During our trip through western New South Wales in March 2022, we saw significant numbers of feral goats. These goats were everywhere, spanning from Broken Hill east through Wilcannia and Cobar onto Nyngan, covering over 600 kilometres in mulga country.

We had an overnight stop on the Barrier Highway at the Meadow Glen Rest Area, about 60 kilometres west of Cobar. Goats swamped me during a twilight walk in the surrounding bush to find mobile reception on a nearby hill. Usually, land management issues are hidden from the public, but not so with goats.

Freely roaming feral goats are a common sight for travellers beside highways and roads in western New South Wales. They don’t discriminate where they wander if the feed is around. They happily walked on the Barrier Highway, simply idling off to the edge when a road train thundered past. There are also considerable populations of feral goats in western Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia.

Their omnipresence led me to wonder just how bad the feral goat problem in Australia is and what, if anything, is being done about them.

The feral goat problem

Goats are native to Europe, Asia, and Africa and have been domesticated for thousands of years. They supplied milk on the sea voyage for the First Fleet in 1788 as mariners knew the value of the “poor man’s cow”. It is believed that 19 goats stepped onto the shores of Australia after that trip. For many decades, goats were the much-appreciated sole source of milk for early settlers in harsh tropical climates, where poor-quality pasture and high humidity did not suit dairy cattle.

Early settlers, miners and railway construction workers introduced them to inland areas, quickly establishing feral populations. They have been part of our landscape ever since. Today, New South Wales harbours over 5.8 million wild goats, predominantly descended from cashmere and Angora breeds.

Rangeland goats are a composite breed now naturalised to Australian conditions and no longer bear any resemblance to the original breeds of domesticated goats introduced at European settlement. Like rabbits, cats and foxes, goats haven’t become survivors of the Australian bush by chance.

Goats are considered pests due to their hardiness and rapid breeding. They cause environmental damage by destroying soil from their hard hooves and they strip leaves from shrubs and trees. They also compete with livestock and native animals for food. With uncontrolled grazing, goats can eliminate many legumes and forbs from a pasture, thus reducing the profitability of pastoral and agricultural industries.

Despite these issues, goats have adapted well to Australian conditions, surviving droughts better than sheep and cattle.

Goats are browsers as well as grazers. They require a diet rich in forbs and the leaves of woody species, which are higher in protein and minerals than grasses. Even in the driest conditions, they can scavenge on any available vegetation.

Dealing with the problem

In the early days of goat control, shooting was the preferred option. In the semi-arid woodland of Victoria’s Murray-Sunset National Park, volunteer sporting shooters have been used to cull numbers since 2003. Several other Victorian national parks have also seen aerial and ground shooting rolled out.

Goats were a problem on South Australia’s Kangaroo Island. Gut samples of the island’s goats found they ate over 70 native plant species. About 90 per cent of what was found in the stomachs of the island’s goats was drooping she-oak, the primary food source for the endangered glossy black cockatoo. Consequently, in 2005, authorities decided to remove goats from the island. In terms of area, it was the largest goat eradication attempt in the world. They shipped “Judas” goats with radio collars to act as traitors. It made it easier to find goats for culling.

The effort paid off. In 2018, rangers recognised that they had successfully removed the goats – the largest island in the world to achieve that feat.

It has been noted and studied that feral goats constitute a significant problem where dingoes and wild dogs are absent. There are now calls to re-introduce these top predators back into Australian ecosystems to control introduced pests such as goats, foxes and cats.

However, shooting goats and leaving them to rot is seen by many as a wasted opportunity.

The Goat Industry

In the last 30 years, pastoralists have seen goats in a different light.

Rogue operators were the main operators who illegally mustered goats from neighbours and Crown lands, cutting fences and causing mayhem. While trying to control goat numbers was a positive, all it did in the early years was attract every carpetbagger and petty criminal west of the Dividing Range.

Thankfully, in the 1990s, some farmers started interbreeding the feral goats with the South African Boer goats to improve their size and eating quality.

Others blended the ferals with the woolly angora goats, providing meat and mohair fleece. The mohair industry goes back to the 1970s. At its peak in 1987, the sector produced one million kilograms, but the fibre fell out of favour, and the market shrunk. Although there was a revival in mohair fleece through improved technology, that is not the main game.

The high live-weight price and demand for goat meat export opened a lucrative goat meat industry. Increasingly, goats are brought in from the wild, fenced off, and fed until they reach the ideal market weight of around 25 kilograms.

About a decade ago, when I used to travel to south-western Queensland for work, a farmer near Cunnamulla struggled to survive. His property was too small to make money from cattle or sheep, and he didn’t have other properties to run off. I saw firsthand how he had turned to farming goats.

He would round up free-ranging feral goats that came onto his property, shoot them, and sell the meat. Revenue from goats was his only source of income. These days, many abattoirs take the goats to process their meat for sale.

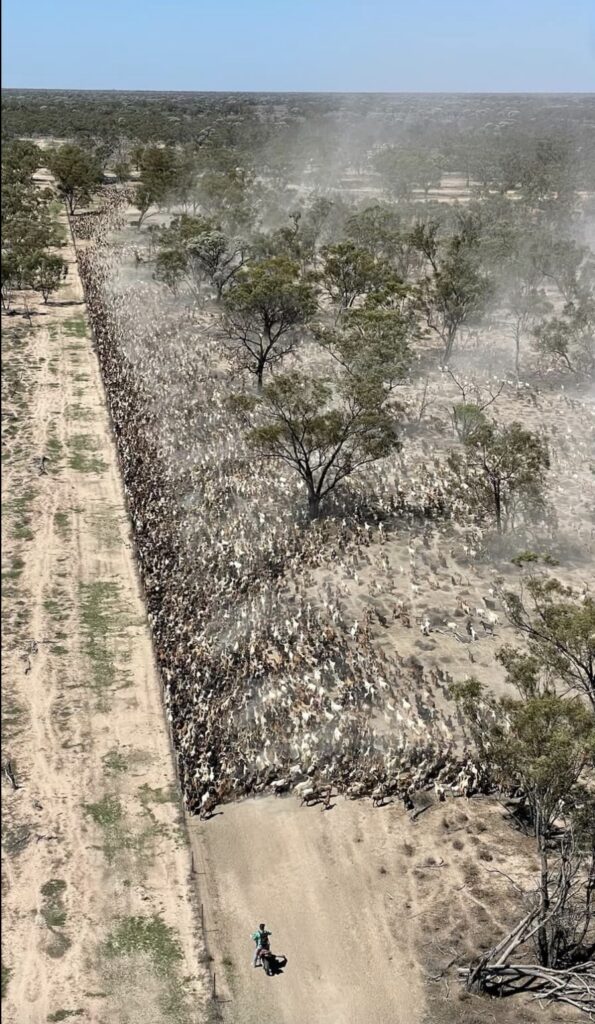

He was not alone. Many farmers in western New South Wales and Queensland have given up on cattle and sheep and concentrate on rearing what the goat industry calls “rangeland” goats. Before the last drought, Dan Muenster from Congarrara Station near Bourke in north-west New South Wales herded over 80,000 goats worth $8 million during the first quarter of 2017.

Prolonged droughts, a drop in sheep meat and wool prices, and poor export prospects have made goats valuable. Goat meat earns around $10 a kilogram of carcass weight compared to $7 for a kilogram of lamb and just $5 for other types of sheep meat. One of the goat’s advantages is the price of its meat is not dependent on the animal’s age.

Goat meat has been in high demand as it plays a vital role in many cultures, particularly religious and traditional family events. Because of its low fat and cholesterol content, goat meat is popular worldwide and suitable as a stewing meat, such as curries, in Indian, Pakistani, and Nepalese cuisines. Australia exports more goat meat than any other country. The rangeland goat comprises 90 per cent of the goat meat processing industry.

The goat export meat market is worth nearly $250 million to the Australian economy. The USA, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and the Caribbean are among the principal export markets for Australian goat producers. The USA imports more than half of all Australian goat meat due to the increase in the Hispanic population, and they can’t get enough goats.

Modern Management Practices

To meet the strong demands and ensure the continued development of the rangeland goat industry, producers have moved away from opportunistic harvesting to managed production systems. This involves reducing the buck population within the mob and only retaining or introducing quality bucks for breeding purposes. Does or nannies may also be culled if breeder numbers are sufficient.

Cluster fencing – perimeter fences surrounding a cluster of properties – originally used to exclude dingoes from sheep production areas, now supports goat production operations.

Farmers prefer wide-framed, shorthaired goats for better carcass weights and consistency. In 2021, the Queensland Sheep and Goat Meat Strategy was developed to capitalise on the expected doubling of production value.

Advantages and challenges

For western farmers in New South Wales, there are many advantages to stocking goats as livestock and turning it into a business. They are inexpensive to start with requiring minimal input costs. All a farmer must do is muster a herd, put them behind a fence and manage them. Unlike sheep, goats don’t suffer from fly strike or skin cancer and don’t need shearing. They are also easier to manage at sale time, with a single price regardless of age. Abattoirs take a carcass weight down to six kilograms compared to sheep, which must be over 16 kilograms.

However, goats need better infrastructure, including taller fences with barbed wire at the bottom to stop escapes. Most rangeland goat producers start with one paddock close to the yards and eventually move outwards.

Goats also need adaptive multi-paddock or rotational grazing to maintain legumes, forbs and woody species.

Despite these challenges, goats remain a viable option for many farmers.

Environmental and economic implications

However, there have been arguments that simply harvesting goats is not an excellent long-term environmental solution. They should be farmed under controlled conditions, like sheep and cattle, or eradicated. While eradication is impractical in vast rangelands, economic incentives have driven mustering and controlled populations in limited areas.

The other reality is that the western rangelands of New South Wales have been significantly impacted, some would say irreparably damaged, by historical overgrazing by sheep and the impacts of rabbits. Any consideration of environmental solutions has to focus on future management options, rather than a romantic notion of recreating historical museums that national parks and environmental groups hold onto dearly and fail miserably in attaining.

The numbers of rangeland goats was in the millions five years ago but declined because of management programs and unfavourable weather during the drought that ended in late 2019. However, herd numbers have increased as farmers become more selective and adopt traditional “behind the wire” operations on fenced farms.

Goat keeping is getting popular, and so is weed control

Some farmers use their earnings to buy properties with better farmland for breeding and fattening goats. This controlled environment reduces environmental impacts while maintaining profitability.

Goats are known for their unique taste and high nutritional value. Goat meat has a reputation for being characteristically lean and tasty. Goat’s milk and cheese are sought-after commodities. While most goat farmers are buying and breeding certain strains of goat for their specific qualities, some farmers in western New South Wales are getting their goats from the free-roaming feral herds in combination with Toggenburgs. They want goats that can survive in the dry heat conditions in the semi-arid country.

Dairy goats can produce uniquely Australian flavours based on the trees and shrubs they graze on. For example, acacia shrubs and trees make a slightly citrusy flavour styled on an ancient Israeli cheese from a desert region.

One farmer supplies cheese to world-renowned Mildura chef Stefano de Pieri to move away from what de Pieri says is the blandness of the traditional cheese market. This is partly due to the stringent regulations on making local cheeses, such as pasteurising and placing plastic packets to last forever. He believes his customers prefer fresh, clean and crisp-tasting cheese.

Artisanal goat cheese making sets itself against the big industrial cheese complex in producing a tasty, quality product free from constraints the major producers face. Most goat milk production is through pedigreed dairy goats such as Toggenburg, Saanan and British Alpine, not rangeland goats.

In Tasmania, we had a Saanan goat as a pet while we lived on an 18-acre property. Sylvester was borrowed to eat out a tiger snake-infested paddock chock full of blackberries near the house and the chook pen. It was a simple proposition – just throw the goat into the middle of the blackberries, and it will eat its way out. It didn’t quite work out that way, and Sylvester became the lawnmower for our 200-metre driveway. Realising now that they are browsers dependent on woody plants, I can understand his penchant for eating flowering thistles and anything else in the extensive garden around the house when left to roam on the weekends.

Because of their ability to remove vegetation, goats have been used to manage inaccessible areas, particularly on railways. A herd of goats “annihilated” an overgrown patch of weeds near Tully in northern Queensland in just four weeks. Queensland Rail is looking forward to the goats replacing slashing and herbicides.

Goats show land managers that they could be a better option than machinery and chemicals in dealing with weed infestations. However, for some reason, they are not considered an option for dealing with the myriad of weed problems in national parks.

The dilemma

When a pest is turned into profit, are they still considered feral? The issue continues to create conflict between pastoralists who rely on opportunistic goat harvesting to support their businesses and environmentalists who are keen to protect biodiversity from the impact of goats. The reality is that the eradication of goats is only feasible on relatively small islands, peninsulas and isolated habitat patches with low risk of re-colonisation.

Treating goats as both a pest and a resource creates a dilemma. When farming goats is profitable, there is little incentive to remove all of them, leading to accusations of deliberate releases to maintain breeding populations. Effective management requires efforts that are not solely dependent on market forces.

Despite proving to be an economic saviour for many rangeland farmers and leading to a noticeable dent in the numbers of goats in New South Wales, where fewer than two million head were estimated in aerial surveys immediately after the last drought – the lowest numbers in decades – feral goat numbers have rebounded as conditions have become more favourable.

While utilising an economic imperative to deal with the goat problem is a good thing, the fascinating friction between these hardy feral animals’ money-making potential must be weighed against the damage they cause to the landscape.

Many pastoralists from western Queensland and New South Wales would have gone bankrupt without the feral goats and are supported by the government. Where once pastoralists employed shooters to kill the goats, they now muster them for a profit. In some places, over 4,000 goats worth $250,000 can be herded in half a day using helicopters. The goat export market was valued at $242 million in 2021.

The high price for goat meat has driven mustering and successfully controlled goat populations. But only in limited areas. Additionally, goat meat prices dropped significantly in January last year to $3.25 per kilogram carcass weight, so it is difficult to know what direction the export market will head.

But it is not an option open to all in the outback. In South Australia, it is a very different situation. The state has always shot goats to minimise environmental damage, especially in the Flinders and Gammon Ranges. While South Australian pastoralists can muster and immediately sell the goats, they can’t keep the animals behind fences to breed and feed, unlike their interstate counterparts.

The crucial issue of mustering goats for economic incentives is that numbers may only be reduced temporarily. Plus, there may not be any incentive to remove all goats as pastoralist’s income could be dependent on future harvesting.

The Goat Industry Council of Australia argues that persisting with the term feral and highlighting environmental degradation limits the industry’s growth. On the other hand, it is argued harvesting unmanaged goats for a commercial return is a barrier to dealing with the environmental damage they cause, particularly as goats don’t respect tenure boundaries.

The common refrain is, “we will never get on top of the feral goat problem while they are treated as a commodity for some rather than a pest”. Critics are always happy to criticise private landowners or leaseholders when it comes to gaining money as part of dealing with the feral goat problem but are silent when that option is not employed, goats run rampant across the landscape, and governments do very little about the problem on lands under their control, such as national parks.

Many strategies have been adopted depending on the situation. However, the reality is market forces dictate methods of goat control. When prices are reasonable, goats are harvested. When prices or densities are low, little control occurs.

A discreet population of goats can double in size every 1.6 years. Approximately 35 per cent must be removed yearly to maintain the current population. While feral goat management can be more effective in areas suitable for culling, it is a tricky proposition in the rangelands without economic incentives. Additionally, controlling predators, notably dingoes or wild dogs, and supplying water for sheep has provided a favourable environment for goats.

Interestingly, the South Australian government has legislation that specifies landowners as responsible for the control of goats. Still, when it comes to public land they are responsible for managing, they rarely comply with their legislation outside of the major preservation areas.

Concluding remarks

I don’t know the best solution to the feral goat issue in Australia. It probably requires a combination of strategies. We have a serious feral goat problem and are struggling to get on top of the problem. On the one hand, dealing with the problem through economic incentives is a plausible management option, but how far does it go in controlling goat numbers in the long term, and what incentive is there to reduce their numbers?

On the other hand, the obsession with eradication as a means of controlling goats is impractical over the vast rangelands. While shooting has been successful in some instances, is it an enduring option?

I know there are unique opportunities to try and get on top of the problem. But will they be effective and long lasting?

As we ponder the best management strategies on former sheep properties in the rangelands, the monuments to the good old days of the golden fleece – the shearing sheds – now stand silent. For over a century, wool was the country’s main export and the source of Australia’s national prosperity. After the gold rush, the wool industry helped Australia reach one of the highest living standards in the world.

In the early 1990s, many farmers decided to sell their Merinos off the back of the wool floor price crash. Some went into cattle farming, and some harvested feral or rangeland goats.

As pastoralists adapt to changing markets and environmental realities, the question is can they survive this century by riding on the goat’s back?

Dear Robert,

Another terrific article, thanks.

There are many interesting goat stories from Western Australia, including their eradication from some important island nature reserves back in the 1980s.

Twenty years ago there were massive numbers of feral goats in the rangelands. Many stations, having been forced out of wool growing, survived only by mustering goats and exporting live animals to the middle east.

However, there was an unexpected outcome of the collapse of the wool industry in the rangelands. Control of dingoes and wild dogs was no longer deemed necessary and their numbers increased … and their main prey was the goat. Because they mainly ate nannies and kids, the feral goat herds gradually became comprised of old bachelor billies, and these herds soon declined in numbers.

On top of this, many former sheep stations were acquired by the government and are now managed as nature reserves. Remnant goats in these areas are routinely shot.

The general observation these days is that feral goat numbers are low in the WA rangelands, and declining – thanks mainly to predation by dingoes and wild dogs.

Kind regards

Roger

Thanks Robert. An interesting topic.

I was involved some 30 years ago as Manager of Environmental Protection for a conservation estate of some 35 million hectares, some of which was being degraded by goats. At that time the Agricultural Protection Board had a policy of eradication of goats, mostly by aerial shooting, whereas the pastoralists were harvesting goats and selling them for 3-4 times the value of sheep.

Guess who won out?

On the conservation estate we used some aerial shooting, capture on waterholes and limited ground shooting by professional club members, especially where goats were competing with rock wallabies for feed.

We also used goats in radiata plantations to graze out blackberry infestations. But then there was a dramatic change in goat numbers. The APB program of widespread aerial baiting for wild dogs/dingoes declined, there was a major shift from sheep to cattle and dingo numbers increased, including in conservation areas, where they should be a natural part of the ecosystem.

Quite soon the dingo had a dramatic effect, targeting the nannies and kids. A pleasing biological solution and conservation outcome.

Regards

Frank

I am concerned with the Federal Labor government destroying livelihoods in stopping the live sheep trade, however goat exports by live trade won’t get up.

I think small abattoirs and sustained management of goats and rotational grazing is the go. Value adding is important, produce in Australia, as well as animal treatment standards.

There is no mention of fire management and goats. NSW Rural Fire Service is using goats in a paddock trial, note whilst completing 0.6 % prescribed burning of forested areas per year.

I suggest reading NSW Department of Environment and Heritage website regarding the cooperation with feral goats – a common sense approach.

I don’t know if goats can control Hudson’s Pear, I suspect not. This is a massive risk to Australia.

Your goat story is most informative, well done.

The story reminded me of an old fellow I knew in Dalby in the early 70’s. He had owned various farms in his time and one day he offered me some advice. He said, “Peter if you are going to farm animals never touch sheep, you will spend your life repairing them. Farm goats, no maintenance”.

A good, thought provoking article.

It seems to me to make a lot of sense to both farm goats – and improve their genetics to make them even more desirable.

My concern with all this is that if there is ever a downturn in the goat industry beyond the ability of an export trade to cope with it – for whatever reason (eg, input costs, restricted points of slaughter, war) – the farmers concerned will have no alternative but to open the gate and flood the environment. In an instant, the profitable animal becomes feral, again.

Perhaps an interesting parallel was the farming of deer in Qld, including the instance where persons legitimately farming deer up to the downturn in the venison trade in the 1980’s merely opened the gates and flooded the forests (and western Brisbane) with even more feral deer.

Goat farming should be tightly controlled, with heavy penalties.