When the railways of Queensland and New South Wales met in 1888, the border towns of Wallangarra and Jennings were created. It was the only rail link between Brisbane and Sydney, leading to a new era in transport. As a consequence, both states introduced the Intercolonial Express train service.

However, the two governments could not resolve the differences in the railway gauges between each state. Queensland’s “narrow” gauge was 3 feet 6 inches, and New South Wales’ “standard” gauge was 4 feet 8 inches. This ridiculous situation meant that passengers and freight had to leave the incoming train and move across the station platform to board the outgoing train to continue their journey.

Nor could they even agree on the design of the station building that straddled the border. The photo above shows the Jennings part of the building on the right, constructed with a skillion roof, whereas the Wallangarra side has a bull-nose roof.

The pandemic

A century ago, the world confronted what was claimed to be an influenza pandemic. It became known as the Spanish Flu not because it originated in Spain but because it was first widely reported there. About 500,000 million people, a third of the world’s population, were infected, and at least 50,000 million died, more than in World War I. In comparison, 15,000 Australians died, which was one of the lowest death rates from the disease.

Officially it was called a flu pandemic and started in 1918, during the last year of World War I and passed through soldiers in Western Europe in successively more virulent waves.

The Spanish Flu arrives in Australia

The Australian government set up its first line of defence to prevent the Spanish Flu from reaching the country. They implanted a maritime quarantine on 17 October 1918 after learning of outbreaks in New Zealand and South Africa.

The first infected ship to enter Australian waters was the Maratam from Singapore, arriving in Darwin on 18 October 1918. Over the next six months, authorities intercepted 323 ships, and over half carried the infection. Of the 81,510 people they checked, 1,102 were infected.

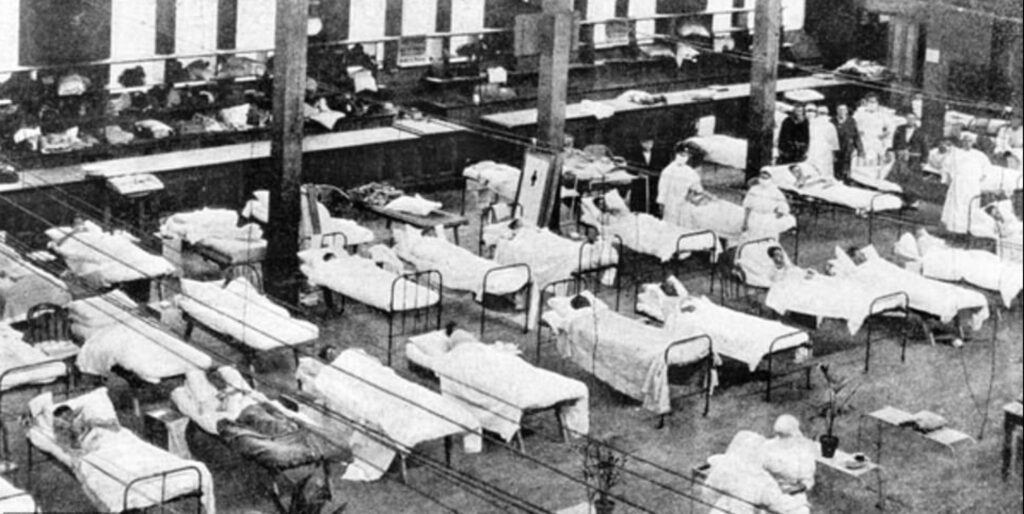

The government then adopted a second line of defence to contain any outbreaks in the country. The states agreed the federal government would take control. When the states proclaimed they were carrying the infection, they would arrange emergency hospitals, services and medical staff.

The maritime quarantine contained the spread of the disease until its virulence lessened. A single-entry point was suspected in Melbourne on 9 or 10 January 1919. There was initial confusion about whether the disease was the “Spanish flu” or a continuation of the seasonal flu virus from the previous winter.

The uncertainty delayed the confirmation of an outbreak, which allowed it to quickly spread to South Australia and New South Wales by the end of January 1919.

The pandemic exposed tensions in the new Federation, and the Commonwealth temporarily withdrew from its agreement with the states. Soon, each state made their own arrangements to handle outbreaks, including the imposition of border controls.

Quarantine Camps

Queensland was one of the last places in the world to host the “virus”. On 28 January 1919, authorities took the drastic step of suddenly closing the New South Wales and Queensland border to stop the spread of the deadly Spanish Flu, later called H1N1, into the northern state.

The Health Act gave authority for the Queensland Commissioner of Public Health to issue regulations for state intervention of a person’s civil right, such as mandatory examination, detention and isolation of anyone likely to have been infected or who had been in contact with anyone sick. The regulations gave the police the power to use reasonable force required to prevent any breach or to apprehend anyone suspected or had violated the public laws.

On 28 January 1919, the Police Commissioner instructed police to stop all persons crossing into Queensland from New South Wales. He sent additional officers to the border towns of Coolangatta and Wallangarra. At Coolangatta, 11 extra police officers arrived with 2 Bell tents, 22 brown blankets, 11 bush rugs, waterproof sheets, pillows slips, and bed covers for their accommodation.

The Queensland Government Gazette announced on 6 February 2019:

“No person shall enter the State of Queensland from an infected area … If any person enters Queensland, except in the manner prescribed by the Regulation, he shall, in addition to any other penalty to which he may be liable, pay the whole cost of his isolation”.

The aim was to try and prevent the spread of the “threatened visitation of pneumonic influenza to Queensland”.

The restrictions meant people from infected areas, essentially those travelling from New South Wales, had to quarantine. The government set up camps to accommodate people while they quarantined. The claimed primary purpose of the camps was to get Queenslanders back to Queensland safely. Entry to the camp was via a pre-applied permit through the Queensland Tourist Bureau in Sydney.

However, to those affected, it didn’t seem that way. Not only were the camps bursting at the seams with people desperate to get home but at the peak of the “influenza” outbreak, there were over 700 people on the waitlist to access the Wallangarra camp.

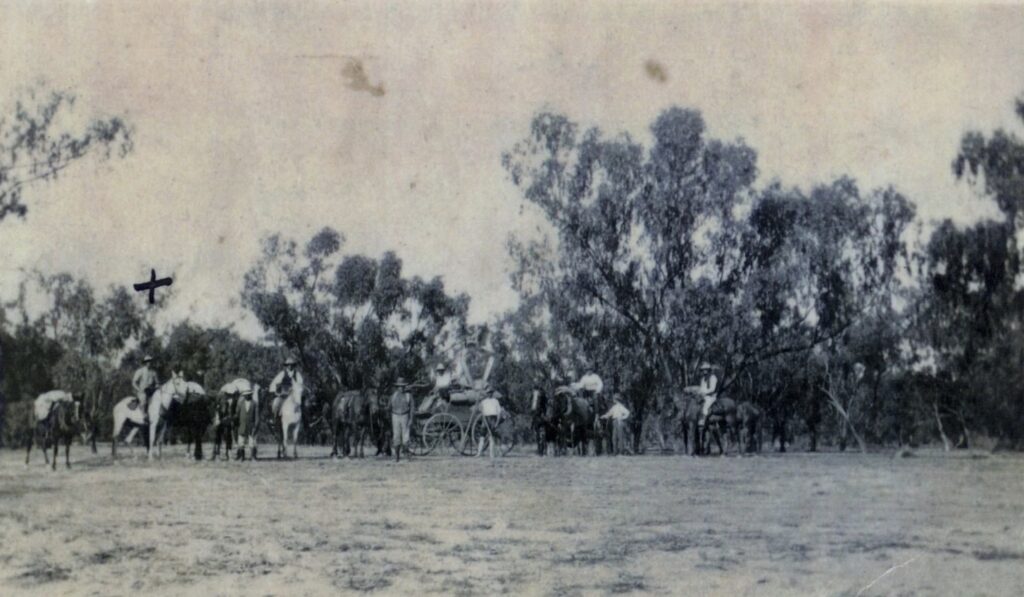

Initially, Coolangatta, Wallangarra and Goondiwindi were the only towns with dedicated border crossing points. The decision to only have three entry points led to significant applications for exemptions. Under relenting pressure, the government established medical screening posts to allow bona fide Queenslanders to return to the state via Wompah, Hungerford, Wooroorooka, Adelaide Gate and Mungindi. Border patrols also operated at Killarney, Stanthorpe, Texas and Hebel.

The constable stationed at Adelaide Gate in the Charleville Police District was provided three camels by the manager of the nearby Nockatunga Station. The camels were his only means of patrolling the border through the Western Desert Country. He had to employ an Aboriginal stockman from the station to help handle the camels. Elsewhere in the Charleville district, border patrol officers used Howard-brand bicycles.

Many people tried to break the quarantine requirements by crossing the border by train, car, boat or on foot. Police tracked most of them down, penalised them, and placed them into quarantine. One example was a group of men, one of whom was a railway employee, who left Tenterfield on foot, crossed the border into Queensland and flagged down a train using a railway issue red flag. They were returning home to Toowoomba after taking part in a shooting competition.

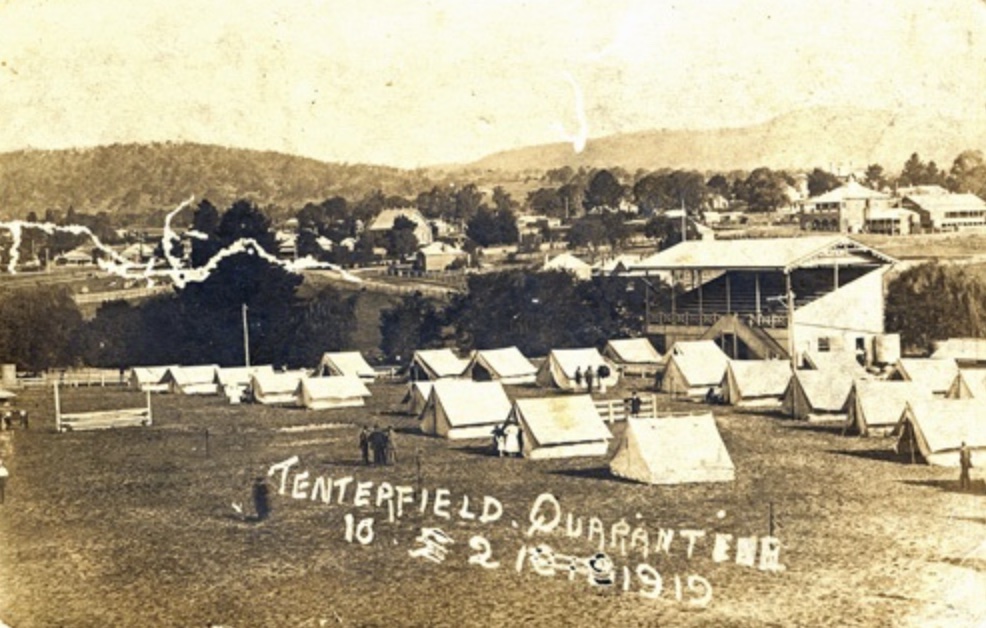

The Tenterfield arrangements

On 28 January 1919, passengers travelling north on the Brisbane Express arrived at Glen Innes. A smiling railway official told them they were quarantined, saying they:

“Should stay here. You’ll get no accommodation in Tenterfield”.

Little did they know they were part of the broader ongoing struggles between state governments and the Commonwealth government with the Commonwealth arguing over what was to be done with the stranded passengers and, more importantly, who would pay. No one gave them information on how they would return to Queensland, so many decided to try their fate at Tenterfield, closer to the border and the last stop during the pandemic. However, finding a lack of accommodation, they rechristened the town as “tent-or-field”, as that was their only option.

The residents of Tenterfield strongly objected to the sudden influx of people overwhelming the town as it was the last decent settlement before the border on the rail line.

Things boiled over when the medical officer was sent from Brisbane to lay down decrees sent from the marbled buildings on George Street. He gradually realised the situation was not as the government led him to believe. He found the camp he was to command didn’t exist. He was also alarmed to discover every available billet in town was crammed with hundreds of people. Meeting with the councillors, he demanded choices regarding setting up a quarantine station. The reply he got:

“We fear we have none other than accepting the burden that rightly should be borne by the Queensland Government”.

He was given two options at either the gymnasium or the school, both of which were unsuitable. The only suitable spot favourable to the doctor was the showgrounds. The show committee only granted its use for not more than two weeks. However, it was quickly overrun with the Queenslanders trying to return home. The townsfolk passed a motion at a public meeting that a quarantine camp should be located closer to the border, away from women and children, and not intrude on their town.

The medical officer and Councillors inspected Sunnyside and Wallangarra (Jennings) on the border. While Wallangarra was feasible, the medical officer was concerned that making a habitable camp would take at least a week and preferred the Tenterfield Showgrounds until then.

They set up a camp in Tenterfield until authorities sorted other arrangements elsewhere. On Friday, 7 February 1919, the medical officer prepared a plan for the camp and arrangements made with a local contractor to build latrines, kitchens and other buildings. Workers and volunteers started early on Saturday morning, and the camp was ready for occupation by midday on Monday using volunteer labour. An urgent cable was sent to Sydney requesting bedding for at least 450 people. The peak numbers at the showgrounds were around 500.

Locals installed an inhalation chamber a week later. Medics put camp residents through the chamber twice on Saturday and once the next day.

They divided the camp into four compounds –single women, married couples with children, and two for single men. It was done in case the “pneumonia virus” reached the camp, and the inmates at the other three compounds were free to leave at the end of their quarantine. The government charged each adult £2-10 and children half that for the six days the camp ran.

The camp closed on Monday, 17 February 1919 and shifted to Wallangarra.

Those who couldn’t or wouldn’t pay were forced to sign, under protest, an undertaking they would pay their expenses within three months. Many people refused to sign the undertaking, including Mr William Riordon, MLC from Brisbane, who was a trade union organiser serving as the branch president of the Queensland Australian Workers’ Union and later served as a judge at the Queensland Industrial Court.

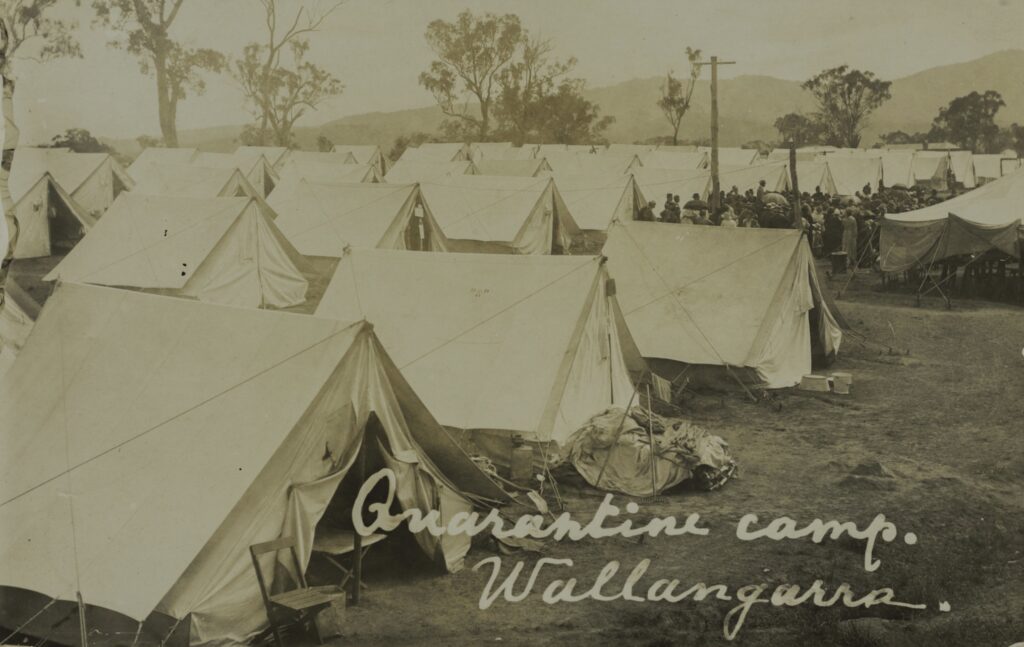

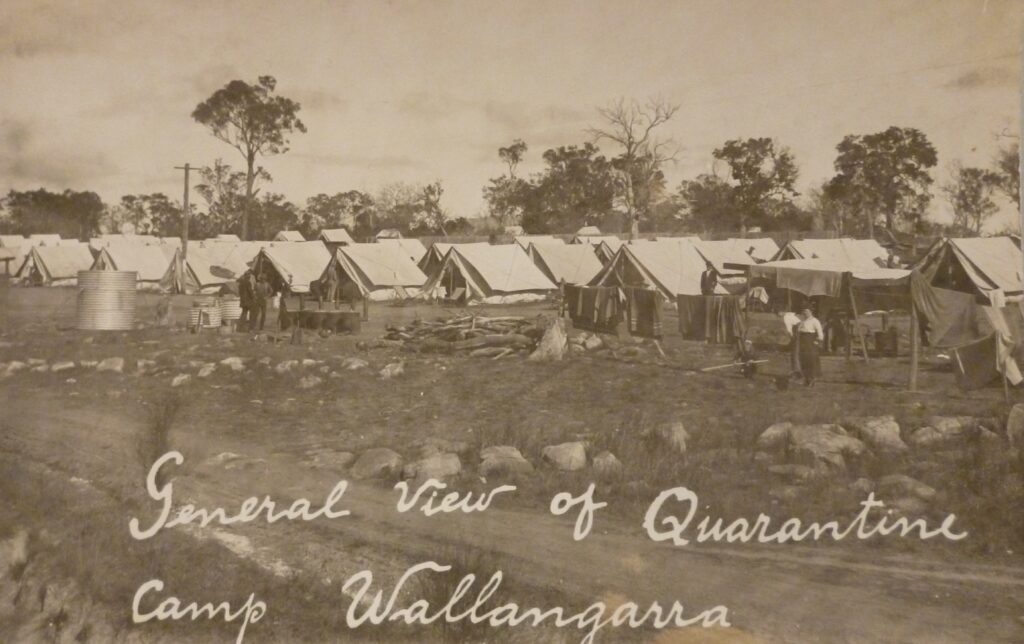

The Wallangarra Quarantine Camp

Wallangarra was a relatively new town, divided by the border that grew to service the railway that ran between Sydney and Brisbane. It became an essential and busy hub on the border, essentially a “break of gauge” transfer station. On arrival, every passenger had to change trains. Every bale of wool, every bag of mail was moved from one train to the other. Even circuses had to upload and reload.

The town became one of the quarantine camps as part of border control restrictions. While built in New South Wales, on the western side of the railway yards and its perimeter patrolled by New South Wales policemen, the Queensland government controlled it.

The camp was set up on 15 February 1919. Over 300 hundred people were in Tenterfield waiting to arrive at the camp once it opened. A further 150 were stranded in Tenterfield, unable to enter the quarantine station set up at the Showgrounds. The camp operators requested the New South Wales government not allow anyone to leave Sydney for Queensland until the quarantine camp was operational.

After the ten-mile rail journey from Tenterfield, the Ipswich City Band and soldiers greeted the new arrivals in Wallangarra to lift their spirits while they settled into their tents. No one representing the Queensland government was there to welcome them. Organisers arranged the white tents in orderly rows on the western side of the railway station. There were no trees in the campsite, so the “prisoners” followed the shadows thrown by the roomy tents for shade.

Authorities kept people entering the state in the quarantine camp for seven days. The camp was far from 4- or 5-star accommodation – just quickly erected camps of canvas tents. And just like the recent Covid quarantines, people paid for the privilege. It cost 7/6d per day for a single person (equivalent to $35.23 today) to stay at the camp. Not bad for a canvas tent with shared ablutions and two meals a day! The imposition of paying for their forced incarceration was the single biggest complaint.

Medical staff required camp residents to be inoculated, attend the specially constructed inhalation chamber three times a day for ten minutes, breathe in zinc sulphate fumes, and pass a medical check at the end of four days.

On 23 February, 162 people, including children, arrived by train from New South Wales and eight arrived by car. The registers show more than one compound, each containing up to 12 camps.

As expected, the camp didn’t run smoothly at the start. A police report described the camp as “a farce”. The quarantine guards, who were returned soldiers, worked in the camp, as did other working staff, and were in constant contact with each other and the public of Wallangarra. Someone alleged the Health Inspector visited the camp but stayed at the hotel in town.

There were many complaints about the less-than-ideal conditions at the camp due to the haste in which they set it up. Businessman Henry Sykes wrote to the Under Secretary:

“During quarantine, our tent was, to our knowledge, never once examined. The sanitary arrangements were simply shameful. We never had any cow’s milk; as I said before, we waited on ourselves and 90 others. For all this pleasure, we paid our Government … We were examined for temperature daily, inoculated twice and compelled to go through the inhalation chamber three times. Nine of our totals were detained on account of temperatures. No one seemed sorry to leave the compound, but we all look back on our quarantine as an experience as soldiers look back on the war.”

In early March 1919, the quarantine station at Coolangatta was closed, and the only way to enter Queensland from the south was via Wallangarra Quarantine Camp.

Border closures impact business and cross-border trade. Graziers could not move their cattle into Queensland to “prevent them from starving”. The storekeeper in Texas wrote to the Home Secretary saying he had a load of flour detained at the border and was seeking to take delivery. The response via telegram allowed someone to pick up the flour, but no one from New South Wales could cross the border.

Of the 5,321 people who passed through the quarantine camps into Queensland, no one was diagnosed with the Spanish Flu.

In early May, the “virus” finally crossed into Queensland, and soon after, the government re-opened the borders and the canvas tent town at Wallangarra was quietly dismantled.

The Queensland government’s determination to close its borders, however, didn’t save the state from suffering a mortality rate from the Spanish Flu the same as the other states.

A Final Word

There are a number of factors that make this “pandemic” interesting. Firstly, it wasn’t flu related as the disease was bacterial even though, at the time, the major focus was on stopping the spread of a virus.

Secondly, and what makes the whole experience intriguing, is that microbes that so suddenly wiped out most of the casualties were fit, young men. Epidemiologist Karen Starko has postulated that the real culprit was one of the most frequently prescribed drugs in modern medicine: aspirin. Not necessarily a cause of the initial sickness, but dispensing high doses of aspirin is now known to be highly toxic, and leads to a dangerous build up of fluid in the lungs which contributed to the incidence and severity of symptoms, bacterial infections, and mortality experienced by the ailing soldiers.

Aspirin was first synthesised just before World War I as a “wonder drug”. Initially it was presented as a panacea in the same way that Covid vaccines are regarded today.

When the aspirin patent expired in 1917, Bayer launched a major marketing campaign extolling the virtues of its “pure” product. In the early autumn of 1918, as the German offensive was sweeping across the Allied lines, a severe respiratory disease was killing American recruits.

This drew more attention to the drug as vast supplies were purchased for prophylactic use to the millions of men sent to fight the Germans.

In 1918, physicians did not fully understand either the dosing or pharmacology of aspirin, yet they were willing to recommend it. Its use was promoted by the drug industry, endorsed by doctors wanting to “do something,” and accepted by families and institutions desperate for hope.

Starko’s explanation is that high doses of aspirin shattered their immune systems. The spread of buccal and nasal bacteria to the lungs, unchecked by bodily immunity, caused a respiratory crisis.

Medical authorities at the time recommended large doses of aspirin of up to 30 grams per day. Today, about four grams would be considered the maximum safe daily dose. Large doses of aspirin can lead to many of the pandemic’s symptoms, including bleeding.

Interestingly, shortly after leaving New York at the end of September 1918 enroute to Europe, many soldiers were already sick and the decks of the US troop ship Leviathan were covered in:

“pools of blood from severe nasal haemorrhages.”

Nurses from Australia also dispensed aspirin in tablets to ailing military men, reducing aches and fevers in a bid to allow the body to strengthen its natural defences.

Whatever the cause, the “virus” spread rapidly worldwide as soldiers returned from active service at the war’s end.

The other equally intriguing aspect is that the pandemic was the catalyst for the rise of the pharmaceutical industry, facilitated by the allopathic (non-traditional) model of medicine.

The Flexner Report, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and published in 1910, transformed medical training and practice in America. One of its legacies was to prioritise patented petrochemical synthesised drugs over natural remedies and a healthy lifestyle.

Modern medicine is a billion dollar industry raising the prospect of controlling society by controlling health. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), citizens took a daily dose of the comforting “Soma”, trapping them in a state of dependence. Today, one in six adults take “happy pills” (antidepressants) with no therapeutic benefit other than biochemical maintenance.

Interesting comments about the aspirin taking and results. Thankyou Robert.