“And of course there were ignitions by the fistful. Lightning kindled some fires, but most emanated from a register of casual incendiarists that reads like a roster of rural Australia: settlers, graziers, prospectors, splitters, mineworkers, arsonists, loggers and mill bushmen, hunters looking to drive game, fishermen hoping to open up the scrub around the streams, foresters unable to contain controlled burns, bush residents seeking to ward off wildfire by protective fire, travellers and transients of all kinds. Honey gatherers lit smoking fires. Campers burned to facilitate travel through the thick scrub. Locomotives through out sparks along their tracks. A jackaroo tossed lighted matches alongside a track so that his boss would know where he was. Residents hoping to be hired to fight fires set fires”.

Stephen Pyne “A Burning Bush”

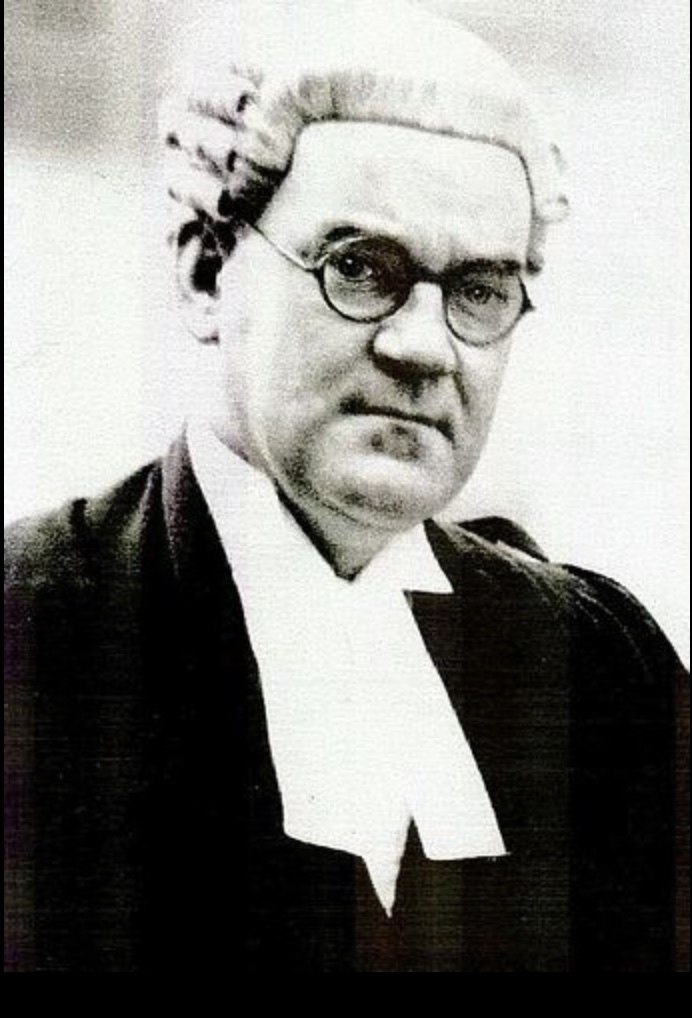

Recently, I read an article that outlined how the Forests Commission of Victoria (FCV) were misguided in blaming graziers for inappropriate fires left uncontrolled into hot summer months before the 1939 Black Friday fires because lightning started most of the wildfires, not “the hand of man” as Royal Commissioner Judge Leonard Stretton wrote.

It has also been argued elsewhere that the forests of East Gippsland escaped large severe fires in the summer of 1938-39 simply because graziers were allowed to continue low intensity burning unhindered on Crown Land that supported their grazing leases.

While the frustrations of graziers about the lack of more broadscale burning by FCV are valid, how some of the graziers dealt with the issue is certainly not justified, as some of the carnage of the Black Friday fires shows.

Burning off was a rural ritual across the landscape, and many fires were lit in the lead up to summer 1938 in country areas. It was done casually to bring on a green pick or for clearing. Sometimes, people would throw a match over their back fence when they saw smoke on the horizon, because a newly burnt home paddock was like a safety blanket.

By the end of October 1938, 27 fires on reserved and protected forests were known and reported to FCV. On 22 November, a proclamation was issued to prohibit lighting fires “in the open” in practically all parts of the state until 31 March of the following year.

A Councillor in the Narracan shire in late December was very worried. Despite the proclamation, he said:

“People were burning off at any time, and they seemed to get away with it and none were prosecuted”.

He provided what turned out to be a prescient forecast when he predicted “fire would sweep the whole countryside” and people who light fires “about Christmas time should be prosecuted”.

Hundreds of small fires, burning since early December, smouldered unattended in the week leading up to Black Friday when, fanned by the gale-force winds, they joined into a massive fire front to create an inferno. Despite the number of fires burning and the severe conditions, some bushmen and graziers lit additional fires to protect themselves – only for these fires to get out of control and spread.

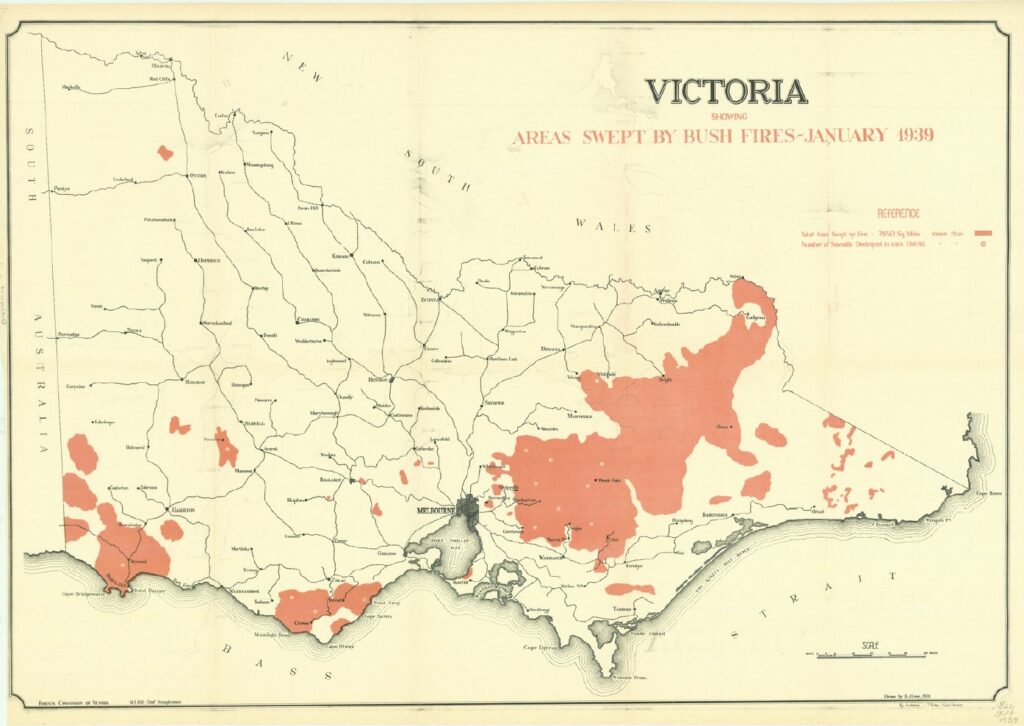

The climax of the 1939 fires was Friday, 13 January – Black Friday. A horror day at the end of a horror week that “sucked 150 years of settlement into a colossal maelstrom of fire”. It remains a seminal point in Australia’s modern environmental history. Even after many fire catastrophes have occurred since 1939, the damage of the Black Friday fires was substantial – 79 people died, townships were obliterated in minutes, 1,300 homes and 69 sawmills burned, and millions of hectares of forests were damaged. The aftermath heralded many subsequent changes in how fire was managed in Victoria and across the nation.

Lightning or the hand of man?

Numerous fires were burning uncontained during December 1938 across Victoria. However, while not uncommon, the conditions were conducive to large blow-up fires. The state was ending a long-running and severe drought period, particularly over the preceding two years. It certainly predisposed the following summer to be very hot and dry. Many creeks and springs had ceased to run. Water storage facilities were depleted. In Melbourne, there were harsh water use restrictions.

Three weeks after the fires ended, Judge Leonard Stretton was selected to hold the Royal Commission to investigate the causes of the 1939 fires in Victoria. He wrote:

“Generally, the numerous fires which during December, in many parts of Victoria, had been burning separately, as they do in any summer, either ‘under control’ as it is falsely and dangerously called, or entirely untended, reached the climax of their intensity and joined forces in a devastating confluence of flame on Friday, 13 of January”.

What were the causes of these “under control” or untended fires? It has been suggested lightning was the leading cause. The article I read indicated that at the Royal Commission, FCV blamed graziers for indiscriminate and careless burning of Crown Land as a foil to gain more bureaucratic power over the Lands Department and gain more areas of state forest. It also challenged Stretton’s famous conclusion that the fires were “lit by the hand of man”.

It is an extraordinary claim that many forest officers or foresters gave evidence under oath and conspired to blame graziers and settlers for the outbreak of the many fires simply to gain some sort of bureaucratic power over the Lands Department. After reading the evidence of these officers, it is highly improbable there is any support for that claim. The simple fact is that many of the forest officers gave evidence of successful convictions against settlers or graziers who were found to have deliberately lit illegal fires.

I searched on Trove for lightning storms between 1 August and 31 December 1938, and any fires from lightning strikes appear to have been in late December after a lot of the country was already alight from unplanned and illegal fires. Unless, of course, the newspapers failed to report any fires started from outbreaks before summer.

An article written in the Argus on 15 November 1937 provides some interesting statistics about fires in Victoria. For the year ending 31 May 1937, out of the 83 fires reported, only two were started by lightning. In the bushfire season to January 1935, only one per cent of fires were triggered by natural causes.

It has also been suggested that people giving evidence at the Royal Commission, other than cattlemen, were loose with the truth. The fact is, Judge Stretton believed many people giving evidence were not wholly truthful, including cattlemen. After reading many of the transcripts of evidence, a lot had a biased opinion on the causes. Stretton, in his final comments, acknowledged this by writing that:

“Much of the evidence was coloured by self-interest…much of it was quite false…little of it was wholly truthful”.

In his findings on the causes of the fires, Stretton wrote:

“No one cause may properly be said to have been the sole cause. The major over-riding cause, which comprises all others, is the indifference which forest fires, as a menace to the interests of us all, have been regarded…Settlers, miners and graziers are the most prolific fire-causing agents. The percentage of fires caused by them far exceeds that of any other class. Their firing is generally deliberate. All other firing is, general, due to carelessness”.

Very little evidence supports the claim that lightning caused the bulk of the fires. While some people say they have proof that lightning caused most fires in the mountains, that is different to claiming the 1939 fires were caused by lightning fires. No one gave evidence to the Royal Commission that lightning was a primary source of fires. Many graziers themselves admitted the fires were deliberately lit.

1939 fires started by lightning

Lightning started a couple of fires. One was on 20 December 1938 in the states north-east. During an electric storm that set the grassland alight very early in the morning of 12 January 1939, lightning started fires in the Keotong hills near Walwa.

Another fire started in the Rubicon State Forest on 7 January 1939 by lightning. Fortunately, firefighters quickly controlled it.

Very experienced East Gippsland forester Moray Douglas wrote on page 105 of his excellent book A History of the Forests and Forestry in East Gippsland:

“…there is nothing to suggest that lightning was a major cause of fires in Eastern Gippsland during this period. It is of significance that no one giving evidence to the 1939 Royal Commission put forward lightning as a major source of fires. With graziers being accused of starting fires, it could be expected they would blame lightning if there was any chance that it was the cause”.

1939 fires started by human causes

James Ezard was a sawmiller who ran a mill on the west bank of the Thomson River near Erica. He told the Royal Commission that people who lived adjacent to the forests started fires near his mill before Christmas. A regular practice was to burn the scrub that encroached on them. “That practice goes on year after year”, he told the Commission. While he supported them doing the burns to remove the build of fuel, Ezard said they “light a fire when it should not be lit, that is in the period of the year when fires are dangerous…nothing is done wilfully…it is more through ignorance…They know other people are burning, and they try to follow suit”.

The question that arises from Ezard’s evidence is why they had to deal with the growth of “scrub” every year on their leases. According to Ezard, “these people had to burn the scrub to live. If they did not burn it, they could not live as the scrub would grow up and they would be wiped out”. As graziers know, one way to get a “growth of scrub” that had to be removed each year is through repeated hot burns. As Ezard claims, the settlers lit fires at an inappropriate time of the year, and they damaged the timber in the Tanjil forest that men like Ezard relied on for their sawmills.

In Stretton’s 1946 Royal Commission into forest grazing, he attributed the extent of scrub growth in the Alps to the cattleman’s use of fire to promote grass.

“With each burning, the growth of scrub was stimulated so that it successfully contended with the grass for possession of the mountain sides”.

Graziers have never agreed with his findings, particularly concerning of grazing impacts in mountainous forest lands. Stretton recommended that all grazing licences should be managed by FCV rather than the Lands Department.

William Lovick, a grazier from Mansfield, had a Crown Lease since 1910 in the mountain country. He argued it was impossible to prevent fires and acknowledged most fires were caused by careless people and “by careful people with insufficient knowledge”. William McCoy, another grazier from Ensay, suggested systematic autumn burning should be carried out under the supervision of a forest ranger who was an experienced bushman.

One of the large fires that devastated the forests of the Great Dividing Range in the Central Highlands began quietly enough on New Year’s Day, 1939. The fire started on private property on the banks of No. 3 Mountain Creek near Kinglake. There were no storms immediately before the fire started. A north wind drove the fire, slowly at first, towards Mount Slide. FCV fought the fire for the next eight days without bringing it under control. FCV employees forester, John Barling, aged 31, and Overseer Charlie Demby, aged 55, were part of a gang of twelve burning from a fire break in the forest when the wind changed direction to a very strong north-westerly at about 1 pm on Sunday 8 January. Barling left the gang to check a section of forest just as the wind changed and drove the fire towards him. Demby ran into the smoke to warn him, and both men were cut off from the rest of the gang by the wall of fire. It was the last time either man was seen alive. Their charred bodies were found the next day. Demby had been carrying Barling on his shoulder to the safety of Gutter Creek when the fire overtook them.

This fire started suspiciously on adjoining private property adjacent to the state forest in the middle of summer, during the worst drought conditions in living memory. It killed two FCV workers doing their jobs. It was not started by lightning. After the wind changed to a westerly and then south-westerly, the fire burned on the elongated north-east flank through the Black Range towards Yea, eventually reaching Narbethong, Healesville and Acheron Way.

On 17 December 1938, prospectors lit a fire in the Toombullup forest, south of Tatong. By 10 January 1939, the fire was burning on a 65-kilometre front and had already burnt 208,000 hectares of forest country, destroying two sawmills. Along with another fire that started behind Myhrree, they swept south of Tolmie highlands towards Whitlands and Moyhu under the influence of a strong northerly. The next day, the Toombullup fire was the largest single fire in the state, devouring half a million acres of forest. On Black Friday, 13 January 1939, all hell broke loose. The fire jumped the Buffalo River and headed towards Mansfield and the Delatite Valley, continuing its rampage until it ran out of fuel north of Woods Point.

Three fires that broke out in the Langwarrin district on 18 December 1938 were believed to have been deliberately lit. The local brigade admitted that fires were lit on days when strong north winds were blowing.

In the Bright-Omeo area, several fires had been burning for a “considerable period,” causing minor damage. But because they had been left to their own devices uncontained, they roared into life when the winds strengthened, and the fires were driven through Crown lands and private property, causing severe damage, which peaked on Black Friday.

FCV Chairman Alfred Galbraith believed every bush fire, except one on the weekend of 7-8 January 1939, was “caused by human agency”. It would be difficult to maintain that position if dry electrical storms had occurred then, but they didn’t.

A fire started on Ernest Owen’s selection at Little River and eventually burnt around the south-eastern side of Mount Buffalo towards the Buckland Valley, killing two people on 21 January. Owens tried to claim the fire started about a mile above his house, even though, according to a forest officer with FCV, the fire couldn’t burn from when he said it started. Constable Duncan and a forest officer saw the remains of a burnt log on his run with “ashes strewn over the track”. When questioned while fighting the escaped fire with other men on 11 January, Owen denied he lit a fire to burn a log on his property. The coroner believed him, finding that “the evidence being insufficient to show how such a fire originated”.

The 1938-39 FCV Annual Report provides clues about the origin of fires. Page 22 lists a table showing that 50 per cent were caused by “grazing interests” or “settlers, landowners and farmers”.

The report scathingly attributes the fire problem to the graziers:

“It is an established fact that grazing interests on Crown lands are responsible each year for a relatively high percentage of fires, and under such circumstances, it is obvious that divided control represents a serious weakness.”

The fact is that people carelessly and selfishly lit fires. They also carelessly and selfishly allowed them to burn. The problem wasn’t isolated to Victoria. In New South Wales, fires started by “some chap on a horse” have been a constant problem on state forests with a grazing lease. My blog about the 1968 fires provides a historical account of the problem in the Bellinger Valley and other places on the north coast. A similar pattern has been experienced in Western Australia, Queensland and Tasmania.

In 1932, Frederic Eggleston, a former minister in the state government, wrote about the short-sighted attitudes of:

“…the grazier who can get grass in the forest if he puts a fire in, and the indiscriminate settlers who cut into the forest as he would into a cheese, wasting most of the timber and leaving the rest as fuel for fires”.

There was another problem that was not solely the grazier’s making. As I highlighted in my blog on the fire history of the Dandenong Mountains, the casual and careless use of fire in backyard incinerators by residents living adjacent to the forest was also a major cause of the fire problems on the mountain.

I need to finish this section by highlighting that the 1939 fires were not solely the fault of careless lighting of fires by graziers. Prospectors, forestry workers, campers and landowners were equally to blame as inappropriate fires were smouldering at sawmills in the bush, campfires were left unattended and domestic fires were allowed to escape.

But to suggest that cattlemen and graziers were exempt from any blame and the fires were instead started by lightning is not supported by any evidence. That, of course, is not to say all graziers were irresponsible with fire. They were not.

East Gippsland in 1939

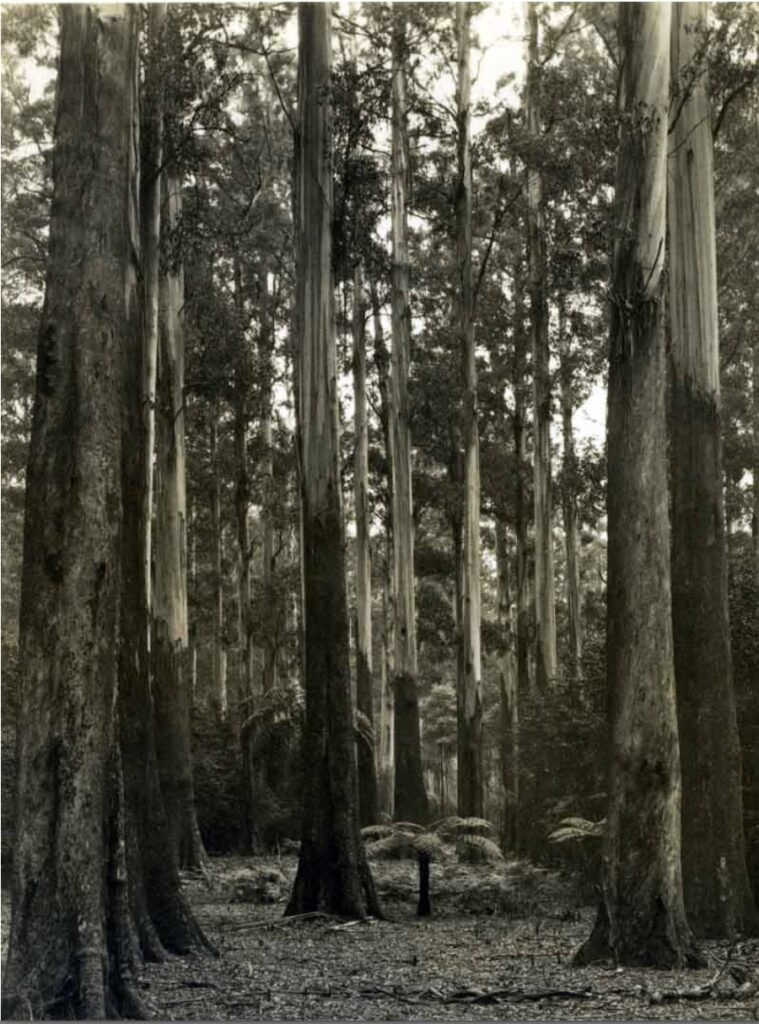

The East Gippsland region is unique in many ways, not least being Australia’s most extensively forested region. With the arrival of Europeans, much of the grassy open woodlands of the plains, tablelands, valleys, and riverine forests were converted to farming land. Fortunately, most of the forests were on soils considered unsuitable for farming, which is why such an extensive forest area exists today.

However, that does not mean they are now in the same condition that faced the earliest European explorers in the region. There was heavy exploitation of the forests for timber, which was unregulated in the early days, with no thought given to a new crop of trees. But, the subtle changes in fire management have also influenced the structure and nature of the forests.

The article I read argued that:

“…the forests along the Great Dividing Range from east of Melbourne through to the New South Border were subject to two different fire regimes. The areas of State Forest had fires excluded as much as possible. The mountainous, isolated areas of Crown Lands to the east of the state were burnt regularly by the mountain cattlemen of the era”.

This is not entirely correct, as while there were large fire outbreaks in 1938-39, they were better controlled in East Gippsland than in other portions of the state. It has been argued that FCV removed cattlemen from state forests with disastrous consequences. However, evidence given during the Royal Commission from graziers shows that the Lands Department was the main culprit. John Findlay, a grazier from Rubicon, had this to say:

“I left the Stockman’s Run about 1920…I think it was the year before I left Stockman’s Run that the Crown Lands Department sent me a paper to sign. The paper stated that I would be fined £25 if I lit a fire. I sent it back and said the run was no good to me if I could not burn it…It was Crown Land”.

On many maps that show the location of the 1939 fires, East Gippsland was nearly free of wildfires. The 1939 fires had a much less impact on the East Gippsland region than the Central Highlands. There are many reasons for this.

One is the accurate mapping of the extent of fire in a vast landscape without roads was impossible, and FCV had little interest in recording fires they didn’t attend. Therefore, the extent of the fires in remote mountains was most likely under reported.

The bad north winds in East Gippsland were not as severe as the higher elevations in the Central Highlands, another factor why the region didn’t have devastating fires. That was also the case during the 2009 fires. Usually, in East Gippsland, a north wind is followed by a howling westerly, often with disastrous results when fighting uncontained fires. In 1939, this did not happen on Monday, Wednesday and Thursday of Black Friday week. There was very little wind, and this greatly facilitated control measures.

There was an unheralded and significant historical event in the East Gippsland area (and other forested areas of the state) during the Great Depression that significantly impacted the East Gippsland forests. It was another factor the area escaped damage from the 1939 fires.

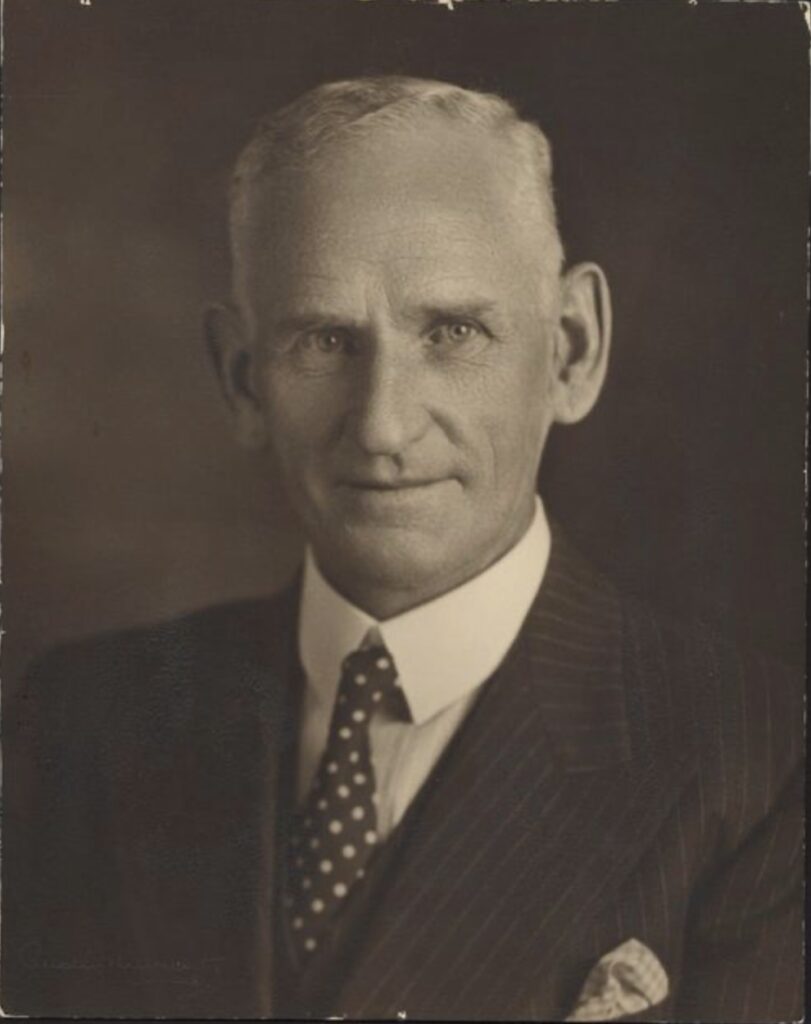

During the Great Depression, the Victorian government was keen to find as much work for unemployed men as possible by setting up relief works by various government departments across the state, administered by the Employment Council. The scheme operated right up to the Black Friday fires. The FCV established relief camps in the forests to employ over 4,500 people in silvicultural work. East Gippsland was fortunate that much more money was spent on fire protection in the forests through the strong support of Mr James Firth, the Divisional Inspector of Forests and Sir Albert Lind, the Minister for Forests and Lands, who owned a 3,500-acre dairy farm at Mount Taylor, about ten kilometres north of Bairnsdale. The property included a substantial area of forest.

From 1932 onwards, the government spent considerable money in the East Gippsland forests. Lind set up forestry camps for unemployed late teenage boys at Mount Taylor, for single men at Beddgood Crossing, and married men on the north side of Mount Taylor. The men lived in rows of tents on beds made from hessian and saplings. There was usually a galvanised iron shed built as the kitchen mess. There were also camps at Noojee and Nowa Nowa.

The Head Office of FCV only approved the expenditure on “regeneration and liberation treatment,” which consisted of silvicultural work, including the ringbarking of all poor-quality trees. They removed all understorey vegetation and raked up and burnt all the forest litter material. They did not approve the expenditure of the unemployed relief funds on road and track work and opposed other controlled burning in the forest.

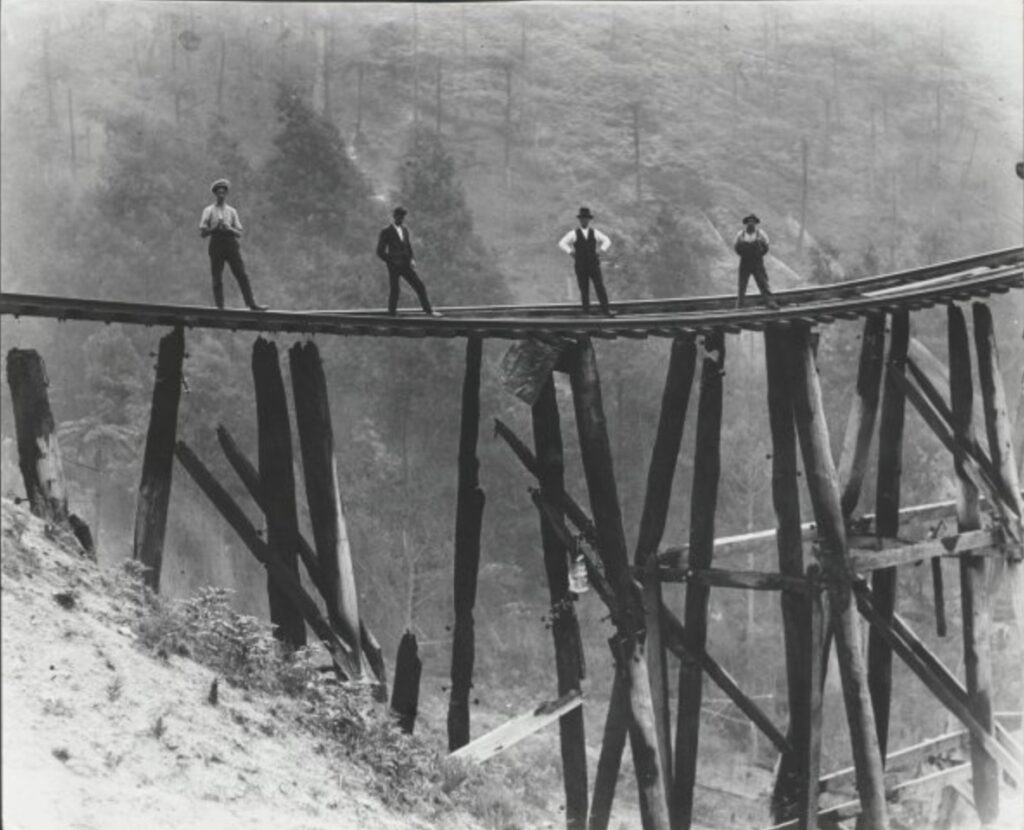

However, Firth argued that the ringbarking of cull trees would only create a fire hazard from the tops of trees, of which sparks could be thrown a great distance if there was a hot bushfire. So, without Head Office approval and knowledge, much of the relief funds were spent in all East Gippsland districts on road and track construction, strategically located in the best forest areas for future fire protection and aided in improved ingress and egress into the forests. The fire breaks were about 15 feet wide.

In 1938, Firth became Chief Inspector and moved to Melbourne. His successor, Herbert Galbraith, who was in Powelltown in 1926 when it was burnt out, agreed with the policy, and the work continued unofficially.

The following is an extract from an unpublished memoir I have in my possession by the late Reg Needham, a forester who worked in the Bruthen and Omeo districts at the time:

“Each year until spring 1938, one side of the new tracks was burned the following spring and autumn, during suitable weather, so that the following summer they would provide safe access for firefighting crews and an effective base from which to back burn”.

The 1937-38 summer in East Gippsland was an awful fire season, and large areas were burnt. There were 291 fires on Crown Land across the state, covering nearly 60,000 hectares. However, the areas treated by the unemployed relief workers and the roadside breaks proved most effective as a base for back burning to stop the bad Black Friday fires the following summer.

Towards the end of 1938, there were many fires in East Gippsland because conditions had been dry from September. A fierce fire surrounded Colquhon on the Orbost rail line in late November. After the train passed the Wygarra railway bridge, the fire was so intense the bridge burst into flames.

On 2 January 1939, fires started in the Orbost and Bruthen districts. The Orbost fire was on Bendoc Road and burnt from Mount Little Bill down to Tom Malinn’s property at Goongerah. Later, during the Black Friday week, this fire struck up again and, with a north-easterly, was driven south-west towards Yalmy and Roger Rivers.

The Bruthen fire was at Mount Alfred. It was stopped and patrolled until 8 January 1939. Contrary to very definite instructions, a further patrol was considered unnecessary by the local FCV foreman. On Sunday, 8 January, with a strong north wind, it spread some miles into private property on the western side of Mount Taylor into the property of Minister Lind. This fire required strong efforts to control, which would not have been possible without the extensive roadside burning carried out in early spring. The fact that firefighters contained the fire through the terrible fire weather days on Tuesday, 10 January and later, on Black Friday, 13 January, indicated the effectiveness of the firebreaks and the strategic burning by FCV.

There were also fires along the New South Wales border, and with the north winds behind them, they burnt into the Errinundra Plateau but were quickly controlled.

At Nowa Nowa, there were fires in Gelantipy and the Murrindal areas and west of Spankers Nob. All these fires were controlled. FCV staff in all districts worked day and night for the entire week.

It is not without contention the low-intensity burns carried out by graziers was very beneficial for the area, but to discredit forestry management as a non-contributor is patently false.

Why the antagonism?

So why was there this battle between foresters and graziers over burning? It is no secret that foresters and cattlemen didn’t get along. Graziers were interested in a green pick and open range for cattle, whereas foresters were concerned about the timber stands – mostly the fire-intolerant younger alpine ash.

In the 1920s and 30s, there was an ongoing fight between settlers and foresters about the use of fire, and each saw the bushfires of 1926, 1932 and 1939 as the result of each other’s malpractice. Settlers and graziers argued their “burning off” helped keep them and their neighbours safe. Foresters, in charge of the timber resource, tried to suppress fire to protect the regrowth trees. There were too few FCV staff leading up to 1939 to regulate illegal burning. While some graziers took precautions against the spread of fires, many didn’t.

Well respected grazier group, the Mountain Cattlemans Association of Victoria has contributed to the debate surrounding past fire management in Victoria. However, they have sometimes glossed over the complexities of government policy and land use issues at the time.

Why didn’t the foresters simply burn more and manage the fuel levels on their estate? It is not as if they didn’t have any fire management policy then. The answers lie in understanding the development of differing management of crown tenures and the delayed introduction of professional forest management.

In the early days, Victoria was unique in its forest composition. Before European settlement, as much as 50 per cent of the state was forested. A further third of the land supported mallee eucalypts, paperbark and wattles. Only about 15 per cent was treeless.

Most, if not all, of the early explorers referred to burning, and in the open forest areas, they described how they rode their horses easily through the area. While Aboriginal land management gradually disappeared, and with it a sophisticated fire management system, Europeans introduced their burning style. Miners or prospectors began the clearing during the gold rush and fired the ground to make it easy to prospect. Paling splitters were the next to attack the forests. Selectors followed, clearing the land with an axe and fire.

The pastoralists, taking up land in settlers’ footsteps, had to carry out improvements. They cleared their runs in forested areas by killing the trees through ringbarking. They could ringbark about four acres a day. They then burnt the debris around the trees they had ringbarked. Over time, they noticed the encroachment of scrub. Their burning approach differed from the Aborigines as they tried to clear the forest and remove the overhead canopy to favour pasture for their stock. The land resisted by producing pioneer shrubs to facilitate the return of forests. Selectors persisted as fire was their only weapon to achieve their goals.

With the clearing of the Strzelecki forests in the 1880s and 90s, fires were burning across the landscape continuously. Some think this burning was part of a strategy to reduce fuel levels – it was no such thing. The fires were mainly hot and deliberately lit to remove large stumps and induce a green pick. They were mostly lit late in spring or early summer when it was much easier to get a decent burn through emerging green vegetation that had sprung up since the tree-clearing operations. The lighter forest grazing burns came later.

Norman Wakefield was a professional naturalist who spent many hours in the bush. He was considered an authority in the flora of the Gippsland and East Gippsland regions and published many articles. He spurned publishing in referred journals, instead supporting the Field Naturalists of Club of Victoria and its journal the Victorian Naturalist. One such article was an outline of burning practices in the northern part of East Gippsland, which was published in 1970.

Wakefield provided a general outline of burning practices by graziers in the Victoria’s Snowy River Valley and areas to the west. Early settlers found open park-like appearance of the forests, conducive to grazing. It became the accepted practice for the grazier’s to burn the bush about every four years in very hot dry weather, usually in January and February, to get a “clean” burn.

By studying the effect of burning in the different forest types, Wakefield found in the dry forests there was vigorous regrowth of trees and several shrubs, and in the dry grassy woodland on the plateau there was regrowth of eucalypts from root stock. It became a vicious cycle as graziers needed to continually burn to remove the scrubby vegetation that proliferated in East Gippsland forests below the high plateaus to support their grazing practices.

Roy Hedger had a lease to run sheep in the high country of New South Wales near Mount Jagungal. He said, “we would never burn bush country as it would make it worse and bring suckers up”. Botanist Richard Helms, who worked in the Snowy Mountains collecting material for the Australian Museum, wrote in 1893:

“A common and in my opinion a very improvident practice, which will probably be continued, is the constant burning of the forest and scrubs. This proceeding has only a temporary beneficial effect in regard to the improvement of the pasture by the springing up of young grass in places so cleared, for after a year or so the scrub and underwood spring up more densely than ever…”

Before the 1898 fires, selectors and graziers believed the forests, including mountain ash, were kept open in the understorey by their regular firing in early spring.

However, the openness of the forests was also associated with the closed canopy of the mature stands of trees. A great example of this in more modern times was the stand of mature mountain ash at Wallaby Creek on the southern edge of the Hume Plateau about 45 kilometres north of Melbourne, believed to have sprung up from a big fire in 1730, before European settlement and before the displacement of Aboriginal burning by European settlement.

Meanwhile, the indiscriminate cutting of timber in Victoria was becoming a problem. It was a Royal Commission in 1897 that set up Victoria for more formal forest conservancy to try and get order in the management of the timber resource, which ultimately led to the creation of a State Forests Department under the Forests Act 1907, despite the strong opposition of grazing interests.

In December 1918, a much more comprehensive Forests Act was passed, creating a Forests Commission of Victoria. The Act gave the Commission the authority to recruit, employ and manage its employees. The major problem they had to face, along with the protection from clearing and systematic management of the native forests, was their protection from fire. They prepared European style working plans that advocated reduced fires to protect young regrowth, a significant issue in the highly productive ash forests, where even the younger trees were susceptible to lighter intensity firing.

While FCV reported that fire management improved, it was based on a policy of protecting the forests from fire. The works concentrated on strategic firebreaks amounting to 3,600 miles and limited burning from them to remove debris and keep them open. This “patch burning” was usually focused on “inferior” forests adjoining more valuable stands and covered over 32,000 acres in 1937-38 and 68,000 acres in 1938-39, unfortunately a small area compared to the total forest estate under their control. Professionally trained foresters, educated overseas, pushed this policy and based their views on fire experience on other continents. They failed to appreciate the unique fire environment in Australia. Unfortunately, the prevailing thought was not to do broadscale burning as “too much burning is not advisable”, and in those days practically impossible anyway.

Superimposed against this were the actions of the graziers. Victoria had a unique system of “reserved” forests, which were the predominant timber-producing areas that had not already been cleared and “protected” forests, mainly vacant Crown land under the authority of the Lands Department.

The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) managed another significant land tenure. They controlled about 120,000 hectares of forested water catchments for Melbourne, predominantly in the highly productive ash forest in the Central Highlands. Since its formation in 1890, it adopted a “closed catchment” policy, which meant no harvesting of timber and no burning.

During the 1939 Royal Commission, the MMBW engineer Alexander Kelso drew upon American scientific sources to argue for a complete fire suppression and exclusion policy that would allow the forest to achieve a climax state with a closed canopy and clean forest floor that would theoretically resist large fires. While the ecological principle of a stable “climax forest”, a popular idea at the time, was debated in the hearings, it was an irrelevant concept for Australian disclimax forests.

The graziers despised the build-up of fuels in forests, regardless of tenure. They also resented the introduction of a proclamation period, which virtually restricted any burning off during the same period across the state, irrespective of the local conditions. They argued the lack of fuel management hindered their ability to graze the forests or threatened the plains in the high country.

So, they took it upon themselves to burn. They strongly asserted they were portrayed as criminals who lit a fire to protect themselves and their properties or to ensure ideal conditions for their stock in the forest. Under the new laws, they had to do it in such a way as to light the fire and make themselves scarce before being seen in the act, essentially leaving a fire out of control.

Their response was to deal with the issue their way. Their attitude to fires was, “people lit fires; it was nobody’s business”. Many experienced bushmen argued that when given the freedom of when to burn under the right conditions, the fire “was under control”. It reduced fuel levels and didn’t cause problems for anyone else.

But that last point was precisely the problem. Alan McArthur summarised the situation in his 1962 booklet Control Burning in Eucalypt Forests:

“In the main, old-time graziers lit their fires during weather conditions which ensured a good slow burn over the forest floor and alpine grassland and did minimum damage to timber. The lack of adequate control lines meant that no area restriction was placed on the burn and large scale fires resulted when weather conditions deteriorated”.

Graziers made burning look straightforward simply because all some did was light the fire. They never patrolled their fires. They didn’t worry about where the fire headed or went into another tenure. Many never ensured it was within contained lines or checked to see if it was wholly extinguished. Consequently, when lighting in late spring, their fire could easily flare up when dry and windy conditions came. And they did.

This attitude of some graziers only made FCV concentrate more and more resources on preventing fires. Fire protection priorities at the time were maintaining all tracks and fire lines, burning debris, particularly the tree heads from logging operations, and reducing the dangerous litter in the forest, mainly along tracks. FCV had limited funds to carry out these works on all the reserved forests as it had insufficient staff and a lack of independent control over its finances. They could not carry out more widespread burning that the graziers and selectors wanted to see, particularly over the protected vacant Crown lands.

In those days, fighting fires was very rudimentary. While FCV had control of fires within state forests, protected Crown lands and a certain distance close to forested areas on private property, they relied heavily on residents and farmers to fight fires as their numbers were minimal. The latter were called bushfire brigades, but that was a very loose term in those days as they were not formally organised or supported. The primary way they fought fires was with axes, raking and burning back, and where water was available, haversacks: there were no aircraft, tankers and slip-on units. However, under these arrangements, no responsibility was assumed for large areas of mainly inaccessible public land. Foresters were years away from developing an appropriate broadscale fire management system necessary to deal with the fire environment in the country. This showed with large fires in 1918, 1926, 1932 and 1939.

But to be fair to FCV, their fire prevention system was achievable only if they could prevent the fires that started outside their sphere of influence. Grazing licences on protected Crown land were issued by the Lands Department, which was an administrative organisation, not a land manager. They had no policy to deal with or prevent fires. Once they got their licence, the graziers had a free reign to do their burning. While FCV could attend fires on protected Crown land to either control or put them out, they had no power to carry out fire protection works or fuel management on those lands. Nor could they have any control over grazing leases.

Graziers have tried to rewrite history by trying to sheet the whole blame of the 1939 holocaust on foresters and remove any accountability for the effects of the fires they let run under the guise that they were always “under control”.

The 1939 indiscriminate burning problems are not unique to Victoria, the high country or even that time. Every forester in every state has a story about chasing fires during the fire season that were lit indiscriminately and left to burn on their own accord.

Stretton’s legacy

FCV strongly believed their strategy of fire prevention was working. In its 1937-38 Annual Report, they wrote:

“Despite hazardous conditions which prevailed over a long period, damage to forest reserves by fire was confined to a relatively small area. This is particularly gratifying and is an indication that the intensive fire protection organisation now in operation is proving effective”.

However, considering the events less than a year later, their summation proved fatally wrong. Stretton took aim at FCV in his report on the 1939 fires, arguing that responsible officials had refused to use burning as a preventative method on a scale that would reduce the impact of significant fires. In essence, foresters had sought to protect forests from settlement fires, not settlements from forest fires.

I could write a separate blog on the influence of Stretton’s 1939 Royal Commission’s findings (as well as the Royal Commission he chaired after the 1944 fires). However, suffice it to say he supported fuel reduction burning to minimise the fire risk.

Despite the criticism and admonishment, FCV was still recognised as the premier force in using and controlling fire. After 1939, they were responsible for fire protection on all public lands, plus a buffer extending one mile beyond their boundaries onto private land.

Galbraith responded immediately, appointing a new Fire Chief to rebuild a highly organised and effective firefighting force to meet the new challenges placed upon them. But more importantly, FCV obtained additional funding. Alf Lawrence, the new fire chief, invested in heavy machinery, expanded the roading and trial network, built fire dams and installed a state-wide radio communications system. These were the precursors for developing sophisticated aerial operations to introduce broadscale burning as an effective fuel management system across the state.

In essence, the rough, uncoordinated, haphazard and loosely applied active fuel management attempts by the graziers and settlers were, in time, replaced with a much more coordinated program enacted by highly trained specialists and workforce. According to retired Victorian forester and historian Peter McHugh, “both the Forests Commission and the Country Fire Authority adopted clear policies to detect and suppress all bushfires and became very focused and skilled at doing it”.

The mountainous and vast broken country found in Victoria, exposed to the world’s most ferocious fire weather when it arrived, provided a considerable challenge for anyone to tame. With the constraints that a European landscape provides with rectilinear cadastral boundaries and immense numbers of valuable assets that needed protection, it is a credit to FCV that they developed an entirely professional firefighting force and management system that reached its apex at the end of the 1990s.

Stretton’s 1939 Royal Commission forced a new direction and more discipline to the common practice of lighting fires outside of summer and within containment lines.

The quotes need the source stated.

“Fire” – especially in SE Australia (incl. Tasmania) is a very depressing story. Earlier this century, I undertook a research study on this topic. Authors such as Stephen Pyne, Bill Gammage, Leonard Stretton and many more seemed to me to have proposed the most objective recommendations on how to manage FIRE, but it STILL seems to me that the ‘authorities” and the public remain ignorant of those recommendations. DEPRESSING!

Almost without fail every “bushfire inquiry/report” recommendations, invariably echo some or all of some of those contained within Stretton’s Report.

The information within “The Burning Bush”, “The Greatest Estate on Earth”, “Bushfires in Australia” and other publications and reports are not diluted by the passing of time.

Australia is a continent where one Genus has ruled the landscape and Pyne’s comment regarding the eucalypts and fire is one that needs to be impressed on every Australian.

I grew up in Sydney but left it 60 years ago to manage native forests for production ranging from the far north-east of NSW to the Murray River in far south-west of NSW.

Sydney lives on the arable soils and recreates in the woodlands predominantly on the Hawkesbury sandstones. As the population of Sydney has grown so has the frequency of fires in the surrounding conservation reserves. A personal opinion is that as the frequency of wildfire has increased so has the undergrowth changed and it is often no longer dominated by those species that rely on fire for their regeneration.

The frequency of wildfire appears to me to be closely related to population pressure, be that due to accidental, careless, or purposeful ignition. Unfortunately, its timing is not the same as it was previously.

Some years ago on a conference field trip to North Tiers in Tasmania, reference was made to the aborigines hunting in the forest we were looking at. I made comment that the undergrowth was too dense to hunt with boomerang or spear. The response was that 200 years ago this forest’s understory was open grassy, the dense undergrowth was confined to stream banks. Exclusion of frequent fire had resulted in the undergrowth spreading away from the stream banks.

In the hills above Yarra Junction, east of Melbourne, I have noticed the dense undergrowth right to the edge of the road. If those roadsides were hazard reduced on alternate years might not the roadsides be grassy and the trees at risk of burning and falling across the road be gone?

As District Forester Glen Innes on the NSW New England Tableland, we hazard reduced 40 metres either side of the Gwyder Highway through the State Forest in alternate years. However, the aging President of Severn Shire reminisced that as a young man he had galloped a horse through the forest before the highway was built. Today, due to the undergrowth, it would be difficult to walk a horse through that forest.

On the Murray River the River Red Gum invaded a human habitat about 6,000 years ago despite the aborigines frequent using fire. We have excluded fire from those forests. Each flood in the last 200 years has buried forest litter in silt. To burn today you risk igniting the buried silt which will steadily spread cooking the roots and killing any trees it encounters. Hence to reinstate the aboriginal use of fire stands to kill many of the current forest trees.

We can speculate on just how and when the aborigines used fire but that local knowledge is long gone. It is a practice that we can relearn by educated guess and by trial and error. In the process we may have to experience a significant degree of transient damage.

I am afraid that blaming lightning is a way of shifting blame rather than a statement of fact. While the conservation movement cares for “the bush” their track record of looking after “the bush” leaves a lot to be desired. What was productive forest is now burning far more intensely now it is in a conservation reserve!