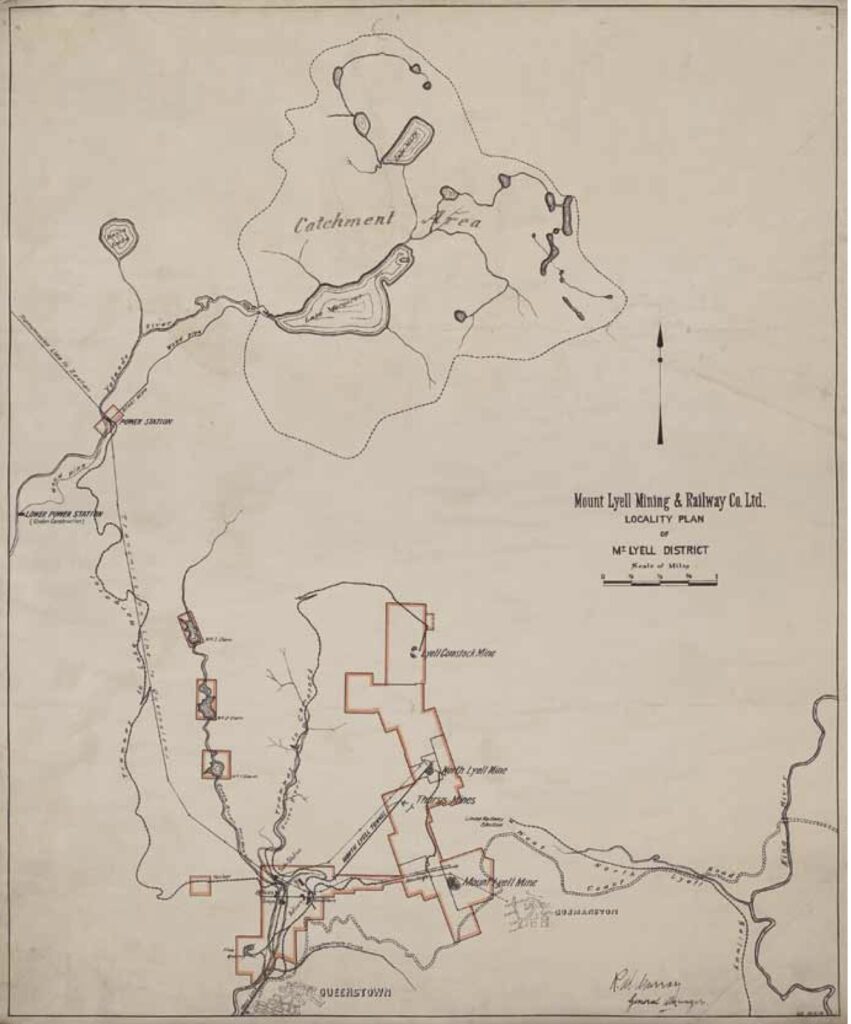

It all started in November 1883. Payable gold was found on a high ridge separating the magical Linda Valley from the Queen River valley, some 18 kilometres inland from the isolated west coast Tasmanian town of Strahan. This discovery led to mining leases that supported rich copper mines. These mines eventually merged in 1903 to form Mount Lyell’s, and indeed the world’s, largest copper mining operations.

The ground-breaking pyritic smelting of copper ore and the mine shafts had an insatiable demand for timber sourced from the dense rainforest stands that clothed the surrounding mountain slopes. The slopes quickly became denuded of timber, and the toxic sulphur fumes from the smelter stack killed off any regrowth.

In 1908, 1,200 tons of wood a week were being cut by 140 firewood getters, stripping the forests bare for up to six miles from the mine. Three years later, the cost of cutting and transporting firewood had risen dramatically as wood sourcing occurred further away in rugged and remote areas.

By this time, using hydroelectric power and utilising the rivers and lakes in the very wet region became desirable. The manager of the Mount Lyell Mine, Robert Sticht, had previous experience with hydroelectric power while working in America. He firmly believed at least £50,000 per year could be saved in fuel costs if they utilised hydroelectric power.

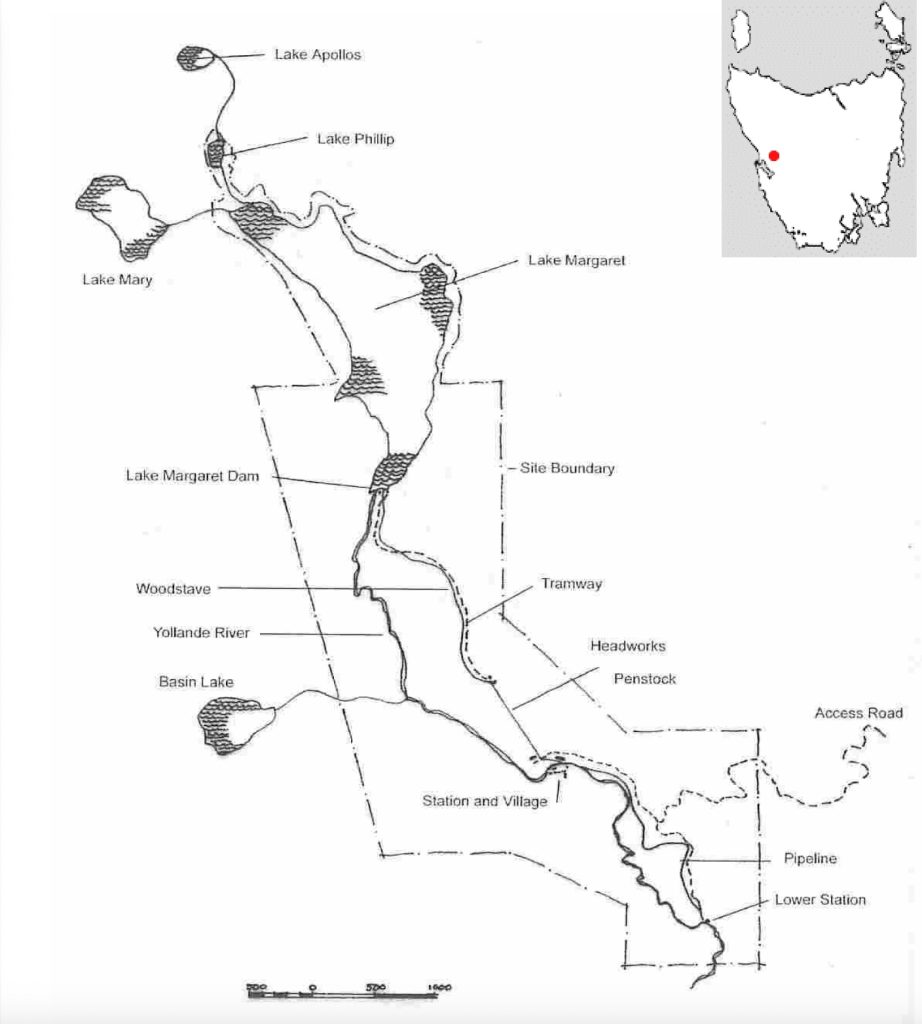

Only five miles from the smelters was the naturally occurring glacial lake called Lake Margaret, high up on the flank of Mount Sedgwick. Despite its small catchment area, it had an average rainfall of 3.68 metres a year, making it an ideal water storage proposition.

A hydroelectric scheme was approved in 1912 with a power station to be built beside the Yolande River. This stream formed a natural overflow from Lake Margaret. A wood stave pipeline was constructed to harness the water flow.

It was decided to use timber for the pipeline in favour of stainless steel because the latter is surprisingly not strong enough, particularly on curved pipelines, and requires thrust blocks. Additionally, the steel is prone to rust in the West Coast conditions. Also, wood is a natural insulator, preventing water from freezing in winter.

Wooden pipelines were fairly common at the time, seen as a solution for transporting water, particularly in remote or developing areas. These pipelines were constructed from wooden staves, bound together with metal bands, and sealed to prevent leakage.

The Lake Margaret hydroelectric scheme was commissioned in November 1914 for £164,000. It was the largest privately developed hydroelectric power station in Australia at its time and arguably the forerunner of Tasmania’s large-scale publicly funded hydro development.

The pipeline

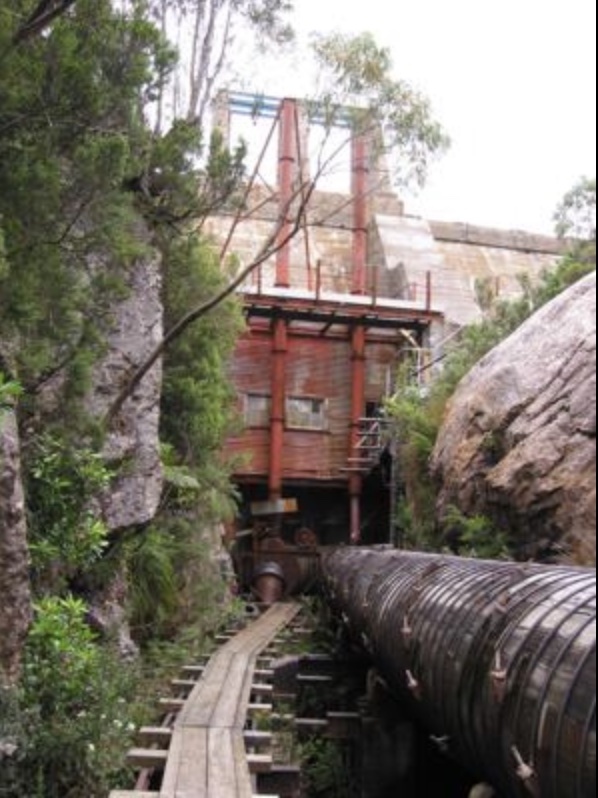

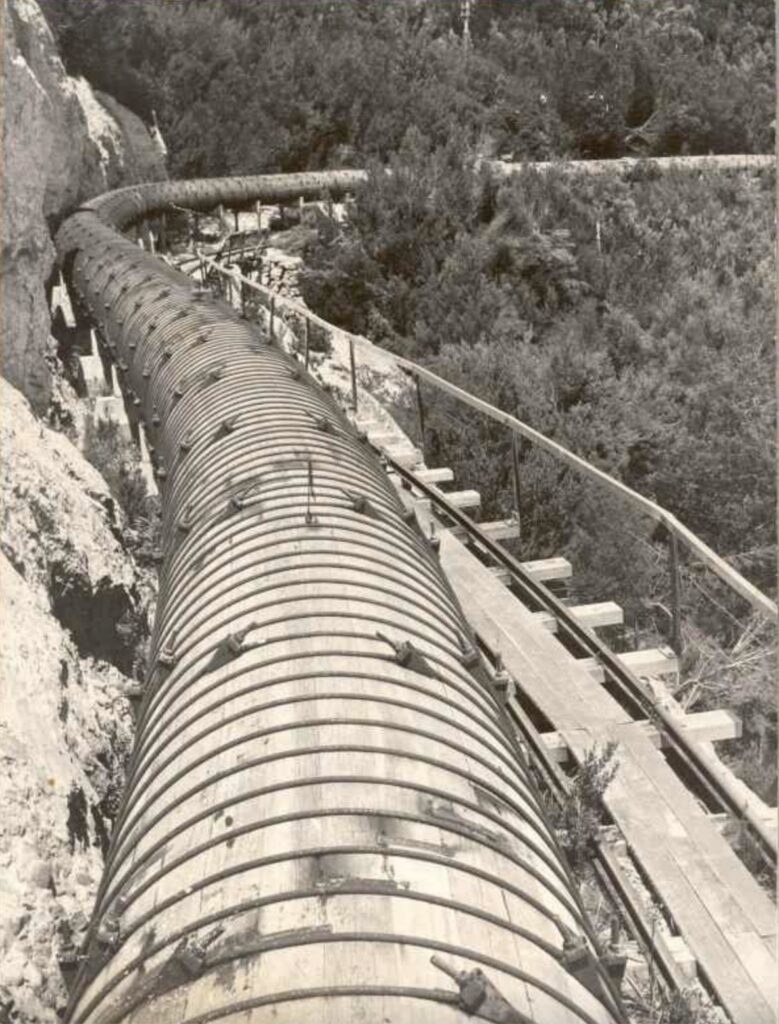

The centrepiece of the Lake Margaret Hydroelectric Power Scheme is a 2.2-kilometre pipeline made of wood staves. The lake end of the 48-inch pipeline was built into the natural rock construction, which backed up the water. Thus, no dam wall was necessary. It then fell 45 feet on an even gradient to the top of a penstock. A steel-railed tramway shadowed the pipe’s route for construction purposes.

The timber used to make the pipeline was Douglas fir imported from Canada, which was the cheapest option then. A special profiling tool machined the longitudinal edges of the staves to the required angle so they fitted snugly together in a circular shape. Each length of pipe was bound by circular metal hoops or bands, spaced several inches apart, and screw-tightened to bind the staves together to make the pipe watertight. The design concept is like a cooper’s barrel.

A nearby surge pipe was constructed of King Billy pine, which was locally abundant. It was built in the same way as the wood stave pipe as an experiment to test its longevity should it be required in the future.

There were many problems with leakage from the Douglas fir pipeline. After intensive maintenance requirements, it was decided in 1937 to replace the wood staves. Because the King Billy pine had performed well, it was chosen as the replacement timber despite concerns over its suitability and untested nature.

King Billy pine

King Billy pine is a relatively rare softwood only found in cold and sub-alpine forests of the west coast of Tasmania.

It possesses a beautiful straight grain, which makes it is easy to work on. It is a popular specialty timber species used in various applications such as boat building, furniture, sculptures, and musical instruments.

During World War I, the Dunkley Brothers sawmill at Zeehan cut King Billy pine into tent poles for the Defence Department and made broom handles. They sourced their timber from the slopes of Mt Black and other localities around Rosebery.

In the 1930s, when the highly favoured Huon pine was no longer available, King Billy pine took its place. It became a prominent part of Tasmanian houses built in that decade, mainly used for sash windows and verandah posts.

Wood stave pipelines are made in other parts of the world, such as the USA, Canada, South Africa and the Caribbean. Usually, these pipelines have a life span of between 40 and 50 years. Remarkably, the King Billy pipeline lasted for 69 years.

Closure and demolition

The Hydro Electric Commission (HEC) took over the Lake Margaret Power Station in 1985. In December 1994, the Lower Power Station ceased generating.

In December 2005, Hydro Tasmania[i] decided to shut down the Upper Power Station due to concerns about the safety of the wood stave pipeline. At least ten per cent of water was lost through leakage in the form of spectacular waterspouts at regular intervals along the pipeline. The pipeline failed principally from the freeze/thaw action on the upper surface, leading to persistent but prolonged internal erosion from fungal attack.

Later studies on the aging asset showed the timber thickness had reduced from 48 millimetres to an average thickness of 29.6 millimetres. Ice, wind, ultraviolet light and the passage of water internally had worn the wood into a more fibrous state. Essentially, the pipe was at the end of its serviceable life, and engineers believed it posed a great risk of failure.

However, from 2005 to 2007, there were efforts to try and consider other options to maintain the site rather than a single focus on an immediate shutdown due to safety concerns. Removing the wooden pipeline was seen as a major departure from recognising important heritage values.

The West Coast Council refused the development application to remove the pipeline based on advice from Heritage Tasmania. A bitter fight within government bureaucracies added to the drama.

A rebirth of sorts

In November 2006, Hydro Tasmania released a feasibility study to redevelop Lake Margaret. All its options involved replacing the pipeline with another wood stave pipeline. Economics dictated that timber was the preferred material over steel or fibreglass. Work commenced in September 2008, demolishing the King Billy pipeline and replacing it with Alaskan yellow cedar, known for its durability.

Usually, creosote-treated Douglas fir is used, but this option was not acceptable to Hydro Tasmania. However, Alaskan yellow cedar is easily obtainable and considerably cheaper than the only other timber alternative, Californian redwood. Sadly, no Australian timber could be used, not only because we don’t have many species possessing the qualities necessary to shape into a pipeline easily, but because of our new-found propensity to lock up our native forests and restrict their use.

About 300,000 lineal feet of Alaskan yellow cedar, in 24 shipping containers, were imported. The kiln-dried staves averaged 13 feet long, and the longitudinal edges were profiled as tongue-in-groove. Forty-three staves make up the pipe diameter of four feet. About 22,000 steel bands tightly bind the staves together along the whole length of the pipeline. The new pipeline was built under the supervision of a wood stave expert from the Canadian International Tank and Pipe Company.

The King Billy pine was stockpiled and planned to be disposed of through tender after tests for contaminants and timber preservatives. The new 21-metre bar overlooking the lake at the Pedder Wilderness Lodge is believed to contain King Billy pine from the pipeline.

As a tribute to its long life, three short sections of the original King Billy pine pipeline have been preserved by reinforcing the wood internally and bracing the steel supports on the tall sections.

It will be interesting to see how the imported American substitute compares with the native Tasmanian timber over time.

[I] In 1998 HEC was disaggregated into generation, transmission and retail businesses and became a vastly different organisation to that of its heyday building major dams. However, people still saw it as the same organisation it was 30 years ago, possessing the finances and the expertise to upgrading the Lake Margaret Power Scheme.

Great pics and story. I have shared with family members who now work at Hydro.

Great story Robert. I think there is a typo where 2014 was date of commissioning Lake Mary HE scheme for 165,00 pounds.

Excellent pick up Dixie. No matter how many times I reread it before publishing, I kept overlooking that mistake! All corrected now.

I found this a very interesting read, especially about wooden pipelines. I wonder if the rum barrels on the old schooners helped them to decide on wooden rounded pipes.

Great photos helped me to visually imagine the pipes and surrounds.

Thanks Robert.

Another detailed story, Rob. Thanks.

I would have thought “tongue-and-groove” would have made the water pipeline staves much more waterproof and prevented sideways buckling as the hoops were tightened.

Was hoop pine from Queensland, with its long knot-free lengths, straight grain and durability considered, instead of imported Alaskan yellow cedar?

In the 19th and 20th century, hoop pine was extensively used as 6″x 1″ boards for durable flooring in “Queenslander” homes and many of these homes, over 100 years old, still contain perfect timber. This species was also extensively used as moulded “tongue-and-groove” wall and ceiling cladding before the popularisation of plastering.

Great question Alan and good points. Unfortunately, I can’t provide an answer.

I would hope that Australian native timber options were given high priority before deciding on using the imported Alaskan yellow cedar. However, I am not confident that was the case for political reasons and because the option of using Australian native timber was, sadly, just too expensive.

What was the internal reinforcing and how was it installed?

Jenny

I cover both questions in my story.

Essentially, no reinforcing because as I wrote for the King Billy pine: “the timber thickness had reduced from 48 millimetres to an average thickness of 29.6 millimetres. Ice, wind, ultraviolet light and the passage of water internally had worn the wood into a more fibrous state”.

As for how it was built, I provide details when it was first constructed using douglas fir:

“A special profiling tool machined the longitudinal edges of the staves to the required angle so they fitted snugly together in a circular shape. Each length of pipe was bound by circular metal hoops or bands, spaced several inches apart, and screw-tightened to bind the staves together to make the pipe watertight. The design concept is like a cooper’s barrel”.