The day started rather innocuously on 18 March 2018 at Tathra, a serene coastal town nestled amidst the forested hills of southern New South Wales, renowned for its natural beauty near the sea. Yet, by 5 pm, this picturesque setting became the backdrop for a disaster that laid bare systemic failures in firefighting coordination, urban planning and bushfire preparedness.

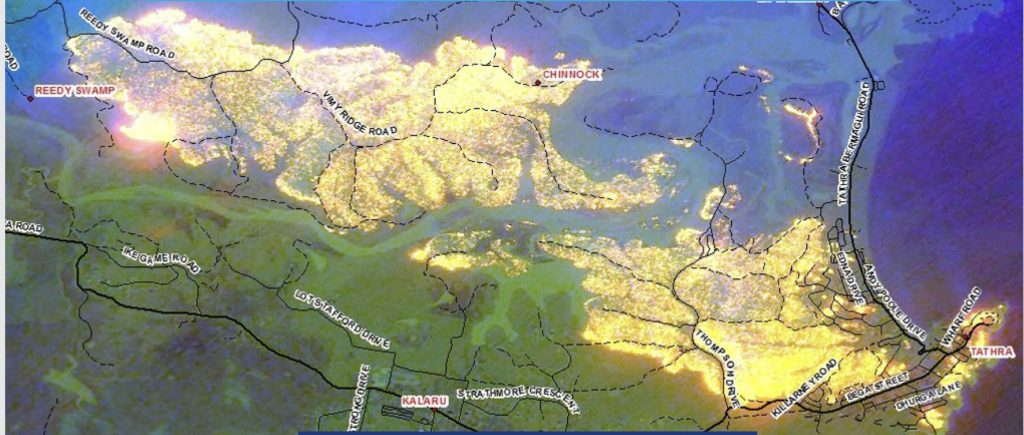

The Reedy Swamp fire, ignited by fallen powerlines and fuelled by extreme weather and high fuel loads, ripped through the community, destroying 56 homes and damaging another 48. It also destroyed 35 caravans and cabins in the Tathra Caravan Park. Luckily, no one was killed, but it left a scar on Tathra that will not soon fade.

This is a story of a preventable tragedy marked by infighting, complacency, mismanagement, and the perils of building homes too close to nature’s most dangerous edge.

A day of fire and fury

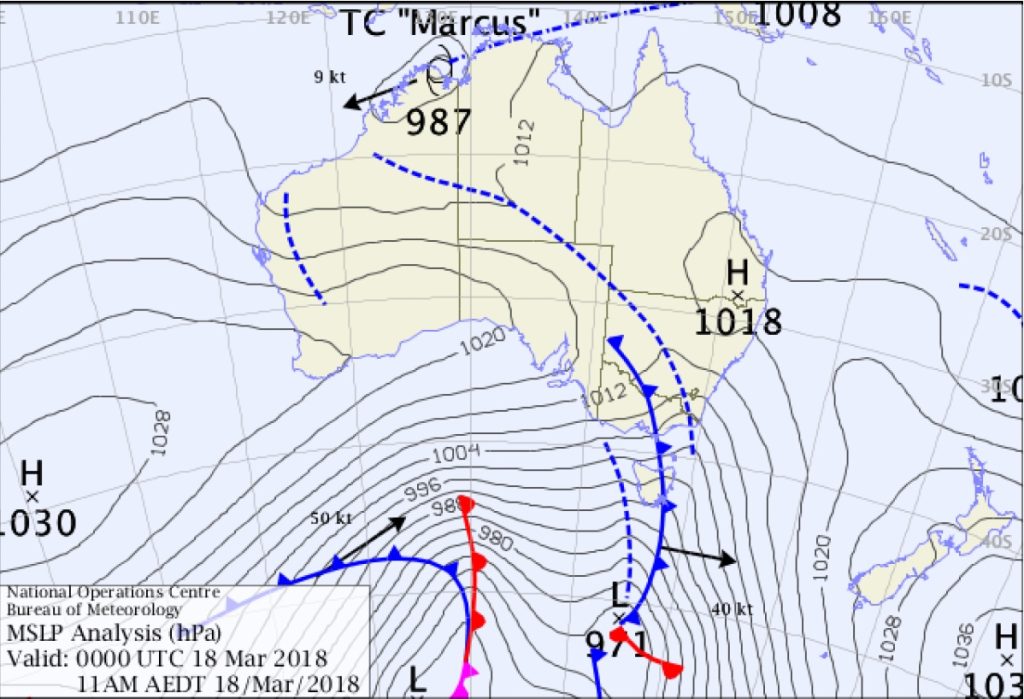

Even though summer had ended, 18 March 2018 began with conditions that every firefighter dreads: blistering temperatures, gale-force winds, and humidity so low that it seemed the air itself was flammable. Not surprisingly, a Total Fire Ban had been declared the day before.

Temperatures were as high as 12 degrees above average. It was 37.1 degrees in nearby Bega, and the relative humidity dropped to 18 per cent. The average wind speed was 35 kilometres per hour, with gusts up to 50 kilometres per hour from the north-west. By 2 pm, conditions were at their worst, peaking at 38.6 degrees, and wind gusts were up to 72 kilometres per hour. It wasn’t a good day for fire as it was conducive to spreading rapidly, particularly in areas carrying high fuel loads.

Shortly after midday, a tree fell onto a powerline running north-easterly just off Reedy Swamp Road, near the Bega River’s bank. The line fell to the ground, arced, and ignited the vegetation. What began as a small fire quickly transformed into an unstoppable force.

The forest fuels were very dry after one of the driest winters in 2017. Aided by the abundance of dry fuel and favourable slopes, the fire quickly intensified as it headed towards the Bega River. Spotting of large embers drove the fire forward, allowing it to overcome obstacles, quickly jumping the 100-metre wide river and starting its destructive path towards Tathra.

Unfortunately, the community and, indeed, the firefighters were caught off guard.

Tathra is under siege by embers falling from the sky

The initial responders were local fire brigades that arrived about 45 minutes after the start of the fire. Armed with limited resources, they couldn’t carry out a direct attack as they could not access the head of the fire, and besides, the intensity of the fire, already crowning in places, precluded any attempts at direct attack. They had to drop back and focus on containment.

They chose Lilli Pilli Road as the best possible containment line and to light a backburn. However, there was an argument about whether backburning was approved and whether it was simply a tactical burn to protect assets. Regardless, it made no difference to a crowning fire that was spotting and about to go beyond them. Not long after the backburn was lit, it immediately spotted on the other side of the road.

A retired engineer and long-time RFS volunteer, David Philp was accredited as a fire behaviour analyst. Already on standby for any Incident Management Team for the Bega area, he conducted a fire prediction analysis in the early stages of the fire after becoming aware of its existence. He produced a rapid assessment fire spread prediction map until 5 pm.

He had no access to actual weather conditions, so he based his map on average wind speeds and predicted westerly winds. Critically, while his prediction showed a slower fire spread due to lower predicted winds, he didn’t predict any spotting. Thus, his map did not show the fire crossing the Bega River. However, at the coronial inquiry, Philp gave evidence that his map showed the fire could spot over the river but to the north of Tathra, and he had only 15 seconds to brief the Incident Controller of his map.

The Council Assisting the Coroner submitted that the evidence provided suggested the Incident Management Team did not fully appreciate the extent of the risk the fire would spot across the river and the implications of such spotting. This is crucial as no attempt at an updated fire prediction was prepared at 3:15 pm after the fire had crossed the river and was impacting houses on Thompsons Drive on the outskirts of Tathra – invading the remnant forest surrounding the area locally known as the Tathra River Estate.

It is important to point out that none of the models used to predict fire spread are equipped to consider fire behaviours associated with the consequences of strong gusting winds and mass spotting ahead of the fire front. It goes a long way in understanding the tendency to underpredict a fire’s likely behaviour, which happened in the Reedy Swamp fire.

That does not mean an Incident Controller and his team should not reflect on the worst possible scenario and plan for it as best they can. Sadly, in this case, planning was coloured by a perception that the fire would not cross the Bega River. Having said that, it is problematic what could have been put in place if that scenario was contemplated, other than a futile attempt at trying to save as many properties as possible as resources were stretched that day on other fires in the broader region or, so we were told.

It wasn’t until 14:57, when a helicopter reported that the fire had crossed the river, that optimism rapidly vanished. The fire was now bearing down on Tathra. Smoke blotted out the sky, and emergency alerts belatedly urged residents to evacuate. For many, there was little time to gather more than their loved ones and pets before fleeing.

By nightfall, the fire had ravaged much of the town’s western edge that backed directly onto bushland. Entire streets were reduced to ash, and families returned the next day to find little more than charred ruins where their homes once stood.

In defence of the Incident Management Team, it appears they lacked adequate information about the fire’s behaviour, ember attacks, wind, and topography from the fire ground. Thus, they possessed a rather optimistic view of the fire once it reached the Bega River. This led to poor situation reports during the afternoon, particularly a lack of warnings. For example, the third situation report at 13:27 was identical to the previous report 46 minutes earlier.

The incident controller admitted at the coronial Inquiry that the 15:03 situation report was:

Hopelessly wrong (because) they weren’t checked carefully enough and signed off with the correct information in them.

Again, where is the accountability? This was a crucial time, as over 50 houses were about to be obliterated. The inability to properly record the likely progress of the fire and the fact that none of the situation reports mentioned the possibility of the flying embers extending beyond the Bega River during a crowning fire in heavy fuel loads under very strong north-westerly winds are very concerning.

According to Geoff Conway, a member of the Advisory Committee on Firefighter Presumptive Rights:

The reality was that the Incident Management Team was at least half an hour behind the fire in terms of their understanding of what was going on.

This is exemplified by the fact that the RFA Acting Group Officer was in Thompson Drive 32 minutes after the helicopter first reported the spot fire over the river, and no fire units were present.

The fact is, New South Wales (and every other state for that matter) does not have the resources to fight a fire or protect people and houses from a fire that can overwhelm a small town in the space of four and a half hours. Where is the accountability for that? Where is the truth-telling?

Politicians and senior bureaucrats put their faith in fancy aerial firefighting equipment as a response mechanism. Have a read of the coronial inquiry into this fire, and you will quickly realise the folly of that dependence.

Was the response to the fire adequate?

The RFS were first alerted about the fire around 12:30. They immediately sent out a couple of crews to the fire. It was a hot and windy day, and a total fire ban was declared. Yet, no machinery was on floats on standby to assist with rapid attack of any fire outbreak. Also, the RFS District Duty Officer declined offers of assistance by Fire Rescue New South Wales (FRNSW) on two occasions in the first hour of the fire. Instead, the RFS relied on aerial attack, only when it was obvious that houses were under direct threat after the fire crossed the Bega River. It was fortunate that FRNSW ignored the decision of the Duty Officer and deployed resources to the fire as they proved invaluable when the protection of houses was needed.

This was when the shit hit the fan, and RFS belatedly issued an emergency warning and told people to leave. Before that, the fire was classed as “watch and act”, whatever that means, other than supposedly properties might be affected by the fire.

Surely, within an hour of the fire, with the forest supporting very high fuel loads to the Bega River in its path, RFS should have realised that if they could not contain the fire, it was going to cause problems if it crossed the Bega River, which by then must have been obvious based on the reports from the ground indicating fire spotting ahead of the fire front.

In response to refusing offers of assistance from RFNSW after a flood of 000 calls, RFS Deputy Commissioner Rob Rogers told the Coronial hearing, while the fire was:

Burning in remote mountainous terrain, it would have been dangerous to have [Fire NSW] there.

Yet there was no pre-positioning of firefighting resources at locations where the bushland meets the houses in Tathra, such as Panorama Drive and Wildlife Drive. As the Coroner said in his report:

In fact, it appears that there were no resources in Tathra at all at the time the fire struck Thompson Drive.

Some argue, including RFS and the firefighters on the ground at Tathra, that due to the extreme fire behaviour amplified by heavy elevated fuels and the nature of the ember attack, there was no prospect that the fire’s progress into Tathra could have been averted. If that is the case, why wasn’t it realised that the Bega River wouldn’t stop the fire, and why were resources not immediately deployed to Tathra to save houses as outlined below?

Of concern is the lack of awareness and acknowledgement of the south-easterly change after 4:30 pm that was not covered in the Coronial Inquiry. The long northern flank of the fire suddenly became the new fire front. This was when most of the homes in the Tathra River Estate were destroyed. It also explains why the fire raced up the ridge to devour the houses on the other side at Wildlife Drive, Ocean View Terrace and Panorama Drive.

It is a genuine concern that RFS resources did not peak until about one hour and 45 minutes after about 50 houses had already been lost.

A response divided

In the aftermath of the fire, much attention focused on perceived or actual problems between RFS and Fire and Rescue New South Wales (FRNSW). Media reported the Fire Brigade Employees Union saying:

An ongoing turf war between the professional Fire and Rescue NSW and the Volunteer-based Rural Fire Service contributed to the losses in [the Reedy Swamp] blaze. More houses could have been saved if the RFS had accepted the initial offers of help.

It is disappointing that the animosity was so palpable that FRNSW staff were compiling a dossier of failures or sub-standard performance by a partner agency, the RFS. Even worse, the dossier was given to the media.

The dossier recorded response times to fires for RFS volunteers. One of the key performance indicators for paid full-time staff at FRNSW is their response times. They should easily achieve their targets since they are at work waiting for an emergency response. Whereas the RFS relies on volunteer staff with their daily employment livelihoods that form the priority for their daily duties, they are criticised for their different response times.

This was unacceptable, as the common enemy of the fire was overlooked because the two agencies responsible for putting out fires were distracted by finding fault with each other.

When one considers the 1994 Bushfire Inquiry, which ordered both agencies to cooperate rather than compete, one wonders what sort of bureaucracy exists in emergency management in New South Wales. As I have highlighted in numerous previous blogs about fire and flood emergencies, senior managers’ total lack of accountability is deplorable. These senior managers who run these conglomerates are showered with additional funding every time they fail and still can’t get it right. Why aren’t they held to account?

While it is easy to criticise the handling of fighting a fire in hindsight from the comfort of an armchair, reviews were carried out due to the heavy criticism the government faced in the aftermath of the fire.

One of the critical flaws that was identified in an Independent Review by former police chief Mick Keelty for the Office of Emergency Management within the Department of Justice (EMDOJ) was a breakdown in knowledge of the deployment of resources during advanced parts of the fire that hindered an appropriate situational awareness for the Incident Management Team in developing strategies to fight the fire. Remarkably, the review team could only reconcile the final resourcing sent to the fire six weeks after the event. No wonder the Incident Controller had difficulty understanding what resources were at the fire and where.

A perceived power imbalance exists in favour of FRNSW, which takes all 000 calls of all fire events and then decides whether to refer the incident to the RFS, depending upon an interpretation of which fire boundary the fire is believed to be burning within.

Notwithstanding that there is always a level of uncertainty due to absent or conflicting information during the frantic early periods of a fire where several personnel and resources are dispatched to fight a fire from different agencies, I would have thought that after 30 years of running a firefighting empire based on an Emergency Response to fires that receives additional millions of dollars after every major fire incident, that an adequate operational system would be in place. Clearly not.

Part of the problem is the overload of Memoranda of Understanding, policies and legislation that create a bureaucratic system and demarcation issues instead of fostering high-level coordination. All they have done is focus on the dispatch system on fire boundaries rather than the fires themselves. What is even more alarming or not surprising is that despite all the detailed instructive interagency policies in place, some are not followed.

The emergency services minister at the time didn’t care. He thought everything was rosy. Three days after the fire, Troy Grant had an explosive radio interview with Alan Jones. After he simply said:

The working relationship between the two (agencies), I don’t think has been better for years.

Alan Jones retorted:

You’re kidding me. You are a disappointment Troy, you’re miles off the pace! … If you were returning to a home that had been burnt to the ground and you’d lost everything, you’d want a better response than Troy Grant has given me today.

While Grant was obviously saving face and not wanting to add fuel to the fire regarding the performance of his agencies, he could have at least acknowledged there was a problem and that he was dealing with it. Instead, as per usual practice, he called for a review.

As I have highlighted in my other “Case Study in Folly” blogs, here, here and here, emergency response agencies lack accountability for not following their rules, their blatant mistakes, and the massive damage suffered from poor decisions. For example, the EMDOJ found that many agreements at the local level are totally ignored, which renders governance structures ineffective. The peak fire co-ordination committee, called the Fire Services Joint Standing Committee, failed to provide the Minister with its yearly report. This is totally unacceptable. Failures and unpreparedness are overlooked. They will never be addressed until individuals responsible and who are paid large salaries are held accountable.

As Keelty quite rightly points out:

Fire is agnostic. Along with natural disasters it gives no credence to the agency used to combat it, the jurisdiction in which it burns or to the people who respond to it. So why do we make the response arrangements so bureaucratic?

Indeed, why do we?

If you don’t manage the hazard, why allow assets nearby?

However, analysing the fire response is futile when you have parts of a settled area immediately adjoining bushland where fuel levels are not managed as a priority. Once a fire starts on a bad fire weather day in the vicinity of Tathra, then it is too late to expect to protect the residents if nothing is done to mitigate the risk of damage outside the fire season.

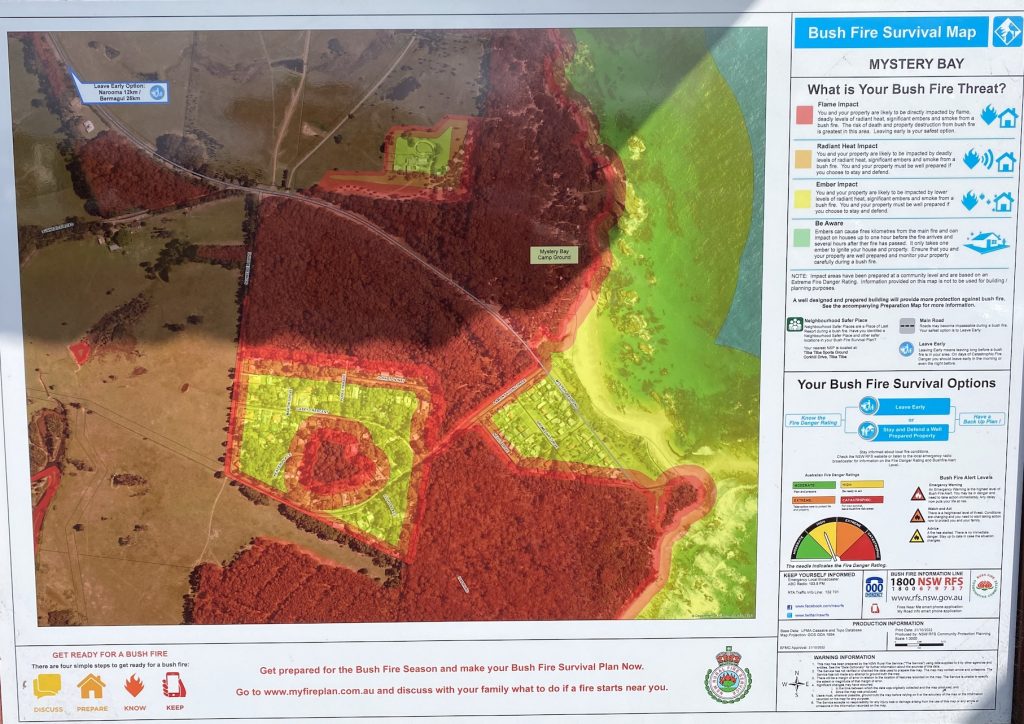

Tathra Township is a fire-prone area. It is surrounded by Crown Land forest on its western side and a national park to the north and south. It also has ribbons and patches of bushland within its borders, apparently managed as a “wildlife estate”. It is a typical peri-urban development where houses are built immediately adjacent to the forest, with no consideration to offset the development of assets from the vegetation to create some form of break. The slope angle can aid in the rapid spread of fires, making some areas a death trap.

The areas immediately adjoining native bushland to the west, such as Tathra River Estate (Thompson’s Drive), Wildlife Drive, Sanctuary Place and Ocean View Terrace, all bore the brunt of the fire.

For a place so susceptible to bad fires, one wonders why the fuel loads surrounding Tathra were not adequately managed before 18 March 2018.

According to the New South Wales Rural Fire Service (RFS):

Ninety-three fuel reduction activities in the form of prescribed burnings took place in the area from 2006 to 2017. Of the 517 hectares treated, more than half was done in the past four years.

That is just an average of 47 hectares a year. RFS claims that despite these activities, the fire was still intense.

In fact, according to evidence provided to the Coronial Inquiry, the last time any area within the now Tanja Flora Reserve was carried out was in 2008-09. However, no specific details were provided. Nothing was discussed at the inquiry about the last time the bushland reserves in town were burnt. It is clear from this evidence that the fuel levels in the dry sclerophyll forests of the reserve had reached the category of high by the time of the Reedy Swamp fire.

While the NPWS maintained that they planned to burn the flora reserve in 2018-19, no burning plan had been prepared before the fire. Evidently, the extensive forest immediately to the west of Tathra was not being managed in accordance with the Bega Valley Bush Fire Management Plan.

Until 2013, the Audit and Investigations Unit within RFS audited bushfire risk management plans and fuel reduction work for each Bush Fire Management Committee (BFMC). However, each BFMC now conducts its own audit, which essentially means it reports where and how much fuel reduction burning is carried out annually. As per Section 62 of the Rural Fires Act, there is no requirement to identify the efficacy of its work.

Despite that, the Reedy Swamp fire was so intense that it was driven by wind, and embers were sent hundreds of metres ahead of the fire front. Some argue that prescribed burning is not effective. However, RFS does not detail where and how effective these prescribed burns were. Given the ease with which the Reedy Swamp fire crowned and allowed for the fire spotting, it is doubtful any of the 93 burns were strategic enough to assist Tathra.

Professor Ross Bradstock from the University of Wollongong believes:

Multiple studies – particularly since the devastating Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria in 2009 – had shown broadscale planned burns were less effective in suppressing fire activity than work much closer to homes and other buildings. Creating a so-called ‘defensible space’, extending about 40 metres from residences was critical.

Yet even Bradstock conceded that houses in Tathra were ignited by embers driven by high winds from the crowning fire on the other side of the Bega River due to heavy, elevated fuels allowed to accumulate over many years. If fuel levels had been managed in Reedy Swamp, then the ability of the forest to carry a crown fire for such a length of time under the strong winds would have been diminished.

The problem with Bradstock’s and other academics’ analysis is that they ignore what is not widely reported about broadscale prescribed burning – few summers go by without examples of potentially devastating bushfires running into light fuels and being easily controlled. Thus, when a major conflagration occurs on the scale of Black Saturday, Canberra 2003 fires or the 2019-20 fires, where extensive areas were severely burnt, the stories and evidence showing these examples, such as the photo below, are often ignored.

The debate over prescribed burning means little in this area simply because, in 2016, the New South Wales government gazetted a large part of the Tanja State Forest as a Flora Reserve under Forestry Act 2012, along with larger areas of the Mumbulla and Murrah State Forests further north and a similar area of the Bermagui State Forest further south. In a unique arrangement, the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service were appointed to manage these reserves, primarily set up to:

Conserve the south coast’s last known koala population.

Unfortunately, the management plan for these reserves and the adjoining Biamanga National Park, Bermagui Nature Reserve, and Mimosa Rocks National Park states that fires are a major threat to koalas. The intention was to carry out prescribed burns in small patches only surrounding areas of koala activity. Instead, the focus was to have a strategic fuel reduction zone on the western edge of the new reserves and enact little fire management within them. Less than two years later, we saw the folly of that strategy ever working.

Why isn’t more burning carried out?

Every Federal, State, and colonial inquiry between 1939 and 2003 recognised the lack of prescribed burns as the major contributing factor to the intensity, spread, and damage caused by major bushfires. Prescribed burns do not prevent wildfires, but they do help mitigate the potential threat to life and property.

There are 22 million hectares of bushfire-prone land in New South Wales; this century, not even one per cent receives fuel reduction treatment annually. To deflect from this problem, politicians, bureaucrats, activists, and many academics try to blame climate change and rising temperatures for the destructive fires. However, as the Reedy Swamp fire clearly showed, a few degrees in temperature will not make a big difference because the fuel levels on a bad, windy day create a terrible fire risk.

Residents and members of the local bush fire brigade claim the system for organising a fire reduction burn is overly bureaucratic, weak in direction, and exceptionally poor at achieving effective outcomes. To organise a burn, an inter-agency committee prepares plans for it, and many preconditions must be met before any action can be taken, severely limiting the days available to conduct the burn.

One of those preconditions is dictated by the Bush Fire Environmental Assessment Code, which prioritises threatened species. This is why prescribed burns are delayed, especially given the focus on koalas and the belief that a low-intensity cool burn is deleterious to them.

It is high time that fuel management objectives are prioritised over perceived ecological imperatives; otherwise, houses and lives will continue to be threatened and destroyed.

The most difficult problem is the availability of volunteers, who require at least a week’s notice to get permission to take time off work. Pressure is then applied to carry out the burn on the specified day, even if local weather conditions and on-ground factors are not ideal or favourable for achieving the burn’s outcomes. This invariably leads to burns being called off until another year and rarely undertaken.

Consequently, fuel loads in many parts of the South Coast have been permitted to develop to very high levels. The current system for planning and carrying out prescribed burns is not fit for dealing with the threats posed to many isolated settlements on the South Coast surrounded by forests to their west, such as Tathra, Potato Point, Lake Conjola etc.

If prescribed burning is too difficult because local brigades lack experience and confidence and red tape is too constrictive, then perhaps a more effective fuel reduction strategy closer to the houses is mechanical fuel load reduction.

Worse, policies limiting vegetation clearing near homes, while well-intentioned, leave residents exposed. Although the risk of building so close to the bush has been known for many years, planning decisions continue to favour aesthetics over safety.

I recall my time as a northern New South Wales forester in the early 1990s. The state government and local councils held planning days for the public. The focus was on Sydney’s bourgeoning population and the strategy of getting people to move to major regional centres such as Port Macquarie, Coffs Harbour, and Ballina on the north coast. They promoted this idea by highlighting the opportunity to live near nature surrounded by the local state forests.

I highlighted to the town planners the risks of this strategy and the foolishness of placing assets near fire-prone forests, which would have exacerbated the threat. They didn’t even have any policies in place to force new houses to be built some distance away from the forest to give firefighters and residents a chance to reduce the risk of fires destroying their homes. The town planners expected trees to be cleared and fire breaks in the forest to provide that level of protection.

That naivety shown by town planners and bureaucrats was across the whole state as places on the south coast, such as Tathra, were allowed to develop immediately adjacent to fire-prone forests.

The aftermath of the Reedy Swamp fire underscored the need for stricter zoning laws, more resilient building materials, and reconsideration of what it means to live in bushfire-prone areas. We have learnt from this fire that within 40 minutes of impacting Thompson Drive, after 3 p.m., almost simultaneously, the whole landscape was alight, and the fire was burning in locations several streets beyond the interface a further 30 minutes later.

Given RFS Deputy Commissioner Rob Rogers’ comments to the Coronial hearing, quoted earlier, it seems ludicrous all government agencies allow a settlement to develop, particularly newer ones in recent times, carved out of the bushland, where a known threat of fires to the west under severe weather conditions, can make it impossible to control unless the fuel levels are meticulously managed, which clearly, they were not.

The patch of forest between the Bega River running towards Thomson Drive is a dry sclerophyll forest community. According to the Bega Valley Bush Fire Risk Management Plan, the Tanja Forest Flora Reserve is a dry sclerophyll forest, and the minimum period for no fire is five years, but occasional intervals greater than 25 years are desirable. A long fire interval may be desirable to a bureaucrat too lazy to implement an active fuel management program. Still, for residents of Tathra in the path of a fire raging through that area, that sort of interval is inconceivable.

A fire in a forest carrying up to 7.5 tonnes per hectare can be managed and attacked directly because it produces only 300kW per metre of fire front. In eucalypt forests, fuel loads build up at roughly two tonnes per hectare per year. Thus, fighting fires under severe and extreme conditions becomes problematic if no treatment occurs in four to five years.

Did climate change play a role?

A lot of people, particularly the government, agencies and bureaucrats, are quick to point the finger at climate change as the primary reason for such devastating fires. They claim the dry winter is one of the driest ever, ignoring weather records going back over a century. Sure, 2017 was dry and was one of the driest years for a while. But there have been much drier years in the past.

The fact is this fire occurred during the normal period of the bushfire season, which extends to 31 March each year. It was also autumn when the weather conditions were not exceptional. Mr Smyth, on behalf of Insurers and residents, told the coronial inquiry:

This fire cannot be characterised as an inevitable consequence of climate change or drought. The fire ought not be seen as a consequence [only] of the weather on the day, or any natural organic process of the bushland in which it ignited.

History has shown that there is a build-up of fuel levels, then big fires will occur in late March or at any time of the year. For example, in March 1965, the Chatsbury-Bungonia Fire burnt 90 kilometres from north of Goulburn to the coast near Jervis Bay in one day, and the Tumut River Fire burnt from the Tumut River to Eucumbene Dam. In March 1985, a fire swept from Bodalla to Potato Point under hot, westerly winds

The Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) has undue political influence by directing the governments to focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and not reducing fuel levels. Former ACT ESA Commissioner Major General Peter Dunn boasted in the aftermath of the Tathra fire:

We advised Federal Climate Change Minister Chris Bowen that ELCA wanted a 75 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030 (below 2005 levels) and will be holding the government to account on ratcheting up ambition.

The problem with this attitude that seems to escape Major General Dunn is that even if the government reaches this impossible target, the climate won’t change. The occurrence of devastating bushfires has nothing to do with climate change. The intensity of fires depends on fuel and weather. Despite Dunn’s hope, humans cannot control the climate. We will still get hot summers, and high fuel levels will still pose a problem, particularly for built-up areas that immediately adjoin forests. So, the real question ECLA should be asking of those responsible for managing the forest areas is: What is being done to keep fuel levels at a manageable and safe level?

Mr T Smyth, on behalf of Insurers and Residents, summed up eloquently at the coronial inquiry:

To be clear, this fire cannot be characterised as an inevitable consequence of climate change or drought. The fire ought not be seen as a consequence (only) of the weather on the day, or any natural organic process of the bushland in which it ignited.

Postscript

In February this year, I spent a week in Tathra, walking through the scars of the 2018 fire, examining the bushland that envelopes the town, and speaking with locals. What I found was deeply troubling.

Denial hangs over the town like a smokescreen. Houses remain vulnerable, sitting in the direct path of inevitable destruction when the next severe fire weather day arrives. The residents seem oblivious to the towering danger surrounding them—unchecked fuel loads in the forests that cradle their community like a loaded gun.

One resident of the Tathra River Estate recounted how his house survived the firestorm. Armed with foresight and determination, he spent hours dousing his home and garden with water that morning. His vigilance saved his house. But in the chaos of his escape, he narrowly avoided losing his life as the inferno engulfed his street. Around him, twelve homes were reduced to ash. His story starkly contrasts others who had neither the knowledge nor the opportunity to act.

And yet, the forest mismanagement that exacerbated the 2018 catastrophe continues unabated. In seven years, I have seen no evidence of fuel management in the forests surrounding Tathra. The areas that escaped the fire are now ticking time bombs, laden with fine fuels and choked with overcrowded, diseased trees struggling for survival. This isn’t healthy bushland—it’s a powder keg waiting for a spark. The bellbirds, with their melodious sound, are a mournful anthem to the sick and neglected state of the forests.

The photo below, taken at nearby Mystery Bay, highlights the bushfire risks residents face. However, it conveniently overlooks the responsibilities of forest managers and land owners in ensuring public safety.

This negligence is a failure of governance, and it cannot go unanswered. The agencies and individuals responsible for managing these forests—the RFS, the local council, the state government, and the local Aboriginal Land Council—must be held accountable. The residents of Tathra must demand action. Waiting for the next inferno to strike is not a plan—it’s a death sentence for homes, livelihoods, and possibly lives.

It is too late to save a town when a ball of fire is rolling towards it. Bushfire prevention starts outside of fire season, during milder weather, with a clear-eyed commitment to fuel management and forest health. Green initiatives and climate change discussions are important, but when they lead to inaction and forest mismanagement, they put lives at risk. This is not an abstract environmental debate—this is life and death.

Tathra’s residents also need to take responsibility for their safety. Many lack the basic knowledge of preparing for or responding to a bushfire. Education and preparedness must go hand in hand with proper forest management. Without both, another 2018 fire is not just a possibility—it’s an inevitability.

The Black Summer fires shortly after in 2019-20 demonstrated this. A lack of swift action early in the fire season to extinguish fires led to them exploding across the landscape a couple of months later when severe fire weather arrived. The south coast was badly hit, from Mallacoota to Batemans Bay. Homes were buried in dust, and livelihoods were destroyed by flame. Settlements such as Mogo and Conjola Park were nearly wiped off the map in one afternoon of hell.

The time for lame excuses is over. Action is needed now before Tathra becomes another tragic case study in preventable bushfire destruction.

I was a forester in NSWFC during the Ash Wednesday fires that burnt from Victoria, south of Bombala, to the great eastern fire break. It completely destroyed the Tennyson Creek Flora Reserve in Bondi SF, and the equivalent cool temperate rainforest south of the Border.

It had been estimated that there had been no fires in this area for at least 500 years, hence no eucalypts and the designation of a rainforest. We were permitted to put a D8 south of the border to protect Bondi SF pine plantations immediately next to the border and Tennyson Creek. The progress of the D8 was one blade width x 100m per hour, such was the density of the trees and understory, such as sassafras and blackwood, etc. but no eucalypts. Obviously the trees were very large.

After the fire, everything with a DBHUB of less than 1.5m was totally consumed and the forest floor resembled a gravel pit.

The fire then hit E. nitens and E. fastigata forest some of which had diameters over 2-3m. The fire really took off and went to the coast with embers and ashes reaching as far as Bega and beyond.

The pine forest actually slowed the fire down, and some US mathematicians came out and calculated flame intensities that had never been recorded elsewhere.

How do I know this, I was the fire boss in a helicopter, having been unofficially advised by the RAAF in Sale that a massive wind shift at 100kt was coming our way? I was in a helicopter, and flame heights went from 5 metres burning into a nor-wester to about 400m with a convection column up to 50,000 ft, confirmed by a commercial pilot.

The helicopter pilot took fright and dropped me at Bondi Nursery, where I was among about 200 Vic Forests and NSWFC personnel on immediate evacuation alert.

I was at the tail end of the column, and no one was even slightly injured.

My point is that such fires as this, 1939 in SE Aus, 1967 in TAS, 1972 in WA, etc., were equally as severe, yet the media and politicians talk about mega-fires caused by climate change. What a load of crap.

In those days, the NSWFC were the determining authority, and we were trained in our degree at ANU by the likes of Phil Cheney et al. I might add, Phil became a friend and came to every fire at Bombala since then and we had some beautys.

Any cabinet submission or academic paper submitted today regarding fire management in the Australian forest landscape ought to contain Gary Squire’s (via Michael Ryan) photo from the 2019-20 fires in Victoria. It clearly demonstrates the benefit of fuel reduction burning.

Once the crown fire reached the forest with lower fuels it quickly went out.

It is patently obvious surely to leathered pollies, green narcissists, and water fleet commodores.

Robert, you will no doubt include this in your next awaited response to the ‘lock it up, let it ignite’ cohort.

I forgot to add that the Rural Fire Service is a non-professional amateur body with not nearly the amount of training and experience we had as foresters.

I was also a brigade captain in Tumut during the 2003 Canberra fires, and we were the only brigade that actually controlled fires on the night of the lightning storm.

Ray,

You should do an article on your experiences in 2019 and 20.

Did you get any photos of those flame heights?

John

With 40 years of experience in forest management and rural fire, with emphasis on the use of fire for land management and wildfire control, it has been my experience that the introduction of the Incident Management System (IMS) has allowed fire control to be driven by operators with “technical” qualifications and little if any practical experience or knowledge of wildfire behaviour.

The blind belief that algorithms can predict fire behaviour based on past experience or arbitrary inputs has lead to a an ‘Escalating commitment to failure.”

Unfortunately, the Incident Controller, through ignorance or arrogance, believes the computed information (predicted) over that of the fire ground report (real time), leading to the incorrect allocation or absence of fire ground resources.

We are adjacent to Bournda Nature Reserve on the northern side for 2 kilometres. The nature reserve joins Bournda National Park and local Aboriginal Land Council land and Crown land, all up approximately 12,000 hectares of bushland. Most of this land has had no fuel reduction for over 50 years.

There was an attempt to burn along our boundary and some other neighbour’s boundaries, but it failed due to rain falling the evening it was lit. Except for some other small hazard reductions of either a few hectares or 200 square metres, basically in the Merimbula/Tura Beach area, and a few lightning strikes, there has been no hazard reduction for over 50 years.

This large chunk of bush joins Tathra on the southern side and Merimbula/Tura beach on the south/ east side, Bournda on the eastern side, and Wolumla on the south/west corner.

There is very limited access to Bournda Nature Reserve, land council land and Crown land in the event of a fire, as they used to access the areas mentioned above through a neighbouring property and our property till the next-door neighbour was allowed to subdivide across our old access through her property, which is on flood-prone land. This access used to enable access to Bournda Nature Reserve on the northern side in 10 minutes.

My dad tried for years, pushed hard for fuel reduction, until he passed away. I now look after the property for my mum (who hasn’t been in the best of health for many years). I’ve been pushing for fuel reduction since my dad passed away, and had many emails and meeting and phone calls with the manager and ranger for Bournda Nature Reserve and been told they are going to attempt to do some fuel reduction in 2025, but I seriously doubt that it will happen.

I asked for their plan in what area they are proposing to burn, but they won’t give me that information, and I believe that they don’t have one, and that’s the real reason they won’t give me it.

I’ve also given the RFS a serve about pushing for fuel reduction and took them for a drive and a look about. This occurred when I was getting some HRCs for my mum’s property – Harry was his name from Batemans Bay.

I was told that he would report back to some fire committee about it (that was approximately 2 years ago).

I’ve put posts up with videos on TikTok about fuel loads in Bournda Nature Reserve and linked these TikToks to Facebook.

All I can say is that if this area catches on fire on a 40-degree day with a hot north/west wind, it will wipe out the places mentioned above, plus other adjoining localities, and if we get a southerly change, it will attack Tathra from the southern side.

I have lived here for 63 years. It’s only a matter of time before this happens!

Wayne, thanks for your comment – it is a real horror story.

I was appalled at what I saw when I visited your area in January this year. All the settlements from Eden to Ulladulla are a ticking time bomb because they flank bushland to their west, which isn’t properly managed.

I suggest you contact your house insurance company and alert them to what you have been trying to achieve. The Insurance Council may be the only option to make representations to government and bureaucrats; they have a legal responsibility to protect residents.