Unconfirmed reports from seagoing fishing parties suggest that Fraser Island is again suffering considerably as a result of bushfires which some say are raging from the island’s “stem” to its “stern.” Maryborough Chronicle, Tuesday 5 February 1952

I have decided to bring this blog forward ahead of others I have already written for several reasons.

Firstly, summer is around the corner, and large parts of eastern Australia are still dry and suffering drought-like conditions. Fires that started in spring this year have been allowed to continue burning. Combined with fires that start during severe fire weather conditions in the peak of summer, both types of fires could lead to more massive conflagrations, particularly in areas that escaped the carnage of 2019-20 Black Summer fires.[1]

Secondly, the Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Arrangements (RCNDA), set up to primarily look into the responsibilities and coordination between the Commonwealth and State’s emergency response to natural disasters, has just released its findings. Its primary focus was the 2019-20 Black Summer fires. Predictably, the report ignores submissions made by professional foresters who advised how forests and fire management can be improved in Australia; how the emergency response model is failing Australians and our forests; and how we can avoid the bushfires of last summer if our forests are actively managed at a landscape level.

The cause of bushfires has nothing to do with climate change and more to do with the absence of an active forest management system based on forest science, and infrastructure to support a rapid response to fires. These management systems were in place after World War II before they were progressively dismantled during the nineties and noughties, even though they worked in the past.

By now you would have seen media reports about a large bushfire on Fraser Island, threatening major tourist facilities. During late October we went to Fraser Island and stayed at nearby Hervey Bay afterwards for a couple of weeks. During that time, we had a bird’s eye view of the smoke emanating from fires on Fraser Island.[2]

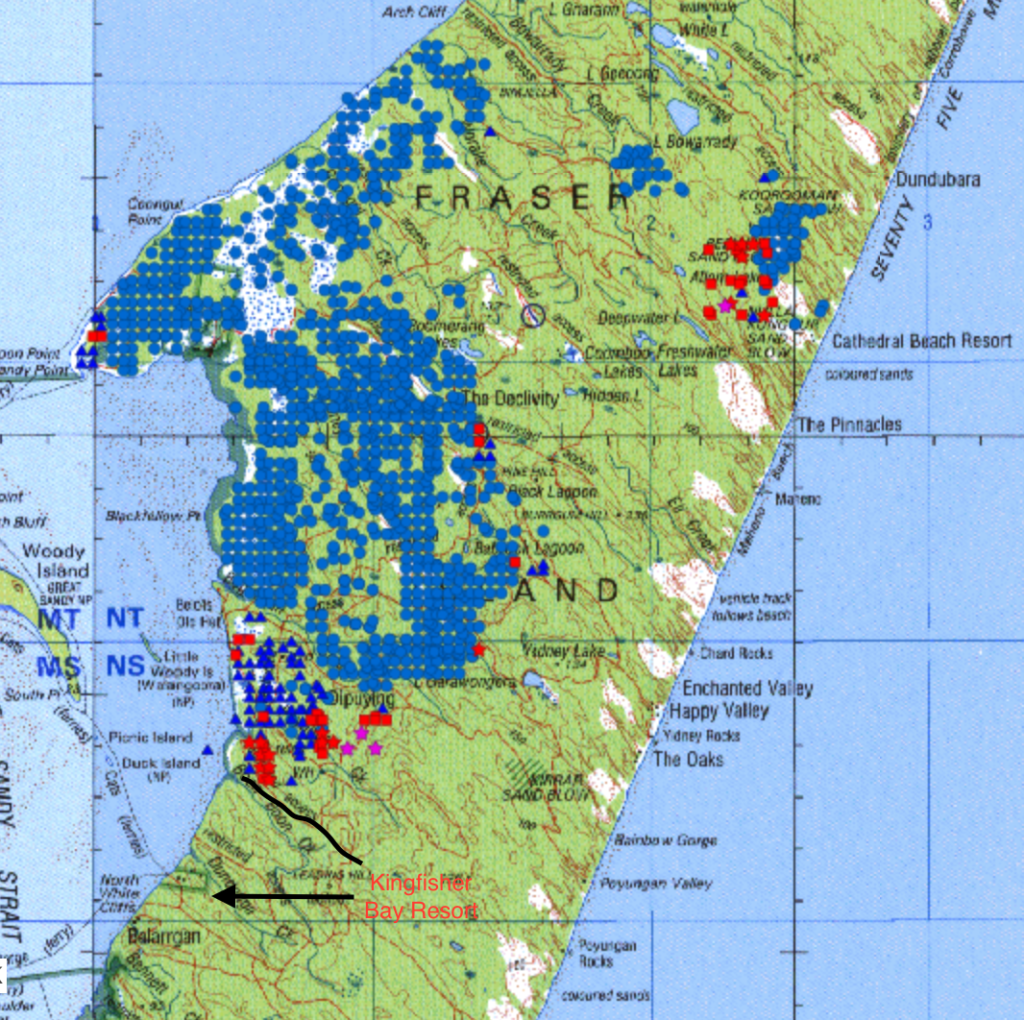

An illegal campfire was the cause of a small bushfire on 15 October near the northern tip, or stem, of the island. It was left to its own devices and spread under prevailing winds. Hot weather and strong northerly winds in mid-November turned the elongated south-western flank of the fire into a threatening front that has engulfed forest to the south. The fire has spread south under northerly winds, and by 2 December, the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services (QFES) reported that the fire had burnt more than 80,000 hectares or a little over 45 per cent of the island. The fire now threatens Kingfisher Bay Resort on the west coast, and Happy Valley and Cathedral Beach Resorts, adjacent to Seventy Five Mile Beach on the east coast.

When I was on Fraser Island for four days from 26 October, I saw QPWS staff driving along the beach and near Central Station, nowhere near the fire. They were not carrying slip-on fire-fighting equipment, and there clearly wasn’t any priority to direct staff towards fighting the fire. QPWS reported that the fire was in inaccessible country and difficult for firefighters to access. When I climbed Koorooman Sandblow at sunset, while staying at Cathedral Beach Resort, my photos were made more spectacular by the nearby smoke plume.

The Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) have sat back and watched the fire burn under mild weather conditions from an abandoned camp fire into 80,000 hectares. I believe QPWS did not consider deploying a bulldozer or skidder to construct tracks around the fire to allow crews to access to put the fire out. This action should have been done under the favourable weather conditions immediately after the fire started in mid-October. It would have kept the fire to a tiny area, and no-one would have known anything about it.

There is a system of tracks that should have been used or re-opened to contain the fire once it first started spreading south in mid-November.[3] In the late 90s, a forester working for the Queensland Rural Fire Service was in charge of a back burn from Dundubara on the eastern beach to Awinya Creek on the west coast, along an old logging track to stop a fire travelling from the north. Firefighters cut down banksia and ti-trees to a distance of ten metres either side of the track. A dozer cleared the fallen debris into the burn zone. The fire was stopped at this fire trail under similar weather conditions today, without the use of any aircraft.

Suppose a fire starts on private property and is left unattended and subsequently damages adjoining land and assets. In that case, the landowner could face prosecution and would be liable for the damages caused. Yet we see a government agency that wilfully ignores a fire which now threatens valuable private assets, including the iconic and world-class Kingfisher Bay Resort. Before the deteriorating weather conditions at the end of November, QPWS finally took action. Rather than attacking the fire on the ground using firebreaks and back burning, they deployed water bombing aircraft that have dropped over a million litres of water to no avail.[4] Water bombing long fire-fronts looks good on the television news but has little chance of success. QFES reported they had ‘emergency crews’ mapping the likely spread of the fire. The promotion of this sudden and misplaced response by QPWS and QFES is an attempt to win our gratitude and portray their inadequate response in a favourable light. They are trying to show they are doing something to control a blazing wildfire by emphasising the illegal camp fire, even though their inaction has contributed to the fire becoming so large and damaging for the environment, threatening tourist resorts and ruining holiday plans for visitors.

Mainstream media have reported billowing smoke from Fraser Island that has sent plumes of smoke south over Brisbane, causing city-goers to complain of the smoke hazard.[5] QPWS and many environmental groups and activists believe that any machinery used in a forest is destructive and irreversibly harms the environment. Yet, ignoring fires and allowing them to spread to the size of a million football fields is a national disgrace and tantamount to wilful and negligent land management. Where is the accountability for QPWS mismanagement, especially when you consider that a rapid response to the fire would have prevented, what QPWS are now admitting, an impact on the wildlife and the environment? No competent land manager allows a fire to remain uncontained immediately prior to the fire season.

Last week hot northerly winds returned to the region with very high temperatures and low relative humidity. More than 75 firefighting personnel, 21 aircraft and more than 30 fire trucks have now been deployed to fight the large fire. Residents and staff of the island were told to prepare to leave. Incredibly, QFES and QPWS have now admitted there are high fuel levels, a damning admission of the neglect of nearly 30 years of management. Tourists were banned from the island from 5 pm on Saturday 28 November, until further notice, ruining their Christmas holiday plans and threatening the economic livelihood of the tourism facilities, already reeling from COVID lockdowns and restrictions earlier in the year.

Why was the response so late when conditions favoured the easy containment of the fire? Why has so much of the island been allowed to burn under more severe weather conditions? For example, as I wrote this blog, I looked at the North Australia & Rangelands Fire Information website (FireNorth). I can see many east-west fire trails to the south of the current fire front which could have formed the basis of preventing the spread of the fires south towards Kingfisher Bay Resort and Happy Valley. Since 1992, when QPWS took over management of the island, fuel levels have been allowed to build up, and the roads and tracks have deteriorated. Many old tracks and firebreaks have been allowed to overgrow and are now closed. Instead of using firefighters and machinery to open firebreaks, QPWS have waited until the fire has become dangerous, and they now rely instead on expensive water bombing techniques that are doomed to fail. A spokesperson for QFES and QPWS told the media that “it is difficult to fight fires on Fraser Island…access and topography is difficult. It is a sand island and that is making water bombing difficult”. It wasn’t that hard during forestry management days once they put in place an effective fire management system. It seems evident that even if QPWS staff responsible for the management of Fraser Island have fire knowledge and experience, they are not allowed to use it despite a plethora of recorded fire management and research that the Forestry Department produced over many years. Why hasn’t the government consulted retired foresters, who between them, have many years of experience working on the island? They know the area much better than QPWS and the emergency crews, and can provide advice on how to manage wildfires on the island.

Fires have always been a feature of Fraser Island. Aborigines lived and hunted on the island using traditional fire practices that kept the forests open. A forestry officer reported that he could ride his horse through the tall forests during his inspections before the 1950s. Over time, however, things began to change with more human presence on the island and the an increased outbreak of unwanted fires. Managing fires on the island has always been a challenging task. Following the fires reported in the Maryborough Chronicle in 1952, the Forestry Department introduced a fire plan and became more active in fire management and prevention. Timber producing areas were protected from fire by roads, tracks and a series of firebreaks, and were divided into burning blocks of several thousand hectares. These firebreaks were brushed with brush hooks, then left for a few weeks to dry and then burnt in the colder months. Foresters burnt each block on a rotational basis every three to four years. Researchers carried out experiments on appropriate frequencies, and prescriptions were developed and refined. For example, researchers found that wildfires did not burn through areas that had been burnt up to three years previously. The result was that the southern two-thirds of the island, under forestry management, were protected from severe fires, and no longer was the island alight from stem to stern. The forests were in such great shape from this active management that a 1990 Inquiry recommended that the State Forest become a National Park for its extraordinary natural values.[6] Since the change-over of control to National Park in 1992, forestry firebreaks have either been closed or allowed to overgrow. Various sources have advised that QPWS do not keep any fire-fighting equipment on the island and do not maintain any firebreaks.[7] In the northern section of the island, dedicated a National Park since 1973, no tracks have been built at all. This means that QPWS have no intention to conduct a fuel management program across the broader landscape. Consequently, small fires that could so easily be attacked and extinguished, now morph into more massive, destructive fires all too frequently. I know I speak on behalf of a lot of foresters from Queensland who are not surprised at the current fires and the associated comedic response from the current managers.

The Forestry Department regularly maintained all of the tracks. One of the significant problems with sand tracks is the movement of loose sand after rain events which eventually lowers the road surface and leads to ‘box-cuttings’ which exacerbate the problem, as water has nowhere to go. I saw a number of these on the island, and one was at least three metres deep! I also saw numerous examples where QPWS have not maintained the major roads at all. Sand along the edge of the tracks has prevented water from entering mitre drains. During forestry management, road maintenance was an essential function, not only to ensure roads were trafficable to log trucks, but to prevent environmental degradation. In the early days, horses or oxen dragged a ‘delver’[8] to bring sand back onto the road. Afterwards, a large steel bullock tyre dragged along the road smoothed out the lumpy surface. In the 1950s, a small dozer towed a grader on four steel wheels. From the 1960s, a little grader was used to bring the sand built up on the road edges back onto the road. This regular maintenance prevented the severe erosion of the roads and tracks we see today.

Professional foresters are calling for QPWS to prepare and implement a specific fire management plan and strategy which includes an adequate firebreak system across the whole island and an active fuel reduction program. The government needs to allow QPWS staff (particularly at the management level) to practice prescribed burning techniques and fire suppression on the ground so that they have the confidence to deal with the inevitable fire management issues and not rely solely on aerial burning and water bombing. Aerial surveillance should also be carried out during periods of high fire danger, particularly when thousands of campers are spread out around the island.

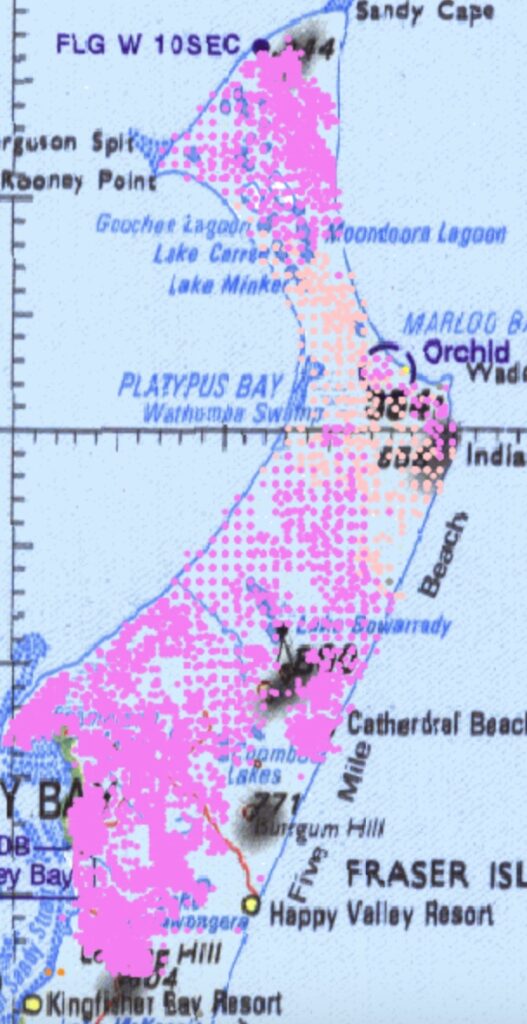

The Fraser Coast Mayor and tour groups have called for an inquiry into why over 80,000 hectares has burnt, much of it for a month before any major control action was undertaken. Initially, the Queensland government defended QPWS when Environment Minister Meaghan Scanlon claimed that 13,000 hectares per year was burned on the island. She said four planned burns occurred this year at Orchid Beach, Happy Valley, Ocean Lake South and Kingfisher Bay. Clearly those burns weren’t too effective as aerial water bombing has turned to protecting Kingfisher Bay Resort and it has been reported that Happy Valley is in the fire path under the northerly winds. A back burn immediately adjacent to Cathedral Beach Resort was carried out to save the camping area.

On Wednesday 2 December, the Premier directed the state’s Inspector General for Emergency Management, Alistair Dawson, to conduct a full review of the bushfire and examine all aspects of the preparedness and response to the blaze. Unfortunately, these government-run exercises only result in shifting the blame elsewhere and ignore the key issues. Already, QPWS is blaming the mess on illegal fires lit by campers and the difficulty of access. Yet if campers had access to light a fire, why didn’t QPWS staff use the same access, whether by boat or land, to immediately attack the small fire? The other default blame will be climate change and therefore those responsible for allowing this mess to develop as it has will be able to avoid any scrutiny and accountability.

What will it take for change to occur – people being killed or a world-class tourism resort burnt to the ground? Don’t hold your breath as the RCNDA endorsed the 2004 Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management. That report effectively ignored the 2003 Select Committee Inquiry into the Alpine fires which endorsed active land management of the forests, including a greater emphasis on prescribed burning across the landscape. Instead, COAG supported the emergency response and evacuation model we see today which has seen hundreds of lives lost and thousands of homes destroyed from mega-fires in the last 20 years. The only beneficiaries of this deficient system are the empire-building fire chiefs, their supporting bureaucrats and the green academics that monopolise research funding towards their dubious fire science modelling.

Meanwhile, for Fraser Island at least, we can be certain that the old days have returned with fires from stem to stern. I wouldn’t have the confidence to book a visit during the fire season under that scenario.

[1] One little known fact from the 2019-20 Black Summer fires is that a lot of the fires started in October under fairly mild conditions and should have been attacked and controlled early. This is not unusual as a lot of ‘cocky’ fires are lit as late as they can get away with to get as hot a fire to promote green pick. It’s just that if you leave uncontained fires to coincide with the end of a drought period when the soil and fuels are very dry, we see large mega-fires develop easily during severe fire weather conditions.

[2] I have a particular soft spot for Fraser Island. I have visited the island a few times for recreation, but also for work. While still at school in Maryborough in the early 1980s, I spent time camping and following Hyne and Son supervisors on their rounds visiting the logging operations. As a forestry student, I returned for three weeks in February 1986 to assist in brush box (Lophostemon confertus) and satinay (Syncarpia hillii) regeneration surveys. While at university, I wrote a number of elective essays on Fraser Island covering silviculture and sand mining. My knowledge of the sand mining and subsequent rehabilitation nearly got me a job as a forester with Alcoa’s bauxite mining operation in Western Australia after graduation.

[3] In fact, there are a number of east-west trails across the island further north that should have been used to prevent the spread of the fire south. For example, Wathumba Road from Orchid Beach to Wathumba; Awinya Road and Management Track from Dundabara to Awinya Beach; Woralie Road from The Pinnacles to Woralie Beach; and Moon Point Road from Happy Valley to Moon Point. I do not know the current state of those roads but some of them may be closed due to the lack of maintenance and a policy of closing tracks.

[4] QFES tweeted on 29 November that in “two-and-a half hours, three Fireboss fixed-wing aircraft dropped 84 loads of saltwater on the fire. That’s 250,00 or one 3,000-litre drop per aircraft every five minutes”. This was supposed to impress the public about their fire-fighting capabilities. However, what they failed to point out was the futility of the exercise as it did nothing to quell the fire front. Nor were they forthcoming in how much this pointless exercise cost the tax-payer. Admitting defeat, the next day the message was focused on water bombing around Kingfisher Bay Resort to slow the advancing fire.

[5] On the morning of 24 November I was in Brisbane on my way back from a short trip to Tasmania. I recall leaving my hotel room and the atmosphere was thick and pungent with smoke from fires. I later found out it was smoke from Fraser Island.

[6] The Commission of Inquiry into the Conservation, Management and Use of Fraser Island and the Great Sandy Region, 1990. The Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO) under John Sinclair even wanted the new area declared a World Heritage, such was the exemplary forestry management which not only protected the forests from unwanted and destructive fires, but maintained other equally important flora and fauna values.

[7] A source who has relieved as a Ranger on the island bemoaned the lack of road and track maintenance and the closing of access tracks. He also remarked that some of the rangers acted like they wanted a six-gun on their hip. How that helps in fire management is anyones guess.

[8] A ‘delver’ was rectangularly shaped wooden frame plus a right-angle triangle to make one side longer than the other. A blade was fitted to the angled section on the front, essentially similar to a grader blade. It was designed to bring the sand towards the centre of the road to fill in the holes.

Well said Robert.

“As always saying it as it is. “

Well done Robert. This needs to be said and shared. Current land management in this country is failing terribly and ‘sorry’ is no longer enough.

Firstly I should say thank you Robert Onfray for highlighting the incompetence of this state government and lack of care for anything outside the metropolitan area.

I have many points of concern about the government approach, so I will just highlight a couple.

Even for a medium sized property or area with any sort of agriculture, keeping no firefighting equipment would be regarded as incompetent or negligent. The same comment applies to tracks and firebreaks.

This is not the first time an island fire has been contained on a peninsula for an extended period but no machinery has been brought in to clear a break or a series of breaks.

Possibly as concerning is the spin put on the lack of accessibility, the great efforts being made by the aircraft and the excuses offered as to why they don’t work.

Even after last Summer the green mantra seems to be prevailing. In fact they have doubled down and managed to convince some governments that koala habitat needs to be replanted.

It is not habitat that we are short of. It is common sense.

Great Blog Rob. The “lock it up and leave it “ management approach, has not and will not be an effective ecological approach.

Well done, though it will not matter a row of beans, because those who ARE responsible for the current situation do not react to a reasoned argument.

Sorry about that Rob., but that is the reality. I remind you of the remark by Ian Malcolm, the protagonist in Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park: “In the information society, nobody thinks. We expected to banish paper, but we actually banished thought.”

Our politicians are too clever for words!

On 8 February 1983, some government workers were clearing and burning detritus from a shack on a hill top just south of Orchid Beach. When they allegedly threw aerosol cans onto the fire a wildfire developed. With the aid of Forestry and the Orchid Beach Rural Fire Brigade unit, QNPWS staff utilized the ‘A’ Road from Dunduburra to Awinya Creek track as a defense line. QNPWS staff were dispatched to cut overhanging banksias etc back with chain saws. Back burning took place during the night and next day when I had some heart stopping moments with spot overs, but we held the line. Costs for Forestry and QNPWS were about the same so each covered their own costs. The RFBrigade received some fuel for their involvement.

I understand a settlement was reached ‘out of court’ in response to legal action.

Please note the difference between QNPWS and QPWS.

Ron Turner. Former QNPWS District Ranger

Well done Rob, exactly to the point. My family logged Fraser Island for 55 years until the last log was cut and what is happening is very distressing. It is unbelievable the lack of common sense that has been used with the fighting of this fire. Should never have been allowed to get to this stage. Once logging finished on the Island in Dec 91 my father said it would only be a matter of time till a fire started at one end of the Island and burnt to the other.

David Postan.

Thanks David. Your father was right and foresters also made similar predictions. I think it is a tragedy that the legacy from your family, and other logging families, is quietly being forgotten and erased from historical records on the island. Did you know that a new interpretive shelter at Central Station has 12 new boards – every single one of them about dingoes? Nothing to recognise the contribution of forestry in terms of roads and tracks that the tourists enjoy to get around the island; nothing to acknowledge the infrastructure put in at popular sites such as running water and toilets at Lake McKenzie camp site (no longer allowed to camp there even though an agency set up to manage tourism can’t handle the pressures); nothing about the beauty spots set aside by foresters as examples of the original forests; and nothing about the active management that protected the island from large and destructive wildfires!

Robert, your thoughts succinctly capture and highlight the concerns expressed by Foresters, Fire practitioners, experienced bushmen and practical land managers.

The “lock it and leave-it” approach, coupled with the loss of knowledge and experience of seasoned land managers , the increasing urbanisation of Rural fire fighting agencies (and volunteers unfortunately)the reliance on technology and ineffective & costly aerial fire fighting, has proven to be the recipe for disastrous outcomes. Prevention is more efficient in $ terms and environmental outcomes, however it is not a spectacular political photo opportunity as presented by large aircraft or technologically impressive “Control Centres” ! No inquiry is required. The “Stretton Report ” after the Vic. 1939 fires provided the recommendations that would reduce impacts of not only the FI fire but many of the landscape fires that have occurred since. Forests are dynamic organisms and the failure to manage results in significant changes to structure, bio – diversity and fire occurence and impact. The lack of management on FI extends to the numbers of visitors and the uncontrolled nature of their pursuits.

I have stated before that FI has become a basket case as a result of all of the above.

Well written. I will be sharing this far and wide. Good on you Robert