelter at Risdon on the Derwent River, establishing a shipping route from South Australia to Tasmania.

To deal with continued water supply issues, the dam wall at the No.2 Dam was raised to store 568 megalitres and construct a new water race from the Arthur River. Construction works were delayed after the district received over 21/2 metres of rainfall that year.

Although rainfall in 1924 was above average, and despite both dams being full at the beginning of summer, six weeks later, the hydroelectric power plant was forced to operate on a single shift to conserve water for pumping. After the hydro plant was built, the storage dams were consistently reduced to the reserve level of 38-40 days, consuming 17 megalitres daily or 1-2 megalitres per hour. While it seems logical that alternate sources could be harnessed in such a wet climatic area to prevent critical water shortages during summer, the reality was much different because the rivers to the east were fully utilised by the Mount Bischoff mines and the Whyte River to the west by the Cleveland mine.

The financial success of the mine was mainly due to “careful management and constant production”, even though they did suffer prolonged shutdowns caused by war, smelter stoppages, metal price slumps and water shortages. These all combined to weaken the company’s financial position at a time when increased capital expenditure was required to ensure the profitability of the mine. In 1928, a mining engineer was engaged to undertake trials of zinc recovery from the tailings by flotation, but this required over £15,000 on new equipment. Water shortages continued in the early 1930s, and a proposal to increase the height of the No. 2 dam wall by a further 3 metres was not carried out due to a lack of finance.

Low metal prices during the first ten months of 1932 forced the closure of the mine and the retirement of manager Robert Hales after 20 years of service at Magnet and 52 years in the mining industry. The company went into liquidation.

The end

An agreement was reached between the liquidator and the Magnet Prospecting Syndicate to transfer assets and the mine’s lease as a cooperative venture of 70 employees led by Charles Hugo. The mine was worked under tribute; however, it barely paid its way as the Great Depression took hold. The venture folded at the end of 1934 when water supplies were exhausted during a severe drought in the state’s north-west.

A new Magnet Prospecting Syndicate was formed and armed with subsidies from the government, successfully negotiated with the Mines Department and liquidator to allow mining to recommence at a time when prices for silver and lead were favourable. However, limited production led to another failure and closure of the mine towards the end of 1936. The town’s population dropped to 37, with many houses sold and dismantled.

The following year, a company from Melbourne called Amalgamated Goldfields Estates, one of whose directors was the former chairman of the Magnet Silver Mine Company, provided a substantial budget to refurbish the mine shaft, dismantle the old mill and install new equipment, including electric motors to ensure production continued in summer. While good rain fell in January 1938 to fill the dams, the mine was not operational until mid-August after about £25,000 was spent. The new company entertained prospects of developing a “mother lode”, but that proved a dream as the mine remained unprofitable, and it closed for the final time in March 1940 with 100 tonnes of zinc concentrate unsold.

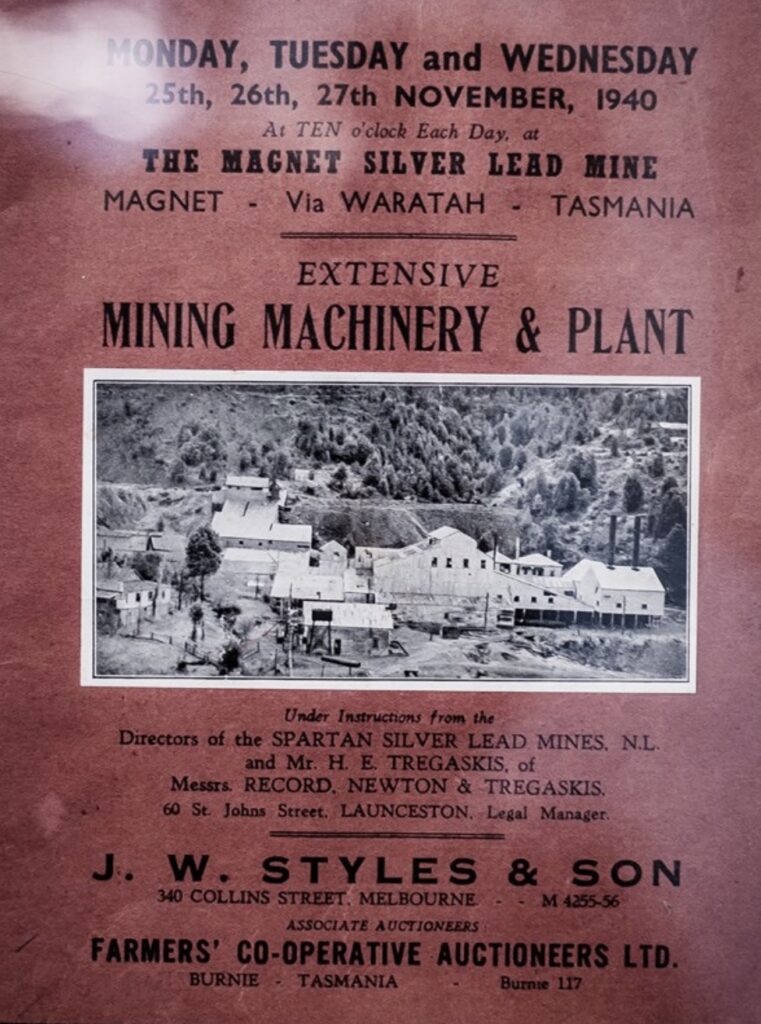

The auction

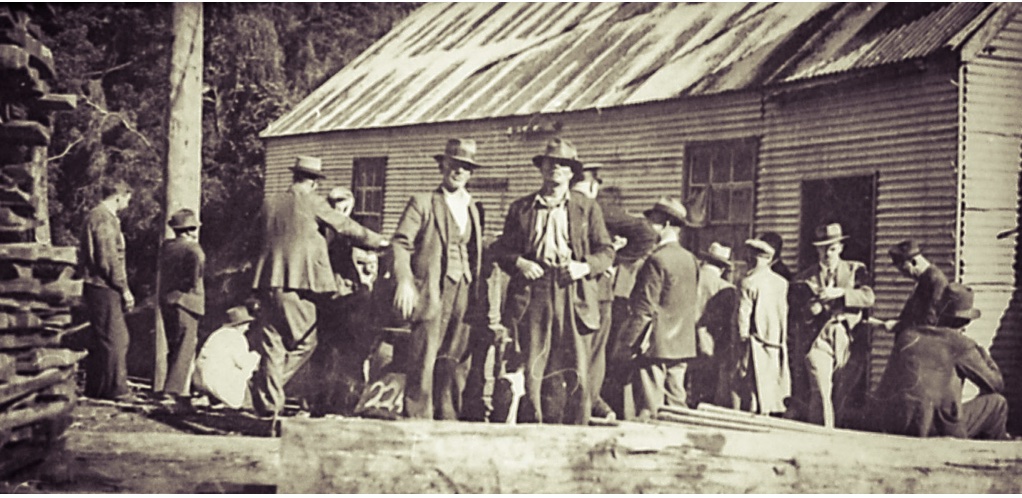

A decision was made to hold an auction to sell all the assets of the town. Nothing was spared. Auctioneers J. W. Styles and Sons arrived from Melbourne on 25 November 1940, numbered the lots and oversaw the sale of 800 lots over the next three days. It was the biggest auction of its kind in Tasmania. Over 150 buyers attended from New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.

Not only was the sale of a complete township by auction unique in Australia, but so was how the buildings were sold. The procedure to auction the 16 mine buildings and miner’s cottages involved the auctioneers, their staff and prospective buyers boarding the mining train, and they were hauled one and a half miles where the train stopped at the building being auctioned. The auctioneer would stand on the engine while the buyers did their bidding from the open trucks.

According to assistant auctioneer Mr Ellis from Burnie:

“It was the most interesting job I have had in my experience. The sale went off without a hitch. Buyers were happy and contented and there were no arguments. In fact, everyone seemed to be in a holiday mood”.

The sale amounted to over £4,000, including the pumping plant, 500 tons of rails, the main mill, flotation plant and electric motors. They even sold the manager’s 8-roomed weatherboard residence and the T Model Ford rail car. According to EBR train driver Robert Morley, timberman Howard of Zeehan shrewdly purchased the railway line and rolling stock for £40-25. As everything had to be taken out via the railway, he charged what he liked and made a killing.

Tasmanian buyers were the successful bidders for at least two-thirds of the plant, and local buyers purchased most of the buildings.

The Catholic Church was built and opened in 1913 by the Archbishop of Hobart. Unfortunately, the weather “was very boisterous,” which prevented many people from attending the opening. After the auction, the church was shifted to Ridgley, and it was a real feat to get it out of the valley in one piece.

It was one of the busiest times for nearby Waratah. All available hotel and boarding house accommodation was booked out. Local businesses flourished, and the fortnightly dance event had never been so popular.

Concluding remarks

While some sectors of the Tasmanian mining industry, such as the Electrolytic Zinc Company and Mount Lyell, were expanding in response to a growing demand for zinc and copper, the settlement of Magnet, a former thriving centre of silver-lead production in Tasmania, disappeared. It amplified the history of the development of the West Coast mining industry, where prosperity and depression occurred side by side.

It is a remarkable story that the isolated Magnet township developed into a thriving community. The steam tramline connecting to Waratah was the town’s lifeblood. It is a surprise that there were constant water shortages in an environment that regularly received well over 2.5 metres of rainfall a year. It was one of the main factors that affected the mine’s profitability.

Factors beyond the mine manager’s control cruelly affected their fortunes. Completing the primary water storage infrastructure in 1921 coincided with a severe metal price slump. In hindsight, an efficient water recycling scheme and the earlier use of electric motors would have ensured the hydroelectric plant could have solely used the stored water and would have maintained profit levels.

The Great Depression was not kind to Magnet and its mill, and later that decade, the decision to re-equip the mill by introducing a costly flotation processing system without any reliable estimate of ore reserves was a big gamble that did not pay off. The new mine managers quickly realised that the higher-grade deposits had been mined. Reworking the tailing dumps for unrecovered zinc failed to save the mine from eventual closure.

In its heyday, the mine was ranked third after Mount Bischoff and Mount Lyell in terms of success and production. By 1923, it produced 6.5 million ounces (184 tonnes) of silver and 27,000 tonnes of lead. It was the largest silver mine in Tasmania until surpassed by the Hellyer mine in the 1990s.

Today, very little remains at Magnet to signify that a flourishing town and mine ever existed.

You have accomplished peak “warp and weft” Robert, with many themes and as always an interesting read.

Merry Christmas!

I would like to echo Andrew Wye’s comments. Merry Xmas!

Another interesting read Robert. That auction was incredible.

Another great story Robert. I found it very interesting. An important part of our local history and a glimpse into how life would have been there in the early 1900s.