After the Snowy, she was a nation.

Nelson Lemmon

Thank God we had visionary leaders and the world’s best engineers in Australia 75 years ago. Without their efforts, the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric scheme – one of the seven engineering wonders of the world – might never have come to fruition.

This monumental project blended innovative thinking, engineering brilliance, and the dedication of a diverse workforce. It stands today as a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance.

Vision and Genesis

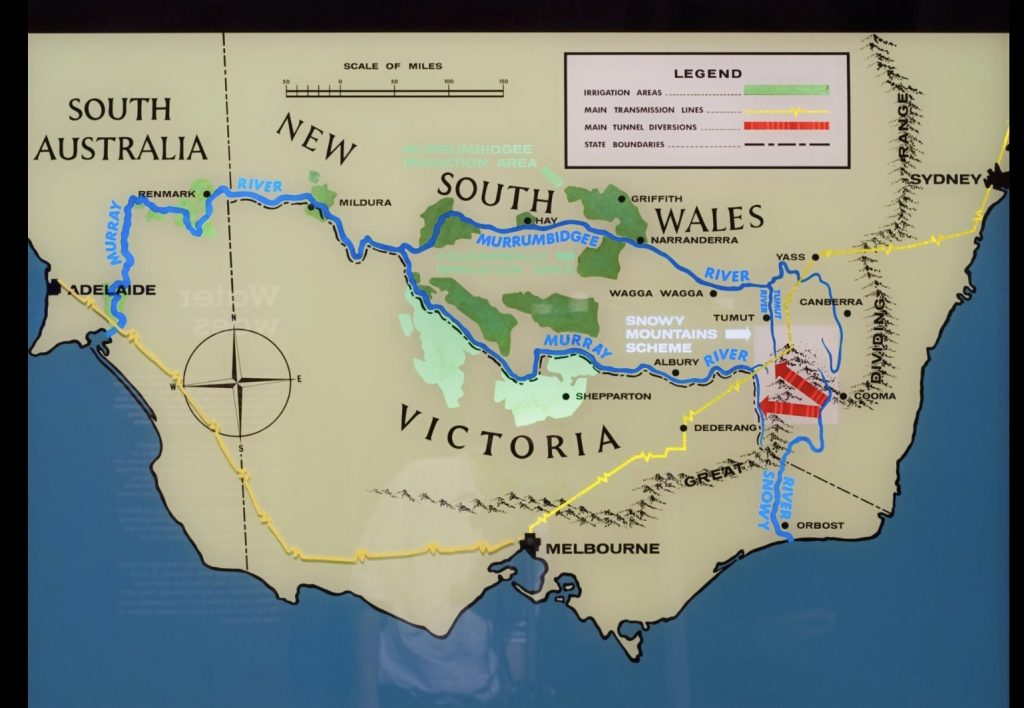

Harnessing the Snowy River’s waters was first proposed in the 1880s to irrigate the dry plains of southern New South Wales and northern Victoria. Initially, the Scheme was simple in thought – to satisfy the urge to populate the dry inland. Over decades, however, the idea evolved to include hydro-electric power generation.

The unique terrain of the Snowy Mountains is ideal for generating hydro-electricity. The alpine peaks are very effective at harnessing and enhancing precipitation. Capturing, storing and diverting the water from snow melt combined with rainfall using aquaducts and trans-mountain tunnels was the idea behind the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

It was not until 1944 that Commonwealth and State governments formed a committee to seriously examine the development of water resources in the Snowy Mountains area. At its heart, the Scheme’s early ambitions sought to solve two pressing challenges – power generation and water scarcity. Post-war Australia needed abundant electricity to fuel industrial growth and reliable water supplies to transform the arid plains into fertile farmland. These dual needs shaped the Scheme’s design and galvanised national support.

Trygyve Olsen, the Norwegian engineer from the Victorian Electricity Commission, suggested a radical new approach. He proposed a tunnel under the Dividing Range to generate electricity. This dual-purpose vision soon gained traction. This innovation was aided and driven by the ambitions of Federal Government minister Nelson Lemmon and brilliant engineer William Hudson.

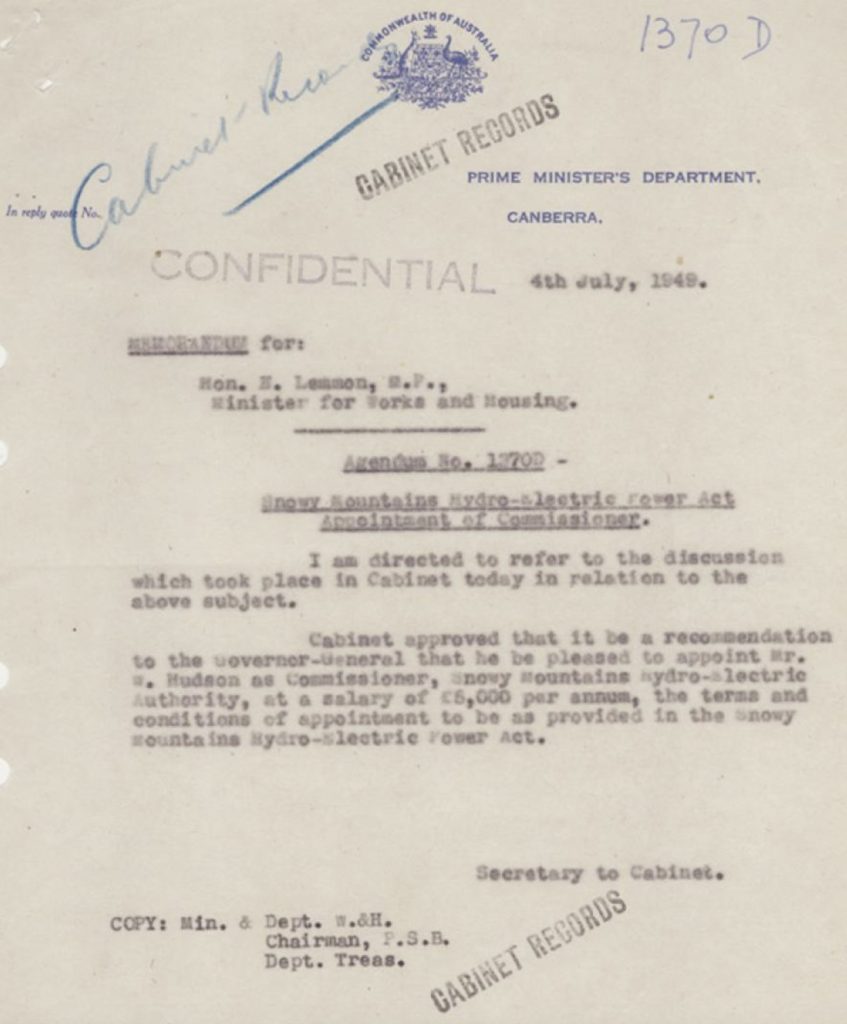

Lemmon, from the Wheatbelt in Western Australia, was instrumental in overcoming political rivalries and constitutional challenges. His ability to align the states’ interests with national priorities led to the enactment of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Power Act in 1949. It ended more than 60 years of plans and talks to develop the water resources emanating from Australia’s highest source. It was also the last policy undertaking of the Chifley government.

Recognising the transformative potential of Olsen’s plan, Lemmon approached it with cautious optimism. He organised detailed investigations, including precise aerial surveys using planes from the Air Force. Lemmon guided its rapid development once the proposal proved practical and feasible.

At the time, Australia was recovering from the war and the real threat the Japanese posed to the nation’s security. The government was determined to make Australia a powerful and modern nation that would be able to stand up for itself, especially against any future threat from the Asian region. A scheme promising increased power for industry and more water for agriculture held great appeal.

Lemmon’s greatest achievement was to set up the project under Commonwealth control to avoid the bickering of the states. To achieve his aim, he had to get the support of his Labor colleague, Herbert “Doc” Evatt, acclaimed constitutional lawyer and Attorney-General, to acquire land that was usually a state function and thus beat a constitutional roadblock by making the project a defence issue, but also convince Prime Minister Ben Chifley that the Commonwealth wholly fund the project.

The new Act was clear in its purpose – to set up the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority with adequate power to construct Australia’s largest public works ever contemplated.

While Lemmon was keen to get an Australian to lead the project, particularly as he believed the skill set was here after already building large dams and many tunnels at coal mines, he selected a Kiwi. To be fair though, William Hudson had left New Zealand in 1927 to develop his skills and experience working worldwide on several hydro-electric projects in France, New Zealand, Scotland and Australia.

To give the position an air of authority, Lemmon convinced his colleagues that the salary for the Commissioner of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority should be higher than the prime minister’s. It created the aura that set it apart from any other government job.

Together, both men laid the foundation for an unprecedented undertaking.

The development of the Scheme

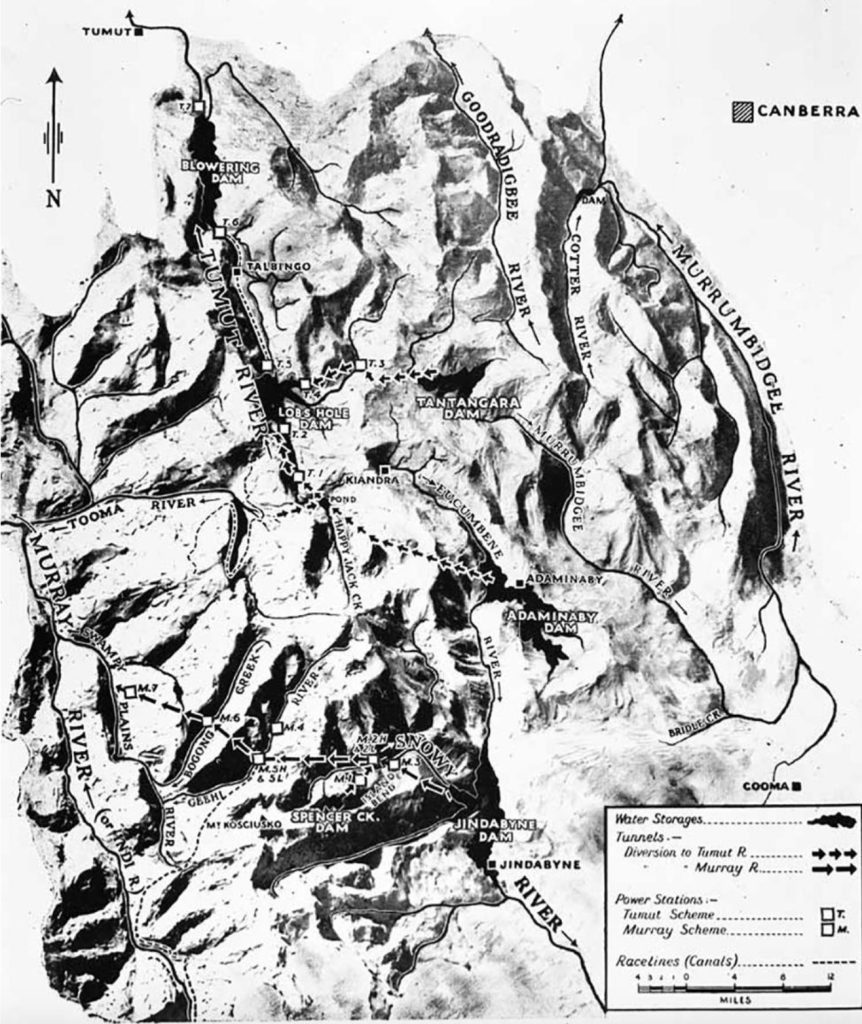

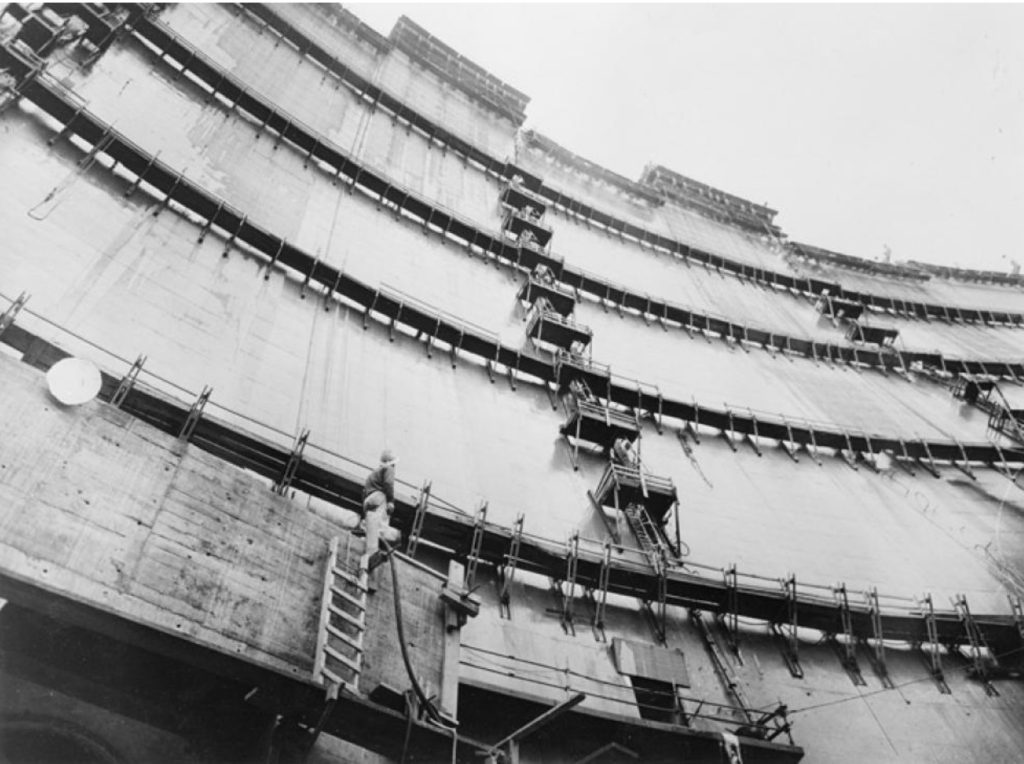

The Scheme’s scale and complexity were unparalleled. Over 145 kilometres of tunnels were bored through the rugged mountain terrain, linking 16 power stations – two were underground—with seven major dams and nine smaller ones. It captured the waters of 12 rivers and 71 creeks, rerouting them westward under the Great Dividing Range to irrigate the Murrumbidgee and Murray River valleys.

The Authority split the initial plan for Lemmon’s ambitious proposal into two distinct sections. One was the Snowy-Tumut development in the north of the mountains, which involved the diversion of the Eucumbene River, the upper Murrumbidgee River and the Tooma River to a tributary of the Murrumbidgee – the Tumut River. The other was the Snowy-Murray development to the south, which involved the diversion of the Snowy River to a tributary of the Murray River, the Swampy Plain River.

These reservoirs stored water, which was then channelled through tunnels and pipelines, descending from high altitudes to spin turbines in power stations. They generated 51 gigawatt-hours of electricity annually, fuelling industrial growth in New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, securing Australia’s energy future.

The flow of water, regulated by the Jindabyne and Adaminaby dams, was also channelled westwards via tunnels to be released into the Murray and Murrumbidgee valleys for irrigation. Subsequent investigations identified the need to link the two sections via a much bigger water storage system, and the original Adaminaby Dam became the Eucumbene Dam.

Technicians and specialists were sent all over the mountains to gather information and get to that level of planning. They had to know the geology, not just below the surface but many hundreds of metres lower. The heights of mountains and valleys had to be confirmed. It was also essential to measure the flow of rivers through the mountains, including the speed and volume.

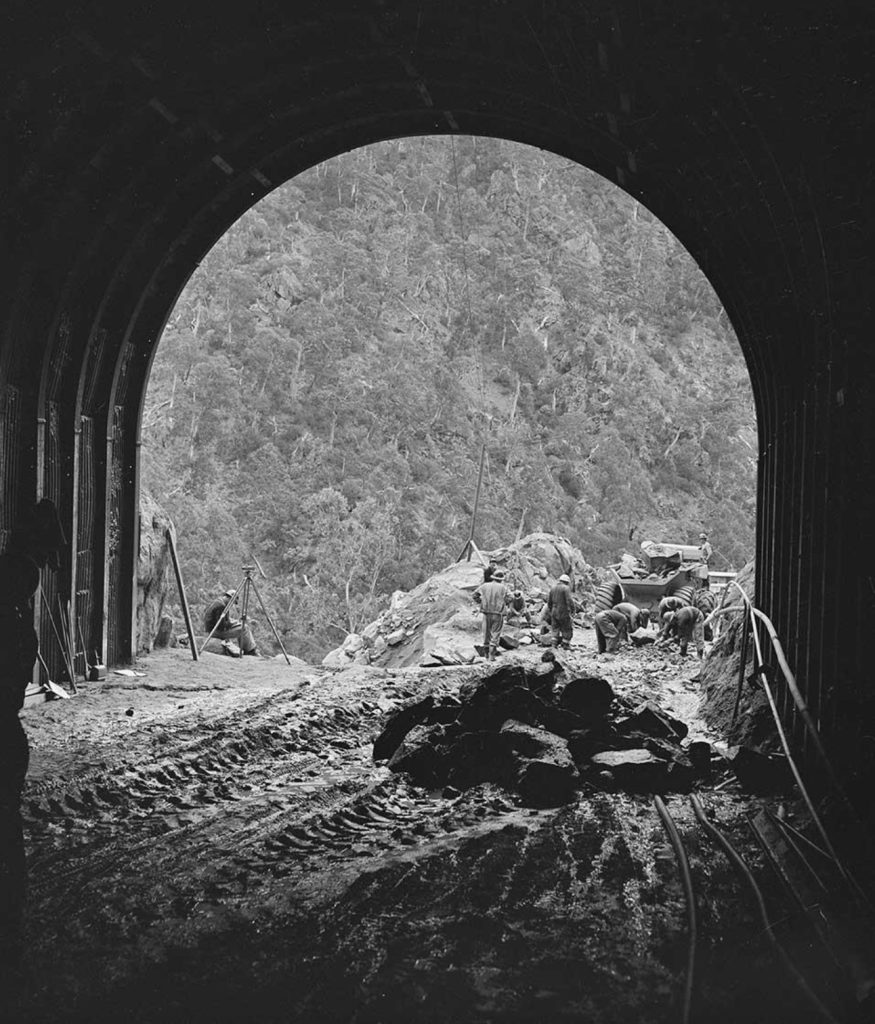

Construction begins

In the decade following WWII, a network of tributaries, both geographical and human, converged on the Snowy Mountains. The rivers had been there since time immemorial. Now invigorating currents of humanity came from afar, bringing new skills, vitality, ideas and ambitions.

The Scheme’s construction officially commenced on 18 October 1949, when the Governor-General Sir William McKell, in brilliant sunshine in a lonely gorge high above the Monaro Plains, detonated the first explosives at a lavish ceremony below the Eucumbene River gorge. It marked the start of a 25-year endeavour.

The original proposal had the waters rise to just below the township of Adaminaby, resulting in a lakeside town. However, after further investigations and engineering work, the Snowy Mountain Authority chose a second site for the dam wall, six kilometres downstream, to allow for greater water storage and increase the efficiency of the project.

It meant that a significant portion of the town would be flooded and had to be relocated. It was a challenging task for the Authority, who were treated with disdain and suspicion by the 600 locals. In addition, much of the land to be flooded was prime grazing land, and the Authority had to offer generous compensation for displaced residents and farmers.

According to Hudson:

From a national viewpoint…the loss of this historic township and the pastures of the Adaminaby Basin is more than justified by the enormous potential of the water.

Relocations began in 1956, with 102 buildings and two stone churches moved. Four buildings that were above the high-water mark stayed where they remain today. Unfortunately, many historic Victorian-era buildings and artefacts were lost, and no effort was made to record the old town before its destruction. Only 250 people moved to the new location nine kilometres away over the Great Dividing Range.

In a sad irony, the ceremonial plaque unveiled by the Governor-General during the oroginal plans, now rests 90 metres underwater.

The first major undertaking of the Scheme was the Guthega section, including the Eucumbene Dam, tunnels, and a power station. The Authority advertised tenders worldwide, particularly as they worried that its engineers didn’t have the experience and design skills to break new ground. Additionally, there were very few organisations in the world equipped to deal with the scale and size of the work involved. The leader in the field then was the United States Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), whose huge hydro projects included the Hoover Dam and the Tennessee Valley Irrigation Project.

Early in 1951, the American government made the USBR’s chief construction engineer, Wilbur Dexheimer, available for six weeks. It was the start of a ten-year association that greatly benefited the Australian engineers and the Snowy Scheme.

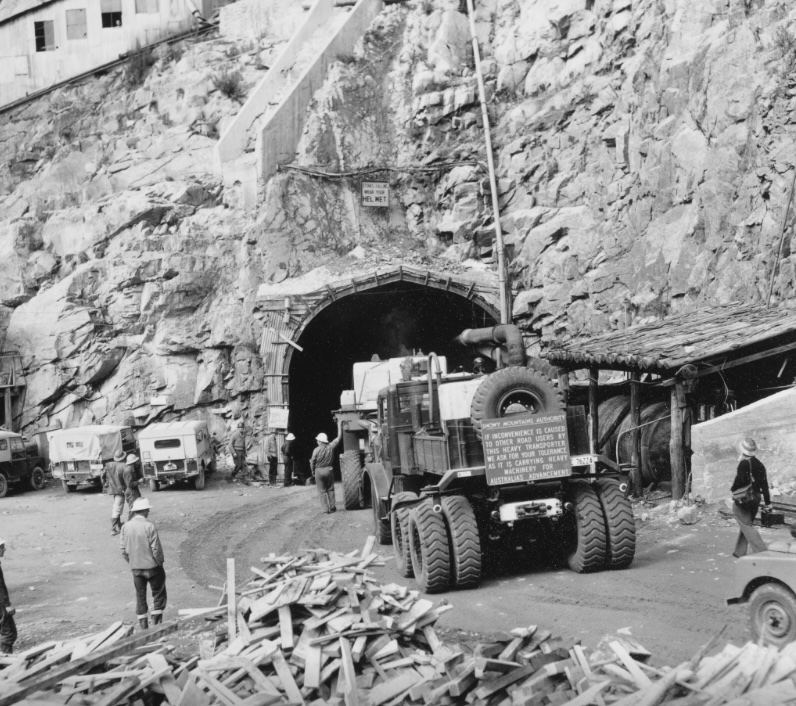

By this time, the Authority had over 2,300 employees. They installed a radio network to link Cooma with the remote regional bass, strengthened main roads, built new ones past Island Bend towards Guthega, and a generator provided power for the Upper Snowy sites and camps.

The Guthega section required designing and constructing a dam 30 metres high and 107 metres long, a tunnel 4½ kilometres long, a pipeline and a power station building. Norwegian company Ingenior F Selmer won the tender. It was their biggest-ever engineering undertaking, bringing their workforce, many of whom were rural workers from the Arctic Circle.

The first fatality occurred during the building of the Guthega Dam. A Norwegian was crushed by a falling rock in March 1952, followed by another in January 1953. In total, seven men died during the three and half years of the Guthega project, and surprisingly, none were from bulldozer accidents. This was despite clearing the penstock, which involved incredible dozer works in country so steep:

The dozers looked like flies from the other side.

On 23 April 1955, the first formal opening of the Snowy Scheme took place when Prime Minister Robert Menzies launched the Guthega project.

In early 1954, The Authority sought tenders to build two major sections – the Eucumbene to Tumut tunnel and Happy Jacks Dam, the Tumut Ponds Dam and the Tumut 1 pressure tunnel. They awarded the works to the large American company Kaiser-Walsh-Perini-Raymond. It was a significant moment that changed the Snowy Scheme and altered civil engineering procedures across Australia.

The Americans ran a tight ship and very efficient operations, which contrasted with the more relaxed Australian attitude that when God made time, he made plenty of it. Their equipment was all new, well-maintained and geared for full-time production. They planned every little job to ensure no one sat idle and everyone had a task, much like a production line in a factory. The Snowy Scheme taught Australians, in the words of Robert Menzies:

To think in a big way, to be thankful for big things, to be proud of big enterprises.

The Kaiser group began constructing the concrete arch dam at Tumut Ponds in November 1955 and completed it five months ahead of schedule. In June 1956, they took over the construction of the Adaminaby Dam, one of the largest earth-rock-fill dams in the world at the time and the biggest ever built in Australia. They were given four years to complete the work and achieved it in under half that. This was after the original contractors were two years behind schedule after six years.

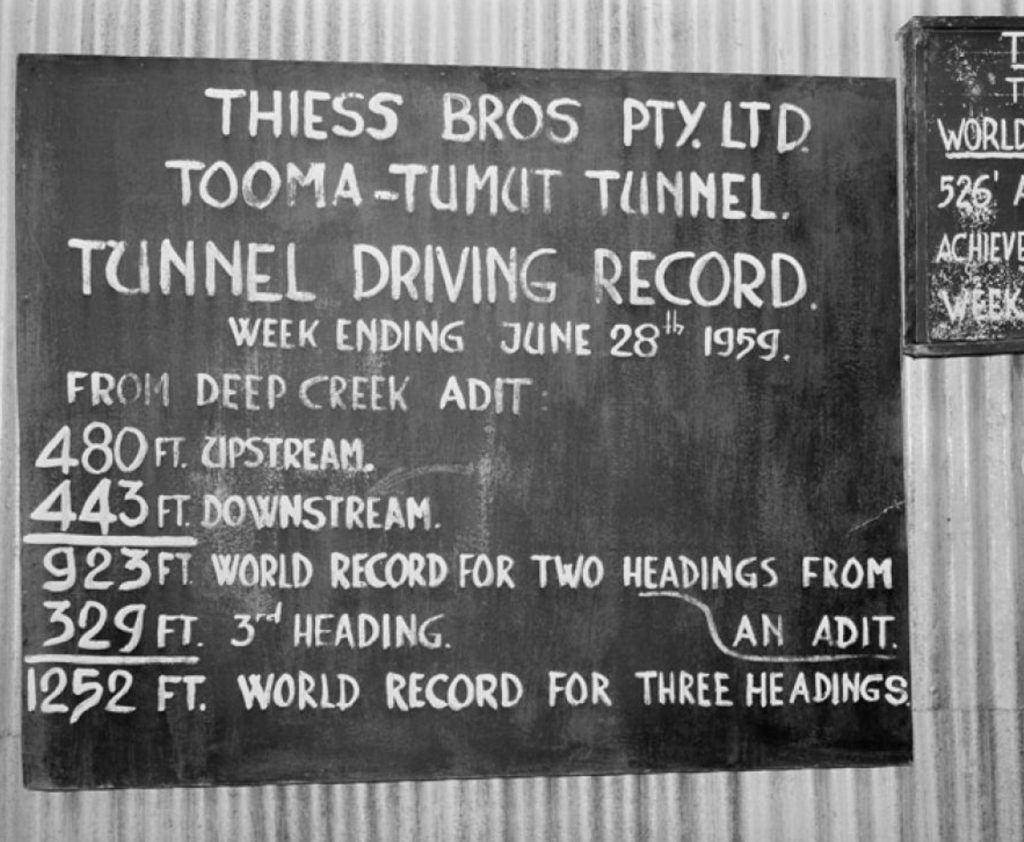

In 1958, Thiess Bros became the first Australian company to win a major project on the Snowy, and they went on to build a quarter of the whole Scheme. The Authority was still relying on USBR to design the major works, but by the mid-1950s, an Australian engineer, who rose to head of civil design, took over design work, which started with Tooma Dam and Thiess’ first project. Other Australian companies, such as Humes, John Holland and the Australian General Electric Company, followed suit.

By 1959, the Kaiser construction phase supplied electricity for New South Wales, marking a significant milestone and allowing the development of new industries that required abundant power.

The 1960s brought significant advancements, including constructing the Jindabyne Dam, Tumut power stations, and Murray 1. Engineers employed cutting-edge tunnelling techniques and built larger-scale dams, showcasing Australia’s growing engineering prowess. These years also saw innovations in hydro-electric technology, such as high-capacity turbines, remote monitoring systems and 330kV transmission lines.

Perhaps the most significant engineering accomplishment was the pioneering technique of pattern rock bolting to replace concrete lining as a cheaper and safer means of supporting patches of “dicey” rock in tunnels.

Well before the project was completed, it was nominated by the American Society of Civil Engineers as one of the world’s engineering wonders in 1962.

Jindabyne was another town in the Snowy Mountains that was transferred to its present location in the 1960s. It was due to the construction of Lake Jindabyne. Jindabyne was initially situated on the banks of the Snowy River, where the main river crossing was for cattle travelling between the Monaro and Gippsland. After a bridge was built in 1893, the town thrived.

In preparation for the move, plans began in 1959 to shift the 250 residents, but the Authority only relocated a few houses. Most residents took up the option of a council loan and had replacement houses built. Residents held a symbolic farewell to the old town in December 1964, where they crossed the bridge for the last time and walked up the hill to their new homes. In 1967, an army demolition team blew up the bridge, signifying the end of a link to pioneering heritage.

The final phase of the Snowy Scheme completed the intricate network with the Tumut 3 pumping and power station and the Blowering Dam complex. These additions ensured optimal water storage and power generation, bringing the vision to fruition. By the time the last components were operational in 1974, the Scheme had become a hallmark of global engineering excellence.

Another settlement with a far richer history was also affected by two dams. While Talbingo was just a station, a homestead and a pub, it hosted stockmen and drovers on their way to the snow leases without dismounting. They would ride in on their horses. Its most distinguished resident was Miles Franklin, born at the station. Because only five families were affected, the settlement was not shifted to a newer location.

Each dam, tunnel, and power station was an engineering marvel in its own right. For instance, the Tumut 3 power station introduced reversible turbines capable of pumping water back uphill during low-demand periods, maximising efficiency and ensuring a consistent electricity supply.

The Snowy Scheme’s real story

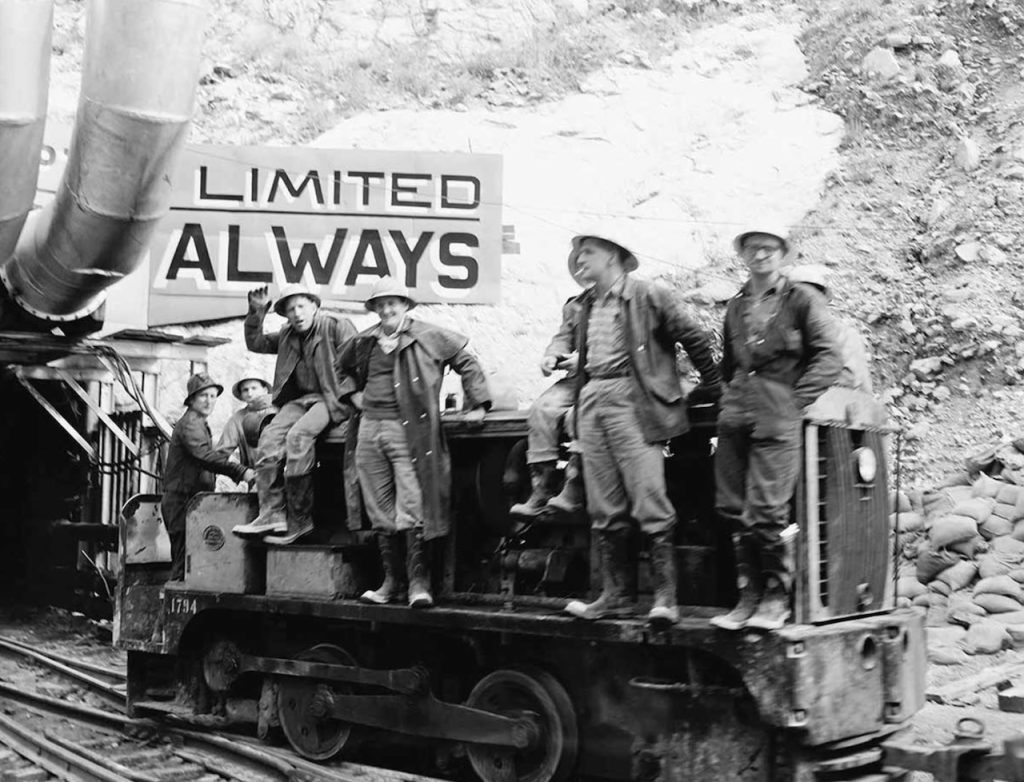

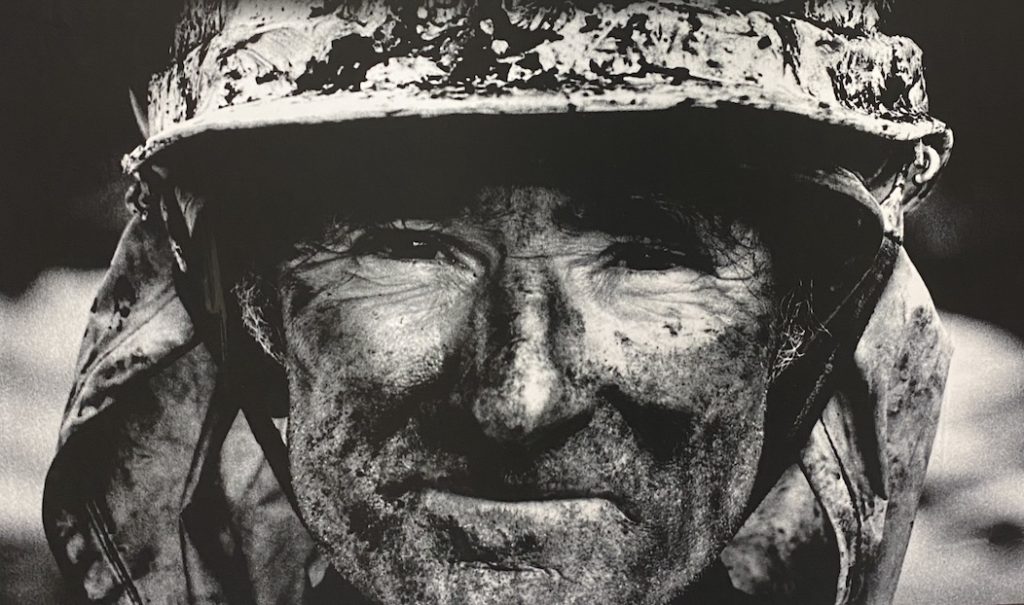

While the Snowy Scheme is an engineering tale about giant trucks, bulldozers, drilling, blasting, and welding in Australia’s most rugged and coldest region, it is also a story about people—all 170,000 from 71 nationalities—who brought it to life.

In the years following World War II, Australia lacked the workforce to undertake such a massive project. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority needed hundreds of experienced engineers, technicians, tradesmen, and thousands of labourers. The solution was to recruit labour from European countries ravaged by war. Millions of displaced persons lived in camps across Western Europe, and Australian officials travelled there to recruit workers.

The new arrivals were enticed by the promise of comfortable accommodation, but were shocked when they arrived. Single men lived in tents, and families were housed in simple wooden huts that kept out the snow but little else. For displaced refugees, however, these conditions were a vast improvement over the crowded camps they had left behind. It was a chance to work hard and build a new life to replace years of uncertainty with hope and purpose.

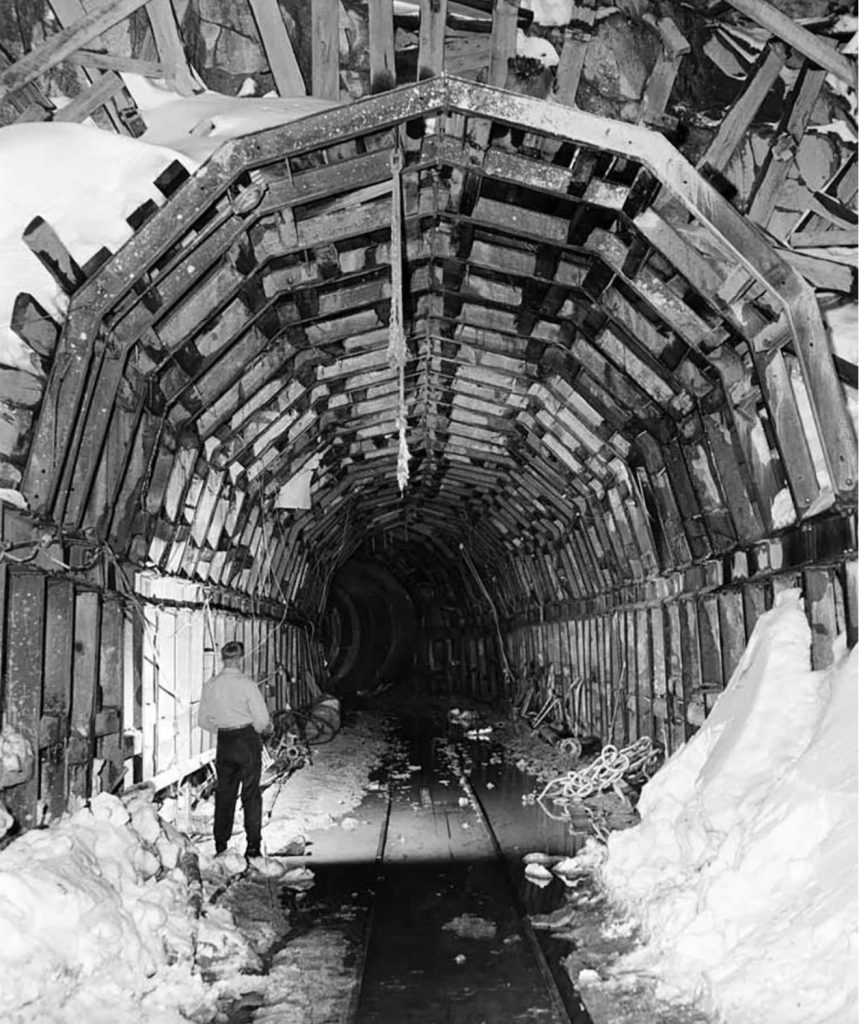

The workers had to live and work in unique locations across the Snowy Mountains. For several months of the year, these locations reached sub-zero temperatures all day and night. Tumut Pond camp had a reputation for being the coldest locality.

The workforce’s diversity was reflected in the roles they assumed. Italians dominated masonry work, including tunnelling and building retaining walls. Germans often filled skilled trades such as carpentry, mechanics and electrical work. Yugoslavs became miners and semi-skilled tradesmen, while Australians preferred operating machinery on the surface, driving the machines to build dams and roads.

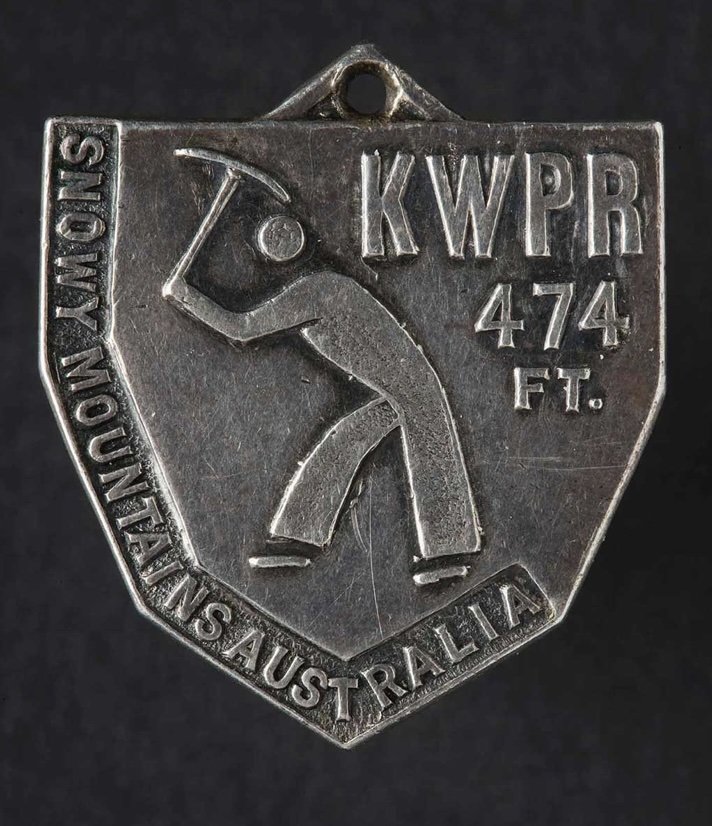

Under the driving force of Hudson, combined with a workforce keen to achieve something in their adopted country, the Snowy Scheme distinguished itself against other projects. Anyone afraid or incapable of hard work didn’t last long on the Snowy. To earn the highest wages, men agreed to work practices that are considered illegal today. For example, a tunnel worker was paid about three times the average Australian salary, with free food and accommodation. However, the amount earned depended on the speed at which the tunnel was constructed. The contractors paid miners a footage bonus – the further they advanced past an agreed minimum footage, the more they received. It all added to the risks.

The Eucumbene-Tumut tunnel, at 22.2 kilometres and the longest ever built in Australia, was completed in June 1959, four months ahead of schedule. The tunnellers set a world record of 148 metres excavated in one week. But the speed led to 15 fatalities.

The work was physically demanding and dangerous, especially in tunnelling. Men spent long shifts strapped to vertical walls, operating enormous jackhammers. Fumes and dust filled the tunnels, reducing visibility to almost nothing. Falling rocks could crush a man, live wires in the vicinity of watery surfaces and the constant fear of a premature explosion added to the dangers.

Tragically, 121 workers lost their lives, and thousands more were injured, with some losing limbs. The shared determination to succeed created a unique bond among the workers despite the risks.

For Australians, the Scheme also fostered a generation of skilled engineers who went on to lead significant projects nationwide. The Snowy’s legacy extended beyond its immediate achievements, inspiring innovation and expertise in infrastructure development for decades to come.

Transformative Impacts and Legacy

The Scheme’s impact was transformative. It turned the arid Riverina district into fertile farmland, enabling the growth of vast orchards and vineyards. Hydro-electric power drove industrial expansion, supporting Australia’s post-war modernisation. Beyond its economic benefits, the Scheme reshaped Australia’s cultural landscape, integrating a diverse immigrant workforce and enriching the nation’s multicultural identity.

For the Snowy Scheme and its many workers, the project not only put Australia on the world map but also created one of the greatest construction clubs anywhere in the world. For years after its completion, it was a badge of honour to be known as an “ex-Snowyite”.

Jindabyne became a focus for the ski industry, which grew directly from the Snowy Scheme. The area is now firmly established as a national park, and the rangers are doing their best to rid the legacy of the Snowy settlements where the residents planted lupins, daffodils and other non-native species. The Authority planted thousands of willows and poplars along roadsides to prevent soil erosion on the steep road batters, all under the blessing and careful eye of the Soil Conservation Service as part of strict erosion control measures.

While the Scheme had many benefits, it also had ecological consequences. Diverting large quantities of water from natural river systems altered local ecosystems and affected native species. The Snowy River, in particular, saw a significant reduction in flow, prompting calls for environmental remediation.

Before the Scheme, the Snowy River flowed fast and free as it roared its way through 407 kilometres of New South Wales and Victoria from the alpine country into the Bass Strait at Marlo. The river’s defining characteristic was always the snow. When it melted, it fed the Snowy, one of three rivers to benefit from this bountiful water harvest. The spring release gave the Snowy its fabled white water and spring floods that could last for months.

When the last of the rock and concrete dams of the Snowy Scheme was placed across the Snowy River near Jindabyne in 1967, the life of the river downstream changed dramatically.

Only 25 megalitres per day, just one per cent of its natural flow, flowed below the Jindabyne Dam. The health of the river began to deteriorate.

Following the Snowy River Inquiry, an agreement was reached in October 2000 by the New South Wales, Victorian and Commonwealth Governments to allow an environmental flow at 21 per cent of the pre-dam flow by 2012. This was possible due to water use efficiency savings in the inland irrigation areas.

By 2009, environmental flows had increased markedly, and the river responded positively. It was already deeper and cleaner in many places. These initiatives to restore water to the Snowy River have managed to balance the Scheme’s original goals with modern environmental awareness.

The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme was more than just an infrastructure project. In many ways, it shaped parts of our nation’s history by symbolising national unity and progress. It demonstrated the power of vision, collaboration, and determination. As Australia faces new challenges in the 21st century with government policies aimed at dividing the country, the lessons of the Snowy—from innovative engineering to fostering inclusion — remain profoundly relevant 75 years years later.

Fantastic read – we need to remember that much that we take for granted meant changes to the environment .

As an engineer, I was only ever vaguely aware of what happened on the Snowy Scheme. I was overseas for much of that time too.

‘Tis a pity that Aussies have never accepted that hard work is necessary to achieve anything worthwhile!

Therefore, thanks Rob for the very detailed story and for letting the public read it.