We have come across sites and stories about war during our travels, primarily associated with World War II. It is true to say I didn’t know much about these events or sites. It certainly opens your eyes to how the war was fought in Australia and how close the Japanese Imperial Army and Airforce got to our shores. The war in Europe began in September 1939, but it wasn‘t until the Japanese advanced into the Pacific in late 1941 that the threat of invasion of Australia was real. Defensive infrastructure was built, particularly along the coast. Following the capture of Singapore on 7 February 1942, military strategists prepared plans to defend the northern and eastern Australian coastline in case of an invasion by the Japanese.

Our first experience of these defence preparations was in the New England Region of New South Wales. We visited wooden tank traps near Tenterfield. Tank traps are obstacles of sufficient width and depth (and in some cases steep sides) at strategic locations to stop military tanks from advancing once they landed on our soil. These traps are part of the concept called ‘The Brisbane Line’. It was a defence proposal formulated in February 1942 to abandon the northern part of the continent if the Japanese invaded and focus defensive efforts south of Brisbane, where most of the population was concentrated. The government didn’t adopt it at the time, but it was a big political issue. The government decided instead to defend the whole of Australia with the recall of soldiers from abroad.

Regardless of the true intent, there is evidence of tank trap locations in various places in Australia. The wooden traps on Mount Lindesay Road near Tenterfield are about one kilometre north of London Bridge, where there was a large army camp during the war with 10,000 soldiers. These traps are located near the top of the Great Dividing Range, designed to obstruct any tanks trying to avoid a roadblock or enemy attack. They are strung between granite boulders and the main road and set up to ‘force up ‘Japanese tanks, exposing their ‘belly’ to Australian fire. It is all very fascinating, but one wonders why position the traps there well away from the coast? Perhaps it was a practice ground for the troops stationed nearby as they trained for overseas deployment rather than an actual tank trap against the Japanese.

When we reached the tropical coast of far north Queensland, we first learned how the military fortified the coastline in preparation for any air or sea attack by the Japanese. When Japanese forces advanced into the Pacific in the dangerous days of 1941 and 1942, coastal cities of north Queensland, such as Cairns and Townsville, were on high alert. Northern ports were critical bases for front line troops. The army set up anti-aircraft gun emplacements at strategic locations. Cairns was transformed from a sleepy sugar cane town to a key Allied supply and training base. Townsville, too, saw its population explode from 30,000 to 100,000. US and Australian forces gathered as the city became a significant resupply and troop transit port. US General Douglas MacArthur brought over troops, guns, and searchlights to combat any Japanese threat.

The Japanese bombing of the US naval base at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941 prompted America and Australia to declare war on Japan. The Pearl Harbour attack showed the Japanese were determined to stop the Allies from using bases in northern Australia. In February and March 1942, they attacked Darwin and Broome with deadly effect.[1]

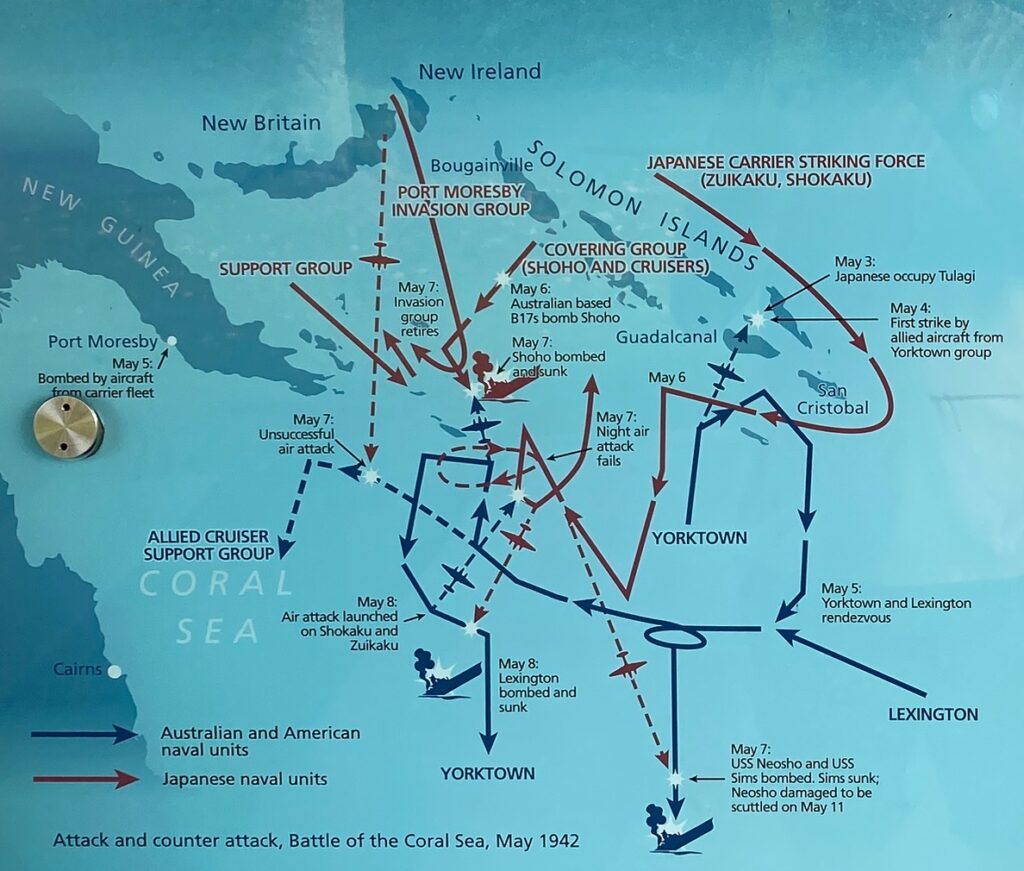

The Battle of the Coral Sea was a pivotal moment for Australia during the war. The air and sea battles between 4 and 8 May 1942 were the largest battles ever fought off Australian shores. It proved to be significant to Australia’s fortunes in WWII. It was also the first battle to be fought entirely by carrier-borne and land-based aircraft. And the opposing fleets did not sight or fire on each other.

The Japanese held Rabaul on the island of New Britain in northern New Guinea and were using it as their principal base in the Pacific. They intended to capture Port Moresby in PNG and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands to isolate Australia and prevent Allied attacks on Japanese forces in the Pacific. Intelligence gathered by the Allies alerted them about Japanese plans. A counterforce was quickly assembled, including the US aircraft carriers Lexington and Yorktown and the Australian cruisers Australia and Hobart. The Japanese attack fleet was made up of aircraft carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. The image below provides the graphic detail of the battle. Although the Japanese sank more tonnage of ships and claimed a tactical victory, their losses in the conflict contributed to the US victory in the Battle of Midway one month later, which was central to turning the tide of battle in the Pacific in Allied favour.

The threat of attack became a reality in late July 1942, with three separate moonlight air attacks over Townsville by long-range and armed ‘Emily’ flying boats from Rabaul. At this time of the war, the Japanese occupied Burma in the west to the Solomon and Marshall Islands in the Pacific. Australian forces were also fighting the Japanese on the Kokoda Track to prevent their advance southwards. For three nights, the sky above Townsville was lit by searchlights and tracers. On the first night attack, two flying boats were caught in searchlights over Townsville and headed back out to sea. They returned an hour later, dropping their bombs in the harbour, missing the wharves. A second raid the next night again dropped bombs which landed in bushland beyond the town. Early the next morning, two US fighter planes duelled with a lone flying boat caught in the searchlights. Only one of its 21 bombs was effective, landing at the racecourse and breaking a few windows in nearby houses.

In 1943 a Fort complex was built by the army on Magnetic Island to act as an important forward observation post for Townsville’s defence. It was one of the most important examples of a wartime coastal defence battery in Queensland. The complex includes fortifications and a camp that housed battery personnel until the end of the war. Army engineers camped on the island in 1942 to survey and clear the main track to transport the equipment and materials to the Fort. Two US-army 155mm guns were sited on the gun emplacements on high ridges, each weighing over 10 tonnes. Two 3,000,000 candlepower searchlights were installed on the island. They were capable of spotting aircraft at 9,144 metres. A radar screen was set in the hill above Orchard Rocks in Radical Bay.

We visited Bribie Island while we were house-sitting at Samford Valley in January this year. I was surprised to find a history of military defences from WWII. With the Japanese attacking further north, military command realised that defence facilities were urgently required for Moreton Bay to protect shipping channels to Brisbane. Large gun emplacements were built at both ends of Bribie Island’s ocean beaches to defend and protect the entry to Brisbane’s port. In the north, two large gun emplacements operated in conjunction with two searchlights and anti-submarine detection loops laid on the seabed between Bribie and Moreton Islands. The signals were linked to remotely operated underwater mines. In the south at Woorim, a fort was built. Two circular guns were also built in the sand dunes, as well as several lookout towers. None of these guns was ever fired in conflict. A consequence of the military presence meant civilians were evacuated off the island during the rest of the war.

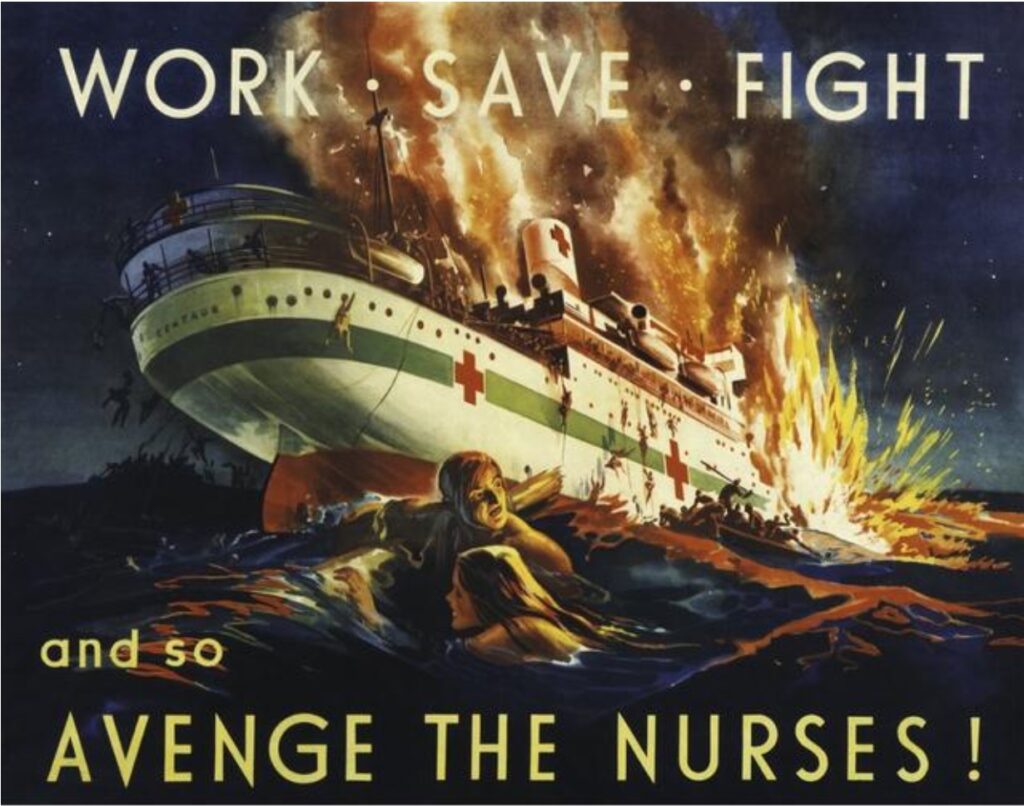

However, an Australian hospital ship, the ‘Centaur’, was sunk in a surprise tornado attack by a Japanese submarine off Cape Moreton in May 1943, resulting in extensive loss of life. This is a remarkable story and not well known in Australia. With the bloody fighting in Papua New Guinea during 1942, ‘Centaur’ was converted from a merchant into a hospital ship in early 1943 to ferry patients between Port Moresby and Townsville. It was attacked on only its third voyage as she steamed from Sydney towards Cairns. A torpedo struck the port side, hitting the oil fuel tank which ignited in a massive explosion. It took three minutes for the ship to sink as it broke in tow after water rushed in the gaping torpedo hole. The survivors were at sea for a day and a half before being rescued. Of the entire crew of 205, only 15 men and one female nurse survived. The attack was on a clearly marked and illuminated hospital ship and reinforced how brutal the enemy was right on our doorstep.[2]

We learnt more war history while in Melbourne earlier this year. At the head of Port Philip Bay, Point Nepean was identified as an important defence location for any invading enemy ships. A Fort was first constructed in 1878, following several war scares in Europe. Armaments comprising 80-pounder muzzle-loading guns in u-shaped gun emplacements were built along with joining underground magazine and tunnel complex. In 1911, the armaments were replaced with longer range 6-inch Mark VII guns. On the day of the formal declaration of WWI, a German steamer attempted to flee Melbourne. A warning shot was fired across the vessel’s bow, stopping the ship. It was interned and the first prisoners of war detained. This incident represents the British Empire’s first shot of WWI. The 6-inch guns remained in service throughout WWII. The first Australian shot of WWII also occurred from Fort Nepean on 4 September 1939 as the freighter ‘Woniora’ attempted to enter Port Philip without stopping to identify itself. After a warning shot, the captain identified his ship and was allowed to continue. Both these incidents are unknown to most Australians.

Did you know about any of these war stories or learn about them at school? I recall learning more about battles in Europe and Gallipoli, Australians success at Kokoda and the Japanese submarines in Sydney Harbour. But I don’t recall learning much about the Pacific war, just how serious the threat of invasion by the Japanese was, and Australia’s defence response.

[1] At least 235 people were killed in the Darwin bombing raid on the morning of 19 February 1942. It was the largest attack by the Japanese against mainland Australia. The bombing resulted in the abandonment of Darwin as a major naval base. The attack on Broome followed on 3 March 1942. Broome had become a significant air base and route of escape for refugees and retreating military personnel, following the Japanese invasion of Java (now part of Indonesia).

[2] When I googled to find out just how many Allied ships were sunk in Australian waters during WWII, I was astonished at the number. A total of 53 merchant ships and three warships were sunk by 54 German and Japanese surface raiders and submarines. Over 1,751 military personnel, sailors and civilians died and a further 88 civilians were killed in air raids. I note the map below does not show where the HMAS Sydney was sunk by a German ship the HSK Kormoran off there coast of Carnarvon, the worst maritime disaster in Australia’s history.

You mention the Woniora during the war when goods were in short supply. There was a popular saying in Tasmania at the time, “its on the Woniora”.

I went to Melbourne in 1942 with my mother on the Niarana and during the night all passengers had to assemble on the deck with their life jackets on for a boat drill as there had been sightings of Japanese submarines in the Bass Strait .

It was pointed out to me by a reader that Victorians claiming the first shot fired by the allies in WWI at Point Nepean is a bit problematic. This is because it most likely happened before the war was officially declared. The war was declared at 11 am GMT, which was about 9 pm Australian time, depending on whether daylight saving was in force then.