Rabaul and its strategic military importance

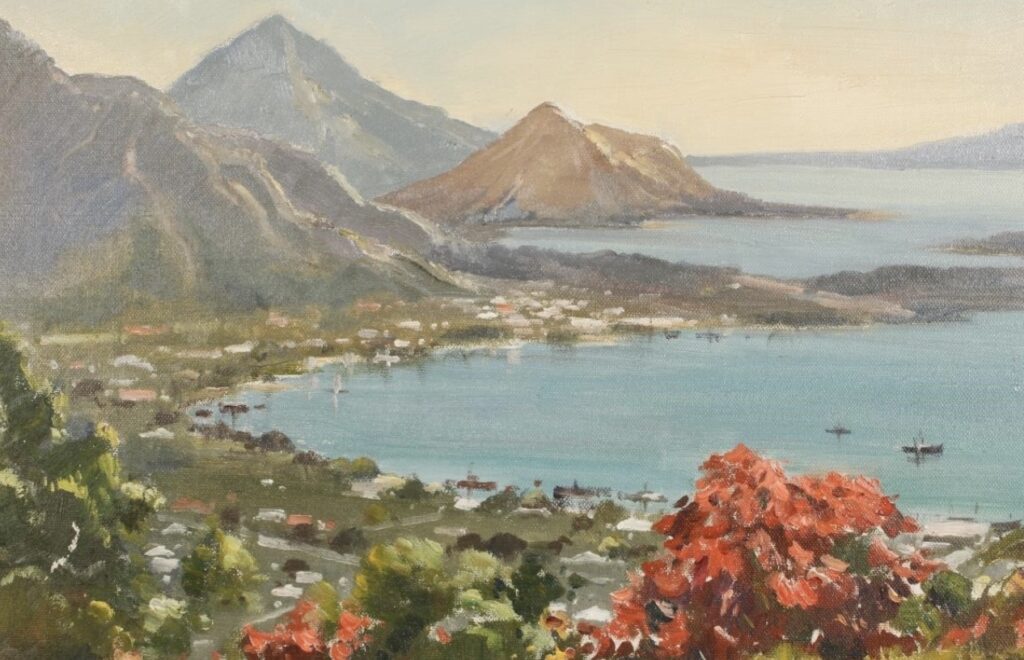

Rabaul, a town of striking beauty nestled on the north-eastern tip of New Britain in Papua New Guinea, boasts magnificent deep-water harbour encircled by a stunning volcanic flooded caldera three kilometres wide. This natural fortification, combined with its strategic location, made Rabaul a coveted prize for colonial powers and, eventually, a significant battleground in the Pacific theatre of World War II.

Rabaul’s colonial narrative began in 1884 when the Germans, eager to expand their empire, claimed the New Guinea islands. They transformed Rabaul into a sophisticated modern town adorned with elegant colonial structures – broad, tree-lined avenues, ornate buildings, a tramway, and parks and gardens with bougainvillaea blooms in red, pink, yellow and white. They also built a strategically placed wireless station near Bitapaka.

After the outbreak of World War I, an Australian expeditionary force of 1,500 men was dispatched to capture Rabaul and occupy German New Guinea. It was the first-ever force to leave Australia, using its own ships, under the command of Australian officers. In the battle that ensued, Able Seaman W. G. V. Williams was the first Australian to die in action in that war.

After the war in 1920, as the victors were carving up a new global order, Australia was granted a mandate over the Territory of New Guinea, converting Rabaul into an administrative centre and idyllic British outpost:

“an inviolate enclave of the British Empire”.

During the inter-war years, Rabaul and its residents enjoyed an idyllic lifestyle and prospered. Many Australians, mainly ex-servicemen, went to the islands to carve out a new beginning, taking over the German plantations and assets.

By the late 1930s, the population was 5,000, including 800 Europeans, 1,000 Asians and 3,000 indigenous workers employed as police, in government and as labourers and servants.

The Gathering Storm

In the heady and diplomatic years in Europe just before the outbreak of World War II, European leaders claimed that Hitler might be appeased in his grand ambitions if there was a return of former German colonies. On a visit to Rabaul on 1 July 1937, former Prime Minister William “Billy” Hughes told an audience that New Guinea was Australia’s and “all hell is not going to take it away”.

But it wasn’t the Germans the Australians had to fear. It was another enemy much closer to our shores.

The Nashin-Ron doctrine – a prelude to invasion

The 1930s heralded an era of heightened tension as Japan’s imperial ambitions became evident to strengthen its ambitions to rule the rest of Asia. The Nashin-Ron doctrine, advocating for southward extension, led Japan to invade Manchuria in 1931, and subsequently through South-East Asian territories.

If a broad-scale war broke out, the Japanese Imperial Navy, aware of its inferiority against the US, devised plans to weaken the US Pacific naval fleet before engaging in any battles.

The Japanese established a naval and military presence on Truk Atoll in the Caroline Islands just south of Guam and 1,100 kilometres north of Rabaul. It was their limit of interest, but the deep-water port of Rabaul represented a threat to their ambitions.

In February 1941, the Japanese Ambassador to the USA told the Secretary of State that a prerequisite for peace in the Pacific and South-East Asia required a recognition that Japan was the military power in the region.

In response, the USA pressured the Australian government to put a garrison at Rabaul so they could establish a major US Naval Fleet if required in the future.

Successive Australian governments failed to make firm decisions for shoring up their defences in South-East Asia. They firmly believed British forces in Hong Kong and the “impregnable” fortress of Singapore were enough to deal with any Japanese aggression. There was also a belief that no eastern nation would ever contemplate attacking a western nation’s military garrison. A nurse stationed in Rabaul said:

“…the popular belief held at the time was that Japan was a poor nation full of myopic little men who could not fire a rifle”.

In September 1941, Japan invaded Indochina (now Vietnam). In retaliation, the Allies froze Japan’s assets and imposed an oil embargo. The Australian military leaders hastily devised a military response called “The Malay Barrier”. They decided to allocate two brigades of the AIF 8th Division – one to Malaya, and the other was split into three battalion-sized garrison forces to protect the northern approaches to Australia and airfields linked with South-East Asia.

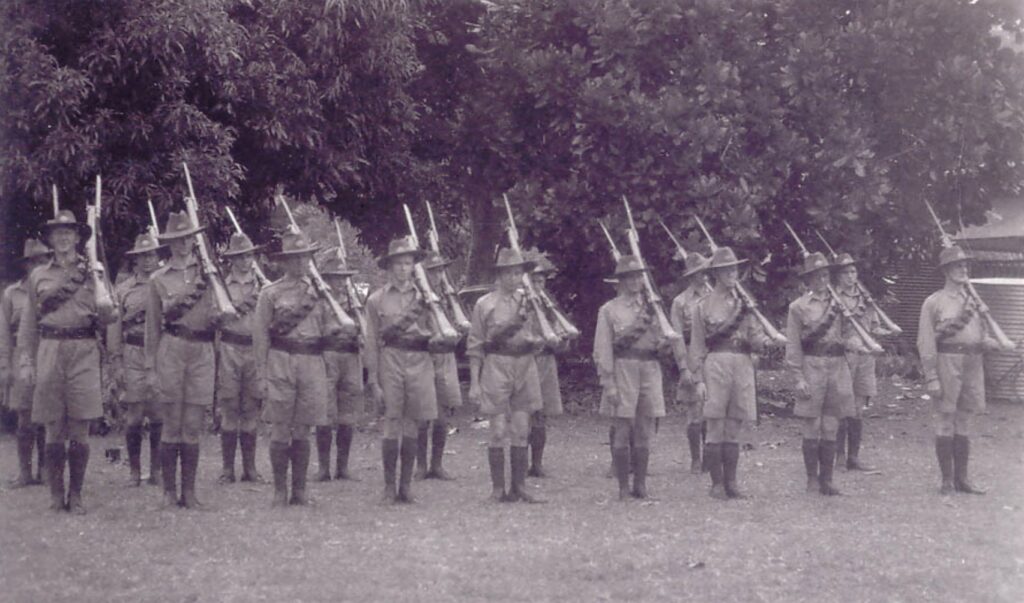

Despite having to observe the requirements of the League of Nations by refraining from making any defence preparations outside of war, when war was declared in Europe, the Australian Army made plans to install a screen of Coast Watchers in the Pacific Islands to warn of “hostile sea and air incursions”. They also ordered the raising of an unpaid militia force in Rabaul.

The response was overwhelming. There was little difficulty finding recruits between September 1939 and July 1940, leading to the formation of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (NGVR). While they initially had a force of over 400 men, many left for Australia to enlist for military service when WWII began.

After the recruitment drive, military authorities sent Sparrow Force to Timor, Gull Force to Ambon Island in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and Lark Force to New Britain and New Ireland in New Guinea, based at Rabaul.

By December 1941, the NGRV numbers were down to 80, but their wartime experience and standard of marksmanship were high, and their local knowledge of people and terrain proved invaluable. They saved the lives of hundreds of Australian troops and could have done more if the commanders utilised their skills more widely to better use.

The small force of poorly armed young militia

As the military intentions of the Japanese Imperial Force became apparent to the Australian government in early 1941, they advertised a recruitment drive. Men and boys as young as 16 gleefully signed upon a promise they would become members of the legendary AIF, thinking they would head to the deserts of the Middle East after reading newspaper editorials that made soldering sound noble and adventurous. They wanted to help their brothers and mates in the Middle East who were “covering themselves with glory”.

Regardless of the enthusiasm of the volunteers, the military bureaucracy and government were stifled by indecision and a lack of preparation in defending Australia and its nearby territories and allies from the threat of a Japanese invasion. Until then, they had focused on Australia’s war effort in Europe, helping the Allies by sending troops to Europe and the Middle East.

The Japanese, however, forced the Australian government’s hand.

Once signed up, the recruits were told they were too young to become ANZACS. Instead, they became militiamen and members of the Coast Defence Guard.

With little to no training on home soil, these militiamen left on the ship SS Zealander and arrived in Rabaul in April 1941. Disembarking, the troops found they were in a tropical jungle, not a sandy desert.

For the 1,400 men and six female nurses in Lark Force, Rabaul was a stunning tropical paradise. Blanche Bay had beautiful blue waters and numerous coral atolls. Simpson Harbour hosted the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) fleet. But they weren’t there for a holiday.

The skeletal garrison had a massive task to become a fighting force. The inhospitable geography of New Britain and New Ireland were well known. The 1,600-kilometre-plus coastline was formidable. They were also expected to protect two airfields and the seaplane base at Sulphur Creek.

Lark Force, however, wasn’t well equipped or strong enough in numbers to repel an invasion. There was no sea support, poor air support and little artillery. Nor were they well commanded.

Colonel John Scanlan served World War I with distinction, landing in Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 with the 7thBattalion, taking a bullet in his chest while advancing, recuperating and then fighting in the battles of Amiens, Mont Saint-Quentin and St Quentin Canal in France.

He arrived at Rabaul in October 1941, a man in stark contrast to the softer personality of the officer he replaced as commander, Lieutenant Colonel Howard Carr.

Scanlan was an aloof man who knew all he could do was work with what he had at his disposal. He based the defence of Rabaul on the assumption of the availability of a brigade group that never eventuated. That is why he made no plans for retreat or withdrawal.

Their artillery was two 6-inch World War I coast guns taken from Fort Wallace near Newcastle in New South Wales, which they had yet to fire. They were obsolete and antiquated equipment.

The artillerymen had to unload the guns and move them eight miles to install them, building roads and equipment to move the eight tons of guns. They then had to build a command post, accommodation, concrete emplacements, and trenches.

Anti-aircraft and anti-military landing craft batteries were primarily set up in poor locations. Lieutenant David Selby’s battery was positioned high on an elevated site of North Daughter, christened Frisbee Ridge. It gave great panoramic views but was silhouetted against the northern and southern skylines, compromising the gun’s position. They were also conspicuous from the land, sea and air.

As the young adolescent men waited for an attack, they became increasingly bored and irritable, and their experienced commanders knew they were not battle-ready.

Living inside the rim of a vast volcano in the equatorial heat meant an incessant south-easterly blew clouds of black pumice dust and sulphur fumes from nearby Matupi Crater. Throats and eyes were irritated. Twice daily, gun firing mechanisms had to be dismantled, cleaned of invasive grit, re-oiled and re-assembled. Waiting and sweating under the daily monotony of gun drills took its toll. They were not even allowed to let off a few practice rounds into the sky, as ammunition supplies were limited, and guns were faulty.

If they didn’t realise when they arrived, Lark Force soon learnt they had an almighty task to repel any Japanese aggression, and that became obvious between January and July the following year when the pitiful garrison at Rabaul turned into a tragic and terrifying place.

Prelude to invasion

The ignorance, complacency, and scandalously incorrect ideas about the fighting abilities of the Japanese nation forced the Australian government and armed forces command to rapidly reassess their thinking of the Japanese military strength and ambitions when, on the morning of 7 December 1941, hundreds of Japanese fighter planes attacked the USA Navy base at Pearl Harbour, Hawaii. It was a surprise attack that exposed just how ill-prepared the Americans were. The Japanese sunk or beached 12 ships, destroyed 160 aircraft and damaged 150, and killed more than 2,300 Americans and wounded another 1,000.

The Japanese also carried out simultaneous attacks on Hong Kong, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore and Malaya. By mid-January 1942, the Malay Barrier had crumpled to the Japanese, and they continued onto other islands, including New Britain and Rabaul.

In early December 1941, a Coast Watcher notified Rabaul of significant Japanese activity. The report was passed on to the Commander-in-Chief in Hong Kong. He replied,

“Your signal. I am not concerned”.

On 8 December, the Japanese fought with British and Commonwealth troops on the Kowloon Peninsular close to Hong Kong and destroyed a few British aircraft. The British forces had to retreat to Hong Kong a few days later.

When the Commander-in-Chief ignored calls for surrender, the Japanese artillery and aircraft started an intense campaign of bombing on 15 December and five days later, they controlled half of the island. On 24 December, the unconcerned governor of Hong Kong had to surrender ignominiously.

In September 1941, the Australian War Cabinet approved a proposal from the USA to transform the Rabaul harbour into a naval fleet for American ships. However, on 12 December, the Australian Ambassador told the Australian government the promised US fortification of Rabaul was extremely unlikely.

It was too late to bolster the garrison. With a real threat imminent, Australia’s War Cabinet decided that day to compulsorily evacuate Australian women and children from Rabaul and New Ireland. Males over 16 were to remain with their fathers. The relaxed lifestyle ended abruptly.

Evacuation orders were broadcast over Rabaul radio on December 16, 18 and 20. The evacuees boarded MV Neptuna and Macdhui on the evening of 21 December as heavy rain fell.

The government gave no reasons for not evacuating non-European women and children.

The remaining European civilians were government officers, planters, businessmen, traders and missionaries. Many were World War I veterans.

On New Year’s Day, as the troops held a sombre celebration, Scanlan messaged the troops:

“There shall be no faint hearts, no thoughts of surrender, every man shall die in his pit”,

and ended with the words capitalised and underlined,

“THERE SHALL BE NO WITHDRAWAL”.

Selby later learnt the order came directly from Australia.

The fall of Rabaul

On 4 January 1942, the tranquility of Rabaul was shattered as the first Japanese bombs rained down, marking the beginning of a relentless siege. Twelve local people died.

Twenty-two Zero bombers arrived in arrowhead formation and released their bombs over Lukanai airfield and the adjacent hospital. The aerial bombing continued for three weeks.

On 8 January, the last evacuation took place on MV Malaita.

In the first two weeks of December 1941, the RAAF 24 Squadron arrived at Rabaul to provide aerial defence for New Britain. First, four Hudsons arrived and then ten Wirraways and 130 staff. The Wirraway was a training and general-purpose military aircraft that was slow and required gunners to operate the machine guns in the rear cockpit.

The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero was a long-range, pilot-only fighter aircraft with a top speed of around 287 knots. They were armed with two 20mm cannons, two .303 machine guns and two 66-pound or 130-pound bombs.

The Japanese bombs were nicknamed daisy cutters. They were packed with assorted shrapnel of nails, razor blades, and bottle tops from Australian beers.

A further bombing raid occurred on 7 January, where 18 twin-engine bombers dropped 78 bombs on the Vunakanau airfield, about 11 miles south of Rabaul, while the Hudsons were being serviced and refuelled. One was destroyed, and the other two were damaged, as well as a Wirraway.

On 9 January, a Hudson carried out a reconnaissance flight, and the crew saw a massive concentration of aircraft and shipping at the Truk Islands.

On 20 January, the sky above New Britain was full of Japanese carrier-based aircraft – 40 fighters and 80 bombers. They attacked in relentless waves. Coast Watchers sent an early warning, but the message never got to the artillerymen.

The obsolete Wirraway aircraft were deployed, but the air battle was one-sided. It only lasted ten minutes. The Artillerymen witnessed a horrific scene in the skies above Rabaul. The RAAF planes and crews disintegrated in flames as Japanese Zeros shot them down. Lieutenant Peter Fisher described the scene:

“Fierce dogfight…the horror of the scene, made the more real when two minutes later the first Wirraway went spiralling into the sea, smoke and flames pouring from its engine and breaking up as it fell. Five Wirraways were lost in a matter of minutes”.

Upon hearing of the Japanese invasion of Rabaul, the Australian Air Board ordered Wing Commander John Lerew to attack the approaching Japanese convoy with “all available aircraft”. When he received the message, Lerew had just one lone medium bomber. He returned a message to his superiors:

“Nos morituri te saluitamus” “We who are about to die salute you”.

The Australian artillery batteries opened fire on the Japanese bombers. While they knew they had hit one, there were still another 80 left to bomb. After bombing the two airfields, the bombers attacked the ships sitting idle in the harbour, including the Norwegian freighter MV Herstein, which was full of copra. It had arrived on 14 January carrying 2,000 bombs for Lerew’s almost non-existent bomber force.

Harold Page, the deputy administrator still at Rabaul, cabled Canberra for permission to evacuate the remaining 300 European civilians in Rabaul. He was astonished at the reply he received,

“No one is to take the place of the copra aboard the Herstein”.

A decision to deny civilians to escape on a freighter a week before the invasion will forever be a stain on the government’s handling of the garrison at Rabaul.

Rabaul had a reprieve on 21 January because 60 Japanese aircraft bombed Kavieng in New Ireland. They attacked the airfield’s gun emplacements with much effect.

After sunset on 22 January, the air raid alarms sounded. The Japanese carrier-based dive bombers arrived en masse and deliberately kept well out of artillery range as they destroyed the Praed Point battery with devastating efficiency. As darkness descended and heavy rain fell, Selby was ordered to destroy the guns on Frisbee Ridge and return to headquarters.

The Japanese were ready to invade with the two coastal gun emplacements destroyed. Lark Force were sitting ducks.

Lerew was ordered to take the remaining Hudson to Port Moresby and assume control, and the remaining RAAF air and ground crew joined the Lark Force infantry. He ignored those orders and had already devised an evacuation plan, believing trained RAAF were more important elsewhere. The Hudson left with injured servicemen before dawn on 22 January and arrived at Townsville. The remaining RAAF men began to evacuate that day. Lerew organised Catalina aircraft at pre-determined places. Only three RAAF personnel failed to escape from Rabaul.

Chaos and retreat

Confusion reigned as last-minute defence plans – or the last stand – were implemented. To avoid troops being massacred by naval gunfire as the Japanese entered an undefended Simpson Harbour, they were sent to an improvised army headquarters at Raluana on the southern side of Blanche Bay. After months of preparing fixed defences, like Lakunai Airfield south of Rabaul, troops were withdrawn to beach positions on the other side of Simpson Harbour.

The same experienced carrier planes and troops that had attacked Pearl Harbour and taken Guam were in the Japanese invasion force. They left Guam on 16 January and arrived at Rabaul in the late afternoon of 22 January. There were 25 ships, including an aircraft carrier, five warships and 19 transports. What hope did the Australians have?

Between 3,000 and 4,000 Japanese troops stormed ashore at neighbouring New Ireland on 23 January. The 1st Independent Company had to retreat. The injured from the bomb attacks two days earlier were put on the barely seaworthy schooner Induna Star. It beached on a reef. The Australian commandos hid in the hinterland but, by 30 January, were fatigued and suffering from malaria, dysentery and skin diseases. That night, they boarded the Induna Star, moved to an inlet and hid. During the overcast evening and favourable wind, they sailed south. They were spotted and bombed by aircraft and couldn’t continue. The officers and wounded were taken onboard a Japanese boat, while the Induna Star was towed to Rabaul, and the remaining troops were put in captivity.

Scanlan and Carr realised it was pointless prolonging the fight against the enemy and decided all troops should withdraw. Scanlan infamously told Carr it was now,

“Every man for himself”,

epitomising the desperate situation. Carr passed on the message as best he could, but in reality, troops were already withdrawing to try to stay alive.

At Rabaul, the tiny, ill-prepared, inadequately equipped and poorly led garrison, forsaken by their government, faced an invasion force of 18,000 troops in the early hours of 23 January 1942. While the Australian forces held their positions as long as they could, many died. Without any support or a withdrawal plan, it was pandemonium as troops were ordered all over the place. No evacuation occurred. Instead, it was an uncoordinated escape into the surrounding jungles and mountains, looking for villages after the Japanese outflanked them.

Many stragglers were caught and massacred. On 3 and 4 February, 160 Australians were killed at the Tol and Waitavalo Plantations after surrendering. It is believed there were at least two other separate massacres of Australians in the early few weeks of February. A Court of Inquiry, held in May 1942 in Australia, concluded there were 144 Lark Force victims, but they did not include members of NGVR and civilians in their findings.

On 8 February, wracked with guilt after discovering the fate of men at Tol Plantation, Scanlan relieved himself of command and decided to surrender. Before the massacre, the Japanese sent him a note, “You will be responsible for the death of your men”. He left the Kalia Missionary, where Selby and his gunners were also staying, on the morning of the 9 February to surrender.

Selby wrote about Scanlan dressing up for his surrender:

“There was the Commandant in a blaze of glory complete with summer-weight uniform, collar and tie, red gorgets and a red cap band. He was wearing new boots and had cut his hair and shaved”.

His appearance was in stark contrast to the troops he commanded, who wore ragged shorts and shirts, battered boots and stubbly beards as they desperately tried to flee to freedom without food, very little water and suffering only malaria and dysentery if they were lucky. Those unlucky tried to stay alive after receiving significant wounds.

About 400 eluded the Japanese and managed to get to the south and north coasts of New Britain. A fleet of small boats organised by Australians on the New Guinea mainland took them to safety. However, other Australian soldiers and civilians surrendered. Over 1,100 spent five months in a prisoner camp at Rabaul. They were not treated well, deprived of food and medical supplies, and forced to work as labourers on the wharves.

Back in Australia, when the media made public the news of the invasion, the government was at pains to assure the public there was no fighting and “every possible step was being taken to safeguard Australian lives and property”.

A news blackout followed after politicians found themselves under siege by concerned families wanting to know the fate of their loved ones. On 6 February, Deputy Leader Frank Forde wrote to Prime Minister John Curtin:

“The attitudes of those with near relatives in our Garrison at Rabaul is becoming bitter and hostile at the lack of news of their sons, brothers and husbands, and of the feeling that is being created that although something could be done to assist them, nothing is being attempted”.

But as a trickle of escapees managed to reach New Guinea and Australia, suppressing their stories and the truth became impossible for the government.

There was one example of a treacherous escape attempt by a boatload of officers, NGVR, civilians and native police that eventually reached Cairns. Instead of a hero’s welcome, the escapee’s arrival did not overjoy the authorities. They forced the men to quarantine on their barely seaworthy and unsanitary boat, shave their beards and threw their few possessions overboard.

Military authorities organised the local Vicar to host the men at one of their schools and sleep on the floor. When the Vicar saw the condition of the men, he was highly embarrassed and believed military officials should have sent them to the best hotel in town. It wasn’t until the Red Cross arrived that they gave the escapees food and clothing.

The military bureaucrats were pathetically officious. They told one soldier he was guilty of dereliction of duty. Another received a bill for his uniform. Another soldier who lost his paybook was not allowed to access any money. One soldier had to send a telegram to his brother.

“Arrived at Cairns yesterday, broke please send a fiver, love Gordon”.

It was not until Gordon arrived in Sydney that they gave him clothes to replace the hospital pyjamas. He also received a bill for lost rifles and other gear!

While the media portrayed the official line of bravery against enormous odds, it hadn’t yet become part of the public conscience that the Japanese invasion and occupation of Rabaul was one of the worst chapters in Australia’s wartime history. And it was only about to become worse on 1 July 1942.

The MV Montevideo Maru

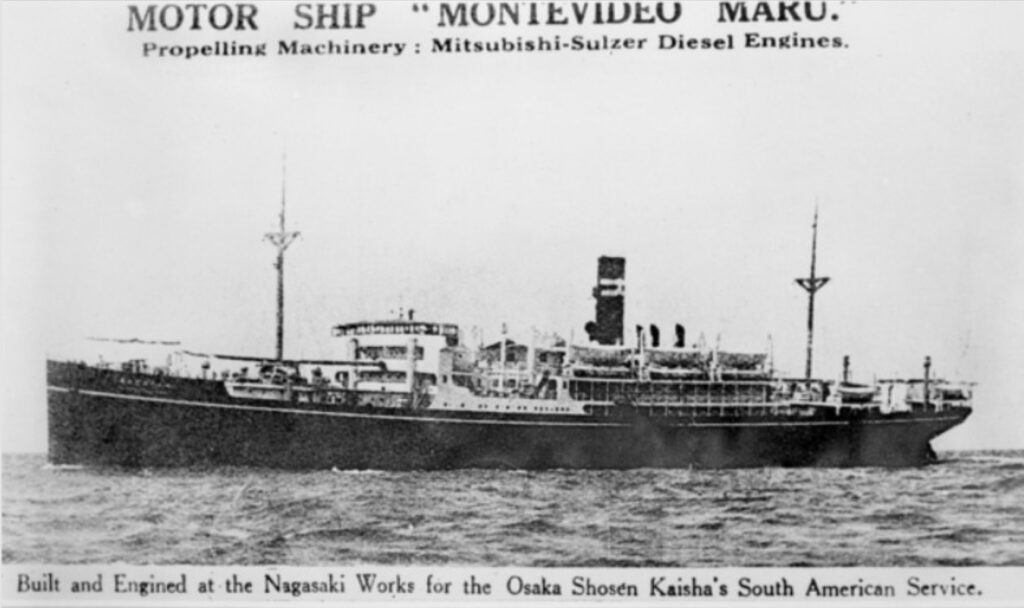

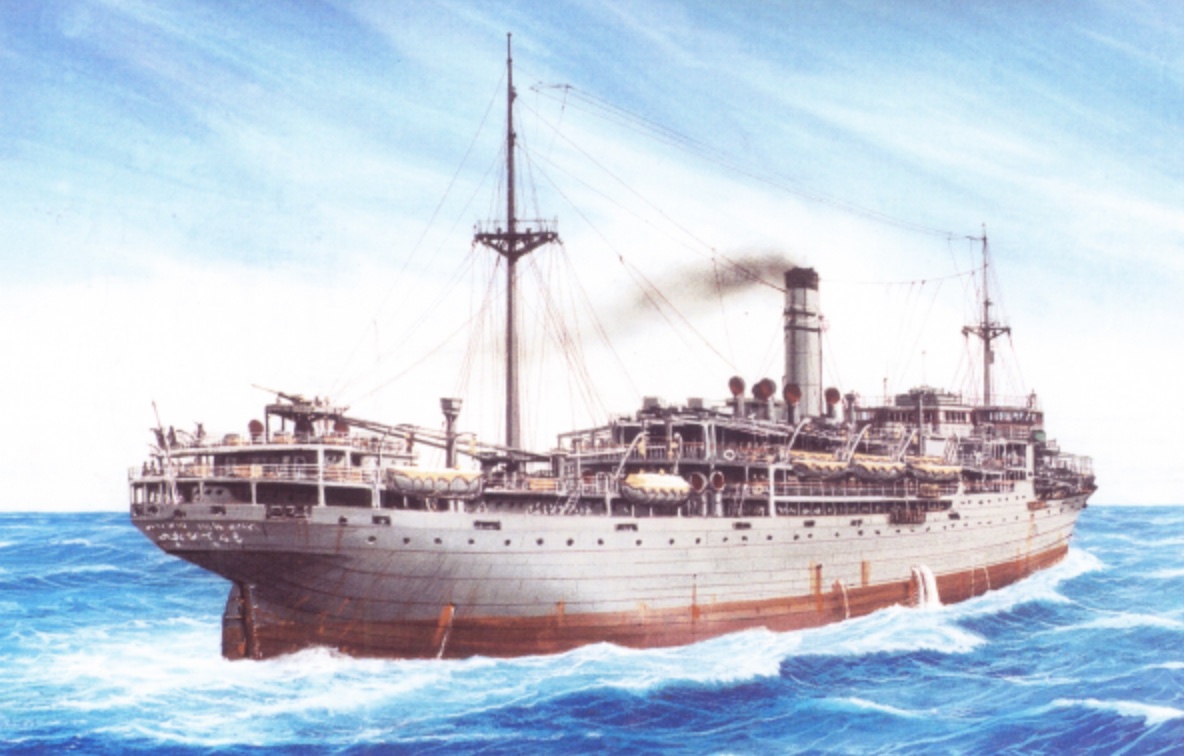

On 22 June 1942, the Japanese separated the officers in POW camps from the soldiers and civilians. The Japanese forced more than a thousand soldiers and civilians into squalid holds in the MV Montevideo Maru. The ship was a Japanese passenger vessel requisitioned by her Navy to transport troops and supplies during the war.

The ship was initially bound for Japan to drop its human cargo as slave labour, but it headed across the South China Sea towards Hainan. The ship carried no symbols to indicate it had human cargo.

The USA Salmon Class submarine USS Sturgeon had just received a refit at Fremantle before being sent to the waters west of the Philippines capital, Manila. On 25 June 1942, they sighted a nine-ship Japanese convoy. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander William “Bull” Wright, gave the order to torpedo the largest ship, which was successful. In return, they were subject to 21 depth charges and were fortunate to escape with minor damage.

The Sturgeon then took up patrol north-west of Bojeador in the Philippines. Early on the morning of 1 July, they observed a lone ship heading westwards at high speed after rounding the tip of the Philippines’ Luzon Island. The MV Montevideo Maru had been at sea for two weeks with the Rabaul prisoners. Sturgeon set up the chase but couldn’t get close enough until the ship finally slowed to wait for two destroyer escorts.

At 0225, Sturgeon fired four torpedoes, two of which fatally hit MV Montevideo Maru on the starboard quarter, tearing open the holds and exploding an oil tank. The ship’s officers ordered the crew and guards to abandon the ship, lowering three lifeboats onto the water. There was no attempt to release the POWS from the holds.

Of the 88 Japanese on board, 17 survived the sinking. None of the 208 civilian and 845 military POWS survived. It is Australia’s worst maritime disaster, exceeding the sinking of the HMAS Sydney and the hospital ship MV Centaur.

Did the Australian government abandon a garrison and its civilians?

As the Japanese ruthlessly and rapidly invaded and conquered strategic British and Australian military posts in South-East Asia, the Australian government was in shock, and all the politicians could do was argue among themselves about who was responsible for not taking the Japanese threat seriously.

In 1940-41, when Australia, particularly Rabaul, needed strong and united support, the Australian government lacked stability. Politicians had little care about the welfare of the troops they ordered overseas before, and in the early part, of the Pacific War.

1941 was not the best political year for Australia; it was marred by procrastination, poor decisions, and lost opportunities. The War Cabinet acted on military advice and diplomatic pressure, agreeing to garrison forces on outlying islands. One glaring example of the diplomatic pressure was the decision made on 15 December 1941, after the military Chiefs of Staff argued that evacuating troops from Rabaul was impossible because of the effect it “would have on the minds of the Dutch” in Dutch East Indies.

How could a tiny garrison, using antiquated equipment, be expected to defend 50 miles of perfect landing beaches from any invasion from a powerful enemy? These garrisons were under-armed island units with little air cover or naval support. Sadly, those in charge knew these garrisons could only offer “token resistance”.

Official RAAF historian Alan Stephens believed sending RAAF 24 Squadron and their obsolete aircraft to Rabaul was an “act of delinquency” on the part of the War Cabinet.

Kathryn Spurling, in her book Abandoned and Scarificed: The tragedy of the Montevideo Maru, exposed a secret army minute dated 2 August 1941, which admitted that,

“To secure Rabaul against attack would require a scale of defence beyond the resources at its disposal”.

So, it was apparent well before the Japanese invasions across South-East Asia that a small force at Rabaul could not be effective against the naval and military forces Japan had, yet the government still sent them there.

The government sacrificed troops of young militiamen and officers in the name of “duty”, and the best they could have hoped for was to inflict casualties on the Japanese before being casualties themselves.

Even worse is that the Australian government, military leaders, and bureaucracy abandoned the Lark Force for decades afterwards. They denied what occurred in Rabaul, denied any responsibility for their senseless sacrifice, and denied resolution for the families affected.

It is a sad fact that the fate of all the Rabaul prisoners-of-war may never, unequivocally, be determined and controversy will always accompany this disaster.

The NGVR was also frustrated by the “fatuous incompetence” of being ignored and not fully mobilised. Rabaul and the surrounding area were their home and livelihood, and they were uncomfortable that it faced total destruction. While they were voluntary unpaid officers equipped with antiquated weapons, their intelligence, skills, and local knowledge were valuable during this period.

While publicly, the Australian government argued they would never stand to have their men deserted, privately, they admitted its small garrison and its troops at Rabaul were “hostages to fortune”.

Lark Force was not helped by having an aloof commander who never questioned orders and refused to consider alternate options from his field officers. The troops became very uneasy when they realised that authorities had done nothing to arrange an evacuation once they got overwhelmed. Their early optimism, reflected in their casual, relaxed demeanour in a tropical paradise, soon changed to feelings of despair and anger.

The fall of Rabaul is a national shame. What to me is the most shameful part of the whole fiasco is the decades of obfuscation shown by the government and the military command around the fate of 1,053 people. It led to decades of misery and heartache for families of those lost.

For the families affected, they still do not know if their loved one died with the ship or was killed onshore by the Japanese as part of the invasion.

I mentioned the same thing with the sinking of HMAS Sydney.

I have left out many details about the fall of Rabaul. I recommend Kathryn Spurling’s book or even Harrison Christian’s Should we fall to ruin if you want to read some of the harrowing and desperate exploits of the Lark Force as they tried to survive in the aftermath of the invasion of the Japanese.

As a postscript to this story, the wreck of the Montevideo Maru was located at a depth of more than 4,000 metres off the coast of the Philippines in April 2023.

The wreck, sitting at a deeper depth than the Titanic, will not be disturbed. No artefacts or human remains will be removed. The site will be recorded for research purposes out of respect for all the families of those onboard who were lost.

Another great read Robert. I suspect our defense establishment is even worse prepared today than it was then and still obsessed with issues ephemeral to the actual protection of the nation.

Thanks,

Typical army – SNAFU!

Very close to home Robert. Lyn’s uncle Sgt Bruce Gilchrist was lost on the Montevideo Maru; he was in Lt David Selby’s AA team on Frisbee Ridge manning those faulty 3 inch AA guns. Much family heartache at the incompetency and intransigence of the military authorities on the ‘Rabaul incident’ right up to the end of the war. David Selby survived the war and his book Hell and High Fever (Currawong Publishing Sydney 1956) well worth the read.

A hard content read Robert.

Were any Japs hanged after for war crimes at Rabaul or indeed PNG? Carol’s dad, Ted Gormley (Australian Jungle Fighter, p30 Jungle Warfare), was shot and evacuated from behind enemy lines by Bougainville natives and afterwards he learned that two were beheaded for assisting him.

He never forgave the Japs and would not allow rice or any Jap stuff into 34 Red Hill Rd Gympie.

I don’t know about any retribution to the Japanese involved, but I doubt any were hanged. I recall as a kid that many WWII veterans involved in the Pacific War never forgave the Japanese.