Gold fossickers were the first settlers to the Evans Head area on the far north coast of New South Wales. Not finding gold, they turned to oyster farming and prawning, with Evans Head becoming Australia’s first commercial prawn port.

In 1919, an Italian immigrant, John Rosolen, built the first General Store. Others quickly followed, setting up a butcher shop and a bakery. John was a visionary, and in 1930, he initiated plans for an airfield at Evans Head.

In 1934, New England Airways applied to the New South Wales government to establish an airfield at Evans Head. Work commenced in April 1936, and after 150 acres were levelled, drained, and enclosed, it was approved for use by September of that year.

Initially, it was only used occasionally by small aircraft because Evans Head was a sleepy coastal fishing town. However, with the outbreak of WWII, the airfield grew dramatically. The threat of a Japanese invasion led to much speculation about forming the “Brisbane Line”, which would have made Evans Head the northern airbase from which to defend eastern Australia. Fortunately, the military did not implement this strategy.

In 1939, the RAAF resumed the use of the land for defence purposes. They utilised the civil aviation shed for fuel storage and conducted flood mitigation works to protect the airfield. They also carried out further work to extend the airport by sixty acres.

RAAF decided to establish the first Bombing and Gunnery School in Australia under the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS). It was colloquially called No 1 BAGS. The school aimed to train air observers, bombers, and air gunners in the theory and practice of bombing and air-to-air gunnery. They needed enough land to establish an airfield, camp area, officers’ accommodation, isolated bombing ranges, and gunnery ranges.

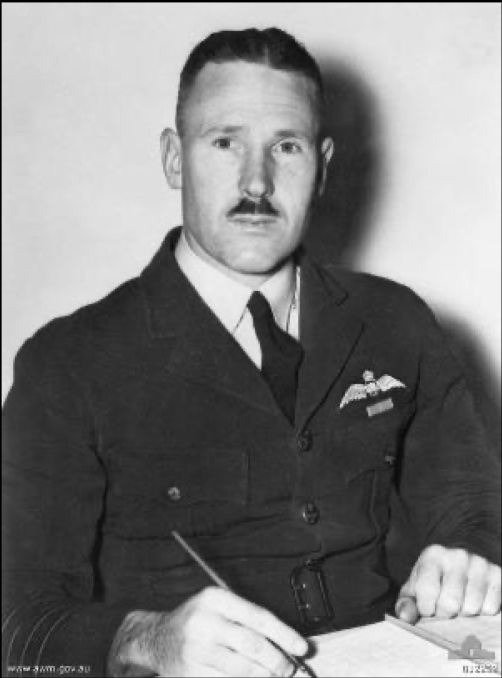

Sir Valston Hancock, Director of Works and Buildings in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), inspected Evans Head as a potential location for No 1 BAGS. He was very impressed and described the land at Evans Head as:

“…one of the most natural bombing and air firing ranges in the world”.

The new base

Based on Hancock’s assessment, a quick decision was made, considering war had already broken out in Europe. The Commonwealth acquired an additional 600 acres of land. The construction of the new base was rapid, and was ready to accept its first trainees seven months after construction began. Substantial engineering works included roading, new bridges and culverts, drainage and water supply from bores. Large gravel areas were established for aircraft use. Power was supplied from Ballina.

The RAAF established extensive bombing and gunner ranges to the north and south of the base and a sea leg to the south.

By the war’s end, it was the largest training base in the southern hemisphere, hosting Australian, English, and Canadian pilots. Its impressive four lengthy runways, associated taxiways, and tarred hangar aprons were its distinguishing features.

In late 1941, with Japan entering the war, the proximity of RAAF Evans Head to Brisbane made the base an important defensive asset in the event of an attack. RAAF built 19 gun pits on the airfield equipped with .303 Vickers machine guns. They also engaged aircraft in coastal surveillance.

The Air Force erected as many as 17 Bellman hangars. Also, a substantial marine search and rescue unit operated from the town wharves. There was also accommodation for up to 1,400 personnel, a hospital, garbage and sewerage services and recreational activities.

Bombing and Gunnery School training

At its height, No. 1 BAGS used 70 Fairey Battle aircraft with Wirraway and Avro Anson aircraft arriving daily from Amberley RAAF base in Queensland for bombing practice.

Due to wartime constraints, RAAF restricted each course to an intense four weeks, where trainees received complete bombing and air gunnery schooling. Part of their training was learning how to strip and assemble aircraft machine guns – the .303 Vickers gas-operated machine gun and the .303 Browning machine gun.

Trainees practised aerial combat by firing from a Fairey Battle. The British company Fairey Aviation built these single-engine bombers for the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1937, using them in the early days of the war. It was a two-seater plane – pilot and rear gunner, with the latter having one free gun on a ring mounting. However, they were already obsolete at the outbreak of WWII for being too slow and limited in range as a heavy bomb load weighed them down.

They were shot down in droves by the much faster German aircraft during early fighting in France and western Germany. They were withdrawn from active service by the end of 1940 and restricted to a training role. Eighty were used as training aircraft at Evans Head, mainly for bombing and gunnery practice. Trainees fired a machine gun at a drogue, a long cloth target towed one hundred yards behind another plane flying beside them. Speeds were varied so they could learn about deflection or the curve in the firing line of the bullets.

The other aircraft used at the training facility was the Beaufighter or “Whispering Death”, which was a regular visitor and used in mock attacks to test defences.

The Evans Head training base trained over 28,000 aircrews over three years. Most trainees that graduated went to Bomber Command in England. One of the trainees was actor John William Goffage, better known as Chips Rafferty.

More than 1,000 RAAF personnel (out of over 5,500) who trained at Evans Head were killed during the war, some during training.

Air Observers School

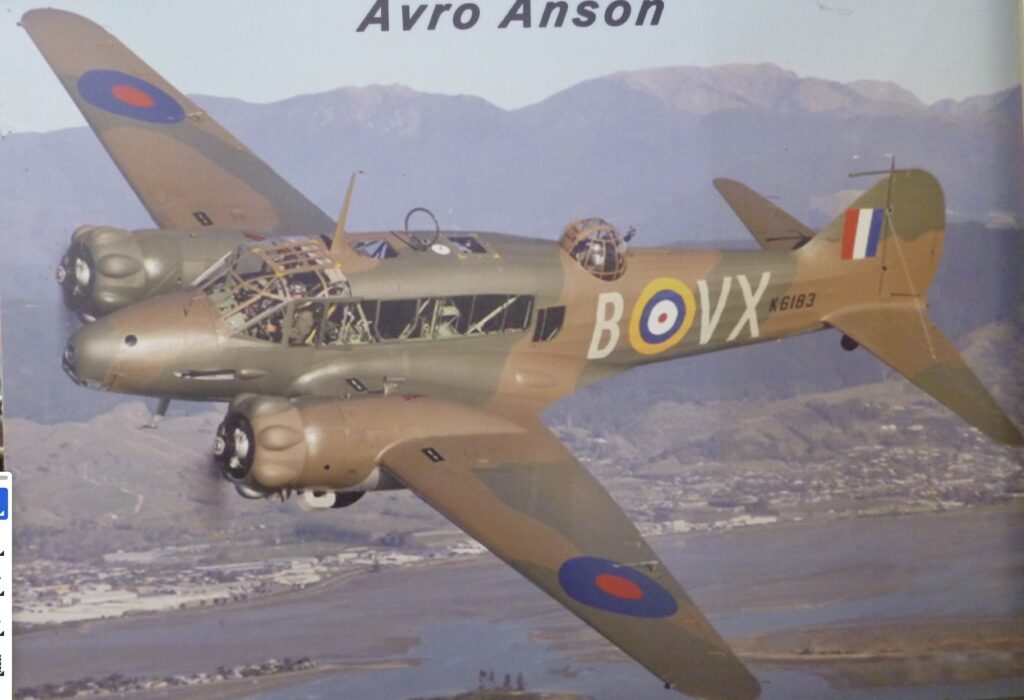

By March 1943, the British Air Ministry realised they had an oversupply of aircrew, and consequently, they disbanded No. 1 BAGS in December 1943. They were replaced immediately by the Air Observers School (AOS) which was relocated from Cootamundra to Evans Head the same month. Some 1,496 personnel and trainees arrived. As well as being established to train Air Gunners and Bomb Aimers, the AOS also trained Navigators and Air Observers. The AOS trained over 630 personnel using Ryan, Tiger Moth, Wackett and Anson aircraft.

However, it was the Avro Ansons that was the principal multi-engine aircraft trainer used by AOS. British company Avro developed the Anson in the mid-1930s. The RAF called tenders to build a maritime reconnaissance aircraft. Avro won, and they ordered 174 Anson 652A aircraft, naming the plane after the British Admiral George Anson.

Unfortunately, the Anson never excelled in its design purpose and by the time it entered service, it was already obsolescent and vulnerable to fighter attack. However, its benign handling characteristics, ease of flying and stable platform were recognised by the military as an excellent training aircraft.

While the RAAF mainly used it for navigation exercises, Ansons were one of the very few, if not only, aircraft that was involved in almost every aspect of military aviation training. Pilots, navigators, air gunners, bomb aimers, wireless operators and observers used the Anson as their training aircraft. Groundcrew, such as fitters, mechanics, electricians, and armourers, all learned their craft on the Anson. At any time, there were 80 Ansons on the flight line at Evans Head.

They were affectionately known as “faithful Annie” by the Australian trainees. The Anson has a special place in RAAF history, with more in service than any other aircraft.

The training school was disbanded on Victory in the Pacific Day on 15 August 1945.

Volunteer observers

Around 33,000 civilians were in the Volunteer Air Observer Corps around the country. One such Corps operated at Evans Head at the aircraft tracking table. Made up of mainly local women, they would travel from nearby towns to volunteer. Technology today eliminates the need for such a group, but they played a vital role during WWII.

They provided an immediate means for the country to establish some form of air observation capability, particularly during the real threat the Japanese posed across northern Australia during 1942-3.

In 1941, there was only fundamental radar coverage over a few centres in Australia.

Eleven-year-old Joyce Craig (nee Dickinson) and her family enlisted as official plane spotters from their farm home at Knockrow, near Evans Head, as they were only one of two households in the area with a telephone. They were armed with binoculars and a poster of different warplanes. The Dickinson family reported all aircraft sightings 24 hours daily for five years.

Military aircraft crashes at or near Evans Head during WWII

The following is not a complete list, and I welcome any additions. Also, some incidents have very few details.

The weekend of 18-19 January 1941 was a tragic two days for the RAAF training school. On Saturday, a bombing aircraft on gunnery training with five crew failed to return to Evans Head after flying over the unoccupied country between the Evans and Clarence Rivers during a wild thunderstorm. After an extensive search involving RAAF and local residents, the wreckage was found at the head of a gorge the next day. All crew died in the accident.

On Sunday, a Wirraway ploughed into the steep mountainside in a rugged range near Barker’s Vale. The plane was heading from Amberley to the Evans Head Aerodrome for training. Two trainees died. Two local youths clambered through the rainforest to find the wreckage site. They found the plane lying with its nose buried deep into the side of the mountain. The fuselage buckled towards the engine and no survivors.

In 1942, a plane crashed in the ocean near Byron Bay, killing all ten aboard.

On 6 April 1943, a Fairey Battle crashed 18 miles south of Evans Head in a swamp. Later that year, on 26 October, a Lancaster crashed when trying to land at Evans Head. Due to a change in wind direction, the plane overshot the runway. The pilot tried to miss a ditch and a fence without success. One wing struck the ground, and the impact damaged the port’s outer engine and the undercarriage. No one was injured in the crash.

On 22 May 1944, an Avro Anson crashed during a navigation training exercise one mile east of Knockrow Post Office, near the Pacific Highway, about 10 miles south of Ballina, killing the four crew members. There is a Memorial at the crash site on the highway, which the Ballina RAAF Association maintains.

The next day, the pilot, Flight Lieutenant Ernest Shackell’s father, stated that his son:

“…recently complained that he was flying too much and on the Sunday before his death said he didn’t know how he would get back as the plane was only hanging together”.

On 10 November 1944, two Beaufighters collided, and both went into sea 14 miles south of Evans Head. About March 1945, a Mosquito crashed at Evan Head, but minimal details are available.

After the war

After the war, when AOS was disbanded, a Care and Maintenance Unit took over the airfield, and the responsibility of the airfield was passed to the Department of Civil Aviation, ending RAAF use and occupation. Throughout the late 1940s, most aerodrome buildings were dismantled, destroyed, or transferred to other locations. One location was a short distance from Camp Koinonia, a retreat for spiritual growth, camping, recreation and training run by the Northern Rivers Baptist Association.

When RAAF looked to dispose of the site after the war, they noted that Evans Head Memorial Aerodrome contained approximately 27,000 acres of land, which included 344 acres of Commonwealth-owned land, a 243-acre explosives area, and the remainder was north and south bombing land.

From 1947, the aerodrome was used by Butler Air Transport for commercial aviation and in 1952, the Department of Defence handed over the airstrip to the Department of Transport. Woodburn Shire Council then gained control of the airfield under a Local Airport Agreement with the state government. All commercial activities ceased in the mid-1950s when they were transferred to Casino.

The airfield remained the property of the Department of Transport until 1992 when Richmond Shire Council gained ownership. They downgraded the site’s flying status, which could only be used by several types of light recreational aviation craft and as an emergency landing ground. In 1992, the first Great Fly-In for recreational aviators around Australia commenced during Christmas, attracting all aircraft types. It has since become an annual event. The Evans Head Memorial Aerodrome has also focused on war commemorative events held in Evans Head.

Since Richmond River Shire took control of the airport, its future has been threatened several times by residential developments approved by the Council but in breach of the transfer deeds preventing development, which may be adversely affected by aircraft noise. While a section of the extreme southern portion of the airfield was excised in the late 1990s and subdivided for residential housing, veteran groups and sections of the local community roundly criticised the Council’s decisions.

The runway remained in use until June 2012 with no lighting and was only suitable for recreational and general aviation during daylight hours. Since that time, it has been decommissioned, but it is still used for model aircraft.

Evans Head Military Museum

Today, the airfield is home to the Evans Head Memorial Aerodrome Heritage Aviation Association.

Seventeen Bellman Hangars were built at the Evans Head Aerodrome. They are a British design introduced by Sir Valston Hancock, the first commanding officer for the base. They were modified for Australian conditions and manufactured in prefabricated sections by BHP.

The Bellman Hangar was an excellent example of an innovative approach to wartime needs. The start of WWII saw the need for mass-produced, easily transportable buildings erected by unskilled labour. While prefabrication wasn’t new, prefabrication during the war utilised the methods of mass production-line construction from America. It provided a system that could produce huge quantities in a relatively short time.

In September 2011, the Defence Minister announced that the government would retain 13 iconic F-111 fighter/bomber aircraft for public display, with six available for loan to Australian aircraft and historic museums. RAAF retired them after 37 years of service. The F-111 aircraft came into service in Australia in 1973 and used the Evans Head Bombing Range frequently for practice. Their primary role was as a long-range precision strike and reconnaissance aircraft. Their long-range and weapons capability and all-weather and low-level terrain-following radar gave it a unique strike capacity for which no comparable replacement has been found.

The Evans Head Memorial Aerodrome Heritage Aviation Association was formed to organise hosting an F-111 at Evans Head. They were successful and made plans to use the one remaining Bellman Hangar to host the F-111. The hangar was dismantled in 2013, sand-blasted, repainted and rebuilt with new cladding. The F-111 was transported from RAAF Base Amberley by trucks and had to be partially dismantled with wings, horizontal stabilisers, fins, and a rudder removed to enable the safe shift of the aircraft.

The lone Bellman hangar houses an impressive display in the Evans Head Military Museum. The museum has a significant amount of informative and historical material on its walls and display boards and an impressive display of various wartime planes associated with the airfield.

Thanks Rob,

I lived for three years at Evans Head when I worked for FEA. I knew a little bit of the history but you have filled in a lot of the gaps.

Great read and brought back fond memories of my time at Evans Head.

Cheers Mike

Another good read, thanks Robert. Always good to read the tidbits of Australian efforts in the 2 world wars.

Hello Robert, an interesting part of the WW2 operations I was not aware of.

My dad attended the Initial Training School at Bradfield in Sydney, after joining the air force in January 1943. He then went to the Wireless Air Gunners School at Parkes. Then across to Port Pirie to the Bombing and Air Gunnery School.

The air gunnery training was done with a WW1 vintage Lewis light machine gun. A few of the live firing flights (maximum of 200 rounds) were incomplete due to no drogue, drogue was lost, the drogue collapsed (twice), the magazine front catch being unserviceable and the extractor spring breaking.

In January 1944, he left for England to complete his wireless operator air gunnery training. Thankfully, with the declining bomber crew casualty rate, he did join 460 Squadron at Binbrook until April 1945. He made four operational flights in late April and early May. They were all food drops over The Hague, Rotterdam, Leyden and Rotterdam again.