Between 1967-75, Hobart endured a series of catastrophic events. It all started with the Black Tuesday fires in February 1967 that claimed 62 lives. Several other tragedies followed that to Hobartians, seemed like they would never end. August 1969 saw the disappearance of Lucille Butterworth, October 1973 the Blythe Star was wrecked off southern Tasmanian waters with three men drowning and seven survivors spending eight days adrift in a lifeboat, and the Mt St Canice boiler explosion in September 1974 that took eight lives. It culminated in the collapse of the Tasman Bridge on 5 January 1975. This disaster claimed 12 lives and severed Hobart’s critical link between its eastern suburbs and the city.

A tragedy that divided a city in two

On a quiet Sunday night, just before 9:30 pm, the bulk carrier Lake Illawarra, attempted to pass through the eastern span of the bridge, instead of the usual central navigational span, and collided with several of its pylons cutting it in two as it attempted to pass through the eastern span of the bridge rather than the central navigation span.

About a 127 metre section of the bridge deck collapsed onto the ship’s deck, sending it and seven crew members to the bottom of the Derwent River. Five motorists in four cars also perished as their vehicles plunged into the gap left by the collapsed roadway.

The destruction of the bridge cut off Hobart’s eastern shore. Suddenly, the city was in disarray as the only direct means of communication between the two halves of the city was lost leading to a complete disruption of personal, community and occupational life.

The first bridge

Plans to build a bridge over the Derwent River at Hobart date back to 1832, but it wasn’t until 1936 that definite plans were put forward. That year, Premier Albert Ogilvie announced legislation to enable a private company to construct a pontoon-style bridge, which would connect Hobart to its eastern suburbs. This major road link would operate as a toll bridge. After Ogilvie’s sudden death in 1939, it was revealed that the two largest shareholders in the company were his widow and a close friend.

The pontoon bridge itself was a pioneering design, the first of its kind globally. It consisted of 24 hollow pontoons, arranged in a crescent shape to form a two lane roadway, designed to withstand the river’s tidal forces. During construction, the two 12 pontoon sections were towed out into the river and connected to the banks and to each other in the middle via a large vertical locking pin. The bridge measured 961 metres in length and 12 metres in width, with a large lifting section at the western end to allow ships to pass through.

Opened in 1943 at a cost of half a million pounds, tolls were collected until 31 December 1948. The bridge became notorious for its eventful crossings, thanks to strong surges and the spray from breaking waves.

At the time, the eastern suburbs were largely residential, with few businesses or industries. Residents relied on the bridge to access services, workplaces and amenities on the western shore, such as hospitals, specialist doctors, education facilities, government services, entertainment and banks.

As the population expanded, so did traffic, causing the pontoon bridge to become congested. By 1955, traffic had reached 10,000 vehicles per day.

As early as 1952, a replacement bridge was discussed openly, but it wasn’t until 1956, that talk of a replacement began in earnest. A government-commissioned engineering report recommended a high-level, four-lane concrete bridge, which would allow ships to pass freely without traffic disruptions. The option was deemed only slightly more expensive than another low-level bridge.

The Tasman bridge

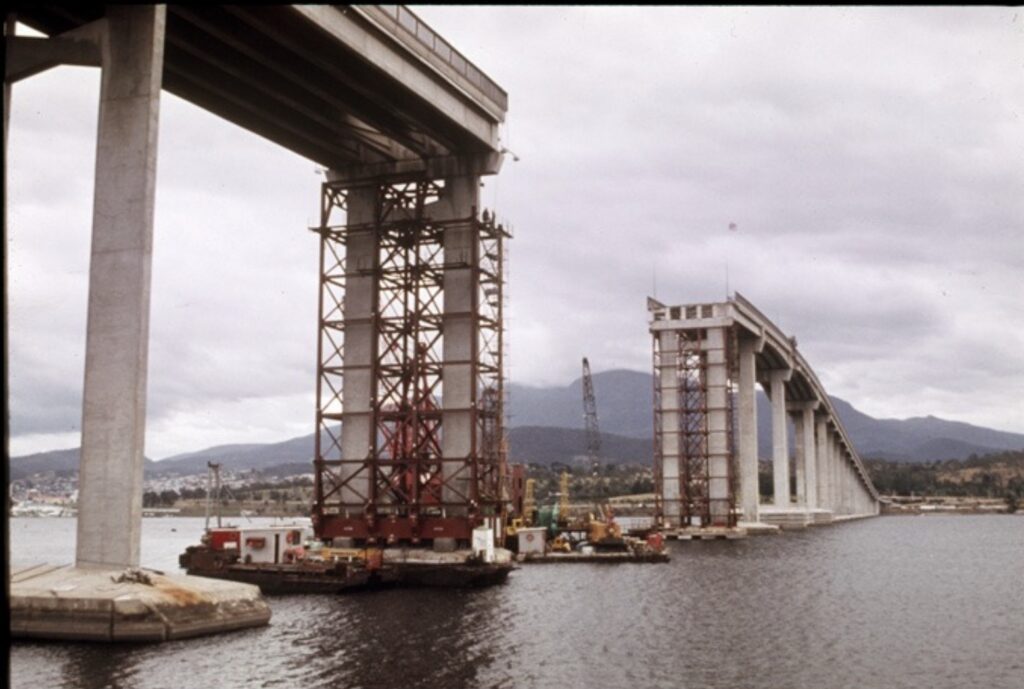

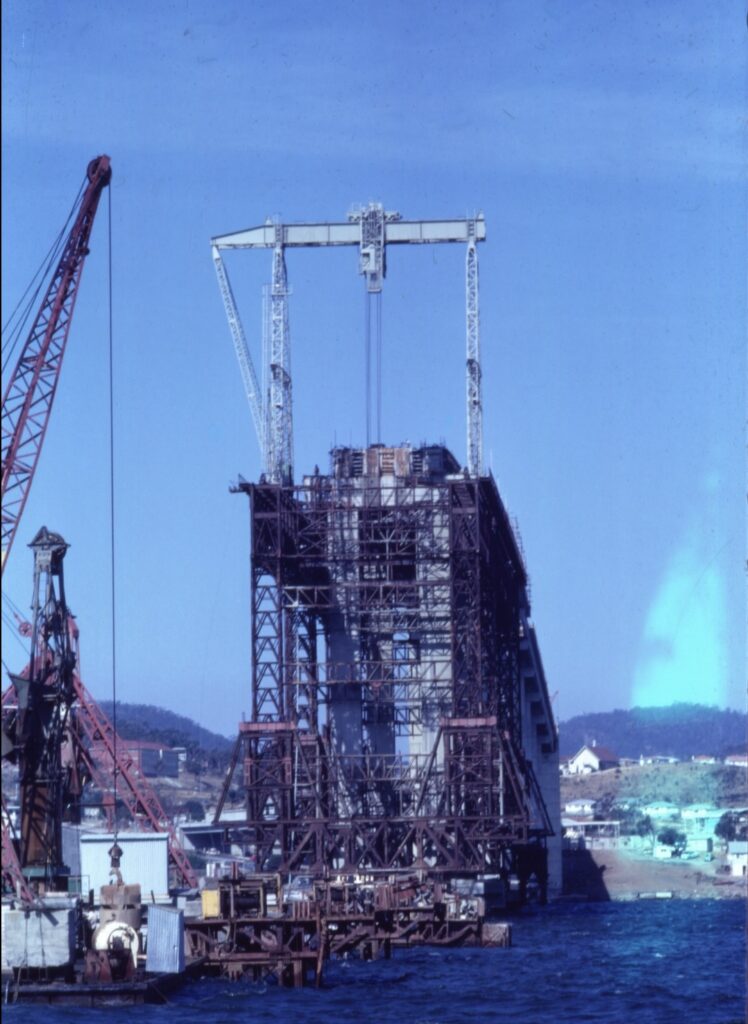

In April 1960, construction of the Tasman Bridge commenced, undertaken by a British firm. Notably, the final design included a high number of pylons, which would later prove to be a challenge for ship navigation.

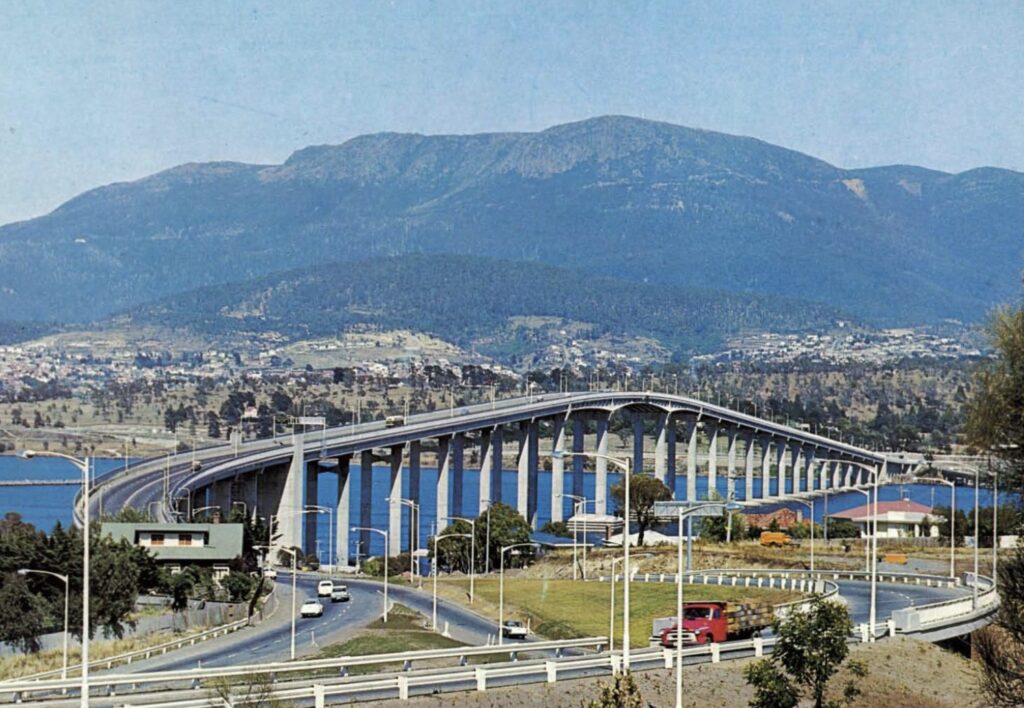

Two lanes of the bridge opened on 18 August 1964, with the full four lanes available by 23 December of the same year. The project’s total cost reached $15 million, more than double the original estimate.

Spanning 1.4 kilometres and 17.7 metres wide, the bridge was constructed using pre-stressed concrete, with major sections precast offsite. The structure used 61,000 cubic metres of concrete, 5,200 tonnes of reinforcing steel and 117 kilometres of pre-stressed cables. The bridge’s capacity was estimated at 4,000 vehicles per hour during peak times.

Officially opened on 29 March 1965, by the Duke of Gloucester, the bridge quickly became a symbol of Hobart. However, locals noted that the abstract sculpture unveiled during the ceremony, intended to represent the “soaring arc” of the bridge, better symbolised the soaring costs.

The Tasman Bridge served as Hobart’s vital artery, linking the eastern shore’s growing suburban population with the city. At the time of the accident, around 30 per cent of Hobart’s residents lived on the eastern shore and relied on the bridge for daily commutes.

The old floating bridge’s two towers remained in place for several years before being eventually dismantled.

The ill-fated voyage of Lake Illawarra

For its voyage to Hobart in January 1975, The Lake Illawarra was en-route from South Australia, carrying 10,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate bound for Hobart’s Electrolytic Zinc Company’s treatment plant at Risdon.

Masters of some ships were allowed to navigate the passage under the bridge provided they had passed an exam to gain exemption, and they had made three voyages under the bridge – one in darkness while under supervision. Captain Boleshaw Pelc, an experienced seaman, had navigated this passage many times before.

However, on the fateful night, a strong tidal current and inattention caused the ship to drift off course. Instead of heading for the central navigation span, the ship veered towards one of the smaller, eastern spans.

The crash

On Sunday 5 January 1975, thousands of Hobart residents crossed the bridge, enjoying the summer vacation. The bridge was a vital link to popular destinations like the Tasman Peninsular, the East Coast and Hobart’s beaches.

As the steam turbine ship Lake Illawarra approached the bridge that evening, it was travelling at eight knots. Most of the 42 crew members were off duty, relaxing in the amenity rooms. A light south-westerly wind blew at three to four knots, and low tide occurred at 9:12 pm.

Around 9:25 pm, as the ship neared the towering concrete pylons of the bridge, Captain Pelc realised something was wrong. The shore leading lights he relied on to guide his approach were shifting in an unusual way. He quickly ordered a course correction northward and ordered engines to “slow ahead” to reduce speed. Although the ship was capable of passing through the central navigation span, Pelc mistakenly aimed for one of the narrower eastern spans.

The bow began to swing starboard. Despite Pelc’s insistence that the leading lights were incorrect, his repeated course adjustments proved ineffective. A vessel that size couldn’t quickly respond due to insufficient steerage, and the bow continued to drift towards the eastern shore and the bridge.

Pelc frantically ordered engines to stop and desperately commanded “hard a port” to shift the rudder. Despite confirmation from the helmsman, the ship failed to respond. By this time, the Lake Illawarra was less than 300 metres from the bridge, and Pelc knew the collision inevitable. His last resort was to reverse the engines at full speed, but by then, control was lost. The bow continued its swing to starboard, and in a final, desperate measure, Pelc ordered both anchors dropped, with only the port anchor released as the bridge loomed overhead.

The Lake Illawarra drifted helplessly between the central navigation span and the eastern shore, and the bow almost gently struck the capping of piers 18 and 19. The impact was catastrophic. A 127 metre section of the bridge’s roadway, supported by three spans, collapsed into the river – 7,000 tons of reinforced concrete crashed onto the ship’s foredeck.

Crushed under the weight of the concrete, the Lake Illawarra sank in about 10 minutes, settling more than 35 metres beneath water. The ship’s bow submerged first, while the stern pointed skyward, before sinking in a cloud of spray. Six crew members were trapped and drowned; another was killed while on deck trying to release the second anchor.

The remaining crew attempted to scramble to the stern. Twenty made it to the ship’s boat, the rest jumped or dropped into the cold, fast-flowing river and were rescued.

Many residents along the shore watched in disbelief as the Lake Illawarra passed unusually close before striking the bridge. Small boats quickly arrived at the scene to rescue survivors, and the Water Police launched within 20 minutes to assist in the effort.

The traffic

Although traffic was relatively light that evening, the collapse of the bridge took several drivers by surprise. Without warning, four cars plunged into the gap created by the falling roadway, disappearing into the Derwent River below – three vehicles were travelling from the western side, and one from the eastern side.

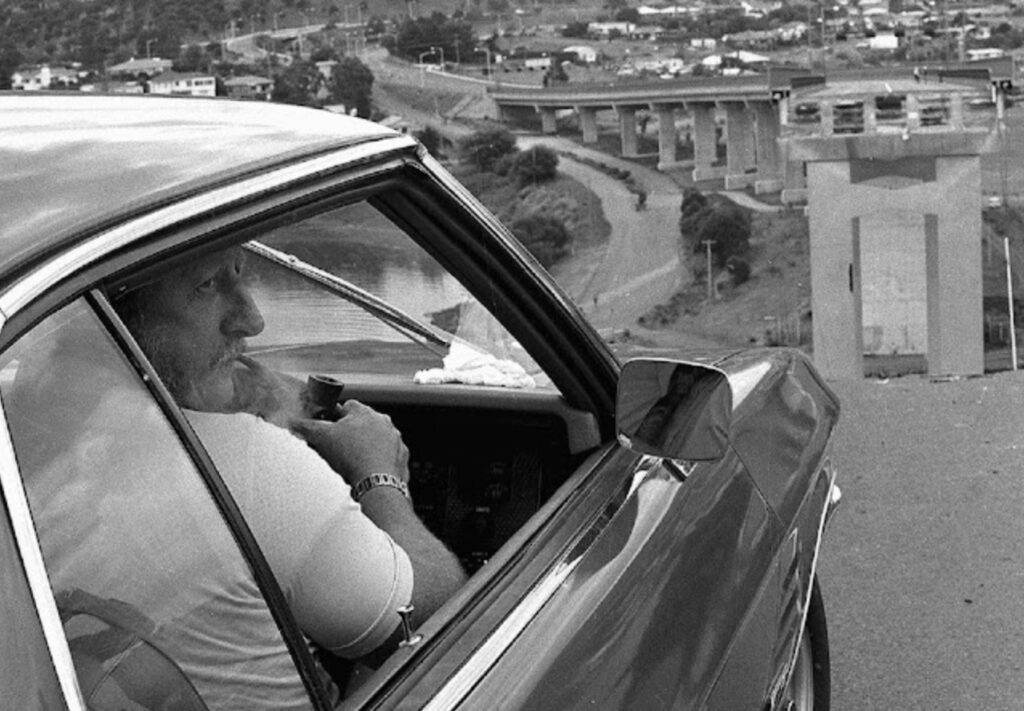

Other cars teetered dangerously on the edge, their occupants on the brink of death. One was a silvery-green 1974 Holden HQ Monaro GTS coupe carrying Frank Manley, his wife Sylvia, their 16 year old daughter Sharon, and her boyfriend. The family were on their way home to Cambridge after a barbeque in Geeveston. As they crossed the bridge, they initially thought a power failure had caused the lights to go out. Manley then spotted what appeared to be a broken-down car ahead. But his wife quickly realised something far more serious was wrong – the white lane markings had vanished. She screamed for Frank to stop, prompting him slam on the brakes just in time. The front wheels of the Monaro went over the edge, and the car hung precariously, with only the back wheels and the underside of the transmission keeping it from lunging into the river.

Remarkably, the Manley family managed to escape the car and reach safety.

Murray Ling, travelling in the same direction with his family of four, was not far behind the Manley’s. After witnessing two cars disappear into the void, he realised the danger ahead and slammed on his brakes, bringing his Holden EK station wagon to a halt, inches from the edge. His entire family exited the vehicle and began desperately waving at other drivers to stop. Unfortunately, one failed to stop in time, crashing into the rear of the Ling’s car and pushing it over the edge, where it came to rest beside the Monaro.

Horrified, the Lings and the Manleys could only watch as two more cars plunged into the river, despite their efforts to warn them.

Of the vehicles that plunged into the river during the disaster, one was recovered on 7 January 1975. Another found buried under rubble the next day, and a third was discovered on 10 January. The fourth vehicle was never found.

The immediate aftermath

In the immediate aftermath, rescue efforts were launched to look for survivors. Navy divers were flown in to search the murky depths of the Derwent, contending with strong currents and treacherous debris. It was dark and it was almost impossible to see anything. The only lights were from the two car’s headlights as they hung precariously over the edge of the bridge.

Crewman Max McDonald had sunk below the surface of the water when rescuers Jack Reed and his son Kevin grabbed him by the ear and yanked him to safety. They were one of the first rescuers, like angels in the night who performed a miracle.

Although several bodies were recovered, the remains of Dr Thomas Jones, one of the motorists, were never found. His disappearance remained a mystery for over 40 years until a coroner officially declared him dead.

The Hobart Mercury summed up the situation the following morning:

There was an air of unreality about the disaster.

The bridge’s collapse threw Hobart into chaos. Almost immediately, the eastern suburbs were isolated, and the loss of the bridge severed vital connections for thousands of residents, about 30 per cent of Hobart’s population.

They could still get to the western shore, but the few minutes’ drive across the bridge was replaced by the need to queue for passenger ferries for perhaps an hour or more at peak times or drive many kilometres upstream by a circuitous route to an older crossing at Bridgewater which added another one and a half hours to get into the city.

Following the collapse of the original bridge, a large-scale salvage operation was carried out to clear the navigational channel. Nearly 25,000 tons of concrete were removed and towed back to Geilston Bay, the original site of the bridge, just upstream from the new structure.

The ferries and temporary Bailey Bridge

Ferries were hastily mobilised to reconnect the eastern shore with the city. By the day after the tragedy, three private ferries and a government cable punt were already operating from an anchorage below the Tasman Bridge. Two weeks later, another private ferry service began from a bay just above the bridge, and by the end of the month, yet another joined the effort. In February 1975, a larger government ferry arrived from Sydney, followed by a similar vessel at the end of May.

However, despite these efforts, the temporary ferry system was expensive, inefficient and far from ideal, but it was the best the government could implement under the circumstances. Long queues, delays, and overcrowding became a daily reality for many.

The ferry service faced continuous problems. The government and public service struggled to cope with the new reality, often making decisions on the fly. As issues mounted, the need for quick, agile responses became apparent – something the public service wasn’t equipped to handle effectively.

By early March 1975, improvements were made. Terminals were upgraded, shelters were erected, and an information booth was opened. A proper ferry timetable was introduced the following month, offering 15-minute service intervals during peak hours, which stretched to hourly services at off-peak times. An all-night service ran from the downstream eastern terminal.

In the weeks following the collapse, the government considered constructing a temporary bridge north of the damaged Tasman Bridge to restore a road access. However, the idea was quickly abandoned when studies revealed the risks associated with building a lengthy pontoon crossing.

Instead, the Army and government agreed on a Bailey Bridge, with funding provided by the federal government. Construction work began at Dowsings Point on the western side and Cleburne Point on the eastern shore.

By 16 December 1975 a single lane Bailey Bridge was completed further upstream, at the site of what is now Bowen Bridge. The new bridge became immediately popular, facilitating over 8,000 trips every day.

Despite its success, congestion was a frequent issue. Complaints arose when commercial vehicles were given priority access. Drivers had to queue in floodlit holding yards, which operated 24 hours, supervised by police. Traffic flow was controlled by lights, and the bridge was closed whenever winds exceeded 80 knots.

These measures remained in place, serving Hobart until the Tasman Bridge was fully rebuilt and reopened nearly two years later.

A replacement bridge

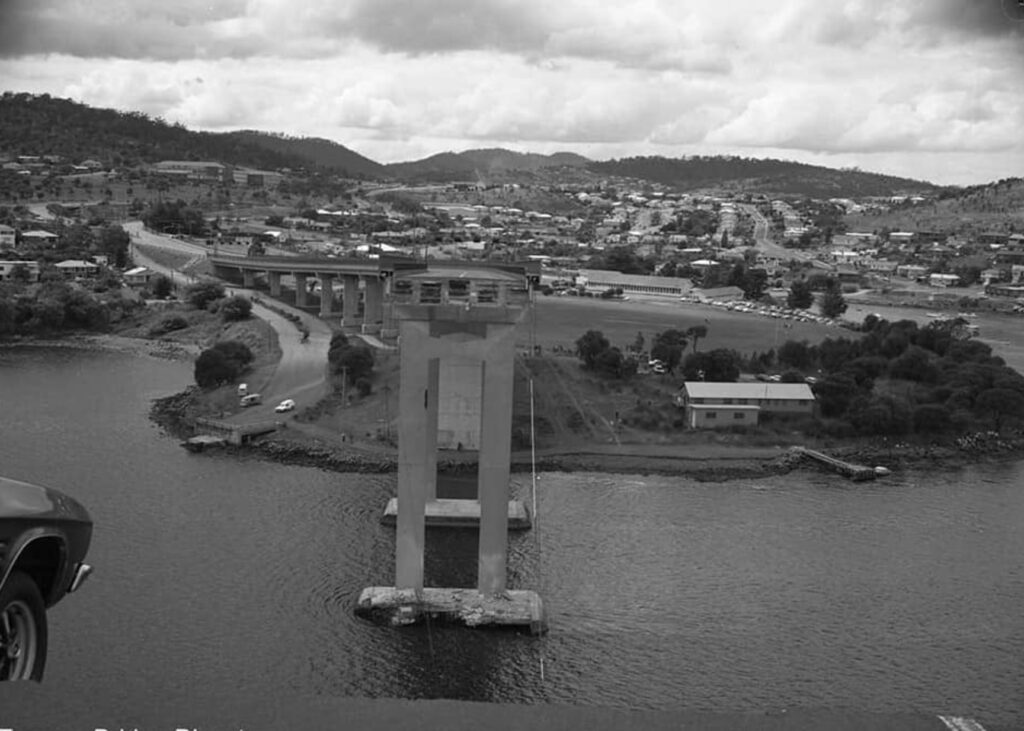

Three days after the partial collapse of the Tasman Bridge, authorities discovered a troubling situation: part of the eastern side of the bridge was precariously supported by just eight stainless steel bolts. While immediate surveys indicated the span was stable – for the time being – this temporary solution highlighted the urgency of reconstruction.

Engineers quickly determined that rebuilding the bridge to its original design was impossible, largely due to the wreck of the Lake Illawarra. The bow of the sunken ship now covered the site where pylon 19 once stood, and the remains of pylon 18 were blocked by the collapsed sections of the bridge. Large portions of the wrecked deck also obstructed access to critical areas.

As a result, a new design was developed eliminating pylon 18 and incorporating a stronger pylon 19. The revised plan also allowed for a slightly wider structure, increasing the bridge’s capacity from four lanes to five.

The engineers faced significant challenges but overcame them with innovative solutions. They constructed underwater walkways, railings, and even a monorail system to transport struts into place. A complex lattice network was installed to support new pylons – a complete underwater scaffolding project that pushed the limits of what was possible at the time.

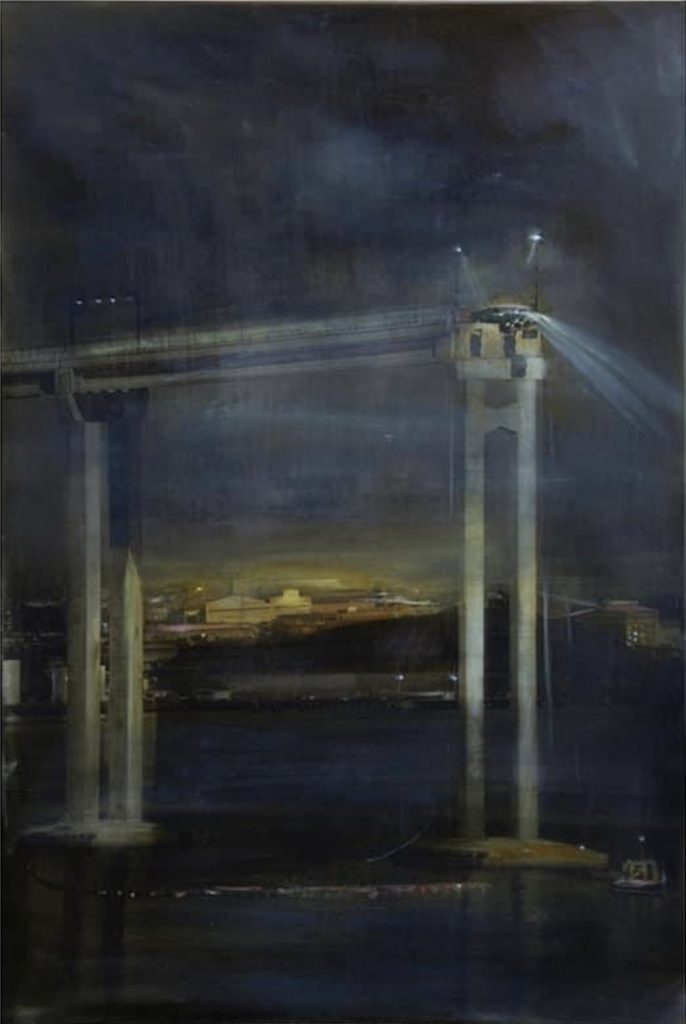

Reconstruction officially began in October 1975 and took two years to complete, with a total cost of approximately $44 million funded entirely by the federal government. On 8 October 1977, the newly built Tasman Bridge was officially reopened, marking the end of a challenging chapter in Hobart’s history.

The marine inquiry

A court of marine inquiry, presided by two judges, delivered their findings on 30 April 1975. The inquiry concluded that Captain Pelc had strayed off course due to a combination of tidal currents and inattention. Additionally, it was found that Pelc had approached the bridge too quickly before attempting to align with the lead lights. His error was further compounded when he stopped the ship’s engines, causing it to lose steerage.

Pelc was found guilty of misconduct for careless navigation and had his Certificate of Competence suspended for six months. While the court ruled he had not handled the ship in a proper and seamanlike manner, his actions were not deemed to be criminally negligent or incompetent.

In response to the findings, a pilot system was introduced for all ships passing under the Tasman Bridge to prevent future accidents.

The inquiry also recognised the bravery of 28 year old shipwright, Able Seaman Graham Kemp, who was tragically killed while following orders to drop both anchors, even as the broken bridge loomed dangerously overhead.

According to the ship’s chief engineer, Noel Dalton, Captain Pelc had also failed to inform the crew in the engine room that the ship was sinking. Dalton, who was off duty at the time, took it upon himself to warn the crew below, likely saving their lives. Without his actions, the outcome for those in the engine room could have been far worse.

The wreck of Lake Illawarra

Though the Lake Illawarra had sunk beneath the Derwent in 1975, the wreck remained largely undisturbed for decades. It wasn’t until recent technological advances in marine exploration that the full extent of the wreck was rediscovered and mapped in stunning detail.

In 2022, a team from the CSIRO and the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) used advanced sonar technology to map the remains of the Lake Illawarra. The sonar, mounted on the research vessel Morana, revealed a detailed image of the ship resting on the riverbed. The mapping process took approximately one hour, providing researchers with new insights into the state of the wreck and its impact on the river’s ecosystem.

The rediscovery of the wreck serves as a poignant reminder of the tragedy that shook Hobart nearly five decades ago – a disaster that forever altered the city.

Manley’s Monaro

Frank Manley’s Holden HQ Monaro become infamous for dangling precariously over the edge of the Tasman Bridge on the night of the disaster. Remarkably, the car is still in its original condition and is now on display at the Launceston Motoring Museum.

Frank purchased the Monaro brand new just a few months before the accident, and the family still owns it today. As the car became a part of Australian history, they couldn’t bring themselves to part with it.

Frank, a former racing driver, had competed at the renowned Longford Circuit in the early 1960s in an FE Holden. He also raced at Baskerville, winning the Touring Car Handicap at a race meeting in December 1965.

There are few genuine one-owner HQ Monaros left, especially with fewer than 100,000 miles on the clock, making this car a rare and iconic piece of Australian motoring history.

Adding new layers to an important and uniquely Tasmanian tale; with even more areas to explore further.

Robert, another great blog as always. John

Murray in wrong car smokin a pipe.