To generate hydropower you needs lots of water and steep hills – both things Tasmania has in abundance.

In the heart of Tasmania’s rugged southwest, a region once almost uninhabited since settlement and defined by its natural lakes, impenetrable forests, and fierce winds, a remarkable story of human ingenuity unfolded. This remote area, receiving four meters of rainfall annually, seemed an unlikely place for grand engineering feats. Yet, it became the stage for one of Australia’s most ambitious hydroelectric developments.

It all began in 1895 when Launceston Council built Tasmania’s first hydroelectric station on the South Esk River. This pioneering effort was soon followed by the Waddamana Scheme in the Central Highlands in 1911, initially undertaken by the Hydroelectric Power and Metallurgical Company and completed by the Tasmanian Government Hydroelectric Department after the former went broke. In 1930, that department evolved into the Hydroelectric Commission (HEC) embarking on an unbroken series of 38 power schemes that spanned 64 years, culminating in 1994.

The HEC’s mission was clear: to harness Tasmania’s abundant natural hydro resources for the benefit of industry and the community. HEC grew into the most formidable government business in the nation, constructing some of the country’s largest civil work projects.

Employing top designers and engineers, HEC reached significant hydroelectric achievements that drew global admiration. So much so, they designed and built colossal reservoirs that symbolise human ingenuity and determination. They proudly became the world pioneer in rockfill dam building, and many of its major civil projects were unique.

The Gordon Dam Scheme

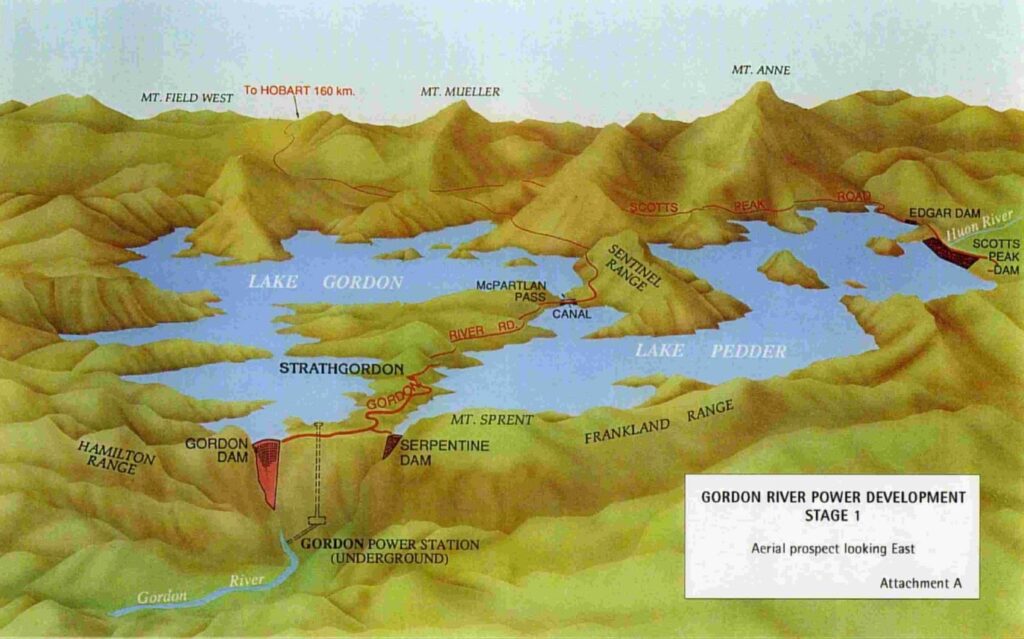

One of their grandest projects was the creation of Australia’s largest inland freshwater lake, envisioned for the southwest of Tasmania. This monumental scheme included the construction of three rockfill dams – one at Lake Edgar, another at Scotts Peak at the southern end of the proposed lake, and the third on the Serpentine River near its junction with the Gordon River.

The HEC’s ambitious plan involved damming the Serpentine and the Huon Rivers to form a single lake, with water flowing to Lake Gordon via a man-made canal at McPartlan Pass, thereby flooding the existing Lake Pedder. A 140 metre high concrete arch dam would be built in a deep, narrow gorge to create Lake Gordon, to be constructed in the Gordon Gorge between the Hamilton and Wilmot Ranges storing the flow of Tasmania’s largest river for power generation in the Gordon underground power station.

Initially, access to this remote area was limited to foot or boat until helicopters began facilitating engineering reconnaissance in 1956. The helicopters were flown each summer, transporting engineers, geologists and hydrologists, diamond drills, accommodation and food to sites along the Gordon and Serpentine Rivers. When the weather closed in, they were isolated for weeks.

The work involved cutting access tracks, installing pluviographs, excavating adits, aerial geodetic and topographical surveying, precise levelling and geological and geophysical mapping.

Overall, the project involved four dams, a small canal, the headrace and tailrace tunnels.

In the mid-1960s, an 80-kilometre road was built to the dam site from Maydena. While the road was being built, helicopter access to the investigation camp at the site was limited. The HEC submitted a proposal for the Gordon Dam to the Tasmanian parliament in 1967, which was approved soon after.

Construction

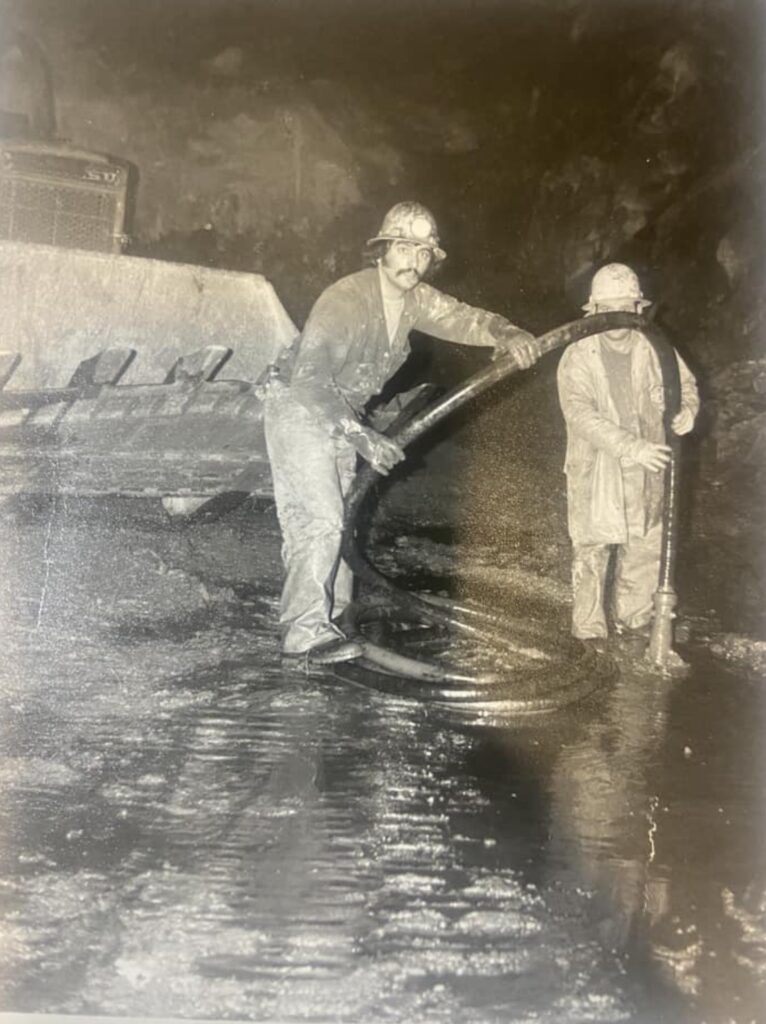

The construction of Gordon Dam, which commenced in 1972, faced significant challenges due to the isolated landscape and unfavourable weather conditions.

The geology of the rocks forming the gorge was quite complex, and the dam had to be carefully sited to avoid prominent faults in the abutments. Major excavation was required on the left abutment, and there are extensive tunnels at several levels in both abutments for foundation grouting and drainage purposes.

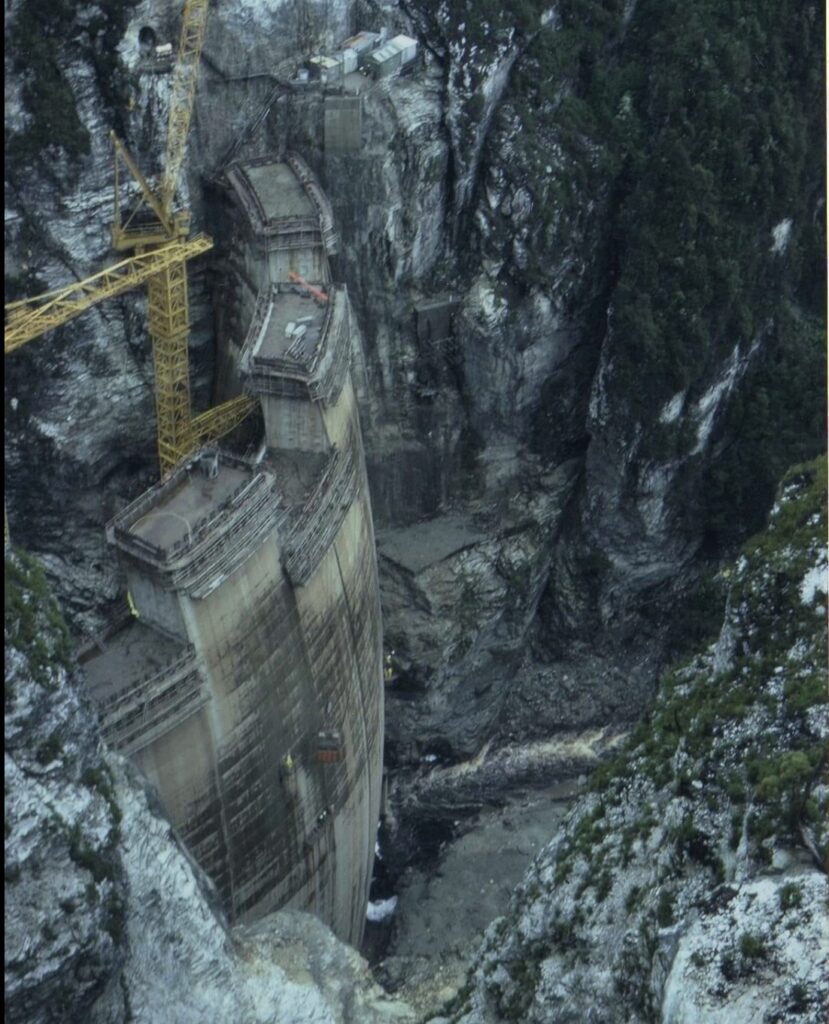

Principal design engineer Dr Sergio Giudici, a premier expert on arch dams in Australia, led the project. He was supported by “Electric” Eric Reece, the Labor Premier who championed hydroelectric power in Tasmania.

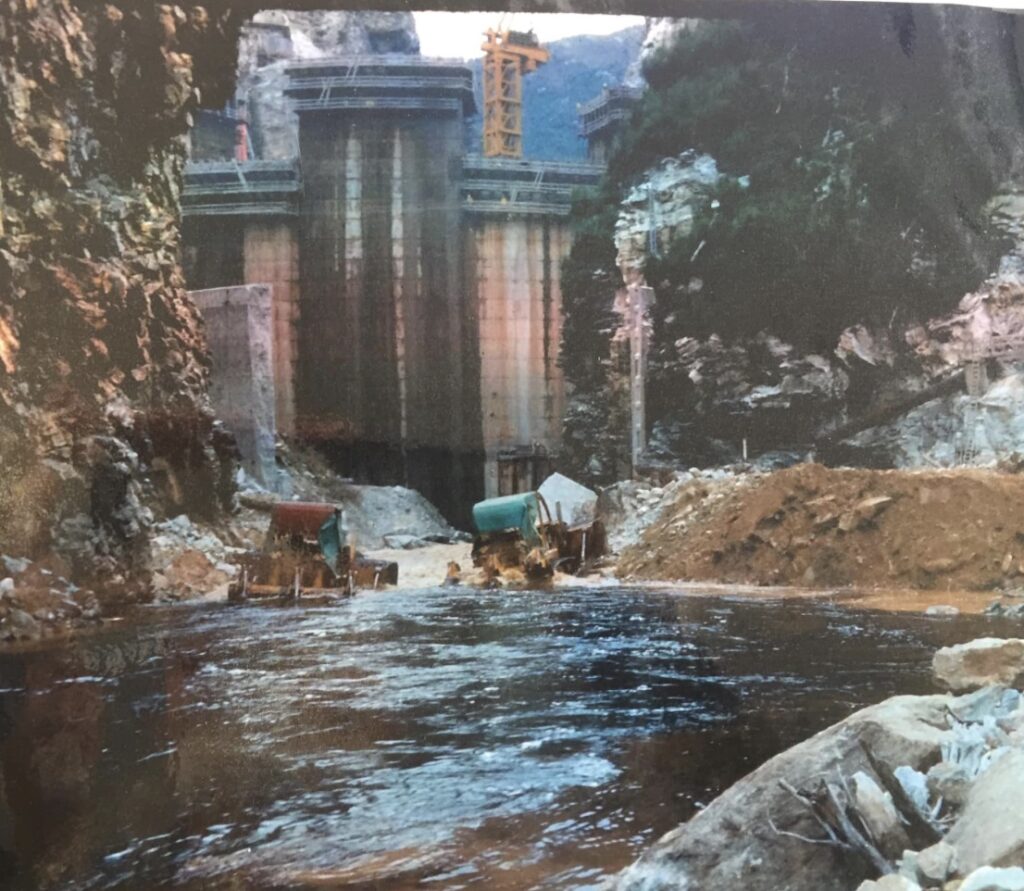

To construct the massive dam inside the narrow gorge, it was necessary to divert the river via the creation of a temporary 22-metre-high coffer dam and a 340-metre diversion tunnel. Because the river was subject to sudden severe flooding, the eight-metre-wide tunnel was designed to take six times the average flow.

The main dam abutments on the gorge face had to be cleared to provide a good foundation. Because of the distance across the height above the main gorge, the standard means of firing pilot ropes for the cable car was impossible. So, a helicopter was used to lay the first nylon rope from side to side. Heavier ropes were hauled across until the final three-inch steel cable was laid.

The height of the aerial cableway to the bottom of the gorge was equal to a 60-storey office block. It was typically used to carry equipment, rigs and other materials for building the dam, but it also brought the workers across the gorge.

Initially, the face of the gorge was a mass of walkways, but later, the primary access to the gorge was via the haulage way built up the dam’s left abutment.

By the time the Gordon Dam was completed in November 1974, it stood as Australia’s highest arch dam at 140 metres, utilising 154,000 cubic metres of concrete. Its double-curvature design minimised concrete and costs while maximising structural strength. Double curvature means it is curved horizontally and vertically, which is crucial for evenly distributing the immense pressure exerted by the water on the dam wall.

The dam’ s immense height ensured maximum water storage capacity, essential for consistent energy supply and mitigate the need for frequent spillage.

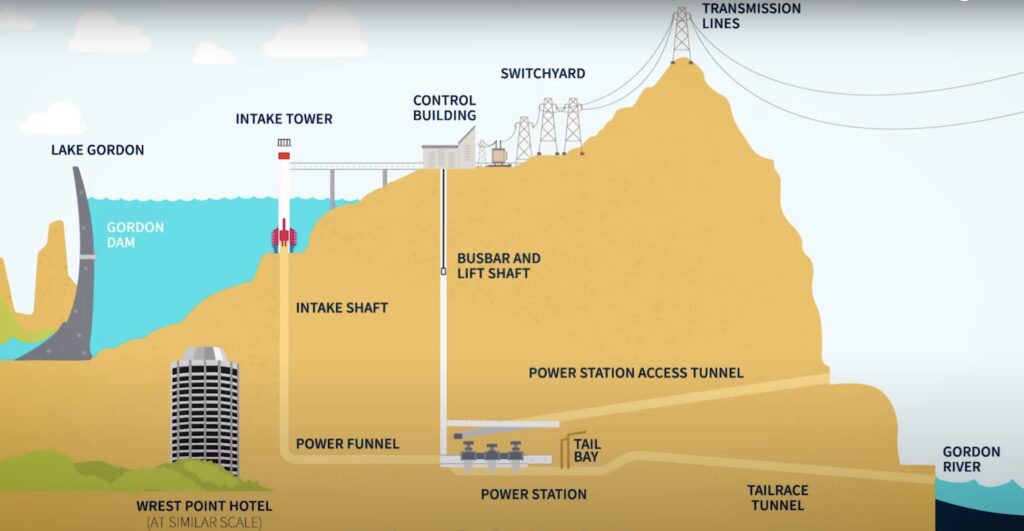

The power station, located 183 metres under the surface, initially contained two 150-megawatt turbine machines, with a third added in 1988. Remotely controlled from Hobart, the station could be accessed via a lift or a tunnel from the Gordon Road.

Strathgordon village was established in the 1960s to accommodate the workforce during the dam’s construction, transforming from a construction camp into a community with modern facilities. All the buildings were prefabricated in an on-site factory.

It was some time before residents became accustomed to the high annual rainfall of four metres and the long drive of 140 kilometres to Hobart. The eventual sealing of the road made the journey less of a trial.

Operation of the dam

Water from the lake falls down the intake tunnel about 12 metres in diameter and 137 metres from the bottom of the lake down to this power funnel and then runs 140 metres to the machines in the power station. Each machine needs 90,000 litres of water per second to spin and generate electricity. The water goes through the tail race tunnel back into the Gordon River, then Strahan and Macquarie Harbour. The generated electricity comes up the lift shaft through big conductors and is then sent to Hobart.

It wasn’t until October 1977 the first generator was commissioned.

Environmental Debate

Despite its engineering marvel, the Gordon Dam project sparked significant environmental controversy, particularly concerning the flooding of Lake Pedder. The original and natural Lake Pedder was a remnant glacial lake flanked by a spectacular, pink quartzite beach and mossy rivulets.

Therefore, it was no surprise that a small conservation movement vehemently opposed the flooding of Lake Pedder. In March 1972, a meeting was held in the Hobart Town Hall to protest its flooding. One of the key participants was Richard Jones, who formed the United Tasmania Group, the first environmental political party in the country.

The original HEC submission to parliament recommended a Scenic Reserve to cover the enlarged Lake Pedder. A State Legislative Council Select Committee heard submissions from the public on the scheme, but the government introduced legislation authorising expenditure on the dam before the Committee completed its hearings.

Opposition also gathered traction on the mainland, and the controversy prompted federal government intervention which resulted in a Federal Lake Pedder Committee of Inquiry in 1973. The Federal Government proposed a moratorium on the scheme and offered to pay the costs, but the Tasmanian government rejected this.

The Lake Pedder Committee’s report was tabled in federal parliament in 1974. It analysed the perceived environmental impact of the Gordon Dam scheme and recommended a reaction to major natural resource projects. In response to the report, the federal government ratified the World Heritage Convention.

In 1980, when the HEC planned to build another big hydroelectric scheme and dam the Franklin River below Gordon, local environmentalists mounted a campaign to save Tasmania’s “last wild river”, which aroused the emotions of middle-class inner-city dwellers in the state’s capital cities.

The campaign won a World Heritage listing for the Franklin and the incoming Australian Labor government promised it would halt the power scheme. The HEC abandoned the scheme when the High Court found that the External Relations powers enjoyed by the Commonwealth under the Australian Constitution gave it the right to honour its international treaty obligations by preventing the flooding of the Franklin, notwithstanding Tasmania’s constitutional land use rights.

There have been calls recently to restore Lake Pedder back to its natural state by throwing millions of dollars at a remediation project. However, it is an unaffordable fantasy.

Lake Pedder supplies 42 per cent of the water inflows to the Gordon Scheme. It provides about 515 gigawatt hours of renewable hydropower each year. It is part of HEC’s only two storages that have multi-year storage capacity and is critical for managing variable inflows from year to year.

The dam today

Today, the Gordon Dam remains a testament to human ingenuity and determination. It continues to generate significant hydroelectric power, contributing about 25 percent of Tasmania’s electricity and serving as a crucial water storage during droughts. However, earlier this year, without the added boost from the Franklin-below-Gordon scheme, the Tasmanian government was forced to fire up its biggest gas fired power generator for the first time in five years as an extended dry period the previous summer and autumn put pressure on the state’s hydro resources.

The area has become a popular tourist destination, with the Strathgordon village now functioning as a wilderness lodge, attracting visitors with its blend of natural beauty and engineering prowess.

Fifty years old this month, and despite ongoing debates about its environmental impact, the Gordon Dam stands as a symbol of Tasmania’s pioneering spirit in renewable energy development.

Another informative content quilling Robert.

It’s a pity that Principal Design Engineer Dr Sergio Giudici or an equivalent genius is not available to help Snowy 2.100000 emerge from its dark hole.

Gary

This post is written in a one-sided, revisionist way by Robert Onfray: “transformed a remote wilderness into a powerhouse of renewable energy”. This history is not so simple as we all know.

It dammed Lake Pedder, which was also so short-sighted and destructive that it led to the world’s first parliamentary green movement.

Perhaps its real significance is Tasmania’s contribution to the National and Global Environmental Movement. One could also argue that Tasmania has been transformed into a prosperous, educated, and creative place of opportunity for a much more diverse population. Think of MONA, strong whiskey, good cheese, bushwalking, and a growing population and place of investment.

Sure, Old Tasmania built the foundations, but let’s put that awful conflicted past behind us. 21st C Tasmania is a fabulous place, progress takes many forms.

Ah, the “let’s bury the past and toast to MONA and whiskey” argument.

While I agree Tasmania today is a vibrant and diverse place, this perspective conveniently sidesteps the foundation upon which that prosperity rests—built, quite literally, on the hard-won achievements of projects like the Gordon Dam.

Progress takes many forms, indeed, but it rarely comes from ignoring history or labelling it “awful.”

The claim that this is “revisionist” is rich. The post acknowledges the environmental controversy surrounding Lake Pedder—no whitewashing there. But reducing the dam’s legacy to a “short-sighted and destructive” act ignores its role as a cornerstone of Tasmania’s renewable energy infrastructure, delivering clean power that supports the very modern lifestyle you celebrate. Without it, Tasmania’s “place of investment” might look quite different.

Yes, the environmental movement born of Lake Pedder is globally significant. But doesn’t that demonstrate how complex legacies can drive both ecological consciousness and technical innovation? It’s not either-or; it’s both.

As for “conflicted pasts,” every era has its compromises. MONA, cheese, and whiskey are lovely, but let’s not forget they flourish in a state powered by renewable energy, where infrastructure like the Gordon Dam remains essential. Progress takes many forms—but dismissing the hard, messy work that enables it doesn’t help anyone.

Cheers to complexity, not erasure.

Robert, a very well-written article. As always you acknowledge both sides of the story.