Nostalgic beginnings

Growing up in Australia in the 1970s, I spent countless hours playing backyard cricket during those balmy summer evenings. Despite my love for the game, I never excelled, oscillating between dreams of being a superb bowler or a top-order batsman, yet failing to master either. My lack of skills was evident as I was always the 11th-picked player on our school cricket team, batting last and rarely bowling. At least I wasn’t the 12th man!

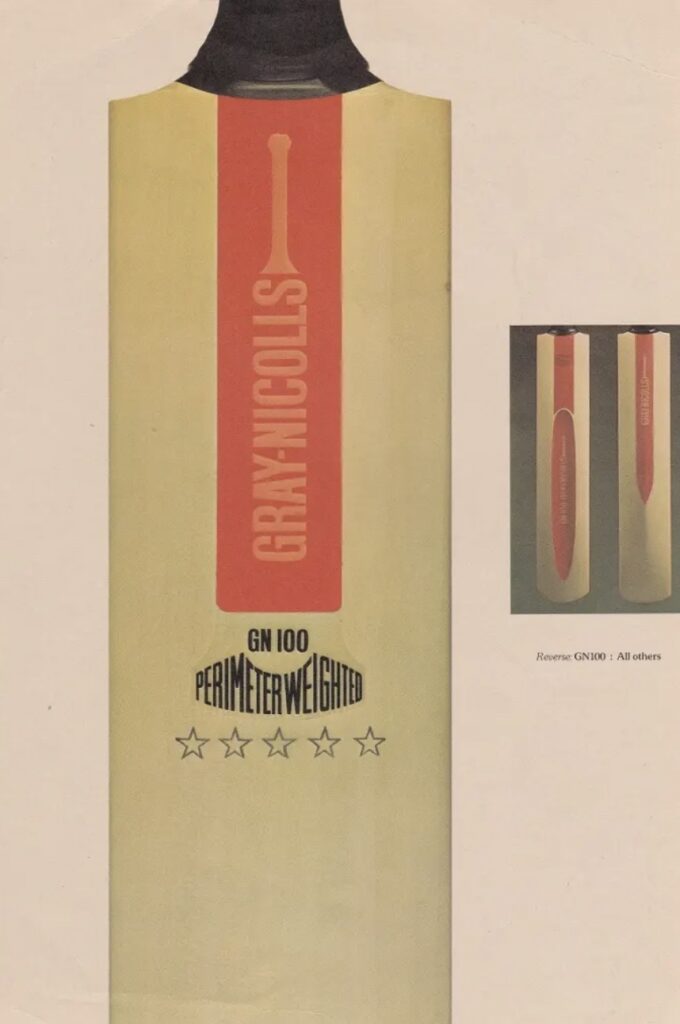

The cricket bat we all wanted for Christmas was a Gray-Nicolls, seen as the pinnacle of bat excellence. Unfortunately, I wasn’t good enough to own one of their bats.

Gray-Nicolls, the world’s longest-running cricket bat-making firm, has been producing bats for over 162 years from their factory in Robertsbridge, East Sussex. During the 1970s, every Test match opening pair wielded a Gray-Nicolls cricket bat.

The Scoop bat and innovative designs

These were the golden days for cricket bat manufacturing. This year marks a special anniversary of the Gray Nicolls Scoop bat. They turned bat making and marketing on its head by scooping out a section of the back of their bat. While it lasted about 20 years, a poll by Cricket Australia to mark its 50th birthday confirmed the Scoop as the most favoured cricket bat worldwide – well, at least in Australia.

The innovation focused on perimeter weight, a concept borrowed from golf. In 1972, South African golf club engineer Arthur Garner and British golf course designer Barrie Wheeler approached the Gray family, seeking to introduce this technology to cricket.

The aim was to increase the mass at the centre of the bat without adding extra weight, effectively spreading the weight across the back of the bat. This design was intended to enhance the sweet spot, making it larger compared to traditional cricket bats.

The Chappell brothers help pioneer the Scoop bat

Gray-Nicholls started making cricket bats in Australia in 1973 and needed a leg up to promote their bats. The Chappell brothers, Ian and Greg, were chosen as the pioneers to promote The Scoop to the backyards in Australia. Ian Chappell was the first Test player to use the Scoop during the first Test of the 1974-75 Ashes at the Gabba, where he impressively top-scored with 90 in the first innings. This marked the beginning of a new era for cricket bats.

It wasn’t until the next Test that Gray-Nicolls painted the Scoop its customary red. Greg Chappell used the Scoop until his retirement in 1984.

The patent on the Scoop design lasted 18 years until 1990. Once the patent was up, other companies copied the design. Dean Jones used the Kookaburra Ridgeback, a scoop copycat, in February 1990. While different variations and models superseded the original Scoop, it had its final hoorah when Brian Lara used the Scoop 2000 to score his then-world record Test score of 375 and the first-class record of 501 not out.

Before the Scoop, cricket bats had changed little in 200 years. The first cricket bat was designed in 1729 to resemble a hockey stick. Over time, the design evolved, and by the 1750s, they appeared like small rowing boat oars. It wasn’t until the 1770s that cricket bats adopted the shape and design it has today.

Willow – the heart of a cricket bat

Since my innocent youth trying to master cricket, I have spent a lifetime in the forestry industry, and my thoughts have turned to the timber used to make cricket bats. I am surprised to learn that essentially only one species is used to create top-quality cricket bats – a single cultivar of the English white willow or Salix alba ‘Caerulea’ mainly grown in Essex or Suffolk counties. It is commonly known as the cricket bat willow. It is universally agreed the best cricket bats are made from willow cultivated and harvested in Britain.

Willow’s properties make it ideal for a cricket bat. It is a hardwood, but it has softwood properties – possessing a “diffuse porous” cell structure with stiffness, density and impact resistance. While other species are denser, cricket bat willow has a similar impact resistance to tropical hardwood with a density ten times greater. It also doesn’t dent or splinter.

The bat is gently hit with a cricket ball or a mallet for several hours before being used to assist in creating the finished bat. This process is called “knocking-in”. Another important factor is a bat needs to have pleasing aesthetics and produce a satisfying sound when hitting a leather ball.

The same willow species is also grown in the Kashmir region of India, where cricket is extremely popular after British colonisation. The wood is slightly different, being darker and considered more robust, although it is more fibrous and denser, producing inferior cricket bats.

The tree was first propagated in India in the 1920s and has become an essential part of the cricket bat industry. A cheaper cricket bat is likely made from Kashmiri willow. Serious cricketers favour cricket bats from willows grown in England.

In the earlier half of last century, ex-umpire Bob Crockett promoted Australian-grown willow. The R.M. Crockett label was on bats made from timber grown on his Victorian farm at Shepherds Flats. However, in 1956, British sporting giant Slazenger bought out his company, effectively killing off the Australian willow by not producing any bats. This promptly ended the fledgling Australian industry and maintained the British hegemony.

Cultivating willow for cricket bats

Willow is planted at a spacing of 10 metres by 10 metres at 100 stems per hectare. No thinning is required but regular pruning is carried out to ensure stems remain free of branches to the crown. Pruning is carried out in multiples of cricket bat lengths, usually 3.6 metres, to secure four lengths of clean trunk.

Harvesting is from 12 years old, but usually 15-20 years, when trees reach a diameter of 140 – 150 centimetres at 4 feet 8 inches (213.5 cm) above the ground. Left too long, they become susceptible to windthrow or wind damage.

The supplier of 90 per cent of the world’s English willow is gradually running out of resources, and private landholders have been encouraged to grow trees on their land to keep up with demand.

J S Wright & Sons is the major supplier of cricket bat willow. The company started in 1894 when Jessie Samuel Wright was approached to supply willow trees to make cricket bats for WG Grace. They supply blades for hundreds of thousands of cricket bats each year.

Making cricket bats

Law 5 of Cricket (don’t ask me what it says) outlines the strict size regulations manufacturers must abide by for cricket bats.

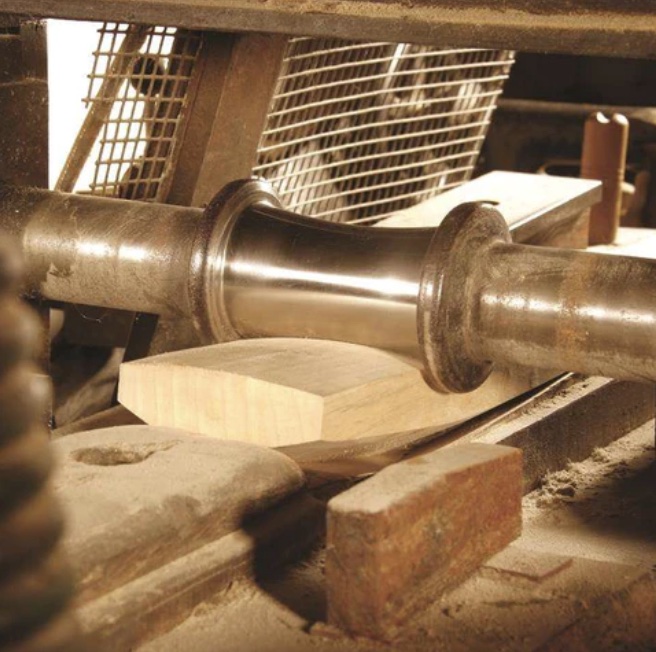

The butts of the tree are cut into 29-inch lengths and then split where bat makers assess the quality. They are then sawn to a rough shape of a bat blade called clefts. Each end is waxed to prevent splitting and air dried for up to a year before going into timber driers.

The wood is then pressed in a heavy rolling machine to shape and curve it into the blade while strengthening by compressing the fibres. The top of the blade is cut into a V shape to accommodate the handle, secured by a strong bonding agent.

The bat is then finished by hand. First, the shoulders are cut out. This is where the handle connects to the blade. The edges are sanded to create a smooth finish, and a compound wax is used to polish the bat.

Despite attempts at innovation and different timbers, the traditional willow cricket bat, with its standard shape, remains the choice of cricketers.

A prototype bamboo cricket bat with the same dimensions as a willow bat is currently being promoted. It is 40 per cent heavier, allowing for thinner bats that can be swung more easily and quicker and are supposed to have a larger sweet spot. However, there is a mixed reaction to the idea of bamboo bats. The Marylebone Cricket Club, responsible for the game’s laws, has declared the bamboo bat illegal.

The extraordinary Lillee ComBat incident

And let’s not forget the only non-wood bat used in first-class cricket – the infamous aluminium bat used by Dennis Lillee at the WACA in the 1979-80 Ashes series. No one expected Lillee to make the news for his batting.

It was called the ComBat. Graham Monaghan was inspired by the success of substituting wood with metal in baseball bats in the USA. He started a business to make aluminium cricket bats for a cheap price and target recreational cricket, schools and developing countries.

Lillee was a business partner of Monaghan’s, and he decided to use his unorthodox bat, not as a personal preference, but as a marketing stunt for the upcoming Christmas sales. Lillee first used the bat without incident 12 days earlier in a Test match against the West Indies. That was because he only lasted seven balls.

However, after four balls and one hit in the Ashes test, English captain Mike Brearley complained to the umpires. There was a distinct un-willow noise when the bat hit the ball. While the poms always maintained it was against the spirit of the game, Brearley opposed its use because he believed it would damage the cricket ball. However, the umpires didn’t tell Lillee he could not continue to use the aluminium bat. It was his captain, Greg Chappell.

Chappell noticed the aluminium bat on the morning of Day 2 when Australia continued its first innings at 8-238. He didn’t care what bat his lower-order batsman used, particularly when he happens to be your strike weapon bowler. However, after seeing a beautiful cover drive with four written all over it trickle past the pitch, Chappell became concerned that the marketing stunt was costing the team valuable runs. During a ten-minute pause in the game, as Brearley and strike bowler Ian Botham complained to the umpires, Chappell sent 12th man Rodney Hogg out to give Lillee his standard cricket bat. Lillee ignored the exchange telling Hogg to “buzz off”.

While Lillee’s stubborn rebuke of his captain was bad enough, Brearley refused to let his bowlers bowl another ball. What happened next was extraordinary and left the audience stunned. Chappell lost patience and went on the ground himself, grabbing the willow bat off Hogg and gave it to Lillee without saying a word.

Being reprimanded in public didn’t suit the fiery Lillee. He promptly threw his ComBat over Chappell’s head 20 metres away.

Maintaining his composure, Chappell walked past Lillee, picked up the ComBat and strolled back to the dressing room.

Lillee resumed his innings with his willow cricket bat, yielding three runs before being caught.

While that was the only win Brearley had on that tour, Chappell was quite satisfied knowing that his riled-up strike bowler would take his public humiliation out on the hapless English batters in their subsequent innings.

Seeing the lighter side of the incident after the match, Lillee got every player to sign the bat. Mike Brearley wrote, “good luck with the sales”. He also claims to hold a record that will never be surpassed – the longest throw of an aluminium bat in a Test match.

After the incident, the International Cricket Council revised the laws of cricket, making it clear that a bat could only be made of timber. Consequently, Monahan and Lillee did not sell a bat. In 2019, Lillee’s bat sold for £5,200 at a charity auction.

These days, it is not uncommon to see Twenty20 players use a Mongoose bat with a more extended handle and smaller surface area, which is supposed to give the hitter a larger sweet spot to score more quickly.

Despite numerous innovations, the traditional willow cricket bat with its standard shape continues to be the most popular choice among cricketers worldwide.

An enjoyable read Robert, and very interesting, thanks!

Another fantastic blog and I suspect all your sporting prowess was concentrated in your role as a master of the game of darts .

In the early 1980s, Grey Nichols tried poplar clefts for cricket bats from Mordialloc, Victoria. The bats were lighter than willow, which was considered an advantage for indoor cricket. The poplar was sourced from Bryant & May’s plantations in Yarrawonga and Tumut (ex-Snowy Mountains Authority plantations).

Thanks Rob.

From one average player to another, I had the “scoop” bat.

At best, I looked the part of a 1st class batter. The term “the sound of Willow” when the batter hit a good bowl, is one I remember vividly, as well as the distinct sound of bat to ball, ringing out across the cricket grounds.

Who could ever forget the incident with Denis Lillee and his controversial bat?

Cheers

Dave E