Early trade in Maryborough

The port of Maryborough on the Mary River was significant, not only for the development of Maryborough itself but also for trade in south-east Queensland. It exported gold, hides, tallow, refined and raw sugar, rum, antimony and timber. Also, after the separation of the colony from New South Wales in 1859, Maryborough was declared a port of entry and necessitated the collection of customs on behalf of the government.

Coal was discovered in the nearby Burrrum district in 1863, and underground mines started at Burrum, Burgowan and Howard. The mine owners were keen for a railway line to their mines to offload their precious resources. Meanwhile, over time, the larger trading boats from Europe and British East India found it difficult to navigate the Mary River, as the river was only suitable for smaller boats with a shallow draught.

Around the early 1900s, the larger boats were unloaded at North White Cliffs on Fraser Island onto lighters, taking the cargo up the Mary River. But this was inefficient, expensive and time-consuming.

The other part of Maryborough’s trade problem was the charges for cargoes shipped from Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney to northern ports of Queensland were as low as goods shipped from Brisbane or Maryborough due to excessive shipping charges by the government. Consequently, orders for a large quantity of timber and coal went past Maryborough.

While a railway line was opened in 1881 to connect Maryborough to the goldfields at Gympie, by the early 1880s, ships were looking to offload their cargo or upload local stores elsewhere, and Urangan Point was favoured as Wide Bay’s answer to maintaining the trading of goods in the area.

Without any infrastructure to get the products to and from the anchorage outside the Maryborough port, there were limited options. There was no formed road to Hervey Bay until the 1890s. When a road was built, it was an arduous trip by horse and sulky.

A Maryborough resident summed up the situation in the early 1880s with an article in the Maryborough Chronicle:

“There is a lot of back freight from Maryborough in stores, bricks, machinery, timber, luggage, furniture, &c., &c. The natural advantages of Torquay and Torquay Bay are so great that the population, buildings, and carrying traffic of the place is sure to make rapid progress, to be measured not by years, but by months and weeks. In addition to the town traffic, the British India Company’s steamers and the large immigrant vessels from Europe which cannot get up the Mary will probably soon anchor at Urangan point, situated about 2 miles from the Torquay Ship Chandlery and General store. The coal trade will soon burst upon Maryborough with such a rush that the deepwater anchorage at Urangan point will become a pressing necessity, and then the railway will be run into Torquay as far as the point, and a jetty constructed”.

The coal trade was about to take off with a coal mine established at Torbanlea. In 1895, 30,000 tons of coal was produced by the mine.

The original aim was to have a rail line to deep water so ocean steamers could load coal, timber and other bulky products. A railway to deep water was considered necessary for the large manufacturers in Maryborough, as it was one of Queensland’s major manufacturing towns, hosting 73 industrial businesses. For many years, it hosted Walkers Limited, which built ships, steam engines, and large engineering equipment. Large railway workshops also maintained and repaired rolling stock and engines.

In the early days, Pialba was seen as a “fashionable ocean resort” where the local citizens from Maryborough holidayed, seeking a “change of air”. By the end of the nineteenth century, It had developed for tourists, offering more than just sea bathing and collecting seashells. However, the idea of a deep-sea port servicing the local heavy industries was still paramount.

The Railway

Immediately after the discovery of coal near the Burrum River in 1865, there were proposals to build a railway to Hervey Bay, but nothing resulted.

The idea of a railway line to Hervey Bay from Maryborough was first mooted in 1883 when a survey was carried out to service the local coal fields. The proposed line was 27 kilometres long but was never built.

In 1884, businessmen from Melbourne formed the Vernon Coal & Railway Company and lobbied for new legislation in the Queensland Parliament via the Maryborough and Urangan Railway Bill. They promised that they would build the line within eight months. The government had an option to purchase the line’s wharf facilities at cost plus five per cent of the value of the rolling stock and equipment after ten years. The bill was modified with the buy-out option being reduced to five years, and the line was to be built within three years.

The bill was approved that year, but by 1887, construction had not begun. The Vernon Corporation went into liquidation the following year.

In 1895, the Queensland Government passed the Railway Construction Guarantee Act, which would allow private enterprises to build railway lines, and government and local authorities would guarantee to bear half the losses or share the profits.

It led to the construction of a railway line from Maryborough to Pialba in April 1896 and was completed in March 1897 for £25,250 (millions in today’s dollars).

The official rail line opening ceremony was on 18 December 1896 as far as Pialba. At the time, the line was described as more of a luxury than a necessity. The line benefited the Pialba and Nickenbah sugar cane farmers to get their produce to market in Maryborough and played a vital role in the early development of Hervey Bay.

However, it didn’t solve the deep port issue. The expansion of the coal trade depended upon access to a deep port. Having a rail line to Pialba didn’t initially achieve that aim.

The only suitable deep port in the bay was at Urangan, and the locals soon lobbied for the line to be extended there. Surveys for a new line were carried out in 1907 and again in 1910. Approval was given in 1911, and construction for the railway extension was completed in 1913. While there still was no deep-water port, the coal produced in the nearby collieries was used locally as the companies failed to get export orders. The rail line, however, did help the sugar cane industry flourish and was also used for passenger services.

The railway extension to Urangan had several sidings which benefited the local farmers at Kawungan, Urraween, Nikenbah, Takura and Colton. The farmers could send their sugar cane, pineapples, milk and cream and other products to market via Maryborough.

At one stage, the Maryborough to Hervey Bay railway line was one of the most profitable in Queensland, but its use declined over the years.

The last passenger train to leave Pialba was 7 August 1972, with the line remaining open for freight traffic only.

The portion of the line between Takura to Urangan was recommended to be closed from Saturday, 1 January 1994, by a Queensland Government-appointed Rail Taskforce in its Report in November 1993. The railway officially closed on 30 June 1994, and the line was lifted in 1995.

The Pier

Once the railway extension to Urangan was built, the focus shifted to the deep-water port.

The deep water at Urangan was just outside a sand spit, and so it was decided a pier would be constructed to the deep water. However, it was during WWI and was a big financial undertaking.

The timber used for the pier was sourced locally. There is a common misperception that the piles were satinay (Syncarpia hillii) logs from Fraser Island. This isn’t true because satinay (known as Fraser Island turpentine until the late 1920s) was not favoured by sawmillers and was bypassed in the forests as it was prone to shrinking and warping after being cut into boards. Its marine borer resistance features were not discovered until the mid-1920s, when the actual value of satinay was fully appreciated.

Satinay has a mainland cousin called turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera, but was initially described as S. laurifolia). Mainland turpentine was much sought after as a hardwood, with its reddish-brown colour ranging to a deep chocolate brown and coarse, even texture with a straight grain. It is an excellent timber for dance floors. It is also used as plywood, laminated beams, bench tops, joinery and parquetry, boat building and wine casks. Because the timber is fire-resistant and highly resistant to termites, marine invertebrates, and borers, it was much in demand for marine piers and building foundations. During the war years, large turpentine logs over 100 ft long were sourced as piles for the pier from forests in Queensland, as well as grey ironbark.

The head section of the pier, with its sheds, was built separately, and the main stem of the pier was built out to join it. The total length of the pier was 1.3 kilometres over waters eight metres deep. It was officially opened in 1917 and called the Port of Maryborough.

Once the pier was completed, it was referred to as a white elephant, mainly because only six boats used it in the first seven years. The pier peeved Maryborough residents and business people, and they saw it not only as a serious competitor to its port but also struggled to obtain public funds for much-needed river improvement work because of the enormous expense on a pier they considered not “worth twopence”.

After 1929, the pier overcame the early political indifference as the export of bagged sugar and coal proved to be primary economic earners for the local economy. The bagged sugar came from the local sugar mills and railed to the end of the pier, and was loaded manually onto ships.

By the 1930s, the maintenance of the pier was a significant undertaking. A gang of four employees, including a diver, was responsible for ongoing upkeep. Unfortunately, the costs of maintaining the wharf far outweighed the use of the pier over its lifetime. Another issue was the use of a crane to load the ships.

The export of bagged sugar was phased out in 1958 after a bulk-loading sugar port was built at Bundaberg.

Coal mining ceased in 1967, and the last regular steam-hauled service occurred on 7 January 1967.

The Caltex Oil Terminal

By the 1960s, Caltex Oil Company were keen to build an Oil Terminal in the Wide Bay to service the Wide Bay industries. They favoured siting the terminal at Urangan to take advantage of oil tankers berthing at the Urangan pier.

At the same time the pier ceased hosting sugar bags and coal for export, Caltex took over the pier to import oil.

A site was chosen bounded by Elizabeth and Dayman Streets, which hosted large steel storage tanks to hold petrol, diesel and other petroleum products.

A steel pipeline was laid on the pier’s decking to transport the fuels directly from the tankers to the terminal. Three mooring platforms, called dolphins, were constructed in 1962 to secure the much larger oil tankers. One was hundreds of metres off the northern end of the pier, another a similar distance off the southern end and a third closer to the pier.

The mooring lines from the 15,000-ton oil tankers were ferried out by a custom-made vessel where the lines were securely fastened by two men waiting on each platform.

The end was close

The pier was closed to traffic in 1974, and by 1985, with Caltex’s new supertankers unable to navigate Hervey Bay, the Urangan Pier was permanently closed. Freight ceased on the railway line on 29 October 1991 when Caltex closed operations at their storage facility.

The Department of Harbours and Marine (DHM) was responsible for looking after the pier. They were increasingly concerned about the high maintenance costs. They were worried that the wooden piles supporting the pier had deteriorated beyond repair. The head of the pier housed disused warehouse buildings, loose railings and decking boards that were being vandalised. There were quite a few safety incidents, with people injuring themselves while walking on the pier and, in a couple of cases, falling through missing decking boards into the sea to be rescued.

In April 1982, Caltex reduced staff at their depot after the federal government removed fuel subsidy schemes. Rumours swirled that the pier would be closed to the public and dismantled. A “Save the Pier” committee of concerned locals was formed under the leadership of bait and tackle shop owner Bob Spring in August 1982. They tried to get permission to carry out a voluntary maintenance program to make it safe for fishers and the local public to continue to use the pier.

A local company, Cromere Pty Ltd, also had plans to turn the stem of the pier into a commercial tourist attraction, which included a restaurant and pool, but DHM didn’t support.

Just when the Committee organised a petition of 8,000 signatures to the Premier, Caltex announced it would no longer import petroleum to its Urangan depot via the pier from 31 December 1984. The state government announced the pier would close unless the Hervey Bay City Council would take over the responsibility for maintenance of the pier.

The Council was in no position to take on that role. Instead, they vigorously called on local developers and tourist operators to redevelop the pier, suggesting a new marina complex or even turning the pier into receiving cruise liners.

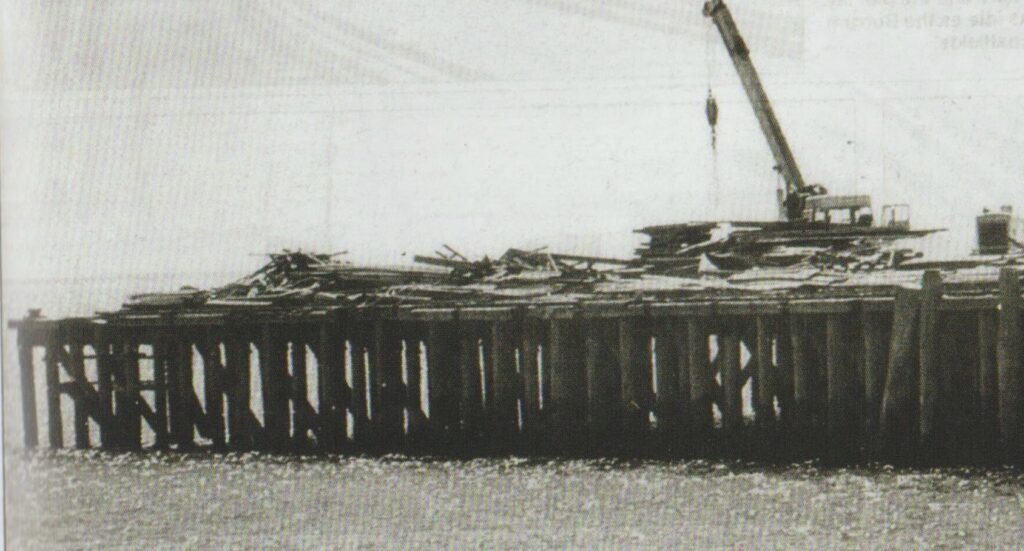

Immediately after the last oil tanker departed from the pier on 9 January 1985, the state government called for tenders to demolish the pier’s head 256-metre section. Local solicitor, angler and user of the pier, Barry Sheldon, got involved and helped the Save the Pier Committee become incorporated. He then wrote to the Minister offering to lease the pier head via the Committee forming a company.

Despite these strong representations, the government announced in June of that year who had won the tender for demolishing the pier head. To add salt to the wounds, the Minister’s reply to Sheldon was dated 22 July and regretfully advised that DMH could not consider the lease application because demolition work had already commenced.

The demolition took much longer than initially anticipated and was finally completed after nine months. At that time, the locals were galvanised into saving the rest of the pier. The Council negotiated a reprieve by seeking a two-year lease to carry out necessary maintenance works on the remaining stem of the pier to make it safe for future use. They had to wait until the demolition works of the pier head were completed.

That gave the Council and the Committee time to organise themselves, and they managed to win funding from the Commonwealth Community Employment Program to do the maintenance and restoration works on the decking and rails. They also raised $10,000 in public donations to help with a. working bee attended by over 60 people.

After completing the works, Sheldon, now President of the Committee, got the support of local media, the Lions Club and the Sportsman’s Club to hold a festival to celebrate the pier on 25 October 1986, where the pier was officially re-opened.

The festival went on to become a popular annual event. Still, unfortunately, the ongoing yearly cost of major works, such as dealing with replacing the pylons, was left to the Council, which could not provide the much-needed funds on an ongoing basis.

Two structural engineering reports commissioned by the Committee highlighted that the pier had a promising lifespan of 25 years if annual maintenance tasks on decking and rails were carried out. However, after seeming to survive Cyclone Fran in March 1992 without significant structural damage, a few months later, a couple of piles snapped and fell into the ocean. Quick repairs highlighted that another 15 to 20 piles would need to be replaced. A more major marine and civil engineering report recommended urgent repairs and the pier’s closure for safety reasons. While the $44,000 emergency works were completed from Council funds, further work was required at an estimated cost of $550,000.

The State Department of Transport entered the fray, arguing that the pier had to be demolished regardless of what works were carried out. They released a report recommending demolishing the pier in favour of a new structure with a 1.5-metre aluminium walkway for $1.2 million.

The concern for the locals was the re-emergence of the threat of losing the pier. The Hervey Bay City Council and the Maryborough Chronicle joined the fight to avoid any demolition works. Local politicians were lobbied to help raise funds for the much-needed restoration works.

On 30 June 1994, the Council announced it was purchasing the pier from the state government at a peppercorn rate, with the state contributing $250,000 towards the estimated restoration cost of $1.3 million. The council committed $300,000 per year.

The Committee decided not to disband and monitored the progress of restoration works to ensure the pier remained. After about half the pier had been restored in two years, a change of Mayor at the local government elections brought the pier’s future into the spotlight again. The new mayor didn’t support the spending of Council funds on restoring the pier – now estimated to cost over $2.5 million – without raising a special ratepayer levy.

A reader poll by The Independent newspaper confirmed strong public support for the pier without raising rates or a special levy. The council started a campaign for community financial support and state and federal government funding. The Urangan Pier Restoration Committee was formed to run a major fund-raising campaign. While $112,000 was raised, it was apparent this was not enough for the ongoing upkeep of the pier.

Sheldon and the Committee were worried about the dependence on the public and the lack of commercial business support. They put forward a petition to the state government. In March 1998, Premier Rob Borbidge announced a $500,000 grant as long as the Council committed the remaining $164,000 to complete the restoration costs for the next section of the pier.

Finally, the pier was saved and celebrates its 107th year this month. But for how long can it survive?

Thank you Rob for that “history” lesson for me.

The Pier certainly has some history and to think it was still being used for commercial business not that long ago is amazing.

I walk this pier every day and find myself drawn to its attraction and stunning views across the bay and over to the Islands.

Depending on prevailing weather and tides, there is something different in its appearance every day.

Fisherman are eager to try their luck along with the locals and tourists just out for a stroll to take in the views and the serenity.

Thank goodness people power won out in the end with the preservation of this iconic structure that deserves to still be a part of this area and its history.

With upkeep and maintenance let’s hope the pier continues to be a special place for many to explore for the next 100 years.

A great interesting story Robert, thankyou.

Having been brought up in a town that has a 1.25 mile long pier, I know the feeling and experience of ‘having a pier to walk on’ and how exhilarating it is.

Plus, learning about their histories, after they were never built as piers just to walk on!