“Soon the haunting atmosphere of these forgotten farms will be a thing of the past and stately forests will reclothe these fertile acres”. Cath Lott

Introduction

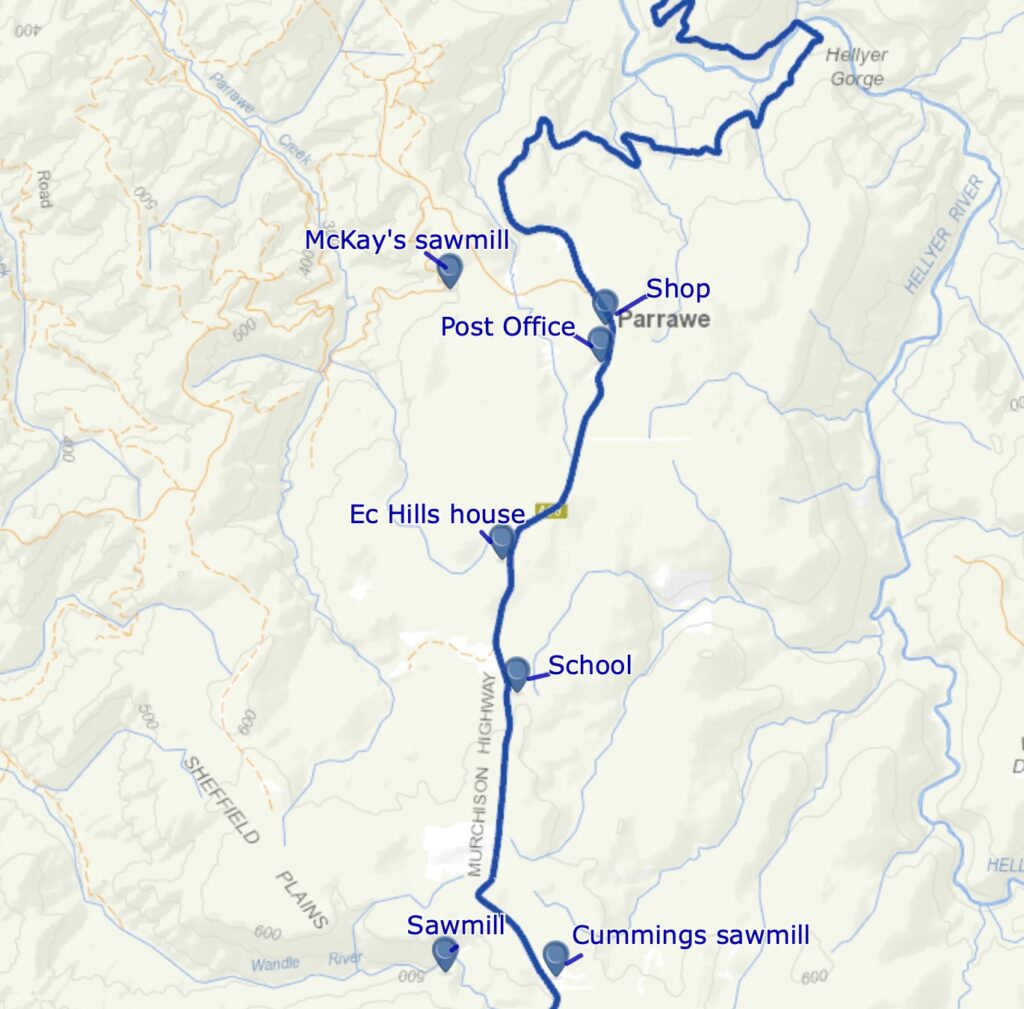

Parrawe is located on the basaltic plateau immediately west of Surrey Hills, north of the Wandle River, and south of the Hellyer Gorge. This tongue of land ranges from 500 metres to 640 metres above sea level. It has an inland cool temperate climate with relatively high annual rainfall, similar to the surrounding Surrey Hills estate.

Myrtle rainforest covered the area until European settlement in the early part of the last century, and the first settlers cleared most of the plateau. There were two plains free of myrtle forest containing native grasses at the southern end of Parrawe called Sheffield and Bells Plains. Early settlers from the Yolla district cleared a lot of the plateau. Today, pine and eucalypt plantations cover most of the former cleared areas. The remaining cleared areas support scattered native shrubs, particularly pepper bush, with a grassy or mossy understorey.

Very little native remnant native vegetation remains except in the Sheffield Plains area and on the slopes below the plateau. Dairy farming and cropping prospered for a short period. Up to ten sawmills utilised the hardwood, myrtle and sassafras resources to supply local, interstate and overseas markets. This isolated farming and sawmilling community, not recognised until 1935, when it was officially listed as a “town”, etched out a living from the tail end of the depression for about 30 years before a combination of poor commodity prices, rabbits and the end of tariffs on certain timber products, signalled the end of this once small, but vibrant community in the late 1950s.

Parrawe’s climate was generally favourable for farming, particularly during summer. While it experiences cold, wet winters with scattered snowfalls on the plains, it gets a warm but relatively wet summer. This is what attracted the sons of the pioneers who cleared the Elliott and Yolla districts earlier.

Little is documented of the Aboriginal history of this area over the long period before the European settlement of Tasmania. It is known that the local people moved through on a seasonal basis, utilising the available resources with extensive chert (used for aboriginal stone tools) and chert quarries scattered through the area, particularly around southern Parrawe. Indigenous people appear to have continued to use the site up until and after the arrival of Europeans in the late 1820s. Henry Hellyer documented the presence of Aboriginal people, including huts, some with drawings, in the Surrey Hills-Hampshire Hills area as part of his explorations.

Archaeological work in the early 1990s found brecciated chert on open sites at Parrawe and a nearby stone tool chert quarry. Further detailed investigation showed that the quarry was a source used prehistorically by Aboriginal Tasmanians. Aboriginal quarrying activities extended west across Parrawe Creek, where undisturbed deposits and brecciated chert outcrops are known. Archaeologists estimate from this work that the total area of Aboriginal quarrying was approximately 125,000 square metres. Carbon dating analysis dates a hearth at the quarry between 3,490 and 2,770 before present.

Although it is officially known as Parrawe, which is Aboriginal for abstain, the locals spelt it Parrawee, and newspaper reports about the settlement always referred to the latter spelling.

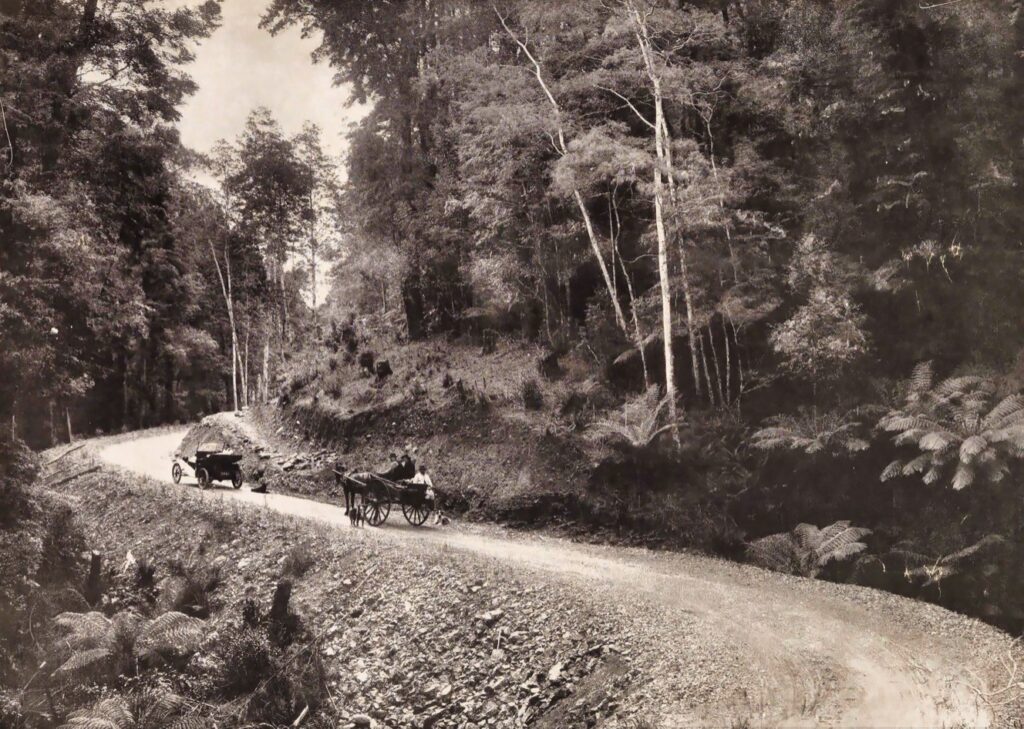

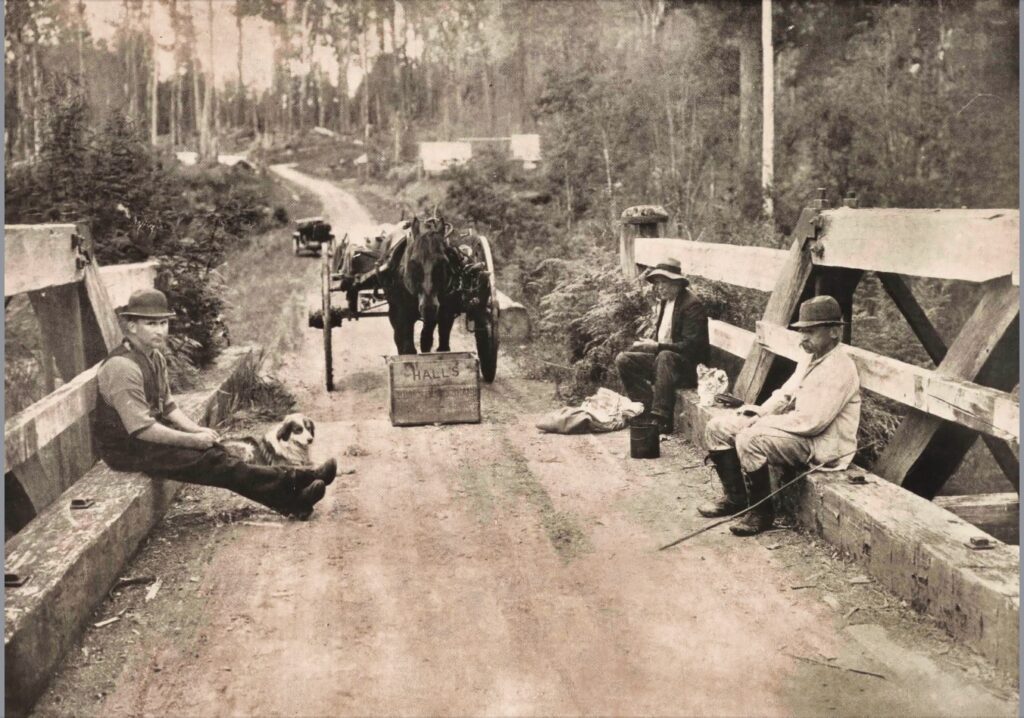

Access to Parrawe

For many years, there was debate about the most suitable road location from Waratah to link the town to the north-west coast. One route was from Burnie through land owned by the Van Diemen’s Land Company. The other was from Wynyard, to Yolla and Henrietta, through the Hellyer Gorge, mainly over Crown land. In late 1886, the Tasmanian Parliament “voted” £5,000 towards the grubbing and removing timber for a road on the latter route. The government only spent money on work at both ends of the road. The Waratah residents didn’t care which route a road to the coast took as long as they had access to the coast. The fact that Waratah generated substantial revenues for the government through mining royalties at the Mount Bischoff mines, however, didn’t hasten the construction of a road.

In July 1904, the Public Works Department (PWD) called tenders to form a road from Henrietta south through the Hellyer Gorge to Waratah. The existing road was the chief artery for the Mount Hicks, Yolla and Henrietta districts, some of Tasmania’s best-producing and most closely settled dairying country. Thomas Butler of Sheffield won the contract for £150, which didn’t amount to much for providing an all-weather road between Waratah and the coast.

A large public meeting was held at Waratah in September 1910 to raise the issue of road access to the coast for the residents of Waratah. Another prominent public meeting was held a year later, highlighting that the Waratah residents needed an access road to the coast, and the Parrawe selectors and prospective residents needed an inlet to Waratah to get their stores and supplies to market. Some selectors argued that it would be cheaper to focus on putting in a metalled road from Parrawe south to the junction of the Burnie Road near Waratah to access the Emu Bay Railway than to try and build a metalled road to the coast. The Parrawe settlers presented a petition to the Waratah Council to that effect.

In 1911, Parliament voted to spend £2,000 on the road “Waratah to Wynyard Parrawe settlement”, the intention initially believed to give an “outlet for the Parrawe settlers towards Wynyard. However, after representation from the local member, they realised that contractors had already carried out work to Parrawe from the coast. They directed the money be spent on culverts, forming works, and metalling the road between Parrawe and Waratah.

In 1914, after an inspection by the Minister of Lands, a further £15,000 was allocated to complete the road to Waratah for light traffic. But even in 1918, the road wasn’t fully completed, despite the recognition that “Crown lands of splendid quality in the vicinity of Parrawe which could soon be taken up if the selectors could get in and out at any time of the year”. A fully functional road had been promised year after year for over 30 years, with only £37,700 spent building a rudimentary track since 1877. Guaranteed access to Waratah was only via a privately owned railway, which, because of its monopolistic grip, was accused of charging heavy freight charges, making life in Waratah very expensive.

A Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works tabled its report about the Waratah-Wynyard Road in September 1915. The report recommended the completion of the road at an estimated cost of £12,000. The Committee visited the road and noted that “about seven miles of almost impassable road is encountered” at Parrawe.

The government allocated funds to the PWD to complete the road by the end of the 1920-21 summer period. However, by April 1921, the Waratah Councillors were anxious that there was no work to done to complete the road. They were concerned that if the section of road on the southern side of the Hellyer Gorge was not metalled, it would be impassable during winter.

The road was finally completed between the coast and Waratah in late 1921 using bullocks, pick and shovel and was known as the Waratah Highway. Workers laid down blue metal to provide safe and continuous road use all year round.

Repair work on the road was carried out in 1924 between Waratah and the Wandle River to assist with access for locals and tourists over the summer. The closure of the Mount Bischoff tin mine in the late 1920s created many unemployed workers at Waratah. Many workers secured jobs maintaining the Waratah Highway.

In the early 1930s, seven men were employed to maintain the road. By 1936, the department reduced the gang to overseer Teddy Belbin and four workers – Ted Smith, Bill Armstrong, Reg Diprose and Jim Saltmarsh – to maintain the whole Waratah Highway even though motor traffic had increased by 80 per cent.

Belbin pointed out, “the principal item of cost on the road is pick, shovel and wheelbarrow”. He used a truck for binding via limestone dressing for only five days a year.

By 1943, the maintenance gang was one man in the Parrawe section. George Kingshott was the Parrawe patrolman responsible for looking after the section from the northern side of the gorge south to the Wandle River. The department decided to build a cottage for Kingshott to house himself and his family in 1943. Initially, the plan was to locate the cottage on a small section of Crown Land known as the Parrawe Town Reserve. However, it was unsuitable because it was three miles from the school, was far from the nearest neighbour, and had no access to permanent water. Instead, they chose a two-chain square site opposite the school site on Richard Smith’s property for £3.

The government built the first road link connecting the north-west coast directly to the west coast and opened it in December 1963. It was a much higher standard road, widened and bituminised over its length. Until 1973, the main road or highway was known as the Waratah Highway. After that, it was renamed the Murchison Highway.

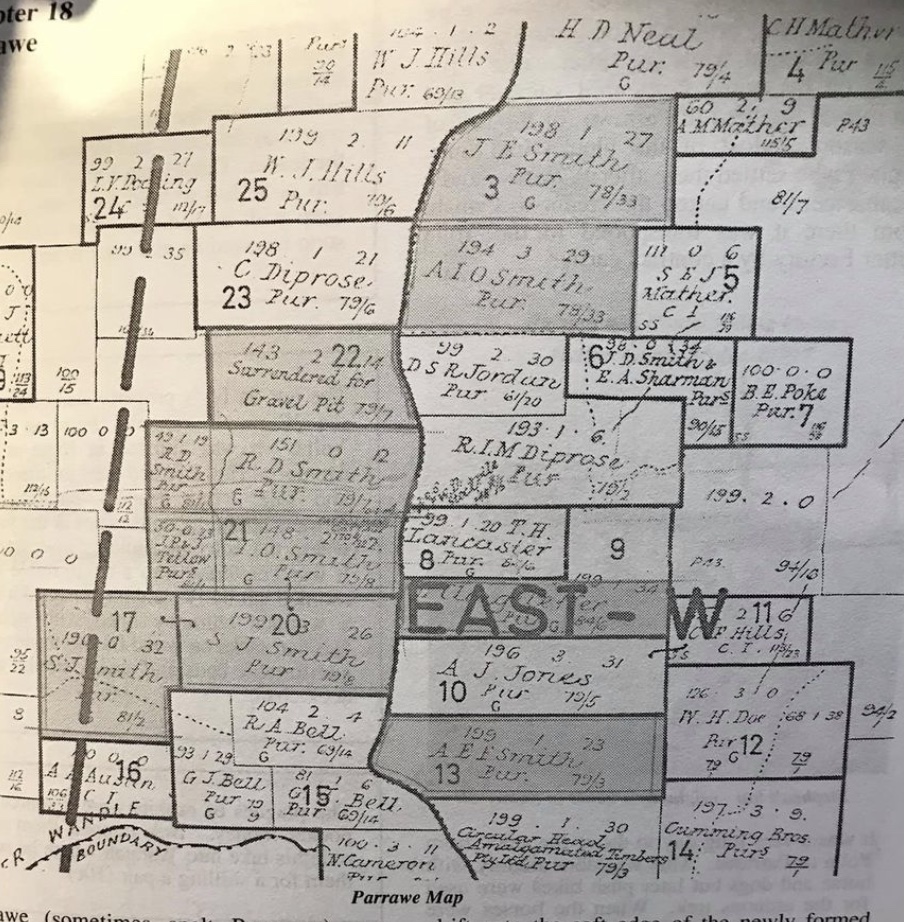

Selection of farming blocks

It has been claimed in some books covering the history of Parrawe that it was a soldier settlement scheme. That is not correct. The initial selection of blocks for farming occurred between 1906 and 1910 when 10,000 acres, divided into 100 to 200-acre blocks, were surveyed for purchase. It followed the Commissioner of Crown Lands opening a large area of Crown Land in the north-west in early 1906. In 1908, the Government Chief Surveyor reported that no land was sold in the Parish of Parrawe:

“…but now that the restriction as to area has been removed, I am credibly informed that the greater portion of this very rich land will be speedily selected”.

Most of the selectors worked at the Mount Bischoff tin mine for part of the year to earn enough money to carry out the improvements on their selections during the summer. With just an axe, a saw and the use of fire, they cleared and scrubbed the land free of rainforest and eucalypts.

Tragedy struck in May 1909 when four young men from Yolla went to Parrawe to carry out manual clearing and scrubbing on some land they had taken up. Hector Crisp, Herb Neil, Len and Edgar Smith were working together. Hector was falling a tree, but the butt hit and killed him. The others made a stretcher and carried Crisp 12 miles through the bush. Too exhausted, they left the body and walked the remaining miles to Yolla, arriving in town about eight o’clock that night. They immediately arranged a car to retrieve the body. Hector was 18 years old.

By 1915, farmers had selected 5,000 to 6,000 acres, and a considerable amount of rough clearing and fencing had occurred. This work was estimated to cost £2-10 per acre. However, few settlers were residing at Parrawe, and no farming had started.

One of the notable first settlers was the Smith brothers. Patriarch Daniel Smith was an early farmer in the Barrington area before moving to Yolla in the early 1900s. He had fifteen children, including eight sons, who were all involved in farming. In 1905, they looked elsewhere for other areas to develop as cattle runs after all their land in Yolla was cleared, scrubbed and sown with pasture. They decided to try and clear blocks at Parrawe. Seven of the eight sons took up land in Parrawe. The most notable was Stephen John, the third son. Stephen saw service in WWI, where he was wounded in Flanders. After his return, he was a Councillor for the Waratah Municipality for over 17 years.

Despite his disabilities from the war, Smith was milking 45 pure-bred Jersey heifers in 1926 with an “up-to-date milking machine driven by an oil engine”. He was described as a “progressive agriculturalist” who also ran a piggery.

There is a long piece of remnant dry stone wall that exists today at north Parrawe, and by coincidence, a sawmill nearby opened in the 1920s run by Charles Dunham, who was also the first stone supplier in the region. Some claim that master stone wall builder William Smith erected the stone wall with the stones supplied by Dunham sometime between WWI and WWII. However, I have also read that Charles Mather built the wall.

The most well-known Parrawe settler was Colonel Sir George Bell, born in Sale, Victoria, in 1872, with a distinguished military and Parliamentary career. He fought in the Boer War, enlisting as a private in the 1st Victorian Mounted Infantry Company. He returned to Australia in December 1900, but after calls for reinforcement from the British the following February, he re-enlisted as a lieutenant in the 5th Victorian (Mounted Rifles) Contingent. He was severely wounded, mentioned twice in dispatches and awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1902.

In 1905, he resigned his commission in the Light Horse Regiment and became an honorary captain in the Commonwealth Military Forces. During this time, Colonel Bell took up land at Henrietta and Parrawe and retained ownership of his blocks until his death. He made a name for himself as a successful “fattener of stock”. However, two of his cattle-grazing properties at Henrietta, including his home and stock, were destroyed in “one great sea of flames”when a bushfire roared through the area on 31 January 1906.

In 1914, Colonel Bell enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Australian Light Horse Regiment, seeing service at Gallipoli, Egypt, Sinai and Palestine. During the war, he was promoted to lieutenant, captain, major and lieutenant colonel to lead the Regiment. He earned the reputation as “one of the most aggressive and astute leaders produced by the light horse”. Colonel Bell took part in the capture of Jerusalem, where he was awarded a Companion in the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George in 1918.

After WWI, he served in the Federal Parliament, narrowly winning the north-west Tasmanian seat of Darwin against Labor candidate and future Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. He was known as “one of the most able debaters in the House” and strongly supported mining and sawmilling.

He was Speaker of the House for six years and was a highly respected politician, earning significant praise from Prime Minister John Curtin after his passing. He received his knighthood in 1941, shortly before he died in 1944.

The pioneer farmers cleared and scrubbed their blocks during winter and burnt them the following summer. Blocks were heavily forested with large trees interspersed with smaller species and man ferns. Fires burnt the smaller species completely, but the big myrtle logs remained, although blackened by the fires. Farmers split many logs into posts, palings and firewood, and loads were carted to APPM Burnie, which used them to fuel the boilers.

One advantage of these blocks was that they were situated in a high rainfall area on beautiful basalt soil. After the initial clearing work and burning, they sowed English grasses into the ash following the fires. In addition, there were no rabbits. Improved pasture growth was prolific. Elsie Smith recalled being overwhelmed on leaving the car by the scent of wild white clover. Three or four permanent settlers established the first dairy farms in the area. A spring dray carted their cream to Oonah, which was picked up by the carter and delivered to the Yolla Butter factory. They also grew potatoes.

There were high aspirations. While there was still much development work, the selectors visualised that Parrawe would have the same appearance as the older settled districts closer to the coast they came from, such as Yolla and Henrietta.

There was a large bushfire in the area in February 1915 when fallen trees blocked the Waratah Highway. The fire started at the 26 Mile on the railway line and burnt a large area, including Oonah and Moore’s Plains. There were other fires at Rocky Cape and Flowerdale, making it one of the worst fire years in north-west Tasmania’s history after the 1934 fires.

By the early to mid-1920s, the first settlers had obtained ownership under a Purchase Grant of their selected lands after completing payments of the instalments on their Crown Purchase Agreement. Selby Diprose, Alf Jones, Syd Jordan, Keith Diprose, James (and Neil) Cameron, Dare Diprose, Herb Neal, Thomas Lancaster and Edward Pearce were the early selectors of the area.

Yolla farmer Ivy Smith milked on his home farm until early December and then moved the herd to Parrawe for the rest of the season when rainfall promoted late summer and autumn feed. Fred Saxon did likewise.

A few fires again hit Parrawe in early 1926. The most notable was a fire in February that burnt Martin Hogan’s hut during his absence. Luckily, the pastures were green, and there was minimal damage.

A telephone line was extended to the district, which allowed residents to talk to people in Burnie.

In 1927, there were glowing reports about the potential of the land at Parrawe. There was a road through the district, and most available land had been cleared and sown with pastures. The cattle “were round and fat…and a better country for dairying cannot be obtained for the state”. Absentee farmers owned most of the land and ran stock on their holdings during the summer.

Stephen Smith’s 600-acre dairy farm was all practically under grass, supporting over 100 Jersey and Jersey-Friesian cows. Hand milking was too slow, so he installed up-to-date milking machines.

This situation, however, changed the following decade. Another round of selections followed WWI for returned soldiers on generous loans. The federal government created the Soldier Land Settlement Scheme to settle returned soldiers on the land after World War I. After Parliament introduced legislation in 1916, properties were purchased around the state, including Parrawe. Many settlers submitted applications under this scheme in the early 1920s in Parrawe. They included applications from Jim Huett, Lucy Docking, Steve Mather, Bill Hanson, Cyril Hills and George Radford.

The 1934 bushfires across the whole north-west and west coast caused havoc. Parrawe didn’t escape the carnage. The homes of Thomas Lancaster and Ivan Smith were threatened and caught alight, but firefighters eventually saved them.

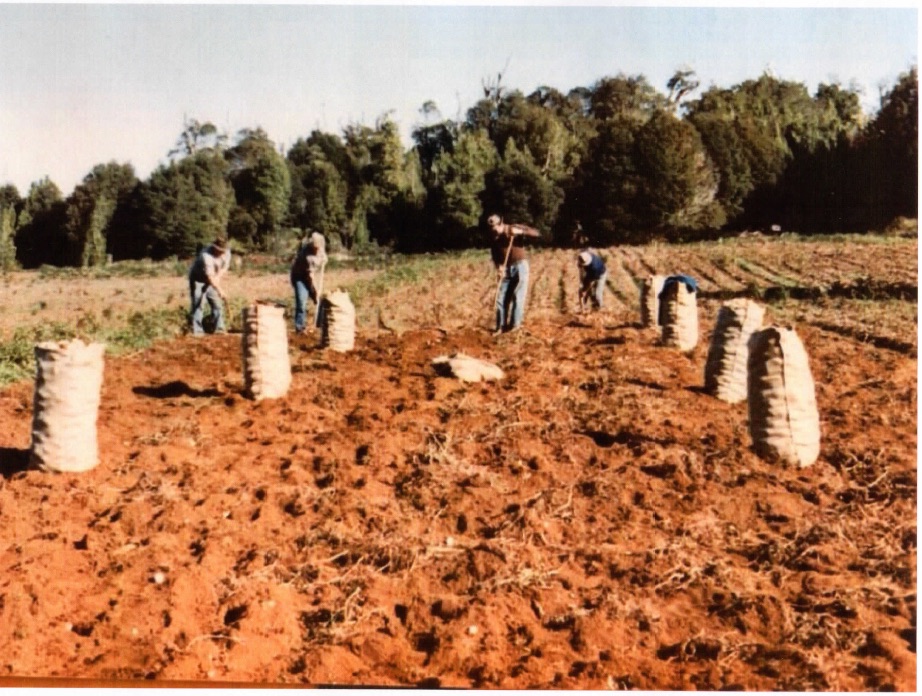

In 1939, there were 442 head of cattle and calves, 15 pigs and 177 milking cows on the Parrawe farms. Farmers produced 1,324 lbs of farm butter that year, 150 bushels of oats, 47 tons of potatoes, 16 tons of hay and 10 tons of straw. Potato production increased markedly after WWII, particularly the Brownells variety. One of the features of the Parrawe district was that it was a desirable location for growing disease-free potatoes, with a massive demand for seed potatoes from the area.

In 1943, farmers in the district made an urgent plea via the council for galvanised wire netting, barbed wire and corrugated iron. If a quantity of those materials were not released, the farmers would be unable to carry on. Waratah Council decided to write to the Director of War Organisation of Industry.

In 1945, about 20 occupied blocks were occupied, with about a dozen residing on their holdings. And a lot of areas had been sown to potatoes.

A request was made directly to the Premier in June 1954 to connect the six residences and five sawmills to electricity because a lack of power deterred people from settling there.

A post office was operating in 1927, soon after the road to the coast was completed. It was located on Pearce’s block, run by George Radford and his wife as postmistress. Residents relied on a tri-weekly mail service, but with the opening of the post office and the road, they enjoyed a daily mail service. The Mather family took over running the post office in 1943. Trevor and Patricia Wing ran it. The Listons ran the post office in 1951.

The Jozic family ran the Parrawe shop in the 1970s. They built the dam to run a waterwheel to provide power for their business.

Sawmilling

“New mills arise like mushrooms near and far, from Parrawe to far-farmed Waratah; The ‘horse pugs’ bellow on the sneaking tracks, the sturdy bushmen wield the saw and axe. The ‘headers-in’ are rushing ‘sassy’ through, the ‘pullers-out’ all show what they can do; the dockermen are working swift and well, all goes merry as a marriage bell.” AJW.

As well as farming, the residents of Parrawe were involved in sawmilling. The sawmilling industry at Parrawe was the mainstay of the district and employed many men. Late in the nineteenth century, Tasmanian sawmillers had many problems, mainly accessing resources under a secure system to justify expending capital. The Crown Lands Act was amended in 1895 to issue timber licences, giving the licensee the right to timber over a specified area. It initially started over 500 acres for five years. They became known as “exclusive leases”. However, sawmillers saw this system as inadequate for their needs, and the government made a further amendment to increase the permit area to 5,000 acres for 21 years at a set royalty rate for hardwood, pine and blackwood. While this form of security encouraged investment in sawmilling and tramways, there was concern about the level of cut and matching it with the growth of the forest.

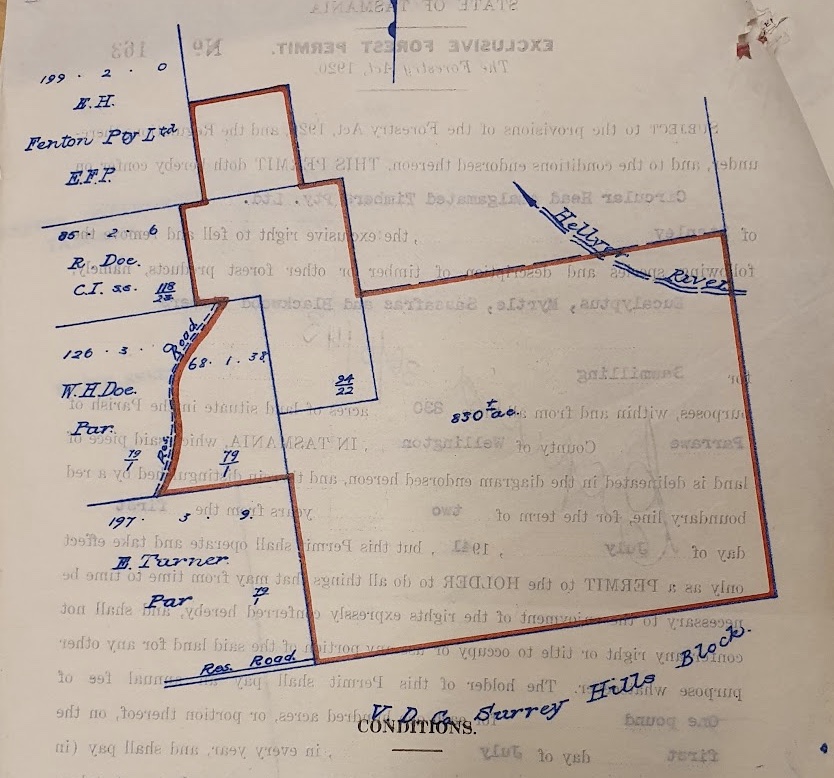

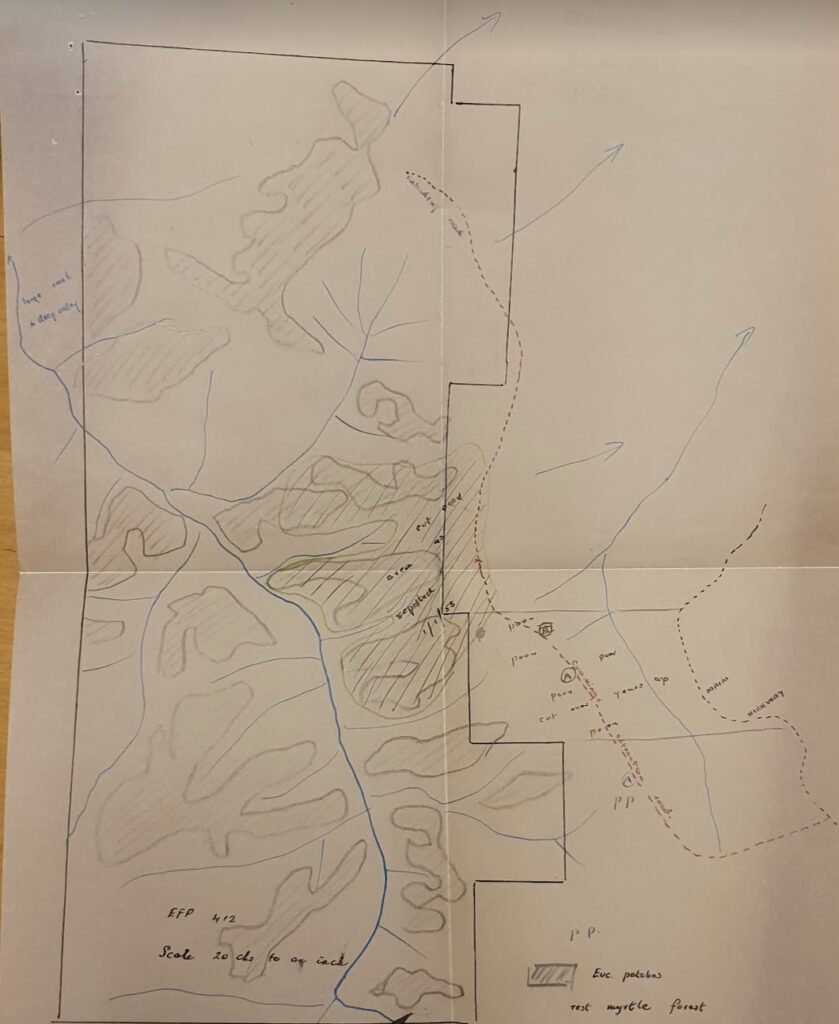

After the government established the Forest Commission under the Forestry Act 1920, they introduced an Exclusive Forest Permit (EFP) system to ensure areas were cut over properly for 15 years. Annual licences gradually replaced the permits.

While the forests around Parrawe carried eucalypt, myrtle and celery pine stands, they were one of the few areas around the state with sassafras in sufficient quantities to work commercially. Sassafras was sought mainly for the wooden peg market.

The first sawmill to operate at Parrawe was run by the Darwin Timber Company at the Wandle River, about 10 miles south of Waratah. It mainly supplied timber for the Mount Bischoff mine. Arthur Crisp was the manager of the mill. One of the company’s directors was George Causby, a local timber merchant. They also ran sawmills at Hampshire and Mengha.

The Parrawe mill began operating in 1923, and because the sawn timber was sent to the Emu Bay Railway eight miles away, there were always complaints about the damage to the new road. In July 1925, the Waratah Council were concerned about the damage to the Waratah Highway by trucks carting from the sawmill, and they charged the sawmill a road toll. In October 1925, the Darwin Timber Company reported it was in voluntary liquidation, and soon after, the Mengha sawmill was suspiciously destroyed by fire in 1925.

John Hanson ran a small sawmill near the Post Office from 1926, cutting 9,000-10,000 super feet per week of sassafras and myrtle mainly for the Cumming Bros timber yard in South Burnie.

In 1931, when Eric (Ec) Hills and his brother Frank first went to Parrawe, they said no sawmills were operating. However, in November 1932, there were reports that four sawmillers erected small sawmills within three miles of each other on the Waratah Highway between Wandle River and Parrawe. They were William Etchell, who operated several sawmills in the north-west; Harry Hanson, who ran one near the post office; Jack Bowie and George Bawer; and Len Moles, with his large mill closest to the Wandle River, called “Snake Gully”. They all worked at full capacity, milling hardwood, myrtle and sassafras for the mainland markets.

They were not large mills with the necessary equipment to saw sassafras and myrtle. Hanson’s mill was in a central position with timber stands for several years around the mill. The manager was Mr T. Harman. It cut 9,000 to 10,000 super feet weekly and sent the sawn products to Cumming Bros’ yard in South Burnie. Haulage was by horses and bullocks on tracks to the metal roads, where they were loaded onto trucks and taken to the mill.

In March 1934, the Bowie and Bawer sawmill was burnt out, including the loss of their stables and three huts as part of the destructive fires in the north-west that summer.

In December 1934, E. H. Fenton’s sawmill was erected 12 miles south of Waratah near the Wandle River and received a 1,500-acre Exclusive Forest Permit (EFP). The mill was known as “Bongoola”. However, they found that only 900 acres were accessible, the balance being across the “tremendous gorge in the Hellyer River”. The Forestry Commission advised Fenton to select the balance of 600 acres somewhere in the vicinity. They made no further application until May 1938, when they eventually put in an application for 2,000 acres beyond the Wandle River. Clyde Jessop had a licence over some of that area, who set up a spot mill on the Wandle River in 1936.

Unfortunately, in May 1935, the Fenton sawmill was destroyed by fire soon after starting operations. It was initially worked on contract by William Bugg. Mr Lorkin rebuilt the mill later that year, and it began working again in September, employing 12-14 men with twin saws and a new breast bench.

Ken Alexander recalls starting as a mill junior at the Fenton’s mill in 1937. He worked there until he fell and damaged his elbow the following year. His first job was to wheel out sawdust bins, which ran on wooden rails to the sawdust heaps over the side of the hill. The bins had loose sides, which could be removed to release the sawdust. Logs were brought to the sawmill from the nearby EFP on a wooden tramline pulled by draught horses.

In the 1950s, Fenton replaced the tramline with a board road comprising 3 x 9 x 2-inch boards connected by sleepers every six feet. The first truck to seen in the area, a snub-nosed Bedford, carted the timber to the mill via the board road. The truck delivered logs from the bush all day, and then in the late afternoon, it was loaded with sawn timber to be taken to the Burnie wharf.

Sawmills cut sassafras at 9, 12, 18, 24 and 27-inch lengths. The 9 and 12-inch lengths were put into potato bags, and the rest were tied into bundles. The 27-inch maximum length allowed the timber to be fitted to lathes to make cotton reels, bobbins and clothes pegs. The myrtle was sent to Melbourne to make lady’s shoe heels, and wide boards were cut for coffins.

Jessop’s mill was powered by water from the Wandle River, but after a few months, it proved a failure. He removed the sawmill to land owned by Bowie, and even though his mill was not classified as a Crown mill, the Forestry Commission gave him licences to cut sassafras and myrtle on Crown land adjoining the private property. Cummings decided to provide a boiler and sawmilling plant to Jessop as part of boosting their sassafras strategy and gaining an additional source of that timber. Cummings tried to obtain a licence on Crown land for Jessop, but Fenton’s opposed this and tried to apply for their 600-acre area in the same area.

Unfortunately, several events didn’t go Jessop’s way. The first was when one of his employees was critically injured in an accident at the mill. The second was a fire that burnt and destroyed the cottage at the mill in December 1938.

In August 1937, a new mill for Mole’s (Mill No. 2, locally known as “South of the Border”) was established on Surrey Hills estate near the Wandle River to cut sassafras. They also took many logs from Surrey Hills to their other Parrawe mill. A couple of months later, there was a serious accident at the mill when an employee tried to take a splinter from the circular saw and had his left hand drawn in, losing two middle fingers at the second joint and his first and little finger badly injured.

Towards the end of 1937, Hugh Fenton applied for and was granted a licence to cut sassafras on Crown land near Saxon’s property at the northern end of Parrawe on the western side of the highway and again in February 1938. The department was reluctant to issue licences to extract just a single species as it decreased the value of the area for sawmilling purposes by other applicants in the future. They located their sawmill on the Waratah Road frontage in the old Parrawe township reserve and built several “comfortable” cottages for the families of some of the workers. Fenton’s also had a hand-pump petrol bowser selling fuel to the public for a handy profit.

Fenton was adept at getting involved in a few local issues associated with the competitive sawmilling interests in the area. In early 1939, he was interested in an EFP issued to Mr Jaeger to remove blackwood and celery top pine to the north-east portion of his EFP. They stated they were “vitally interested in this area, and that our whole future as sawmillers is tied to this matter”. He also complained to the Forestry Commission that Cummings was not harvesting sassafras south of Lynch’s Creek.

In 1939, Fenton, Dunkley Bros at Stanley and the Circular Head Timber and Kiln Seasoning Company combined to form Circular Head Amalgamated Timbers Pty Ltd (CHAT). In July 1941, CHAT was granted an EFP over 830 acres of land above the Hellyer River at the southern end of Parrawe adjoining Surrey Hills and another EFP in a nearby area. They abandoned their EFP in the early 1950s.

Len Moles and his family moved from Parrawe to Burnie in November 1942. He was still operating one of his mills in 1944 when the court fined him for not following regulations regarding first aid equipment and providing information for employees at the mill. The Union took the action in the local court in Burnie.

Cumming Bros were issued with three EFPs around Parrawe covering over 3,000 acres in 1947. In March 1948, a grader was sent to work on the road to their sawmill at the ex-CHAT site on the north side of North Goderich Road. Their mill began operations in 1950. It cut 15,000 super feet a week and had a stationary boiler, vertical breakdown saw and breast bench. They cut timber mainly for the interstate markets for turnery and furniture (80 per cent) and 20 per cent for local markets for framing and joinery. They employed 12 men.

In 1945, three sawmills were operating on the southern end of Parrawe. They cut predominantly myrtle logs and sent them to the plywood factory at Somerset. In August 1951, Cumming Bros purchased the Cole block and logged about 100,000 super feet of myrtle and sassafras, building a board road for £500.

Que River Sawmills (McKay and Lloyds), owned by Mr R. T. McKay in 1947, bought Docking’s block for £140 and logged it. In January (or February) 1949, they paid £300 to Alice Dunham, soon after her husband Charles died, and logged the property for their sawmill. It was on the old Parrawe town reserve. The sawmill site was two hectares adjoining the town reserve of 57 hectares. By 1970, the sawmill site, fronting the highway, was overgrown with ferns, and the sawmill lay in ruins surrounded by sawdust heaps. Karl Nagl applied to purchase the lands in 1970.

In 1954, five sawmills were operating at Parrawe. They included Que River Sawmills (McKay & Lloyd), located next door to Ec Hills and had a house for sawmill workers. They closed in about 1968.

In December 1961, Cumming Bros closed their mill, with 12 employees losing their jobs. In 1965, the Forestry Commission advised Cumming Bros that because their Somerset sawmill was being supplied by sawlogs from integrated operations by AFH under their General Forest Permit associated with the 1926 Concession at Parrawe, EFP’s 900, 940 and 955 would not be renewed after expiry on 30/6/65.

Schooling

One of the difficulties in settling at Parrawe with a young family was its remoteness and lack of facilities. As more land was cleared in the 1920s by the new settlers and some moved to the area to farm full time, a request was made to the Education Department to provide a sum of £25 to the owner of a motor car who drove between Waratah and Burnie daily to transport the three children of school age to the Upper Henrietta school. The Minister agreed to provide an allowance for families transporting their children to the school not exceeding sixpence per day for each child.

In October 1934, the residents at Parrawe petitioned the Education Department for a school, claiming there were 13 children of school age and several others approaching that age. The residents offered to provide a suitable building. A subsidised school was opened the next month, with eleven students attending under the tutelage of the competent and experienced Mrs M. E. Jessop, the inaugural teacher. It played an essential role in the development of the Parrawe district, as the main drawback in the past was that the settlers had no facilities to educate their children in the remote district.

In 1936, when the local Education Department Inspector, Mr Jones, visited the school, rain was falling and coming through the roof. He wrote to the Director of Education, pointing out the building was unsuitable for winter in such a cold climate. While he said it may pass as a temporary option in fine weather, they should condemn it for use in winter. The sky could be seen through the roof in at least a dozen places, and rain drips onto the desks. He even highlighted that “shovelfuls of snow had to be taken from the desks and floor before the room could be used for school”. He said that Ivor Smith offered two acres of land for a school site for free and that the disused school building at Lapoinya could be transported to the district.

However, Smith denied he made that offer when approached. If the land was required on his property, he offered to sell one acre in the north-east corner for £7. The department rejected this. Jones said, “there is a probability of having a new school shortly”.

In February 1937, at a meeting between the Parents and Friends Association, Captain Bell and Jones decided to obtain two acres of land across the road from the present site on Thomas Lancaster’s property for a permanent school location for £16.

In March 1937, the department nominated the Big Creek School buildings at Wynyard to be relocated to Parrawe rather than erect new structures from scratch. There was a 24-foot x 17-foot classroom with a sheltered porch, kitchen, bedroom and two out-offices.

Meanwhile, winter that year was freezing and wet in the original school building. In June, there were 23 frosts and on one day in July, there were two inches of snow. There was also an “epidemic of influenza” that month, and several children were very ill owing to the state of the “draughty” school building. September saw another epidemic, this time German measles. Hail fell through the roof in October, and the cold was intense. The school children were anxious for the promised comfort of the new school building. If those events were not enough, an outbreak of Infantile Paralysis in the state in mid-December abruptly closed the school two weeks early.

Alfred Whiley, known by his second christian name Vernon, offered to clear all timber and stones, fill in holes, level and plough and harrow the new school site for £20 in preparation for the arrival of the new buildings. Sure enough, in late 1937, a more substantial building (formerly the Big Creek school building from Wynyard) was translocated to the area as the official school building. The school building had one room and one teacher covering grades one to seven.

Once the buildings were established across the road, several maintenance jobs had to be done before school started in 1938. A contractor had to install hobs for a stove in the kitchen, brass taps to basins in the porch, replace fastenings on windows, paint the bedroom, fix architraves and skirting boards, erect a nameplate for the school at the entrance, remove rubbish, clean out buildings and complete gravelling of the main path.

The 1938 school year started tragically when nine-year-old Zoe Hills was taken ill with Infantile Paralysis and died within a few days. Keith Mather and Harry Moles also suffered from the disease, and both recovered after spending time in hospital.

Only a few years after his death, the school held a ceremony as a memorial in honour of Stephen Smith. The school proudly displayed an enlarged photo as a memorial to the much-loved pioneer of the Parrawe district. Smith worked tirelessly to improve the conditions of his fellow settlers in their remote location and strongly advocated for a school in the district during his 17 years on the Waratah Council.

Mrs Jessop successfully requested ornamental trees be planted at the school in 1938 to sit alongside the macrocarpa cypress pine planted at the front of the school and donated by Smith. Once again, it was a bitterly cold winter, accompanied by an epidemic of boils, which meant attendance at school was not so good.

In 1939, Edna Shipton replaced Jessop as the teacher. The number of school children increased to 25 students. She resigned to get married in January 1940 to James Johns, a teacher in Brisbane. While only there for 12 months, she was a very popular teacher.

Ruby Dunham started in 1940 as the new teacher. However, after the first term, she also resigned to get married. She returned to Guildford to marry Emu Bay Railway employee Charlie Wilson. Elaine Castle arrived in April, and Eva Whiley welcomed her with “beautiful fires burning in clean fireplaces”. Castle came from the Tewkesbury School and provided an extraordinary tirade over seven pages against Inspector Jones in the school record book. Her gripe was mainly about dealing with:

“…a family of filthy minded boys, who often did dirty actions in the playground and whose language was filthy”.

Castle felt she didn’t receive any support from Inspector Jones. She was embroiled in issues with him at Tewkesbury. She thought she may have evaded his influence by moving to Parrawe. Still, he was forced to move to another district after experiencing complaints from parents in Tewkesbury who supported Castle. She wrote her spiel at the end of the school year after she resigned and got a job in Victoria. While she said she liked Parrawe, we get a detailed account of living conditions in the school residence. She doesn’t hold back:

“…[the residence] is not yet civilised [but] I made the best of it. The miserable climate does not add to comfort. Drift snow gets in under the iron roof and leaks through the ceiling boards. I had to move my instruments hither and thither to avoid the drips when they came down in a dozen places. After a bad snow storm, the kitchen floor is always wet. The bedroom leaks in two places beside the drains which come under the window and by it. When the rain comes from the east it drains in under the kitchen door and sometimes forms quite a stream. I was warned not to put good lino or carpet on the floor and was glad I took the advice. I moved the big library cupboard into the kitchen and hung curtains from it to form a break wind. It added much to the comfort of the place. The fireplace is quite annoying too, being up in a corner in that position besides the fact that one has to bring the ironing into the school room to do, for there is no room in the kitchen fireplace to stand the irons when a bit of fire is there. It is dangerous too for fire often falls out. It is dangerous too for fire often falls out and it is necessary to keep one there during school hours if one has a musical instrument, for the dampness spoils the instrument’s action. Clothes which are hung up in the old rustic wardrobe become mouldy and in that way my raincoat was spoiled. It is really necessary for a fireplace in the bedroom…It is bad enough when one cannot enjoy company occasionally when there is none to enjoy…one needs a change from reading with one’s feet in the oven”.

Zetta McKerrow was the teacher in 1941 and concluded her duties “after a happy year”. The following year, Nancie Cure, from Waratah, arrived as the new teacher. Student numbers were high at around 27. However, she complained every time the community held a dance at the school. She raised issues such as pictures torn from the walls, charts pulled down and torn, walls scribbled on, and half the books stolen:

“In previous reports I noticed when some books are missing from the school and from my own experience, I should say that while ever the school is used as a dance hall books and records will be missing. It is very disheartening for one to have to make new charts and buy new textbooks every fortnight”.

Keith Martin was the teacher for six months in 1944. When he arrived, he wasn’t happy with the state of the school and residence, complaining of dirt on the floors and the rubbish that littered the home. He railed:

“The curtains to the windows were almost black while the windows were not fit to look through…The sinks and hand basins were black and by the look of them, they had not been cleaned for some time. The yard was littered with logs of wood, papers, big stones and bottles. The school gave no encouragement for a junior teacher, who was starting off solely in charge of the school”.

He got the children to clean the windows, wash basins, sweep the floors, clean the residence, and make the yard “respectable”. He wrote that the school looked in a “fit condition for one to teach”. The drains were blocked, which the council had failed to fix, so Martin and the students did the job themselves.

The medical examiner, Dr Cahill, visited the school and examined every child; only two were “up to the standard required”. Three weeks later, the dentist, Dr Morgan, examined every child and extracted 72 teeth!! Martin doesn’t specify if he did it in one day or not.

Martin also complained about dance events held at the school. He believed a few only interfered with his and the school’s belongings. One incident occurred when the wireless aerial was taken down, inserted under the window, and tacked along the mantlepiece with drawing pins.

Mary Faulkner (married Collins) replaced Martin in July 1944. She boarded at Whyman’s Hotel in Waratah. Mr Devlin, the bus driver, dropped her off at the school every morning. In the school record book, she referred to a broken window in the school room where water ran across the floor during rain, making the room very damp. After another dance, Faulkner was “utterly disgusted” to find on her return on Monday morning, after being away for the weekend, another window broken, charts and pictures torn down from the walls, the girls sewing interfered with, and the blackboard rubbed out. She warned that if “this is a sample of the manner in which the dancers conduct themselves, the dances will be discontinued”.

Faulkner noted that during the winter, there were several heavy snowfalls, on some days nearly six inches deep, which meant that the children at least two miles away could not get to school. However, she noted that the children missed a lot of work, and it is hard for the students “who are not brilliant” to catch up with their work.

Bev Cunningham (married Paton) taught in 1945, not starting until April; also boarding in Waratah at the hotel and travelling to and from the school via the daily Waratah to Burnie bus. She went home to Wynyard on weekends. She commented that the children are “very backward and manners need improvement”. Most of the 17 students came from sawmill working families.

Annie Lillias was one of the longest-serving teachers from 1946 to May 1949. Geoffrey Ling followed her in 1949-Dec 1949 and Charles Saville in 1950.

With the sudden resignation of Saville in August 1950, the school was closed, affecting 14 children who were not getting any education. The Waratah Council made representations to reopen the school or have the children transported to Waratah State School or Yolla Area School. In October 1950, the Education Department seemed to ignore those requests and wanted the windows at the school boarded “now that it was closed to prevent unauthorised entry”.

In June 1951, there was a proposal by the Waratah Council to use the Parrawe school building as a hall for local social functions. However, the Education Department rejected this as the building was urgently required at Somerset to “relieve the overcrowded conditions at that school”. The school building was relocated to Somerset in late 1951.

In 1955, the Education Department decided to sell the school site under a public tender. Before the sale, there were several enquiries regarding using the land and the remaining shed. Thomas Gillam, who lived nearby, wanted to lease the site. The Head Teacher at Waratah School wanted permission to remove and use the shed at Waratah for storage.

In 1956, the Education Department requested the Lands and Survey Department to dispose of the school site by public tender. The PWD was consulted and wanted the site as a stockpiling area. On 20 February 1957, the school site was proclaimed under The Lands Resumption Act 1910 as a PWD Reserve for stockpiling metal for roadworks.

Rabbits and the demise of Parrawe

By WWII, there was a great disappointment in the lack of progress of the Parrawe settlement. The rich myrtle forests were cleared on a face for farming in a selection boom earlier in the century. While the area grew good grass for cattle on rich basalt soils, it was roughly cleared with many remnant tree trunks providing a conspicuous landmark over the area. It did become the chief agricultural area of the Waratah municipality. The Waratah plateau struggled to support farming all year round due to its higher altitude. Guildford supported some rough grazing country on the difficult-to-remove native grasses.

One observer noted in 1945, “after 30 years of settlement the aspect of the rich, undulating land is a dismal picture. Conspicuous from the road the fire-blackened logs, the few cultivated areas standing out in pleasing relief”.

The main reason for this was the arrival of the rabbit. The first reference to rabbits was by grazier George Brown in May 1927. In 1933, Waratah Council believed the “comparatively few” rabbits near the town were “more of a blessing than a nuisance to residents” as they allowed numbers to increase across the district, including at Parrawe.

The only way to deal with rabbits was to trap or shoot them. By March 1934, alarm bells were ringing about rabbits rapidly becoming a menace. The rabbit inspector visited the area in July 1937, reported that rabbit numbers were rapidly decreasing, and declared “the pest was now under control”.

This may have introduced complacency as questions were asked a few years later about rabbit control, and the council had to restart control programs, but by then, it was too late. The Waratah Council did attempt a poisoning campaign in February 1940, with Thomas Lancaster appointed the temporary rabbit inspector to supervise the program. However, it didn’t achieve the desired results because of the failure of some landowners to poison systematically.

Allan Mather was shooting rabbits with a pea rifle in the winter of 1945. When he stepped on a log covered in snow, he slipped, and the gun discharged. The bullet entered his ankle bone and lodged in his heel. He had to go to the hospital to have the bullet removed.

With the introduction of bulldozers and other machinery after WWII to clear land, the Parrawe Progress Association suggested the government supply dozers to help the settlers affected by rabbits ravaging their pastures. They argued that the inability to break up their land and re-sow made it useless. The settlers were willing to meet the running and labour costs.

Shooting wasn’t worthwhile when skins were only 12 shillings a dozen for “first quality back country” rabbits, even though the best quality skins came from the Parrawe and nearby Hampshire, Takone and Tewkesbury regions.

With rabbits firmly entrenched, the long, slow demise of Parrawe took hold. Without wire fencing or myxomatosis, they quickly overran the district, destroying pasture. When Parrawe was at its peak in the late 1940s and early 1950s, even fielding a football team in the Waratah District Football Association, the district began to decline markedly. Farming was the first to fall, and then sawmilling followed. Farmers abandoned their land and sold up. Ec Hills was the last to live in the area.

It was not uncommon in many areas of Australia, where farming had failed because it was practised on marginal land or other forces limited its success, that planting trees on a large scale was encouraged. During and after the Great Depression, governments set up employment schemes for the many unemployed labourers – some of those schemes involved planting trees, particularly radiata pine.

While many pine plantations were planted in the Parrawe area in the 1960s, they were funded by private enterprise, not the government. AFH started their pine planting in the north-west in earnest in 1960 on abandoned farms around Tewkesbury and Hampshire. They decided to increase annual pine plantings in 1963 to meet the requirements of APPM’s new particleboard plant and pulp mill at Wesley Vale.

As well as Takone, abandoned farms in the Parrawe area were targeted. The first properties purchased were David Jordan’s (then owned by Percy Foy) 100-acre block, Herbert Neal’s 193-acre block, and Aser Smith’s 194-acre block in 1956. This was followed by Stephen Smith’s 190-acre block in 1960 (then owned by J. L. Buss), Jacob Smith’s (Bernard Spencer) 198-acre block in 1963, the two Turners’ blocks in 1967, and Wiff Campbell’s 197 acre block in 1970. In 1975, AFH bought the four Cumming Bros blocks – ex Stephen Smith, Saxon, Cole and Clement Hills. Alf Jone’s (Wynyard Sawmilling) 196-acre block was purchased in 1976. In 1978, AFH bought two properties from Francis Britt – ex Ivy Smith and Richard Smith.

There were also significant purchases in the 1980s by syndicates of landowners put together by local identity Peter Martin. Martin’s schemes were an early (un)managed investment scheme. The landowners tended to be Burnie professionals (lawyers, doctors, etc.) attracted to tax-deductible investments. Gunns eventually bought most of these properties in the 2000s.

In time, the people, the town, the sawmills, and the everyday human activities at Parrawe disappeared as the fertile acres were reclothed in trees again.

This is one of the more complex narratives linking many aspects of the area. I think it reflects well on the story and your developing knowledge and skill over this 20 year period.

I also had not seen the convention regarding the notation for a women’s maiden name followed by the married name. It makes sense.

Tasmania is still struggling with the delivery of education and I have reflected if many of the attitudes and behaviours of these small villages continues today, then it shows with a lack of respect for education.

Fascinating, Rob. My oath, those pioneers did it tough!

These days, though, even if one lives in a town or city, the general inaction by government bodies is just as evident and we citizens still manage to cry in our beer just thinking about politics.

Allan Jamieson

I drove through Parrawe only a few days ago (after a hike to Philosopher Falls west of Waratah) and, apart from a few rows of old macrocarpa trees, nothing hints at its settlers and this rich history.

As Andrew comments above, it is a complex story and, having seen part of it in the raw files at the Tasmanian Archives, I think you have done remarkably well gathering it into this narrative.

As I waded through the TA files, I could see that your current story could only ever be framed by the material you had. A lot that wasn’t ever documented or discoverable for this story would fill in the gaps and I hope you get an opportunity to gather more material for the more comprehensive and complete story you mention in your email.

As a direct descendent of Herb Neal, I have tinkered with our family history from time to time.

The history of Parrawe is fascinating with local links to Yolla, Henrietta, Waratah and Wynyard, giving me new information on our “Neal” family.

There has been a lot of work put into this project. Good job well done.

Patrick Neal.

Fascinating isn’t it?

This is Herb Neal my grandfather, your great uncle. Dad used to go there with him and grow potatoes. They would camp out at Parawee for weeks at a time.

Thanks Robert for putting this together.

I spent some time in Parrawe in the late 50s, along with Kelvin Nolan, falling and carting sassafras logs to Rob Robinson’s sawmill. There were some characters in Parrawe in those days – Ec Hills, George (Scrowger) Walker, Charley (Bunny) Doherty, Ted Burgess to name a few.

Good work and writing, thanks. The difficult climate and government (state and locals) inconsistent and poor decisions lead to what we have today.

I am an ancestor of HD Neal and Taylor’s long gone sawmills at Takone West.

My memories of Parawee relate to living there for five years in the fifties. Dad, Thomas Gillam, owned a 100 acre farm there cropping potatoes, and running a few dairy cows milking by hand and separating the milk, giving the skim milk to pigs while the cream was transported to the Burnie butter factory.

During the winter months, Dad trapped rabbits, he had twelve dozen traps and would go around them morning and late afternoon. It was not uncommon to trap over a hundred rabbits a day! He would sell the carcase to Beer & Kelton butchers in Burnie, transported them on the school bus. I don’t think that would happen today!

I recall he was paid 2 shilling and 6 pence a pair! (25 cents in today’s money). The skins were placed over a wire frame and dried. Neale Edwards the skin merchants collected them every so often.

I have memories of walking to Ec. Hill’s farm and helping with the potato harvest at the tender age of 10.

Summers there could be very hot and the winters very cold, many a day, school at Yolla was unattended because the road was snowed over, or a tree had come down over the road in the gorge during a storm.

I first visited Parrawe 45 years ago (heck that’s a long time ago) with Dick de Boer where we looked at some of the pine plantations he had developed. We also looked at the blocks the Pulp had purchased for further development.

We found it a bit of a struggle growing trees there because of the cold climate, particularly frost where trees initially struggled from whitegrass (Poa) competition.

I later read a paper from NZ FRI about the effect of whitegrass on the microclimate where it essentially radiates heat at night from the soil into the air, like cooling fins on a motor.

The solution was broadcast spraying with Atrazine creating a bare earth effect – it worked a treat. I didn’t have much luck initially growing Eucalypts there either.

I also vaguely remember buying stuff at the Parrawe shop but can’t remember who ran it.

Thanks Robert – a great read. I had a wry smile at the reference to Peter Martin and his (un)MIS schemes – promised so much and didn’t deliver…maybe a bit like all the other MIS schemes to come later.