It began as a deep distant rumbling, like the stirring of some gargantuan subterranean beast.

It was unsettling at first, ominous, something you felt in your guts more than you heard with your ears, an eerie subsonic vibration that seemed to rise from the bowels of Hades.

As the she-devil crept closer, the wailing began.

The guttural groan became more and more intense as the pitch began to rise, building in intensity until the wailing became a banshee scream.

Suddenly the inky blackness of the night was split with vibrant flashes of dazzling lightning as the beast leapt upon us.

The noise was unfathomable as the building was ripped asunder, like the screams of a legion of tormented souls, riding a thousand ear splitting locomotives down into the depths of Hell.

Tracy had arrived.

Twelve-year-old Shane Stringer survived Cyclone Tracy. His family sheltered in their Ludmilla home when the cyclone hit. As the house disintegrated, his parents wore motorcycle helmets, and the kids wore construction helmets. They were all tied together and dashed past flying debris to their neighbour’s brick home. His mother had the foresight to turn over a couch and table to protect the children seconds before a glass sliding door exploded and sent glass shrapnel across the room.

Cyclone Tracy remains a tragic example of how a destructive event caused so much socio-economic hardship to an isolated city. While the damage couldn’t be avoided, the death toll may have been reduced by responding adequately to the timely cyclone warnings if the city had houses with in-built or adequate public shelters.

Darwin’s population was around 47,000 then, and some 10,000 were away elsewhere during their Christmas holidays.

Darwin’s tropical climate is not immune to cyclones. During its short history of European settlement, the city witnessed major cyclones in 1878, 1897, 1917 and 1937. The 1974-75 cyclone season started in early December with cyclone Selma, which approached Darwin but suddenly veered away when only 50 kilometres away and travelled over Bathurst Island. Darwin suffered strong winds but very little or no damage.

This pattern was not unusual. In the previous decade, there were 25 major named cyclones, none striking the city. Many locals believed cyclones missed Darwin. The last cyclone in 1937 was so long ago that few people living in Darwin at the time believed Darwin was exposed to any destructive cyclones.

False alarms were standard, and the media highlighted what they believed was few residents paying attention to the radio warnings. When danger fails to appear, people tend to become sceptical and complacent. Darwin wasn’t immune to this as it developed a reputation that cyclones avoid Darwin.

One resident summed up possibly the feelings at the time:

“We had had Cyclone Selma only a few weeks before … Everyone was sick of talking about cyclones – and besides, Christmas was here”.

The media tended to drum up this story of complacency prevalent in late December 1974 and helped contribute to the outcomes of the cyclone. However, survivors deny they were indifferent and didn’t prepare. Former ABC journalist Richard Creswick, who was in Darwin at the time, revealed that the head of the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), Ray Wilkie asked him:

Not to over-dramatise it. Don’t scare the population. And we were being told until quite late that Cyclone Tracy would pass to the north of Darwin across Shoal Bay at five o’clock in the morning. That was the message that I put to air. And then everybody went out and partied.

Nonetheless, trucks that drove through the city streets on Christmas Eve had speakers broadcasting emergency alerts. Some residents put masking tape on windows, tied down loose objects and had a battery torch and transistor radio ready. However, they strongly argued that no one had advised them about the actual intensity of what was approaching, and they felt helpless when their houses, their only shelter, had disintegrated around them.

Development of the cyclone

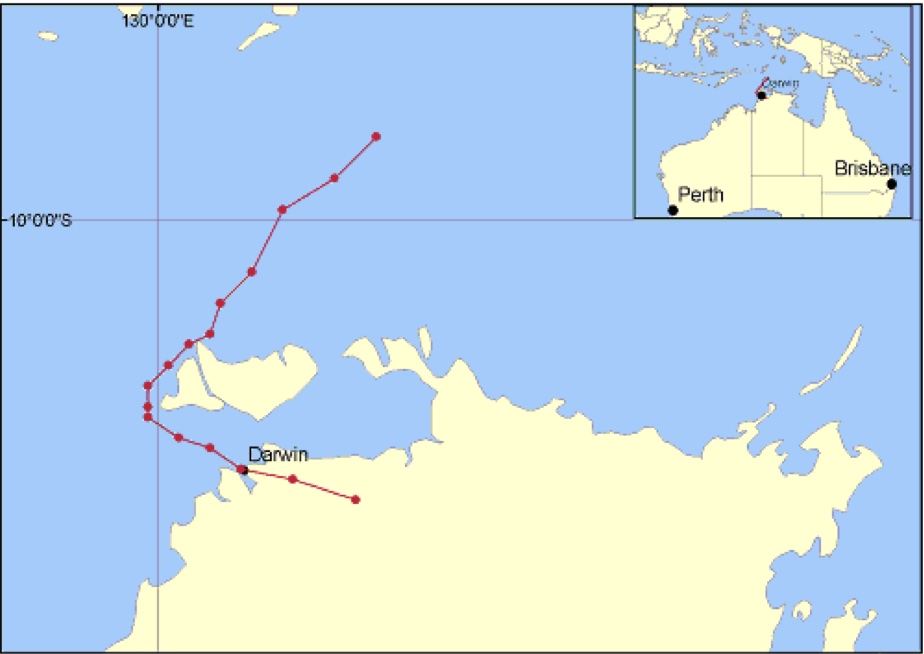

Cyclone Tracy originated as a weak tropical low about 700 kilometres north-east of Darwin on 20 December 1974. As it moved south-west towards Darwin, the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) monitored the slow build-up of the low using USA meteorological satellites. While the technology was not the same nor as frequent as today, they managed to track its path accurately in the early stages .

The next day, the low intensified rapidly and formed a cyclone named Tracy. It was now only about 220 kilometres from Darwin. However, it virtually stopped moving and sat where it was. It was a small storm, able to fit entirely within the 40-mile wedge between Bathurst Island and the mainland. It spun meekly, ever so slowly to the south-west.

Early on Christmas Eve, the situation changed dramatically. Tracy changed direction, moved around the south-west corner of Bathurst Island, and then abruptly, for reasons still unknown, turned 90 degrees and headed towards Darwin.

At 12:30 pm, the BOM issued Warning No. 16, which alerted people to the change in direction, finally forecasting “very destructive winds in the Darwin area tonight and tomorrow”. Warnings began hourly on the ABC radio. Don Sanders was the broadcaster with a rich and soothing voice. He told people to check their transistor radios and spare batteries, batten down their houses, remove pictures from the walls, pack away loose items on tables, and prepare to shelter under beds or tables and fill the bath with water.

The problem was that in every wet season, the warnings were frequent. Most of the time, people could afford to ignore them and get on with their lives. People went to bed, some drunk from Christmas parties, without knowing the nightmare that was about to descend on them.

The cyclone was still tiny and remained so, now only seven miles in width. Winds were over 60 kilometres an hour, extending only 30 miles from the storm’s centre, and cyclone-force winds extending less than eight miles. It was one of the smallest tropical cyclones ever recorded.

However, unbeknownst to meteorologists tracking it, the storm developed much stronger winds than initially estimated. The situation deteriorated rapidly when the storm approached the mainland as darkness fell over Darwin. The cyclone entered a period of “explosive deepening” just before landfall, and it gained intensity. The storm’s eye was contracted to only five miles wide and passed directly over Darwin.

Winds picked up shortly after 11 pm as a few partygoers left the pubs and office parties and headed home.

At its height, its eye was 12 kilometres wide, and the winds spiralled out for about 40 kilometres. In comparison, Hurricane Katrina was 644 kilometres wide when it made landfall in 2005. Tracy moved slowly, very slowly, which was one reason for its destructive force. Cyclonic force winds belted Darwin for more than three hours. The other reason was the steep pressure gradient of the cyclone. The cyclone’s small size compressed the pressure difference into a tiny area, which happened to be over a city of 40,000 plus residents.

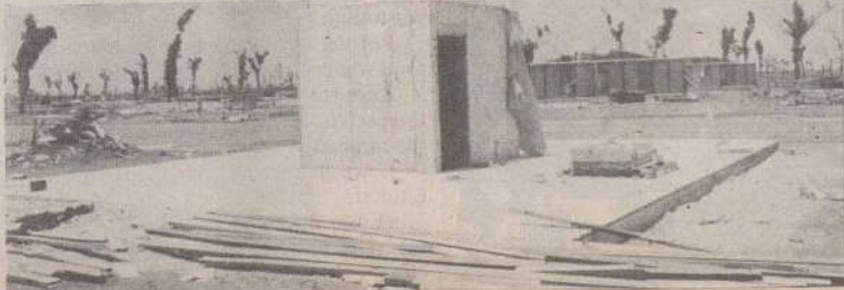

The extensive structural damage Cyclone Tracy inflicted on Darwin made it legendary in Australian natural disaster folklore. In the northern suburbs, nearly 100 per cent of the houses were ruined.

Tracy wipes out a city

“What happened to Darwin on Christmas morning has never happened in Australia before. Darwin is devastated. Darwin is destroyed. Darwin looks like a battlefield.”

Acting PM Dr Jim Cairns

The community’s reactions to these warnings were reported as being complacent. Office Christmas Eve parties still went ahead, pubs were full, and people even attended midnight mass at St Mary’s Cathedral, all of which delayed any meaningful reaction.

There were considerable instructions through the media of the precautions to take and most of the population took note of them, once they realised the seriousness of the cyclone.

At Category 3, the cyclone was not considered a significant threat, especially to the marine fleet. Patrol boats and other vessels were taken into Darwin Harbour to prepare “for a bit of a blow”. Just enough to put a bit of a dampener on the Christmas cheer.

However, things worsened around 2:30 am on Christmas morning, immediately after BOM issued the last forecast warning. Tracy began to move slowly across Darwin, producing sustained winds of over 200 kilometres an hour for several hours. Power failed around 3:30 am.

The cyclone forced residents to huddle in terror in their houses as they were ripped apart. Debris from thousands of disintegrating houses flew around them, banging loudly against the flimsy sides of their homes, providing the only shelter they could find. The shrieking wind gusts, the pelting rain and the darkness added to the occasion. The terrified residents quickly realised their lives were in danger.

At 4 am, the eye of the cyclone passed over. Many residents thought the ordeal was over and the cyclone had passed. But not long after, the winds returned from the other direction with equal ferocity. Structures still standing copped the brunt. Researchers later believed that the “decreased fetch roughness” at the back of the storm’s eyewall probably increased intensity in the badly affected northern suburbs, where most of the fatalities were.

At the first uncertain light of dawn, Tracy finally started to move south eastwards across Arnhem Land. It petered out over the Gulf of Carpentaria in Queensland a week later.

The descriptions from people who survived reveal just how terrifying the cyclone was. The common theme was the noise of the wind. Some described hearing roofs ripped off nearby buildings:

as though they were made of paper.

Another described it:

was like bombs going off.

Conditions moderated around dawn on Christmas Day, and residents gradually emerged from their hideaways to see the devastation. Many described the scene as “like an atom bomb had hit the place”. The officer commanding the Darwin RAAF base, Group Captain Hitchins, who was in Japan after the Americans dropped the nuclear bombs, likened the appearance of Darwin to Hiroshima.

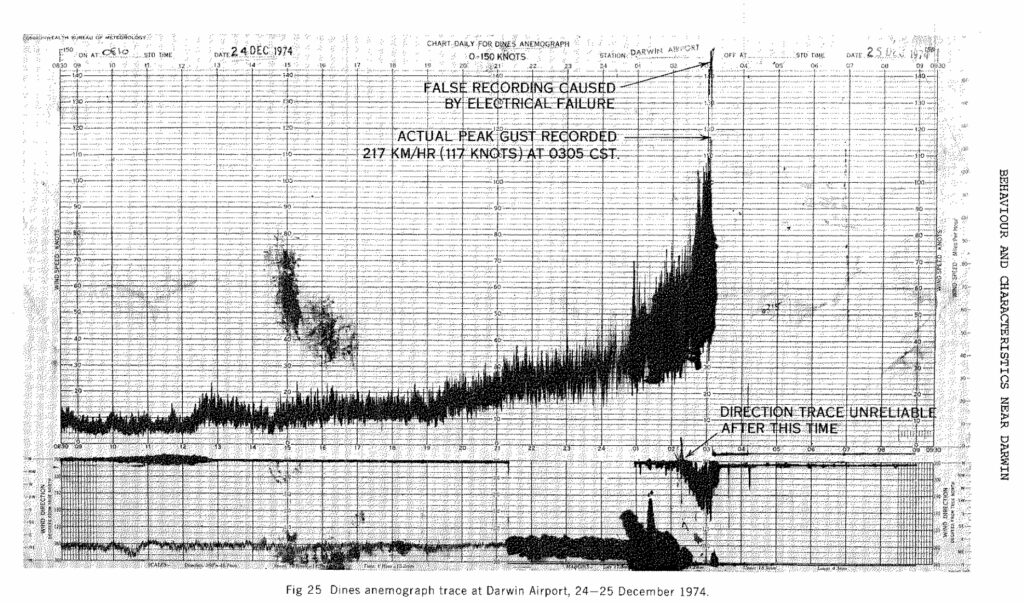

The official wind instrument recordings at the airport show the wind reaching a peak gust of 217 kilometres an hour at about 3 am. However, the anemograph was damaged and stopped operating shortly afterwards. There was also 255 millimetres of overnight rain, which compounded the damage. A storm surge reached 1.6 metres in the city harbour and 4 metres at Casuarina Beach to the east of Darwin.

Many survivors recall their surprise seeing the sea from their homes when they emerged from their wrecked houses because the intervening vegetation and houses were destroyed.

After the turmoil

The streets resembled battle zones. There was no power, no water, no food, nothing. Most of the buildings were destroyed or badly damaged. Seventy-five people died, either killed in the city or drowned at sea. Hundreds were injured, 75 per cent of the 12,000 homes were destroyed, and only about 500 homes were habitable. People were left sitting on bare floorboards or the concrete storage sheds under the piers or were trapped. Rescuers found a 73-year-old woman trapped in her home four days after the cyclone.

Every single public building was destroyed or seriously damaged. Windows blew in, parts of the roof blew off, steam pipes burst, and oxygen supply pipes were damaged at the hospital, almost paralysing the hospital services. Survivors found aeroplanes at the Darwin airport lying on their backs, and the hangars, built in World War II, had crumbled. The wild winds flattened the control tower and the communications facilities at the nearby army base.

On Christmas morning, Darwinians felt isolated and alone. They were worried that the rest of the country didn’t know and were enjoying their Christmas, unaware the cyclone had them wiped out. All communications were offline. The ABC managed to use a ship’s radio to get a message out – “Darwin devastated by cyclone … Anticipated up to 35,000 evacuees”. Authorities first heard the news at 6:20 am when the Cyclone Tropical Warning Centre in Perth called the National Disasters Organisation in Canberra. ABC footage, shot early on Christmas Day by Keith Bushnell, was seen by a shocked nation late on Boxing Day.

A lot of the people still in the city fell to pieces. The cyclone didn’t just destroy their lives and houses but also their way of living and their spirit. Some claim it made people psychotic. Many were in shock at the level of devastation.

Officials listed those not known to be dead as missing. Initially, the only persons considered missing were those believed from the boats in the harbour and whose bodies authorities never found. About 160 people were listed as missing as late as 1981, after which they were finally declared dead.

There were rumours that ‘thousands of bodies” were under the wreckage in the northern suburbs, mass graves dug, and bodies buried. It was, in part, fuelled by scepticism of the low official death toll. Darwin is not immune to so-called cover-ups. Locals believed that the government was evasive about the number of people who died during the Japanese bombing raids in 1942. Many soldiers claimed they dug graves for hundreds of bodies. In 2012, author Roland Perry wrote:

“As many as 1,100 people may have died in the [initial] bombing – and were buried in mass graves at Mindil Beach”.

There was also difficulty confirming the deaths at sea. At least 29 boats were sunk or wrecked, several driven ashore, and at least 20 people lost. Two weeks after the cyclone, 13 ships were still missing, and 20 people were unaccounted for in Darwin Harbour. Amazingly, people didn’t find ferries such as Mandorah Queen until 1981 and Darwin Princess in 2004.

The damage bill at the time was between $800 million and $1.3 billion, the equivalent of up to $12 billion today, making it one of the world’s most costly disasters.

A major wet season occurred the summer before Tracy, cutting off Darwin for almost three months; there were significant floods elsewhere in the country; nearly every river in Queensland flooded; and on Australia Day, Brisbane saw one of its worst flooding events. The Northern Territory decided to develop a comprehensive plan after that wet season. The first-ever Disaster Plan was approved just 20 days before Cyclone Tracy.

It was clear an evacuation before the cyclone was not a priority, based on the ABC broadcast on Christmas Eve, which advised residents to take shelter in their homes. Equally, given the difficulties faced afterwards, it is problematic that an adequate evacuation of so many people could have occurred prior to the cyclone anyway.

In the days after the cyclone, the federal government dispatched the armed forces, engineers, and other specialists to help ensure Darwin had the basic requirements for survival.

A large percentage of the population, about 30,000, were stranded in the city. Government officials required drastic measures to deal with the problem immediately. There was no running water, sanitation, electricity, little shelter and a high risk of disease outbreaks such as typhoid and cholera.

Officials quickly evacuated the non-essential people to southern states the week after the cyclone. A giant American Starlifter joined the air force in bringing much-needed supplies and taking out evacuees. Many of those people never returned. It remains Australia’s most extensive peacetime civilian evacuation program. On one day, more than 40 military flights left Darwin. In total, they airlifted over 25,000 people.

Those who could fire up their cars, about another 7,000 people, drove out of the city south to Alice Springs. One thousand battered cars arrived in Alice over the next three days. In total, about 15,000 people never returned.

While the evacuation process over five days was generally lauded as a successful campaign, as with any emergency, it was beset with many problems. The major one at the outset was communications. There was no radio, telephone, or other medium other than sending messages on scraps of paper via a runner and receiving a hand-written response. It took time to locate a person at Casuarina or Nightcliff.

Quite often, the planes used to evacuate so many people were military setups that were not intended for passengers. They were uncomfortable, had little seating, no catering and no toilets. Many were strapped to the floor. One big commercial plane, configured for 365 passengers, had 715 people on board. In the frantic rush to get people out, many did not end up in the states they had relatives to call upon. Nearly half the population of Darwin ended up scattered around Australia.

Armed personnel and emergency workers were called back from leave. Relief agencies set up depots and kitchens along the road and the airport to greet evacuees. By New Year’s Eve, only 10,638 people remained in Darwin.

Not everyone agreed with the decision to evacuate. Some believed the mistakes made during the bombing of Darwin were made again after the cyclone. The wartime evacuation in ramshackle boats was crude and shambolic, particularly for the women and children. Many believed that the primary concern for the evacuation – disease and starvation – were exaggerated.

However, the men dealing with the situation believed the criticisms were ill-informed and came not from the locals but from academics from outside the Territory.

The wind debate

“Cyclone Tracy blew away a way of life.”

Officially, Tracy was a Category 3 cyclone, meaning sustained winds were between 160 and 197 kilometres an hour. Debate still rages over the strength of the winds. Almost all the survivor accounts refer to the horrific noise of the wind. Many say the noise was unimaginable and very frightening. A cyclone has a sound, and it isn’t just the wind. It is the sound of hundreds and hundreds of sheets of flying corrugated iron scraped across the ground by the cyclonic winds.

The wind measuring instrument at Darwin Airport, called a Dines anemograph, was a particular model that was able to measure strong wind gusts every 2 to 3 seconds. It showed that sustained winds were rapidly intensifying when it failed at 3:10 am shortly before roof blew off the building at the airport.

The records report Cyclone Tracy had peak gusts of 213 kilometres an hour. This makes Tracy a Category 4 cyclone. In his report, Dr George Walker believed it wasn’t unreasonable to postulate the maximum gusts may been as high as 250-270 kilometres an hour in the northern suburbs.

However, unofficial estimates put the gusts as high as 300 kilometres an hour based on satellite and damage observations. BOM says the “apparent record of stronger winds was due to an electrical failure, and apart from this isolated record greater than 217 kilometres an hour, the wind speed record was reliable to be within about five kilometres an hour”.

When Major-General Alan Stretton addressed the crowd waiting at the airport to be evacuated, he mentioned they had been through wind speeds as high as 300 kilometres an hour. Many believe he didn’t make that up.

BOM concedes the area north of the anemometer site, which suffered the worst damage in the cyclone, “probably experienced the strongest winds in the cyclone before and after the passage of the eye”.

Unfortunately, the uncertainty over actual wind speeds is a common phenomenon following all major cyclonic events as the only reliable records are from anemometers, which usually fail because they are not designed for extreme wind speeds or are damaged by flying debris.

The rebuild

“There were little kids coming out literally from under the wreckage like little mice and cockroaches grasping stuff Santa had left”.

So reported Mike Hayes, a journalist, who drove through what was left of Darwin on Christmas morning.

The devastation was so bad the federal government considered abandoning the city and rebuilding somewhere else, such as Katherine. However, on his visit to the city after breaking off an overseas engagement in Europe, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam reassured residents that the government was determined to see the city rebuilt again. Indeed, Darwin developed quickly in the post-war years.

However, prior to the cyclone, there were no stringent cyclone building standards because not only had the city not experienced a severe cyclone for a few decades, there were no national building regulations. Building regulations were a state responsibility, and in the case of the Northern Territory, it rested with the Commonwealth government.

The main control over housing construction was via the lending authorities, especially the Commonwealth Bank who issued a “Blue Book” for builders. For northern Australia, their guidelines specified a minimum number of cyclone bolts from the top plate to the bottom plate, without any guidance on where they were to be placed. Rafters and trusses were fixed to the top plate by skew nails. Cyclone Tracy highlighted the weakness in this specification.

New suburban houses were built with the tropical heat in mind. They followed the design of Beni Burnett, the principal architect in the Northern Territory in the late 1930s and 40s.

His buildings were simple and maximised the airflow. They were elevated on top of cement pillars to take advantage of afternoon breezes and fitted with louvres for ventilation above partial external and a few internal walls. They were notorious for not blocking outside noise, and there was little privacy, but they were a godsend for surviving in the high-humidity weather.

However, even the newer modern homes built with cyclone standards in mind were ruined, although officials later realised they were not certified by a structural engineer.

Tracy’s strength was just too great to plan for. Cyclone Tracy tore down widely held beliefs about types of roof sheeting. Over 90 per cent of houses and 70 per cent of other buildings had their iron roofs torn off after only 15-20 minutes of winds, that were only up to 145 kilometres an hour, setting off a “chain reaction” of destruction.

Australia’s expert on cyclones at the time was Walker, the senior lecturer in engineering at James Cook University. He was on sabbatical leave in England when Tracy hit. At the request of the Commonwealth Department of Housing and Construction, he returned immediately to take a leading role in an investigation into the cyclone and its damage. Walker initiated the most extensive research into the cause of the structural failures. It led to some of the most stringent building codes in cyclone-exposed areas worldwide.

His investigative team found three main reasons for the damage: fatigue failures of cladding fasteners, internal pressures not allowed for in the design, and no secure fastening of wall cladding or internal wall linings to the house frame.

The need for the structural design of houses built in cyclone areas to be certified by engineers signalled higher costs and the fear of an end of the old “tropical living” designs. Walker also advocated the construction of a concrete central core that acted as a shelter inside the house to be used as a bathroom in normal times.

His recommendations that houses were to be designed to resist wind loads were regarded as radical at the time and were met with considerable hostility, particularly by engineers who considered it impossible to achieve.

Walker’s recommendations required a large amount of testing to determine the strength of traditional timber framed, lightly clad wall systems which is why the immediate reconstruction of houses in Darwin was not based on the traditional high set design.

However, once design criteria was established the high set “tropical living” designs again became popular, especially in North Queensland.

With the publication of the Building Code of Australia, now the National Construction Code, the requirement for houses to be structurally engineered for wind became a national regulation.

Many people who remained to pick up the pieces and rebuild their houses and lives struggled to get building materials to make their houses liveable in the short term. Many stories abound about how owners sat on their porches most of the day with a shotgun to stop raiders on their property. Houses left abandoned, or with no one in them, were targeted for roofing iron and other useful materials for rebuilding.

The Navy moved in to help with the clean-up. They brought in helicopters to help move the debris.

New Year’s Eve, a week after Tracy, signalled a symbolic end to the immediate emergency. While there still wasn’t running water (naked people had their showers under open fire hydrants on the Stuart Highway), people were fed, there were 200 emergency phone connections, postal services, bus services, and the weather bureau re-opened which helped relieve any anxiety about more cyclones arriving. Tradesmen gradually restored electricity. Most importantly, beer was back on sale, though the government applied limits.

On 28 February 1975, the Whitlam Government established the Darwin Reconstruction Commission to rebuild the city and they called in CSIRO to provide advice on new standards. The Commission rebuilt the city within three years, introducing new building codes later adopted across Australia.

By July 1975, the influx of newcomers – mainly reconstruction workers – raised the population to 33,000. Accommodation was provided by various means, including cruise liners, mobile dwellings and prefabricated units that were shipped in. As time passed, getting skilled staff for the building tasks was increasingly difficult. The government spent a lot of money attracting the workers and hosting their families.

Eighteen months after the cyclone, 44,000 people were living in Darwin again.

Stretton, the Director-General of the National Disasters Organisation, was appointed to head the relief effort. In his book, The Furious Days, he made sensational allegations of official mismanagement and authorities being “completely unprepared”. Many saw him as rather immodest in his abilities with a breath of fresh air. His obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald described his time in Darwin as a:

“Refreshing change to the obsessive secrecy of governments in crisis long endured by Australians. Disarmingly open, he held two daily press conferences, [and] was honest”.

The federal Liberal opposition party believed the disaster was above politics, and they fully cooperated with the government in rebuilding Darwin. While Whitlam returned to Australia as soon as he could, his political stocks dropped when he made a flying visit to Darwin and promptly resumed his overseas trip three days later, famously telling the head of the Prime Minister’s Department:

“Comrade, if I’m going to put up with the f––wits in the Labor Party, I’ve got to have my trips”.

Like every politician, he firmly believed that the disaster would enhance his standing. However, as history shows, ten months after the media and opposition mocked him for leaving the ruins of Darwin for those of Crete, he was dismissed from office.

Tracy changed Australia for the better. Destroying the old Darwin made the rest of the country more aware of the frontier city and the northern tropics. Whitlam declared three days after the cyclone the awakening of a new sense of community:

“It is an Australian tragedy which transcends politics, state boundaries and personal differences. Australians everywhere are responding spontaneously and generously to the call of help. Others likened the experience creating a national identity just like a foreign invasion has on other societies”.

Walker’s report, while replete with engineering and technical jargon, managed to sum up the whole Tracy disaster experience in the Australian context:

“It is unfortunate, but true, that one generally has to experience a disaster to be really convinced of the need to avoid one”.

We can take solace in the fact that the buildings in a resurrected Darwin City are now designed to meet what God throws at them. Let’s hope and pray they can withstand the next disaster.

A very good summary. I still can’t work out why more people were not killed given the large number of houses that were destroyed. J