“Bellingen continues to attract younger people with what they perceive as Bellingen’s ‘hippy’ and ‘alternative’ reputation, with love and peace in their hearts and wellness and wokeness in their souls. Paul Hemphill

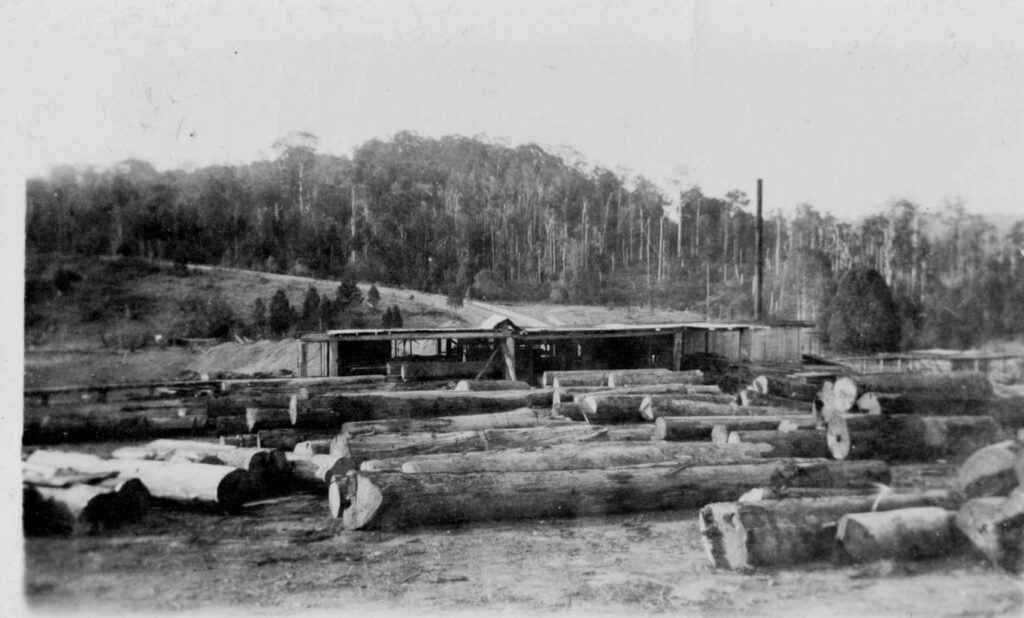

The Bellinger Valley has a long history of dairy farming and timber harvesting.

The devastating floods of the 1950s played a major role in the eventual decline of the dairy industry. Farmers couldn’t get their cream to the butter factory. Roads through the valley were blocked, bridges were washed away, and the Bellingen Council couldn’t compete with other councils for the limited supply of road repair materials. Timber to repair the bridges was also difficult to obtain.

A change to the Dairy Act in 1970 forced dairy farmers to supply fresh milk instead of cream to the butter factories. This immediately forced out all the small holdings with 50 or fewer cows that had previously supported families through cream cheques, pig sales and self-sufficient farming. They couldn’t afford the modernisation of milking machines and refrigerated vats. Plus they lived in areas that didn’t have all weather road access for large milk trucks. Consequently, most farmers sold their land cheaply or simply walked away.

Then, long before it was fashionable, the newcomers invaded.

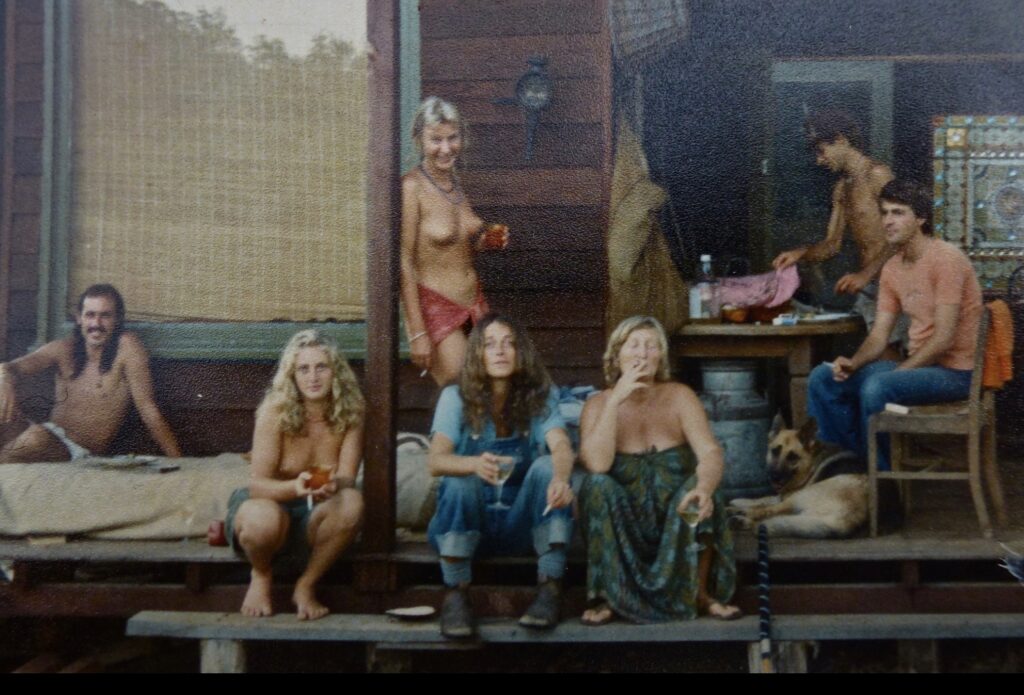

The hippys started to arrive after dairy farmers willingly sold to the newcomers as their families didn’t want to carry on the traditional farming lifestyle.

The new arrivals were predominantly city-bred young folk seeking an alternate lifestyle. They rented empty houses on old dairy farms at Darkwood, the upper reaches of the Kalang River and the Promised Land.

Most didn’t have jobs and were on the dole. The dole allowed for a youthful migration into rural Australia, leading to thousands of young Australians invading the countryside.

The influx of hippys and the decline of dairying created interesting times for the Bellinger Valley. The land could no longer support smaller dairy farmers because of the industrialisation of the dairy industry, the oil crisis, inflation and the incompetent Whitlam government. By decade’s end, the new settlers had transformed these farms to live close to nature.

They bought the relatively cheap land and established what was colloquially called “communes” but officially designated as “multiple occupancies” where families and friends formed co-operatives, bought land “in common”, and built their own homes.

I arrived on the scene at the end of 1990. Though I didn’t live in the valley, I helped manage the state forests and got to know the area well, including some people from both sides – the traditional farmers and the new settlers.

I often smiled at the irony. The new residents were attracted to the area because it was “blessed by Mother Nature” – a valley so abundantly verdant and fruitful it seemed to drip with “milk and honey”. Yet, at the same time, they complained about the perceived environmental impacts of logging, land-clearing, and the degradation of the Bellinger River’s banks without understanding that the valley’s beauty was a product of the very land uses they despised.

As I mentioned in my blog about the 1968 fires in the Bellinger Valley, the boundary between state forests on the ridges and private properties on the flats often lay halfway up the slopes. In areas where hippys had bought land adjoining the state forest, our relationship became quite ‘intimate’ over several contentious issues. They were critical of our forest management practices, while we took issue with their use of the state forests for illegal marijuana cultivation.

I recall a particularly frustrating conversation with one of these neighbours, whom we affectionately nicknamed ‘Big Nose’—he had the largest nose I’ve ever seen. The exchange highlighted a fundamental disconnect between us and the newcomers when it came to essential land management in the valley.

I had approached Big Nose on his property to inform him about a deliberately lit fire on the northern side of Horseshoe Road, along the Scotchman Range. With strong winds forecast, it was critical to contain the fire. Our plan was to burn out to containment lines using incendiaries dropped from a helicopter while the weather was still favourable.

Big Nose simply couldn’t grasp why we would use a helicopter to light controlled fires to manage a wildfire. He was convinced that all fires were inherently destructive, and his reaction bordered on hysteria. He just didn’t understand that, in the right conditions, fire can be one of our most effective tools for controlling wildfire spread.

The first big flashpoint – multiple occupancy

While land in the valley wasn’t necessarily cheap, when friends or groups pooled their funds, they could buy a sizeable block of about 150 acres with cleared river frontage, old grazing paddocks in a variable state of rejuvenation and a “rainforest” backdrop. They loved the idea of building cheap houses while ignoring local planning laws. Forming communes, gathering at markets and dances, and living itinerantly, didn’t appeal to the long-term residents.

Despite there being no legal avenue to set up a multiple occupancy, the hippys did it anyway, making them a fait accompli and then supporting their fellow activists who argued for legalisation in their favour. They wanted the freedom to express rural socialism by ignoring legal requirements under the banner of “community” and “sustainable” living.

Surprisingly, the “Shifty” Wran Labor Government in the late 1970s accepted the concept of multiple occupancy. They issued a handbook titled Low Cost Country Home Building showing owner builders, or hippies in the Bellinger Valley, how to build “sustainable” houses but remained silent on sanitation despite houses being built along the valley’s creeks and rivers.

In 1980, the Environment and Planning Minister Paul Landa retrospectively legalised multiple occupancies through an instrument called Circular 44, specifically applying to Lismore, Nimbin and Terania Creek, as Bellingen Council rejected it.

By the early 1990s, multiple occupancies were well-established, such as Chrysalis and Kalang Farm in the Kalang Valley; Homeland, Dreamtime and Patanga on the upper Bellinger around Darkwood; and Shamballa at Boggy Creek. The Promised Land Company on the Promised Land Creek was the first legalised multiple occupancy in the early 1980s. By the time I left, the dream of multiple occupancies was on the nose, with rumours of disputes and disharmony.

Bundagen – a better multiple occupancy model?

A favourite swimming spot of mine was the quiet beach between Tuckers Rocks and Bundagen Headland. One of my duties was looking after the thin strip of littoral rainforest growing out of the sand in the first dune swale, known as Bundagen Flora Reserve.

While the area was relatively undisturbed, it had an outbreak of bitou bush on the foredune. We had funds for spraying, and on calm sunny days, I’d inspect the spraying operation and take the opportunity to go for a swim. I also used to spend weekends on the beach while on fire duty, maintaining radio communication with the fire towers.

Just north of my relaxing spot was Bundagen, known for its hippy commune in the forests behind the beach north of Bundagen Headland.

The Souris family had farmed the area for years and grew bananas. In the early 1980s, they put 240 hectares of coastal land up for sale, expected to attract developers for a 5-star resort. It was a prime coastal block with sweeping views over coastal forests and a long curve of a relatively untouched sandy beach.

The hippys up the valley got wind of the sale. Whether true or not, the conventional story is that they organised a horse ride to the coast, starting from Dreamtime near Darkwood, gathering more riders along the way. After inspecting the land for sale, they believed they could buy and save the land from the developers if they raised enough money.

Over 200 people pooled their resources and bought the land. Among the new owners were professionals like surveyors, lawyers, engineers, doctors and a town planner, who successfully formed a co-operative of equal shareholders and gained legal recognition as a multiple occupancy with Coffs Harbour Council.

Because I was a regular visitor to the area, I developed a beneficial relationship with some of the Bundagen residents to keep undesirables away.

Speaking of undesirables, I will never forget an incident while inspecting a compartment to log on the northern side of Bundageree Creek (Bundagen residents at that time were quite pragmatic about our activities near them). I suddenly saw a guy sitting on a rug under a makeshift tarp completely starkers, with a large container of water and a guitar as his only possessions. When I approached him, I couldn’t get any sense out of him. His eyes were glazed over, so I reckon he had been on the weed or something stronger. I instructed him to pack up and leave, but I am sure he didn’t register what I was saying as I left.

My contact at Bundagen subsequently told me the stranger had turned up unannounced from down south and disrupted the community with his overt drug taking. They kicked him out.

The second big flash point – the “Community Centre”

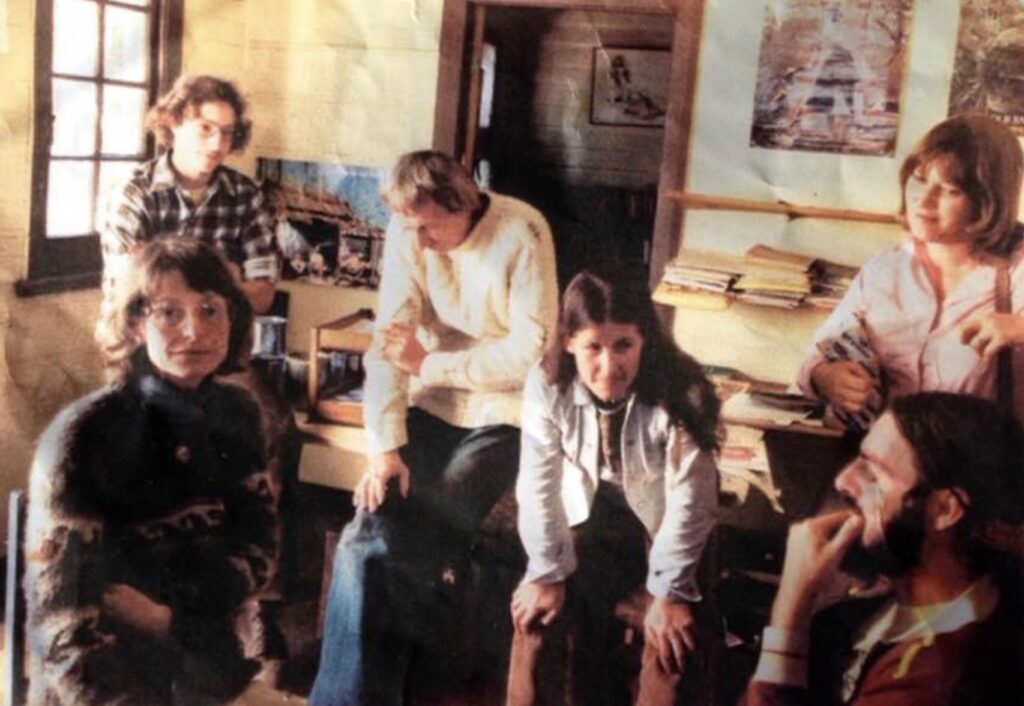

The late 1970s and early 80s in Bellingen were characterised by the demolition of the old primary school buildings, after they had become the “Community Centre” and a focal point for hippys.

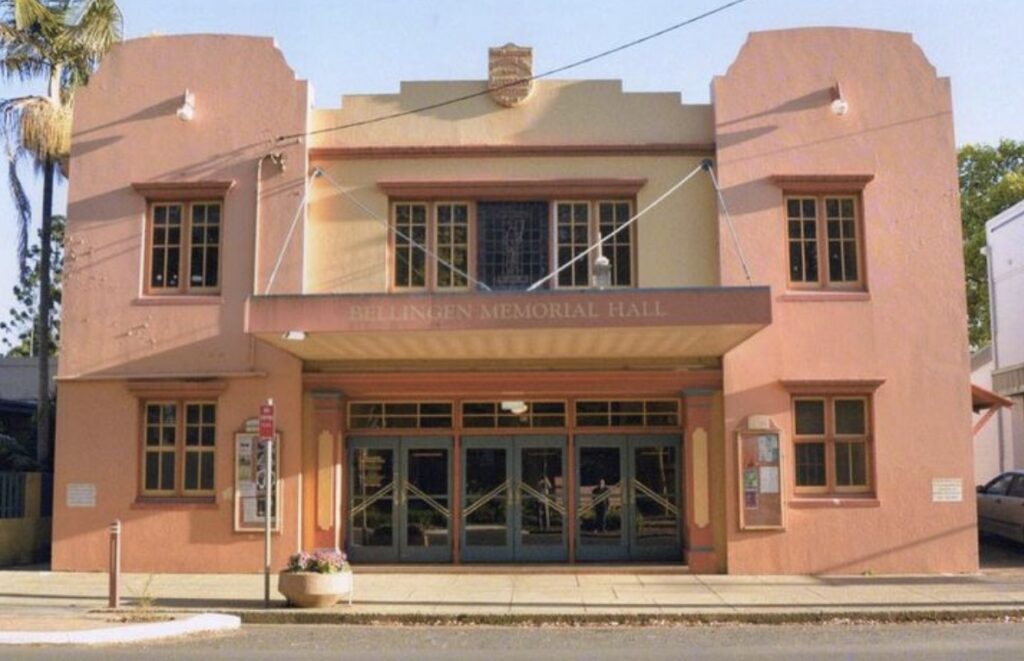

Antagonism spilt over at a meeting in late November 1977 at the Memorial Hall, attended by around 900 people. It was convened by real estate agent and Councillor Peter Sanger, ostensibly about the new arrivals’ lifestyles. Only ratepayers were welcome to speak.

The old primary school buildings across the road had been empty since 1971 after the school was shifted to a larger site at the foot of the Scotchman Range, about half a kilometre away.

In 1974, the state government allowed the local council to resume the grounds and buildings to build a new Council Chambers. Meanwhile, the main building was allowed to be used as a community centre for two years.

There were social problems at the time with high youth unemployment. The council thought that a focal point for the youth to gain support from the community was an excellent way to try and alleviate the problem.

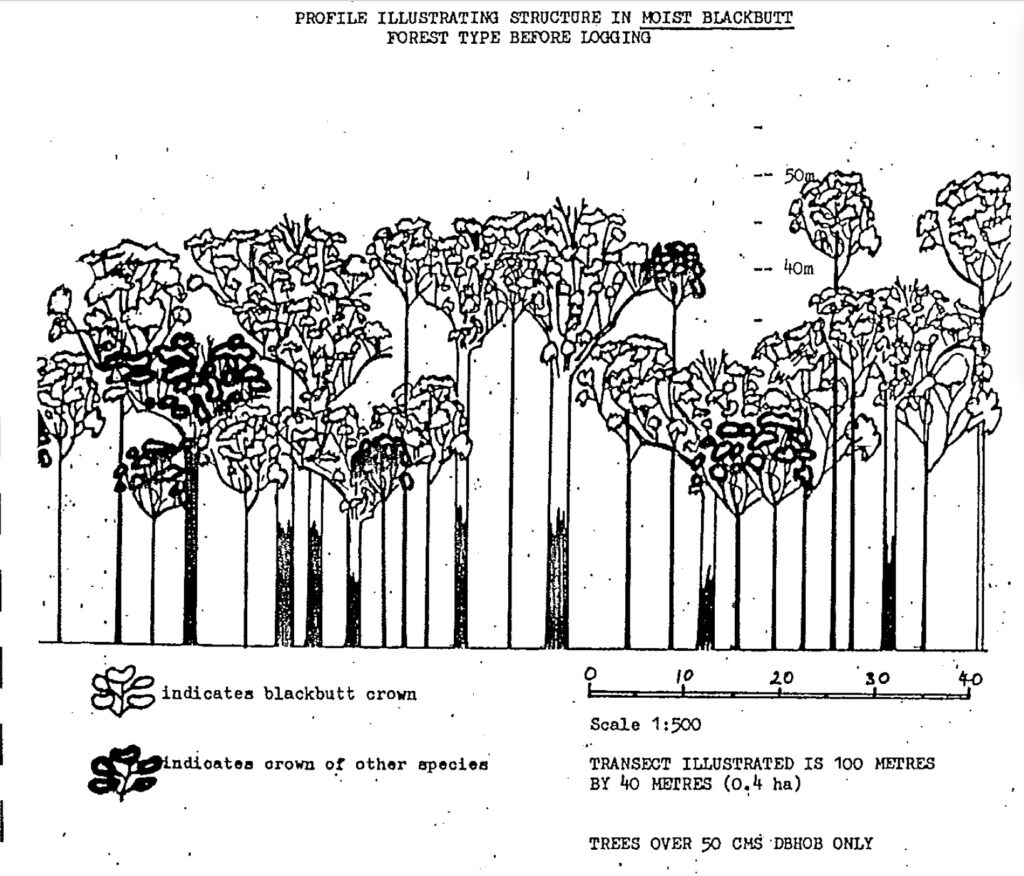

A Management Committee of new settlers and three Councillors ran the centre which quickly became a pseudo environment centre funded by the state government. They called themselves the North Coast Environment Centre and one of their first protests opposed the Forestry Commission’s plans to log the magnificent virgin moist blackbutt stands surrounding the Black Scrub in the Bellinger River State Forest.

This issue gave the Environment Centre something to focus on. The forest stand was an essential resource for medium-and long-term supply viability in the Urunga Management Area. I outlined the reasons for this in my blog on the damaging 1968 fires in the valley.

Contrary to claims by the environment centre, the large “old growth” trees over 100 centimetres in diameter would remain, and the silvicultural focus was to carry out a thinning from below of trees up to 70 centimetres in diameter. The Forestry Commission planned to not touch the magnificent stand of sub-tropical rainforest in the gullies below the logging areas.

The environment centre’s claims of environmental destruction were unsupported by any evidence. The Forestry Commission outlined the results of harvesting a similar forest at Mount Boss State Forest in the Hastings Valley in the mid-1960s, which was subject to a top disposal burn after the logging operations.

Seventeen years later, the regeneration of the Mount Boss area was dominated by large blackwood trees, along with large numbers of rainforest trees in smaller sizes, particularly crabapple, corkwood, coachwood and yellow carabeen. Field plots showed that the area followed the typical temporal pattern in these areas after disturbance – the initial viney scrub phase with quick-growing acacias to large sizes, followed by sclerophyll species and the quicker-growing trees such as brushbox and crabapple. Then, finally, there are the progressively slower regenerating rainforest species.

Anyway, getting back to the “Community Centre” – the traditional locals were not happy. The Management Committee hadn’t done anything with the buildings. Only a small number of youngsters attended the youth support scheme. There were accusations that some of the activities run by the Environment Centre were illegal, and there were serious questions about what it stood for.

One prominent businessman at the meeting argued that the personal hygiene of the adults and children at the markets outside the centre had a distinct smell of marijuana. This was a time before the cafe culture had arrived and the only prominent drug around town was not caffeine but dope. He also argued training courses such as making leather belts, planting seedlings, and painting did not help train the youth to enhance their employment chances.

The two year “lease” was up, and half the attendees at the meeting wanted the Management Committee sacked and a community centre set up in Darkwood or Upper Kalang where the hippys lived. The meeting put a motion, and a majority, about 60 per cent, voted to sack the Management Committee.

The only sure thing to come out of the meeting was the division of the community along the traditional farming/timber industry lines versus the new, young settlers that preferred a different lifestyle imbedded with “nature”.

The media had a field day reporting on the highly charged meeting. Adele Horin from the National Times utilised hyperbole to the extreme, alluding to “roaring crowds of rednecks”.

Despite the hype after the meeting, particularly from some of the local media, the Management Committee was never sacked, and for the time being, the “Community Centre” continued.

Another public meeting in 1979 sought to replace the “Community Centre” with another building, sparking opposition from alternate lifestylers. They approached the state Heritage Council and presented a report prepared by the Coffs Harbour Public Works Department district architect, Doug Ransom, but after inspections, it was deemed not historically significant.

At dawn on Friday, 29 March 1981, just days after police seized 962 marijuana plants during a series of drug raids in surrounding areas, a contractor began demolishing the building. About 100 demonstrators were there to stop the work, and as fast as the workers pulled down the building, the protesters were putting it together again.

Due to a lack of necessary approvals, a Conservation Order temporarily halted demolition.

The Town Clerk called the opposition “mob rule by minority”. They quickly mobilised and intimidated local shopkeepers to support their cause by threatening to boycott their businesses. It started getting ugly.

The Town Clerk was exhausted after continuous calls and meetings with the protesting group. “I’m going to the golf club for a beer”, he famously quipped.

The council finally demolished the building once the Conservation Order lapsed, ending an infamous series of events highlighted by community division.

Growing dope

Growing marijuana or dope was a significant money earner in the valley during the 1980s and ’90s, maybe even still so. The growers tried to keep it a secret from the public record and the local cops but were unsuccessful. There were arrests. Police convicted a couple of guys of possession and use of marijuana near Marx Hill. Another, who claimed to be a non-user, was convicted of possession after police found dope in his shed at Kalang.

Cannabis brought money to the valley after dairying declined and the timber industry production levels had peaked. The cash economy flourished, reflected in high childcare rates. Many claimed the new settlers from the city learnt gardening skills to help them successfully grow dope. The growers undoubtedly set up some elaborate schemes. Judging by the size of the plots, they weren’t just for personal use. For some, it was a business, a means to make money, and lots of it.

The growing and harvesting of marijuana was an open secret in the valley. Celebrated filmmaker Peter Gailey made a film about it using Peter Geddes’ home movies. Geddes arrived with his young family in the 1970s as one of the first hippys.

The big growers wouldn’t grow cannabis on their land. With so many state forests clothing the upper slopes of the ranges, they set up dope plantations in the public forests.

As a forester, I frequently found dope plantations, some of them very elaborately designed and built. The challenge for the dope growers was to supply water for the plants and keep them hidden. They managed to put them in secluded parts of the forest with elaborate irrigation lines.

Proposals to harvest compartments adjoining private property often met with environmental complaints, but we soon realised it was a front to protect their dope crops.

The loggers avoided conflicts with growers, often working around dope plants to avoid vandalism.

I will never forget one I stumbled onto while fighting a fire. I was supervising some crews backburning in less-than-ideal conditions. A strong north-easterly made our work slow and laborious. Whenever an ember drifted over the fire trail and lit the fuel, we attacked it and put it out.

While we were working, a couple of guys on motorbikes kept driving past to see what was happening. I thought they were neighbours, anxious about the fire threat to their property, but they didn’t stop for a chat.

However, later in the day the inevitable happened and we saw smoke higher up the ridge on the wrong side of the trail and realised our efforts were in vain as the fire was heading towards the top of the hill. I had to assess what we faced the next day, what resources we needed, and what machinery I had to organise overnight. I walked along what I thought was a wallaby track into the bush. My focus on the fire was replaced by what I came across.

Built into the head of a gully was a few levels of rock terracing that supported many marijuana plants. There were many plastic barrels full of water and piping running back down the bush, presumably to a makeshift dam with water. It was impressive and it dawned on me then that the bike riders from earlier in the day were only worried about their dope crop, not the fire itself.

We reported the find to the local police, and they were ambivalent, perhaps because they knew they needed more proof for a conviction than my hunch about two guys on motorbikes.

The next day, I instructed the foreman to make sure they completely burned out that section of the bush!

The Bellingen Environment Centre

By the time I arrived, local government politics in the valley was fascinating and animated, often making headlines. In 1987, Mayor Gordon Braithwaite, frustrated at the lack of support for what he believed were vital residential developments, recommended the new Coalition’s Local Government Minister sack the council and call for new elections. Although this didn’t happen, it was significant local news. Ultimately, Braithwaite was defeated for mayor at the 1991 election and was replaced by Sue Detheridge, although he remained a Councillor.

The dysfunctionality of the council was frequently in the news, alongside the emergence of a new and independent Environment Centre free from hazy “Community Centre” politics. They opposed anything that didn’t involve people dressed in batik chanting “kumbaya” in the forest.

Environmental issues were brewing all over the valley. Initially, the Bellingen and Plateau Conservation Society was formed mainly to oppose the removal of three sizeable remnant tallowwood trees near the Promised Land.

It eventually morphed into the Bellingen Environment Centre and one of its first targets was Gus Raymond, who ran AWC Raymond Pty Ltd, a company that extracted gravel from the river near Glennifer.

It was commonly believed that a build-up of river gravel after flooding caused erosion of riverbanks due to redirected water flows, with subsequent floods replenishing the gravel taken out. The problem was most likely exacerbated by forest clearing right to the riverbank on farming land. However, the Environment Centre argued that commercial-scale gravel extraction destabilised the river. Despite their complaints, the council, being the biggest gravel user in the valley, ignored them.

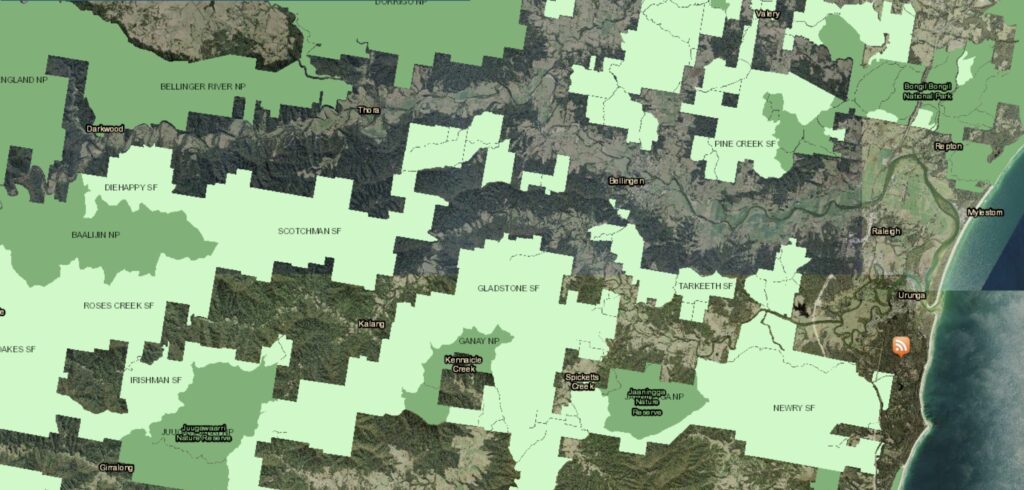

When I arrived, activists had established many environmental groups to fight specific campaigns. There was one in the Upper Kalang to stop logging, another to stop a tourist resort near Pine Creek, and the radical North East Forest Alliance had just formed.

The Environment Centre became the front for all these disparate activist groups, incorporating them with a constitution. Using this legal legitimacy, they took Raymond to the Land and Environment Court and gained an injunction to stop the gravel extraction.

At the same time, the Environment Centre held its Annual General Meeting. Many industry people and their supporters attended, demanding membership and even entertaining ideas of taking over. They timed their intervention exquisitely as the Environment Centre did not have a quorum for the meeting.

Unfortunately, the protagonists quickly lost interest, and the Environment Centre maintained its original make-up. It also went on to win its court case against Raymond, even as the council ignored the Department of Water Resources’ order to suspend gravel extraction from the river.

The Environment Centre also purchased a building to operate from and set up the Friends of Bellingen Environment Centre to avoid losing their asset if somebody sued them, which was a strong possibility given their unsubstantiated activist claims.

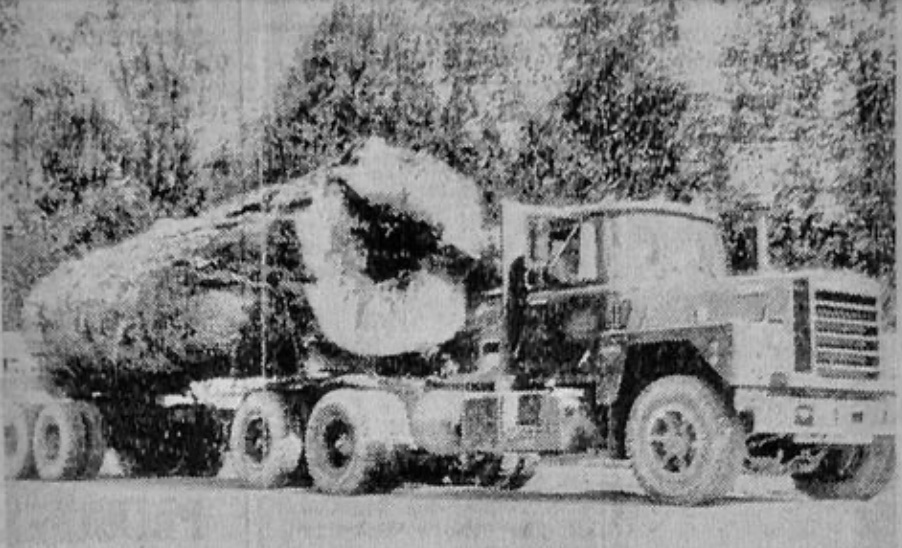

I recall we were logging at Tuckers Nob, which had excellent timber. Fallers felled a large tallowwood tree, containing 54-cubic-metres. It was cut into three logs, each transported as a single rider through Bellingen to the Thora sawmill. The Environment Centre were apoplectic when they saw or heard about the log trucks coming through the middle of town.

Final thoughts

In 2022, I returned to Bellingen to research my 1968 fire story. Just two months ago, I house sat at the Promised Land Company commune, once again blending quietly into the local scene.

Bellingen still holds onto the alternative, vibrant atmosphere I first encountered in the early 1990s, but the changes are unmistakable. There are now cafés that serve gentrified dishes—roast pumpkin, kimchi, tempeh bowls with miso dressing and seeds—organic food options are everywhere, and there’s even a Middle Eastern street food outlet. It’s a far cry from the simpler fare of the past.

The public notices reveal much about the town’s spirit: bamboo floor-making classes, flamenco guitar lessons, a concert titled Forest Rhythms aimed at “saving” the Promised Land from supposed rapacious loggers, and a LoveFest at Thora. For those seeking even more enlightenment, there’s a Brain Master Class led by a world-renowned somatic body worker.

But the further you drive from the town’s core, to places like Darkwood and Upper Kalang, the illusions begin to crumble. The valley feels frozen in time, its once-thriving industries long gone. There’s a ragged, unkempt quality, echoed by the forests in the new national parks—neglected, overgrown, and untended.

The same endless promises I heard in the early ’90s still echo: the valley would become a self-sustaining, nuclear-free, eco-paradise powered by “appropriate technology.” Yet, after all these years, nothing of substance has materialised. The communes and remote properties remain on the grid, solar panels and wind turbines are scarce, and cows still graze the paddocks. Timber houses, complete with polished kitchen benches and cozy wood heaters, still define the landscape. To my dismay, I saw new forest clearings for power lines, supplying the many new dwellings creeping into the upper arms of the valley.

It’s no different from the days when small dairy farmers scratched out a living here. The same struggle continues, only now it’s wrapped in a tangle of ideology that never delivered.

What remains is a disheveled valley haunted by a protracted culture clash. Who won? Who cares? What’s certain is the valley lost.

While Peter Gailey’s recent film offers a romanticised view of the settler invasion, the forests on those lands tell a harsher story. Left untended, they’ve become choked with biomass, waiting for the spark of an inevitable bushfire. The weeds that plagued the area 30 years ago persist, bolstered now by roadside bamboo clumps planted by the hippys.

I shouldn’t be surprised. I once thought that the gentrification by wealthy, educated city folk seeking a tree change might bring a fresh start, clean up the place, and restore some vitality. And while pockets of change are visible, they remain exceptions, not the norm.

During my recent visit, I spent time by the Bellinger River and spoke to some older locals. Bellingen’s famed swimming spots—The Island, Red Ledge, and the caravan park pool—aren’t what they used to be. The river isn’t as deep anymore. We speculated that halting river gravel extraction might’ve played a role, an unintended consequence of misguided policies.

There was the comment that the swimming spots went downhill when the council removed a lot of gravel from the river on the southern side of The Island in the decade or two after the 1950 flood. Subsequent floods, such as in 1974, rearranged the flow over the depleted gravel beds and the northern side silted up.

We did agree, though, that the river was at its best when the council allowed regulated gravel extraction and dredging operations to make up for the wilful destruction of vegetation on the riverbanks.

The Bellinger Valley was once a vibrant landscape, shaped by traditional European land practices and active forest management. But then new settlers arrived, condemning these practices as destructive and waging a relentless campaign to dismantle them—a battle they’ve nearly won.

Today, community notice boards are still plastered with pamphlets in their fight to halt the logging of local forests, this time targeting the flooded gum plantations established by APM in the 1960s on former dairy land in the Promised Land area. Their arguments twist logic, claiming logging is driving koalas to extinction while simultaneously acknowledging that these plantations are teeming with koalas.

One thing is certain: since the takeover by alternative lifestylers, the valley beyond Bellingen township has remained stagnant, a shadow of its former self as traditional farming retreated.

Those of us who lived through the changes, especially the older generations, saw the degradation firsthand. We spoke out, but our voices were drowned out by those convinced they knew better.

Thanks Robert for this interesting article.

Hippys in their original form dreamed of utopia and a new way of life, consisting of free willed communities, propped up with ideas that were unattainable and quite lawless.

They still live amongst us, as I witnessed firsthand while residing in the town of Maleny on the Sunshine Coast hinterland, where the free spirit thought process that you described in your article is evident, and easily encountered with a stroll through the town centre.

Your description of the Bellingen Forests and pop up communities, along with their attempts at alternative industries, and protests of anything they disapprove of, very much mirror the townships jotted along the Sunshine Coast.

After all these years, it appears nothing much has changed with alternative lifestyles, hippys, and fumbling, bumbling bureaucrats having a say on issues they have little understanding of, and certainly no practical experience or skills to enhance the natural beauty of our forests areas.

Thanks Robert.

This story provided flashbacks to the 1970s and 80s as the alternate life stylers moved into remote private properties adjacent to state forests between Eden and Bombala.

A SETA Facebook post of 27 March 2024 documents one of the 1981 fires in the Bombala forestry district. The fire started on about 16 September 1981 on an alternate lifestyle block and quickly moved into a steep area on the adjoining state forest. On an initial inspection of the source of the fire, I remember the marijuana plants growing in pots embedded in the sand on the edge of the creek.

In the late 1970s, when on a fire trail inspection day, I had my initial visit to this recently established multiple occupancy block. There were a mix of caravans and tents adjacent to Stockyard Creek, with the first pole frame hut, with river stone floor under construction.

One of the residents stumbled out of a tent on our arrival, with glassy eyes and no interest in talking. I turned to a young boy, about three years old. He had come out with a cereal bowl in one hand and a spoon in the other. The poor little bugger was filthy and his breakfast looked like a mixture of sheep pellets and chook feed. As I started to speak, his mum emerged. Her first words were: the boy can’t talk, but I can. What der ya want?

I have no empathy for the teens and young adults that chose the alternate lifestyle, but I feel for the offspring of these, often drug addled idiots. I occasionally wonder how this little boy fared and whether he made a decent, productive life for himself, in spite of his parents.

“A magnificent blackbutt regrowth forest at former Pine Creek State Forest ….. logged at least five times since settlement, subject to intensive Timber Stand Improvement works and heavily snagged (old trees removed from near roads and firebreaks). It supports yellow-belied gliders, greater gliders and powerful owls. It is so magnificent, it is now part of the Bongil Bongil National Park. A wonderful credit to the active and professional land management by foresters.”

Your expert caption descriptor Robert can be applied to almost every addition of forested landscapes to the National Park estate in Queensland over the past 3 decades.

ps Robert

As a Queenslander, it is impossible not to mention the finest example of forest estate transfer ever; Fraser Island hitting the jackpot as a World Heritage listing after 100 years of Qld Forestry management.

I presume you will highlight this tragedy and the loss of crown estate rent in your forthcoming book.

Certainly will Gary. In fact, I am polishing off the chapter about the “blackbutt story” right now.

Keep up the great work and reporting Robert.

Thanks Robert for a useful and objective potted history of the valley that deserves a better life than being buried in a blog. Perhaps post-Fraser you can bend your mind to a north coast forest history that might incorporate this piece?

Re your first photo of farmers crossing the Bellinger River. This was not the 1950s flood. This was a flood circa 1907-08. The bloke on the horse in the hat (bloke not horse) at the back is EHF Swain who was the local forester at the time. I have copies of two of Swain’s photos of this incident, one converted to a post card, on the back of which Swain has written:

“E.H.F. Swain (forester) and a settler, wife & new baby crossing the 40th ford up the Bellinger River from Bellingen about 1907. The husband had been washed down the river a mile as his first attempt. I had hauled him out.”

We don’t know who actually took the photo. If you would like copies send me an email.

And apropos Pine Creek State Forest – this was the happy hunting ground of Australian Forestry School students in the 1950s -60s who under the tutelage of that doyen of eucalypt silvics, Dr. Max Jacobs carried out silvicultural treatment of the blackbutt forests and surfed au naturel off those marvelous beaches…

Thanks Ian for the correction. I will adjust the caption. I had seen a photo of Swain crossing the river on horseback outside of a flood. I must track it down.

Thank you very interesting. My late husband, Henk Mulder and I moved to Bellingen in late 1971, in search of a better life. We weren’t hippy or alternative lifestylers. We set up a business at East End, manufacturing fly screens and doors, and made a moderate living.

I joined the Community Centre management committee. Later, Henk became a well known builder in the valley, as well as refurbishing many public buildings which had fallen into disrepair including the Yellow Shed.

I was interviewed by Peter Gailley for his movie.