At the start of WWII, Australia was unprepared for a prolonged conflict, processing just enough petrol reserves for three months and limited storage capacity.

Though fuel rationing wasn’t immediately imposed, the government urged citizens to conserve petrol, hoping to avoid drastic measures.

While the motor industry strongly petitioned against any fuel rationing, by 1 October 1940, however, fuel rationing became a necessity. The Director of Economic Planning, Ernest Fisk said his rationing plans would:

Make a man ashamed to use his car unnecessarily.

In typical bureaucratic fashion, the rationing system was complicated and produced a lot of paperwork. The government divided all users into classes, such as private cars, delivery vehicles, buses, taxis, trucks, industrial transport and farm machinery, and they determined priorities for each classification. Ration scales considered the horsepower of vehicles so that they could calculate miles per gallon before allocating allowances. Finally, the various groups were divided into essential, preferred or ordinary user status.

Over a million civilians applied for petrol licences, enduring a bureaucratic process just to receive ration tickets.

The fall of Singapore in early 1942 only worsened fuel shortages, and the government strictly enforced rationing through the Liquid Fuel Control Board (LFCB) whose main job was to ensure an equitable supply of petrol. They were supported by similar Boards set up in each state.

In Queensland, a circular was sent by the Department of Forestry to all sub-districts instructing staff to “drastically curtail” the use of cars. They encouraged worker camps in the bush to be shifted more frequently and encouraged men to walk greater distances to work.

The crisis led to an unexpected hero – charcoal.

Producer Gas Units

Even before rationing took effect, the government promoted gas producing units powered by charcoal as an alternative fuel source. Despite their unpopularity, these cumbersome, inefficient devices soon became essential.

To convince motorists the government was serious that the units were a viable alternative, they planned to install 20 per cent of Commonwealth vehicles with the units.

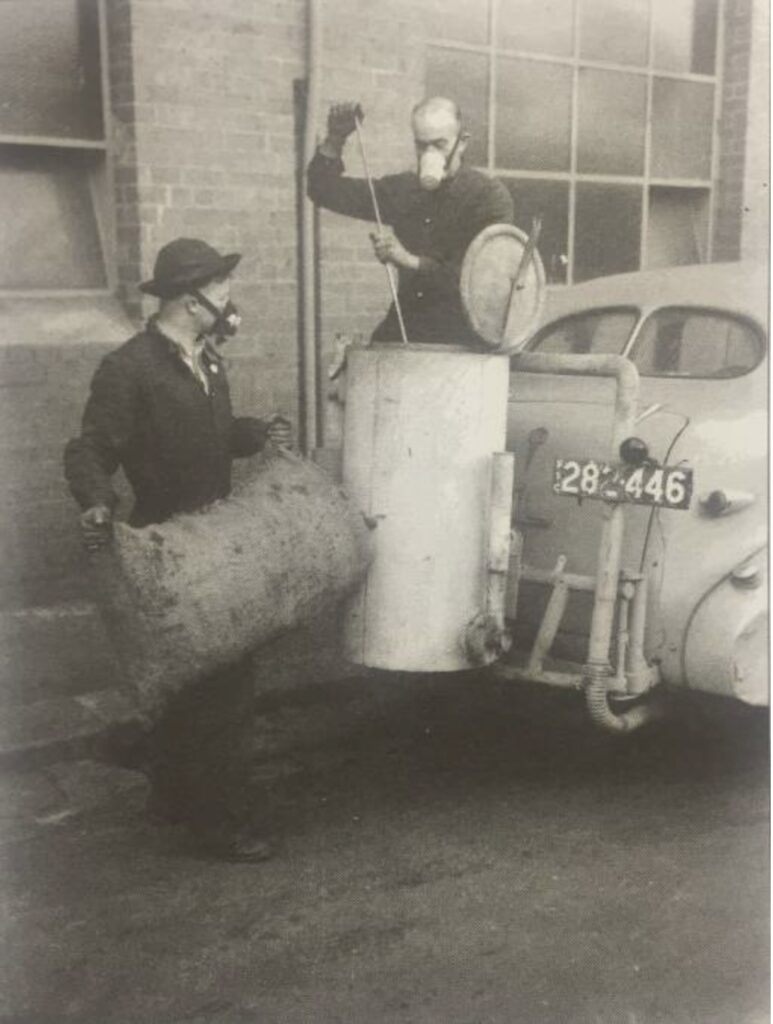

Burning charcoal in drums, the size of washing machines called producer gas units, kept cars and trucks moving when petrol was scarce. Suddenly, these units appeared on rear bumpers or a platform, carried in a separate trailer or squeezed into the boot. It was the preferred source of producer gas for internal combustion engines.

By today’s standards, it wasn’t much, but when fuel was scarce, the wood-burning cars kept a nation on the road.

The federal government set up a State Charcoal Branch and a Power Fuel and Water Supplies Committee to produce and control those materials. The common brands of gas producer units were Ajax, Electrolux, Bawden, Victory, Star, Harris, Brig, WGK and Pederick.

A producer gas unit had the benefit of being cheap and operated on a local source of fuel. Charcoal was relatively simple to produce, but they were universally hated by those compelled to use them.

The fire created by the slow re-burning of charcoal created hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The unburned gas was piped to the intake manifold through several felt filters, which could just about power a car uphill with the wind blowing from behind.

However, these devices had serious drawbacks. They were underpowered, dirty, smelly, prone to catching fire and occasionally even exploded.

Getting the vehicle started was an elaborate ritual. First, the driver had to fill the water tank. Loose charcoal needed to be poked down from the top of the hopper to fill the cavity made by the previous fire and the ash cleaned out. The engine was started on petrol before the ash-pan door was opened, and an asbestos wick or rag saturated in kerosene was inserted and lit. The spark would fire the engine’s cylinders.

Back draughts sometimes burnt the eyebrows off unsuspecting motorists, and the ash would turn a pretty white dress grey in no time!

Once the fire was blazing, the trapdoor was closed, and in theory, the vehicle was ready to move, using petrol and then switching over to gas. The petrol supply could then be turned off, the water valve opened, and the gas/air mixture adjusted while moving. The process took at least 15 minutes and had to be repeated if the vehicle stopped for over half an hour.

Resistance in Queensland’s logging industry

In Queensland, even though considerable work was done on charcoal production and the adaptation of motor vehicles to use producer gas units, the forestry industry complained very loudly, particularly those producing timber for military purposes in the rainforests of North Queensland.

The Commonwealth initially argued that because the timber industry was an essential provider of products for the war effort, logging machinery, including trucks, had to continue operating should there be a severe petrol shortage. Thus, they decided the owners fit gas producer units to their machinery.

In August 1942, the Commonwealth issued notices compelling log trucks to fit producer gas units, prompting uproar across the state. The timber industry argued strongly that fitting producer gas units was impractical.

The unit had to be fitted as close to the engine as possible which caused problems. The addition of weight on one side caused balancing issues on a full load of timber. There was also a loss of traction on the rough gravel roads and if the unit was mounted underneath, the trucks couldn’t negotiate the creek crossings.

James Dawson, the District Forester at Atherton, aptly captured the industry’s frustration in a letter:

“As you know, Gas Producers on heavy hauls are useless and only encumber the lorry and, in the long run, are responsible for more use of power fuel and reduce loading capacity, thereby doing just the opposite to what some ignorant official who got the brainwave expects.

Would you take up with the officials responsible and see that sanity prevails, please.”

The Department of Forestry was required to make representations for individual truck drivers to get exemptions rather than obtain a blanket exemption. In May 1943, the state-based LFCB agreed to waive the notices and requirement to install producer gas units.

However, when the owners purchased a new truck, they were still notified to install a producer gas unit. This was because the Commonwealth insisted notices still had to be issued. It was then necessary for the truck owner to apply to the Director of Emergency Road Transport that their truck was engaged in timber haulage and seek an exemption.

The bureaucratic process remained a source of immense frustration.

The charcoal boom

The production of charcoal is one of humanity’s oldest crafts and arguably the first true chemical process discovered by humans.

Dense hardwoods like red ironbark, red box, grey box, yellow box and river red gum were ideal for gas producer units as the greater fuel weight per hopper load provided a greater range.

The timber had to have good mechanical strength and be free from dust and fines which clogged the filters, and showed the original grain. The preferred sizes of charcoal lumps varied with the unit’s design but were in the range of 6-36 millimetres.

The producer gas units required charcoal to be carefully produced – clean, dry, shiny and capable of burning with minimal smoke.

The demand for charcoal was so great during the war that firewood itself became scarce and had to be rationed.

The Victorian Forests Commission (VFC) established the State Charcoal Branch to meet the demand, producing about 2,000 tons of charcoal weekly. By the mid-1942, an estimated 221 kilns and 12 pits were producing charcoal in State forests and at least 50 to 60 private charcoal retorts were set up in the Barmah Forest alone. There were also over 600 commercial kilns operating on private property.

VFC built the brick Kurth kiln at Gembrook, the only commercially sized charcoal kiln in Victoria. The design facilitated the continuous loading of timber at the top and the recovery of charcoal at the bottom. Construction occurred in 1941-42, and it began operating in mid-1942. However, structural problems and an oversupply of charcoal from private kilns meant that the Kurth kiln was only used intermittently in 1943, and the VFC shut it down soon after.

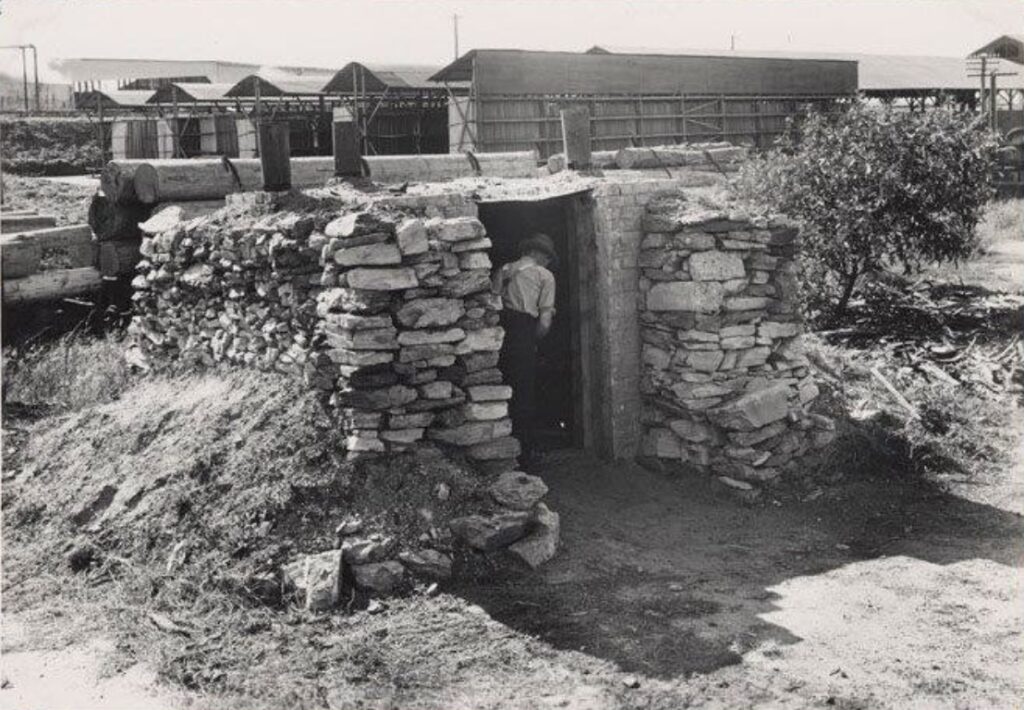

In contrast, Queensland, relied on charcoal produced privately. However, in April 1942, petrol stations found it challenging to get a regular supply of charcoal for motorists with producer gas units. They called on the Department to produce charcoal using the timber from state forests. In response, many charcoal pits were cleared, dug and bricked around the state, quickly creating an emergency supply of charcoal.

One area which produced charcoal on a commercial scale was Beerburrum where waste timber from the clearing of native forests for pine plantations was made into charcoal.

The Department initially established emergency charcoal depots at Dalby, Atherton, Gympie, Warwick, Townsville and Roma Districts to try and regulate the supply of charcoal for the producer gas units. They were keen to ensure that charcoal producers maintained quality and did not exploit prices during low supply and high demand. Each depot was required to set aside 1,000 bags of charcoal for emergency purposes and kept separate from local requirements.

Forestry staff built several brick-lined charcoal pits in the state forests in late 1942. Even on Fraser Island, staff built vented pits using bricks from the abandoned McKenzie settlement. By 1942, there were 89 pits in the state producing nearly 45,000 bags of charcoal. Production peaked in 1944 when 99,725 bags were produced.

The importance of timber in assisting with the war effort was very high. While products produced from saw and veneer mills were in high demand, charcoal and firewood were also an essential and lesser-known component that contributed to the war effort.

Firewood also played a vital role in keeping Australia’s homes and businesses running. For example, the Victorian government launched an Emergency Firewood Program, producing and distributing hundreds of thousands of tons of firewood to Melbourne and other metropolitan centres, a critical substitute for rationed gas and electricity. But that is another story to be told, meanwhile here is an excellent short article about the program.

Despite the vital role these timber products played in sustaining the war effort, the end of the conflict marked the swift decline of both the charcoal and firewood industries. As petrol became readily available once more, many abandoned charcoal kilns and depots remained as relics of a bygone era.

Good one Robert with some interesting side stories and photos. Some of the alien interns were employed cutting firewood and producing charcoal.

I remember these burners in Brisbane during the war; the C of E minister across the road from us had one fitted to his 1938 Ford. It smelt something awful and made a strange noise but as kids we found it an exciting bit of gear and to ride in said car was a treat – a precursor to a rocket ship.

I have a 1943 pic of a QFS truck fitted with a gas producer which I will send via email as I can’t seem to attach here.

Ian

A most interesting read. I was aware of the gas burners but thought they were only in UK during WW2. I have wondered, could they be improved today and used?