Introduction

In my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, I dedicated a chapter to outline the construction of a horse-drawn wooden tramway in the mid-late 1870s. The chapter focused on the monumental task of constructing 74 kilometres of a new line through some sections of dense rainforest, all cleared by hand.

As I wrote in the book, I believe it is the longest wooden tramway built in the world. But it was costly to operate. No sooner was the tramway finished than the wooden rails required replacing. Feeding and maintaining the horses was also very expensive. The tramway lasted only seven years before the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co). completed an upgrade to steel rails and steam locomotives in July 1884.

Immediately after that conversion, the VDL Co. saw operating expenses drop by 40 per cent even though gross revenue only marginally increased. However, that didn’t last long, and by 1887, expenditures had risen to the same level as the previous tramway. The high interest on debenture loans for the railway compounded the problem, and any profit gained had to pay the mortgages on the capital raised.

A separate railway company

In July 1887, the VDL Co. announced it would separate its railway operations from its general land and farming business. It was also an exercise in rearranging its debenture debt as existing mortgages used its land holdings as collateral, thus impeding any proposed dealings in their land, particularly land sales.

At an Extraordinary General Meeting on 22 June that year in London, shareholders sanctioned the sale of the railway and its equipment to a separate company for £175,000.

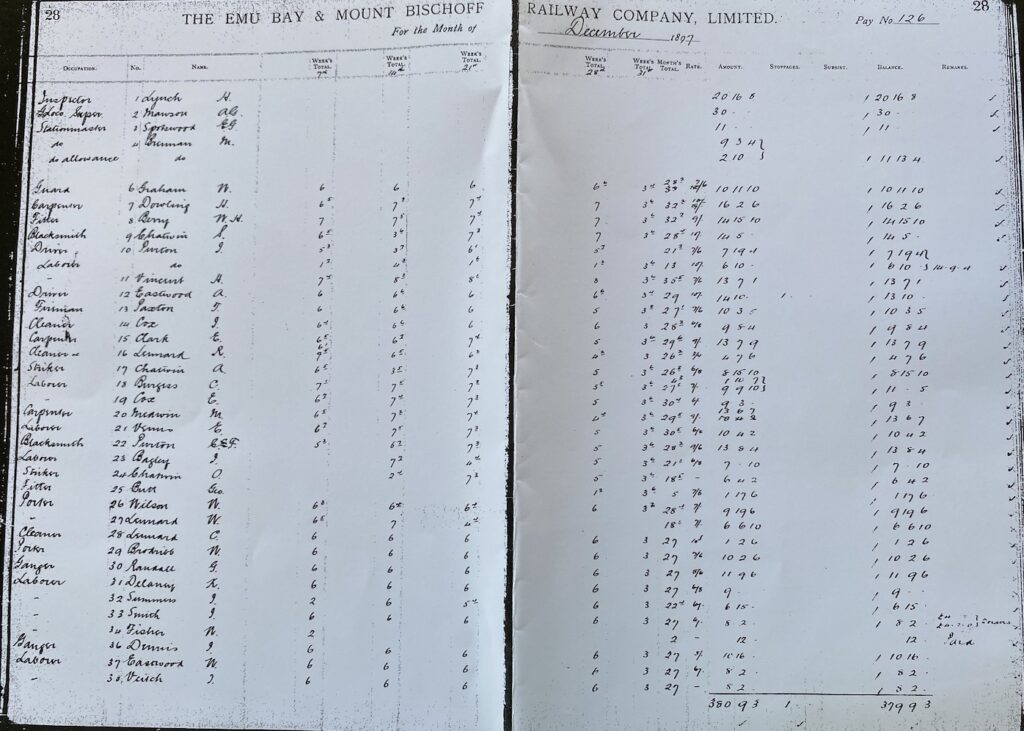

Shareholders agreed to form the Emu Bay and Mount Bischoff Railway Company Limited (EBMBR Co.) at the meeting. Its capital comprised £60,000 in 12,000 shares at five pounds each. The rest was made up of debenture stock at 4.5 per cent interest. Following the offer to shareholders, a prospectus was issued to the public to raise funds and was fully subscribed. It allowed VDL Co. to pay off its mortgage debts and provide capital for dividends and other capital improvements on its properties.

The EBMBR Co. faced the same problems as its predecessor. The amount of traffic changed little while the maintenance costs steadily increased. There was little development in the mining fields around Waratah. The small railway profits ceased repaying the interest on the debentures, which became a significant financial hurdle for the new company.

There was much mining exploration and some activity south and west of Waratah. Prospectors found tin in the Mount Heemskirk area and alluvial gold in the tributaries of the Pieman River. Workers associated with these finds used walking tracks from Waratah, which meant travel was slow, and businesses could send very little mining equipment to these areas.

As EBMBR Co. needed to find alternate sources of revenue for the railway line, they offered discounted rates to new mines to assist in their establishment and development. Still, no mines of significance were located close enough to the railway line to use it and take up the offer.

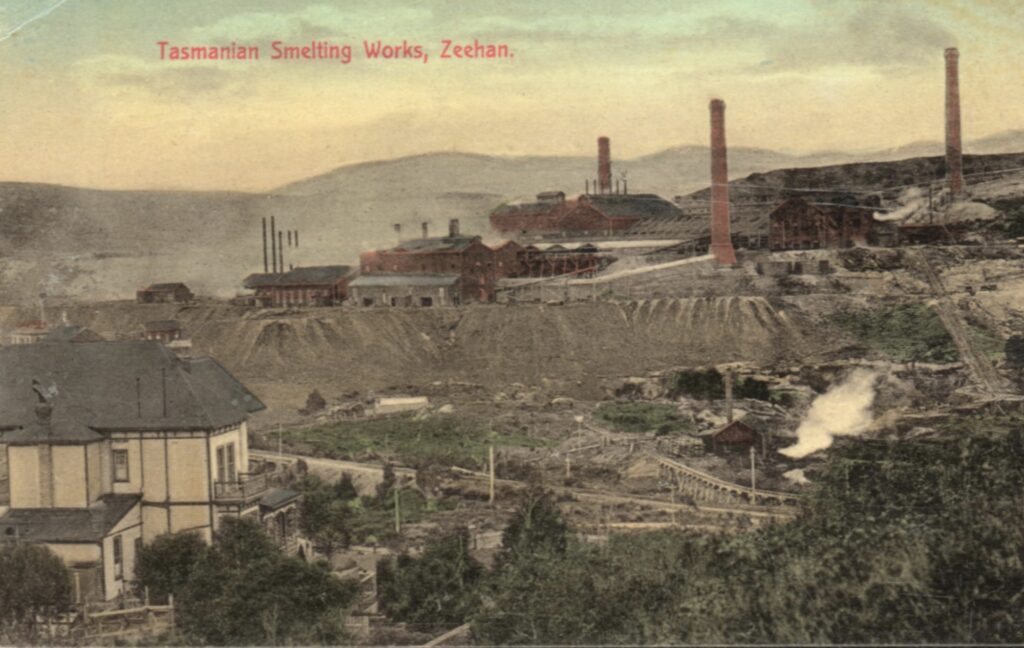

Mineral discoveries in the Zeehan area

Not until a group of prospectors from Launceston discovered a galena of lead and silver in 1882 at Mount Zeehan did fortunes change for both the EBMBR and VDL Comapnies.

The initial discovery failed to attract much interest, mainly because of the high lead content and meagre lead prices. Sporadic prospecting of the area continued over the next five years without generating any significant finds of interest. However, things changed after the massive investment in Broken Hills shares, precipitating a mining boom and attracting worldwide attention.

Suddenly, the interest in the silver at Zeehan and Dundas fields reached a fever pitch. Added to that was a report released in April 1885 by the Inspector of Mines, Gustav Thureau. Virtually overnight, companies were floated, and speculators snapped up the shares. By 1888, 24,000 acres were pegged and leased. As more and more ore deposits were proven with all this prospecting, access to the area was a major hurdle. The only way to bring heavy machinery to start mining was via a boggy, rudimentary 12-mile track from Trial Harbour, which itself was open to the wind and waves off the Southern Ocean. Any vessels using this harbour had to be careful not to end up on the rocks and usually had to wait at sea until the seas and wind subsided. While investors agitated for a railway to the Zeehan and Dundas fields and applied pressure on the government to build it, the one difficulty was the lack of a decent port to ship the ore safely and efficiently.

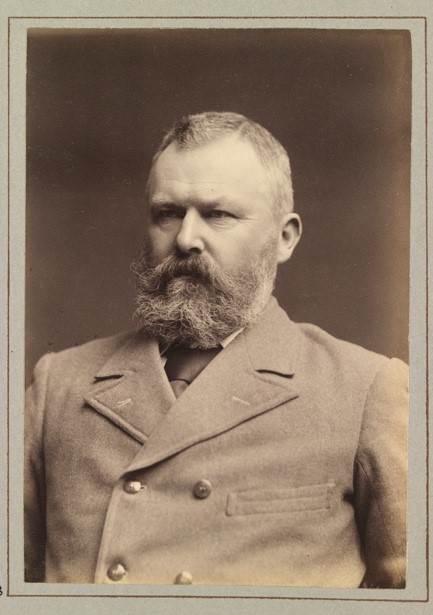

This situation didn’t go unnoticed by the VDL Co’s Chief Agent, James Norton Smith. He visited the mineral fields several times. Seeing firsthand an opportunity for the railway business, he sent a telegram to the Court of Directors in London in November 1888 seeking permission to spend £500 on a trial survey of a railway line between Waratah and Zeehan.

Their immediate response was to wait for further development of the deposits. However, they asked Norton smith to approach Parliament and get and enabling bill passed to allow EBMBR Co. to build a railway. The reasons for this were twofold. One was the VDL Co. didn’t own lan on the west mineral fields beyond the southern Surrey Hills boundary, and secondly, it would add potential value to the railway should they decide to sell. Unfortunately, nothing came of Norton Smith’s enquiries.

A race to build a new line

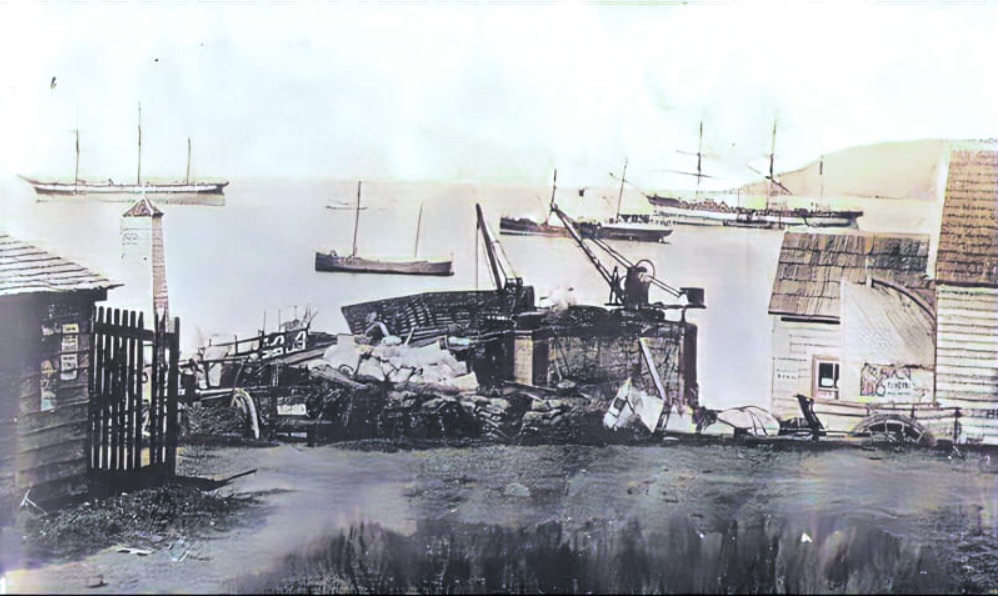

Meanwhile, a race to access the Zeehan fields began in earnest. While there was serious interest from a Hobart syndicate, the only two ports that could service the western mineral fields were Strahan via Macquarie Harbour and Emu Bay. The former had a few advantages, including a closer proximity to the mines and a sheltered harbour. However, access into the harbour was fraught with hazards, namely the narrow and shallow passage at the entrance, called the Hells Gates. It was hazardous for shipping because of the shallow draught over a sand bar and a strong tidal rip.

Emu Bay had, by this time, well-established facilities serviced by a railway to Waratah. Work was already underway to construct a new breakwater pier to improve its shipping trade. However, it was a long way from Zeehan, and there were concerns about the high freight rates on the railway.

Macquarie Harbour became a front-runner to service the western mineral fields when a Victorian syndicate sought approval to build a 2-foot railway line between Strachan and Zeehan for £70,000. However, the proposal lapsed when the surveyor struggled to find a suitable route.

In early 1889, Parliament authorised a survey for a railway line between Mount Zeehan, the centre of the discovered galena deposits on the west coast, and Macquarie Harbour and allocated £60,000 to construct a railway between the two locations. The government passed the Zeehan Railway Construction Act on 4 February 1889 to support the work. Work on the new 51-kilometre railway began and was completed in 1892.

Meanwhile, over the next few years, the financial situation of EBMBR Co. became acute when they were forced to spend a lot of capital replacing bridges and sleepers on its existing railway. The Court of Directors feared the company might not survive and requested Norton Smith to make a formal approach to the government for a land grant to extend their railway line to the Mount Zeehan district and a branch line to the Heazlewood and Whyte River fields.

At the same time, in late 1890, extensive fields of galena were discovered in the Dundas area, further enhancing the long-term prospects of the western mineral fields. However, the reality of the VDL Co.’s financial situation failed to improve the spirits of the directors. They struggled to meet interest payments on their £130,200 debenture issue, and they knew they lacked the resources to spend on any railway survey.

At that time, Norton Smith was approached by a syndicate made up of James Smith Reid, Charles Gibson Millar and William Jones, seeking an option to purchase the VDL Co. railway. Both parties entered into an agreement, dated September 1891, that empowered the syndicate to construct a railway across Surrey Hills toward Mount Zeehan. The plan was to extend the Emu Bay Mount Bischoff Railway on the east side of the Hellyer River.

On the other hand, the government responded to Norton Smith’s approach regarding a railway stating that the railway line the government was constructing to link with Strahan adequately serviced the developing Zeehan fields and “it would not be in the government’s interests to approve the land grant to a potential competitor”. It put a sudden halt to any plans for railway extensions by the VDL Co.

At a more macro level, however, the correspondence precipitated a railway war over the next 20 years. Typical parochial arguments went to another level with claims of government corruption, resignations and threats to vote against the premier. Various consortiums sought enabling acts, including for Launceston’s and Hobart’s interests. The third prominent syndicate was Reid’s Melbourne-based one, which was interested in the Emu Bay Railway line. While the syndicates got what they wanted from the government, they couldn’t start the next step. Meanwhile, new ore reserves were discovered in the Rosebery, Mount Read, Mount Tyndall, North East Dundas (later called Williamsford) and Mount Lyell areas. While railways were built to Zeehan, Dundas, North Dundas and Mount Lyell with proven ore deposits, most areas still had no railway access.

Norton Smith discovered that one of the major opposers to their railway plans was the Dundas and Zeehan Railway Company (DZR Co.). After meeting with the directors, he convinced them to withdraw their opposition if the VDL Co. built their southern terminus at DZR Co.’s Leslie station and then used the DZR Co. line to Zeehan.

Not long after, in May 1893, the extraordinary general meeting of the shareholders of the DZR Co. authorised directors to sell the whole business. Norton Smith recommended that if the VDL Co. built the railway extension, they should buy that railway as it was well constructed and, for about five miles, ran parallel to the Great Northern Railway survey. Besides saving the cost of building five miles of line, it would command the Dundas traffic. Meanwhile, a newspaper reported another effort to connect Hobart via Ouse Valley and Zeehan by rail.

In June 1895, the VDL Co. once again sought an enabling bill from Parliament to extend their railway to Zeehan. They were confident in a large amount of mining investment and were attracted to the prospect of receiving mineral grants of land along the new line. Once again, there was strong opposition from interests based out of Launceston and Hobart. Also, the General Manager of the Tasmanian Government Railways, which was building another line extending from Zeehan to Rosebery (the North East Dundas line), believed if the VDL Co. were allowed to put a line into the south of Rosebery, then the whole traffic would be theirs and the government lines would be useless.

And that was VDL Co.’s intention all along. If the railway to Zeehan was constructed, it would capture all the passenger traffic for the district, the whole of the mineral traffic as far south as North Dundas and Mount Read, and the meat and general produce traffic as the extra shipping facilities at Emu Bay would counterbalance the shorter railway carriage to Strahan. The Zeehan and Dundas railway, which ran parallel to the surveyed line for the Great Northern Railway five miles out of Zeehan, has already been constructed.

The eventual go-ahead

For the VDL Co., the railway extension became an all-consuming priority. For the land company, it would lead to the establishment of Burnie town and, thus a significant increase in their landholdings; for the railway company, the prospect of regular dividends and a profitable sale in the future would remove its debt.

Norton Smith believed a railway connecting Lyell to the VDL Co. bridge at Mackintosh could be built for considerably less cost than a railway connecting Lyell with Strahan. He believed the Mount Lyell company should be encouraged to be shareholders in the railway to give them a share of the profits and to dissuade the development of Macquarie Harbour as a competitor with Emu Bay.

In 1891, a government survey of a railway between Waratah and Zeehan was conducted. The engineer wrote:

“He is of opinion that there will be no difficulty in selecting a favourable line of Country for railway construction over any of the country between the EBMB Railway and Zeehan”.

However, they were competing with interests from Hobart and Launceston that wanted to see a railway link from their cities to the west coast.

Norton Smith visited the Dundas and Zeehan silver fields in early 1891. He wrote that the lode discoveries at Zeehan and Dundas “were marvellous,” anticipating a population of 20-30,000 in that uninhabited country within three years. He stressed a need for a connection between that area and Emu Bay by some means, and if they couldn’t sell the railway, they should take immediate steps to extend it to Dundas and Zeehan. Railway traffic was breaking records at the time, and the “future outlook for the railway was more encouraging than it has been for some time”.

Norton Smith wrote to the VDL Co. Secretary William Brookes in March 1893 that if the Government Geologist Alexander Montgomery’s report on the Zeehan and surrounding district mining fields proved favourable, the VDL Co. could undertake the railway extension work themselves, provided it was found to be impossible to float another company to do the work. His doubts about its profitability were the risk of silver price decreasing to an unprofitable point and the construction of a first-class port at Macquarie Harbour. In his report, Montgomery wrote that there was a considerable mineral field on both sides of the Mackintosh River, through which the railway would pass.

On 24 October 1895, the government passed the VDL Co.’s Waratah to Zeehan Railway Act. The act specified that construction of the 3 foot 6 inch gauge railway must commence within 12 months and be completed within three and a half years. The line was to start from or near Waratah and join the Dundas Railway within a mile of Leslie Junction. The VDL Co. had to lodge a £5,000 deposit within six months of the act coming into force. Otherwise, the act would lapse.

Not surprisingly, the VDL Co. couldn’t fund the construction themselves and looked for financial support from investors without any luck. Reluctant to pay any deposit without external financial backing, their act lapsed. Strictly speaking, the original land charter for the company prevented them from funding improvements or works outside their land anyway, so they had to find investors to build the railway.

They tried to form a new company called The North Western Railway of Tasmania and raise the finance from a prospectus selling shares and debentures. However, that failed to attract sufficient interest, and the company never formed.

Not to be beaten, a Special General Meeting in April 1896 passed two resolutions. The Court of Directors were authorised to sell all the VDL Co. rights associated with the proposed new railway. The Surrey Hills block could be sold to finance the line’s construction if they could not sell the rights.

They applied to the government for a new act as they were now ready to construct the railway line, and they possessed the £5,000 deposit. An amending Act was passed in August 1896.

Two months later, The Great Western Railway and Electric Ore Reduction Company Act was passed for the syndicate based out of Hobart. This proposal showed real competition to the VDL Co’s. plans, and they desperately needed a syndicate to purchase the concessions under their act.

In September 1896, Norton Smith wrote to the Minister for Lands and Works, Alfred Pillinger, seeking an additional lease of Crown Land, one chain in width, to construct a branch line to Mount Lyell, which was given a favourable response.

In the meantime, the General Manager of Tasmanian Government Railways prepared a scheme to connect their Zeehan railway with their primary system at Mole Creek. If successful, it would prevent Burnie from deriving any economic benefits from developing the west coast mineral fields. Added to that was the determination of entrepreneurs associated with the Mount Lyell mine to make strenuous efforts to deepen the bar of Macquarie Harbour.

The syndicate of Reid and Millar, which had previously paid and forfeited a £10,000 deposit to the EBMBR Co. in 1891, signed another agreement with the VDL Co. in August 1897 to build the railway to Zeehan. Reid had acquired much railway experience with his involvement in several railways, including the highly profitable Silverton Tramway serving the mineral fields near Broken Hill. Access to the port facilities at Burnie (formerly Emu Bay) was critical, and he managed to obtain a 99-year lease at £370 per annum with an option to purchase foreshore land from the VDL Co.

However, continued delays in floating a company to start railway construction were a concern. Norton Smith knew Parliament would not look favourably on any request to extend the date to commence operations.

During May 1897, there were verbal indications that The Great Northern Railway Company had been floated in England. In late July, it was confirmed that “a formal start” had been made in the railway construction. This consisted of an exploratory survey to comply with the act.

At an Extraordinary General Meeting in August 1897, the VDL Co. agreed to form a new company called the Emu Bay Railway Company (EBR Co.) with Reid. Reid attracted the interest of Bowes Kelly, who was chairman of the Mount Lyell Company, and William Jamieson, a director of the same company. Both became directors of EBR Co. and Reid and Millar transferred their rights acquired from the VDL Co. to the new company. The primary purpose of the EBR Co. was to offer shares and provide the capital to build the railway.

Reid decided to delay the issue of a prospectus until after the summer in the northern hemisphere. Norton Smith wanted to begin construction work to keep the enabling act alive. Reid asked him to take temporary charge of operations, and he did so without any supervision on the ground.

The prospectus was finally issued in late September 1897, which included plans to connect to the Mount Lyell field. Members of the Great Western Railway syndicate were not impressed, and a furore erupted, especially since there was no mention of any Mount Lyell connection in the enabling act.

The Mount Lyell Company already had a railway line to its port at Teepookana on the banks of the King River and was toying with extending the line to Strahan when finances improved. Additionally, plans by the North Mount Lyell Company to construct a railway to Kelly Basin on Macquarie Harbour and the Great Western Railway syndicate knew their chances of adding a fourth railway line competing for the same resource was virtually impossible.

With the controversy over the western railway construction receiving plenty of press, the application of shares was overwhelming, as most believed the railway would be built to the “mountain of copper” at Mount Lyell. The 150,000 shares were quickly sold, and the railway construction finally seemed inevitable.

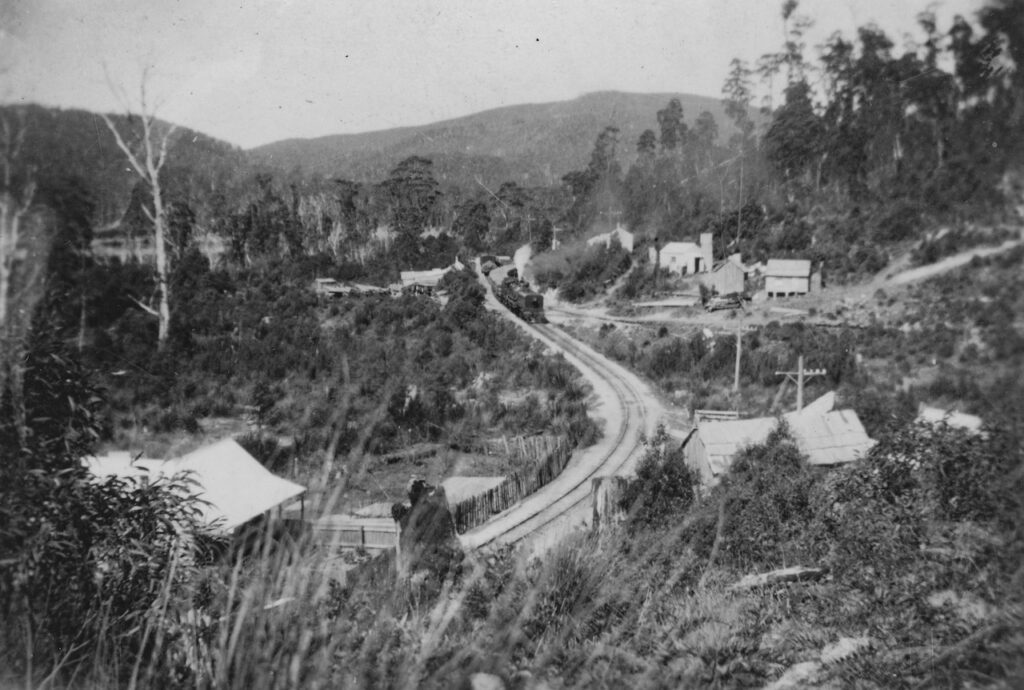

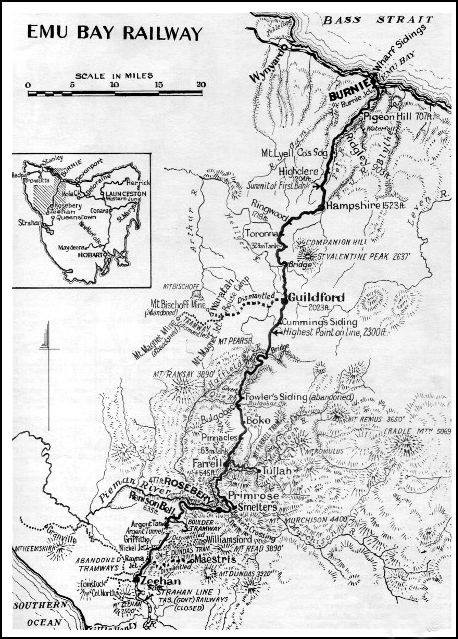

It was decided the northern terminus, or the start of the new railway line, would branch off the existing Waratah railway line near the 37-Mile, initially called “The Junction”. After a station was erected, it was later named Guildford Junction. A triangular junction was built north of the station to enable continued travel to Waratah from either direction. The ten-mile length of the railway line linking Guildford and Waratah became known as the Waratah branch line.

Construction of the new line

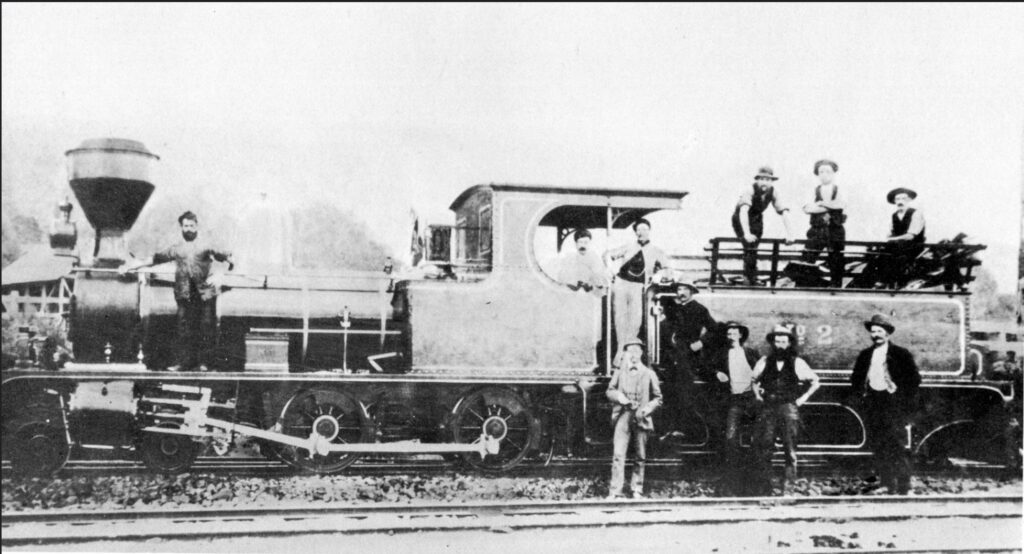

The biggest challenge faced by the new company was transporting equipment and machinery to Guildford and beyond. The original railway line between Emu Bay and Waratah was a relatively light construction, limiting the engine’s ability to work the line. Consequently, the three locomotives leased from the EBMBR Co. struggled to carry the equipment required to keep the construction progressing efficiently.

By the end of 1897, earthworks for nine miles of the new line were completed. The first major camp was located on the Hellyer River, which contained campsites for the workers, a store and stables for the 40 horses. A sawmill was established at Guildford Junction to cut the sleepers for the railway.

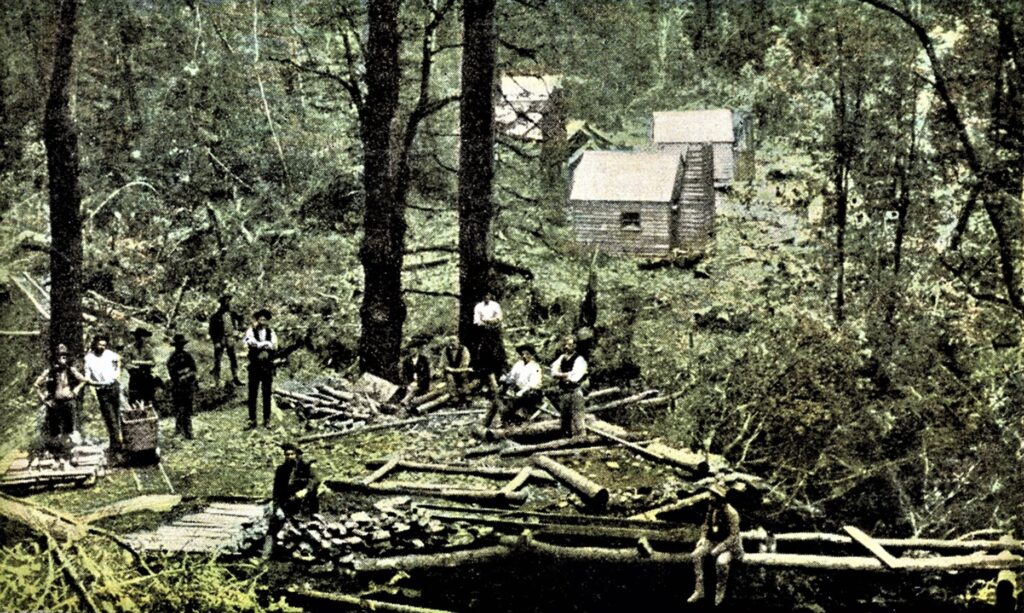

In February 1898, a second sawmill was operating at Guildford to cut the sleepers. James Stirling was appointed Engineer-in-Charge and was responsible for supervising the survey and construction works. Six teams of surveyors surveyed the route. Five hundred men were employed in building the railway line. The 70-man clearing gang were at the 12-Mile, where they struggled to get through the dense rainforest. The earthworks gang wasn’t far behind, reaching the 11-Mile, and the concrete workers were building a bridge at Hatfield, the last big bridge for several miles.

While progress was satisfactory during the drier summer months, it was a different story during the remainder of the year. Stirling reported it rained 90 per cent of the time, and the “wet boisterous weather” led to poor working conditions and soaring labour costs. By August 1898, 1,000 men – equal to the population of Burnie – were employed on the line, most sourced from Melbourne. Store camps were at Hatfield, Que, Boco and the Pieman River crossing. Despite the poor weather, all the clearing works were completed to Rosebery by the end of the year.

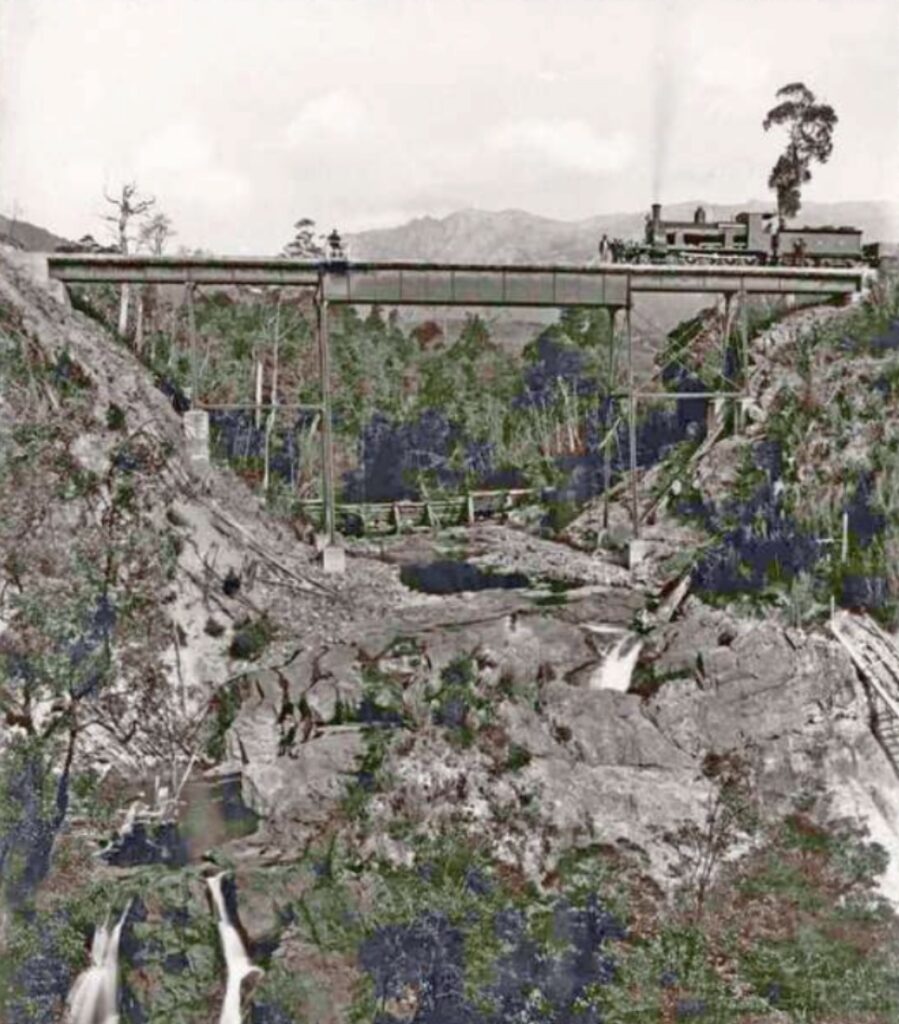

After leaving Guildford, the line went through open and relatively flat country for 11 miles. It then descended into the Que Valley, following the western banks of the Que River for six miles through dense horizontal scrub and rainforest before crossing the river over a substantial wooden trestle bridge 280 feet long. Once out of the valley, the line went through the button grass plains surrounding Bulgobac before entering Boco Valley and descending to the Pieman River for seven miles. The Pieman section was the most difficult to construct. Many sharp curves were used to keep the gradient at a constant 1:40 through the rugged sections.

The official opening for traffic to the Pieman section occurred on 7 February 1899. The Pieman bridge was built of steel trusses on concrete foundations over three spans – one 150 feet crossing the river and two shorter 25 feet. The lattice girder bridge was manufactured in England by Andrew Handyside and Company at the Brittania Foundry Derby.

During the construction to the Pieman, any interest in building a branch line to Queenstown disappeared. Works in Macquarie Harbour to deepen the Hell’s Gate sand bar allowed larger ships to enter and made Strachan a much better option for the Mount Lyell field.

On the section between Rosebery and Zeehan, the line had to traverse Stitt and Ring Rivers in deep gorges. By the end of April 1900, the railway line was completed to the Ring River, and the earthworks were practically finished to Zeehan. Track laying couldn’t continue until the Ring River bridge was built. However, because the steel girders for the bridge could not be obtained in Australia, they had to be ordered from an iron foundry in England, further delaying work.

A significant problem for the works south of Rosebery was the inability to transport men and materials along the formation before laying rails. Pack horses were unsuitable as they loosened the newly made fills. A temporary two-foot gauge wooden horse tramway along the formation sped up deliveries and movement.

The Ring River bridge was a major undertaking. It was 285 feet long, with nine spans of 30 feet and one of 15 feet. The steel was procured from Salisbury’s Foundry in Launceston and railed to the site in pieces.

At the 44-Mile mark, just seven miles from Zeehan, the engineers decided to build a quarter-mile tunnel through the large Serpentine Hill. Work on both sides of this tunnel commenced in March 1899. Work on the Rosebery end progressed faster than the Zeehan side. A work gang construction camp called Hill End was established near the tunnel on the Zeehan side. It was abandoned after the tunnel was built.

On 7 April 1900, the Argent Tunnel at Hill End was holed through, and the breaking down and cementing of the tunnel commenced. The Rosebery side had been broken down for some distance and lined with cement. A water race from the Ring River provided water to drive the four Pelton wheels and to power electric lights, concrete mixers and a blower for fresh air inside the tunnel. The 400-metre tunnel was finished, and the first train went through in November 1900.

Hill End was established as a base for the tunnel construction workforce, supporting at least 80 workers. As well as hosting a post office, there were reports of sly grog shops, two-up schools and “disorderly houses”. Being isolated, the men entertained themselves with gambling, and police watched “the schools” closely to curtail their activities.

The opening and operating the line

By November 1900, following the completion of the Argent Tunnel, it was just a matter of connecting the Dundas railway at the new Rayna Junction and upgrading the light Dundas line rails from there to Zeehan yard. A few days before the official opening, a special train ran from Burnie to Zeehan carrying Stirling and the Tasmanian Government Railways’ Engineer-in-Chief, John McCormick, who inspected the line and all the bridges.

The line was officially opened on 21 December 1900, after it took three years to build the 48-mile extension, costing a total of £494,535. It now meant Burnie could be reached from the west coast in hours without relying on an arduous west coast sea voyage.

However, what was most troubling was the financial losses incurred in running the line in its first four years. The fall in metal prices meant the mining companies struggled to afford to mine, smelt and export their large reserves of second-rate ores, the first-class ores already mined out.

At the 5th General Meeting of the EBR Co. in March 1902, the chairman didn’t hold back in outlining the financial situation:

“It is not pleasant, gentlemen, to have to lay before you such results from the year’s workings. It is no use mincing matters, they are unsatisfactory”.

Things began to improve in 1905 when metal prices improved, and the company recorded a small profit. That performance was repeated over the next six years until 1912 when the mining industry boomed with a dramatic increase in ore transported over the railway line. Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War I led to the loss of workers and the closure of smelters, affecting the profitability of EBR Co.

The fortunes of EBR Co. waxed and waned over the next 50 years due to depressions and wars interspersed with new mines and booming metal prices.

Concluding remarks

For the VDL Co., constructing the 48 mile railway to Zeehan was a significant boon for its land business. The port at Burnie was the premier facility on the north-west coast, and as the town boomed with new companies and industries, so too did the land prices.

Even though VDL Co. failed to make any fortune on their original intentions to breed Merino sheep and sell wool to the textile factories in England, the construction of two railways to access and take advantage of mining on the west coast, in no doubt helped generate revenues they struggled to make from the traditional use of the land holdings. The development of a major port also allowed them to profit from land sales as part of the growth of a significant town.

Wonderful read. I am a west coaster and only now have time to delve into our history outside the west coast.

It puts into perspective the tenacity of pioneers who built and opened up the west and north-west of Tasmania.

As usual, an amazingly well documented read with some magnificent photos.

How they built some of those bridges in those days with limited tools like we have today is simply amazing. Well done Robert!

Thank you for the story of the EBR. Having worked there in three diiferent roles. I found it very interesting.

This is such a great story about the beginning of rail transport on the West Coast, and the mammoth effort those workers did to forge through such dense vegetation and rough terrain. We owe them a lot to have built those lines with very little mechanic assistance. It’s certainly a part of our history that should not be forgotten.

Well done once again Robert.