Ever since the invention of an electric relay in 1825, the opportunity to communicate long distances in a brief period was provided. When Samuel Morse invented the morse code in 1838, a revolution in communication began – it was akin to the internet in the late 19th century. Around the world, a system of underwater sea cables enabled countries to communicate with each other much quicker. Although Australia had developed telegraph lines on the mainland during the 1850s and a cable linking Tasmania, it remained isolated from the rest of the world. The inability to communicate directly with England hampered trade and business transactions.

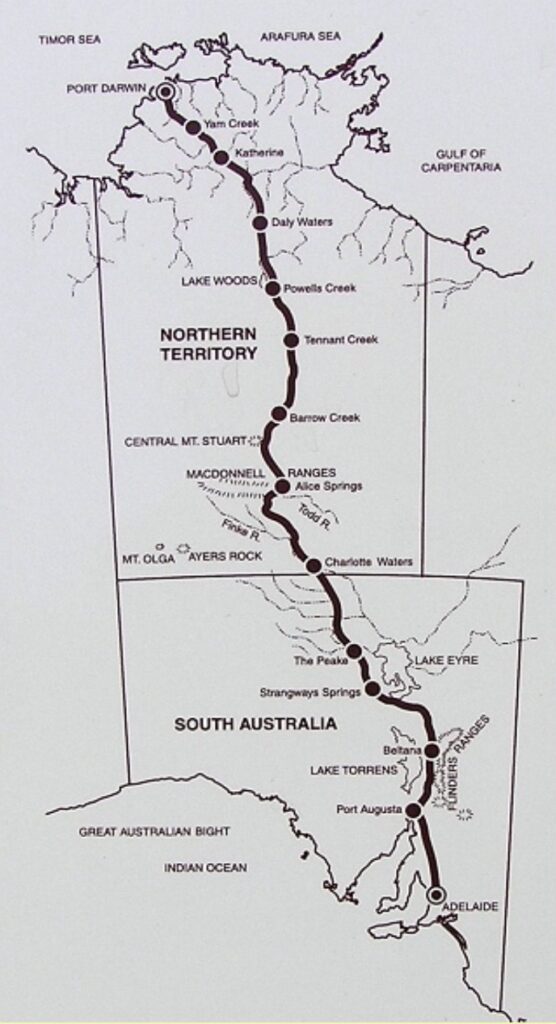

A 3,178-kilometre overland telegraph line, consisting of a single strand of iron wire on 36,000 poles, from Port Augusta to Darwin was built in less than two years. It linked Australia to the undersea cable from Indonesia that came ashore at Port Darwin and made communication between Australia and the rest of the world possible in hours rather than weeks. Mail that had taken 120 days to arrive could now be read within 48 hours.

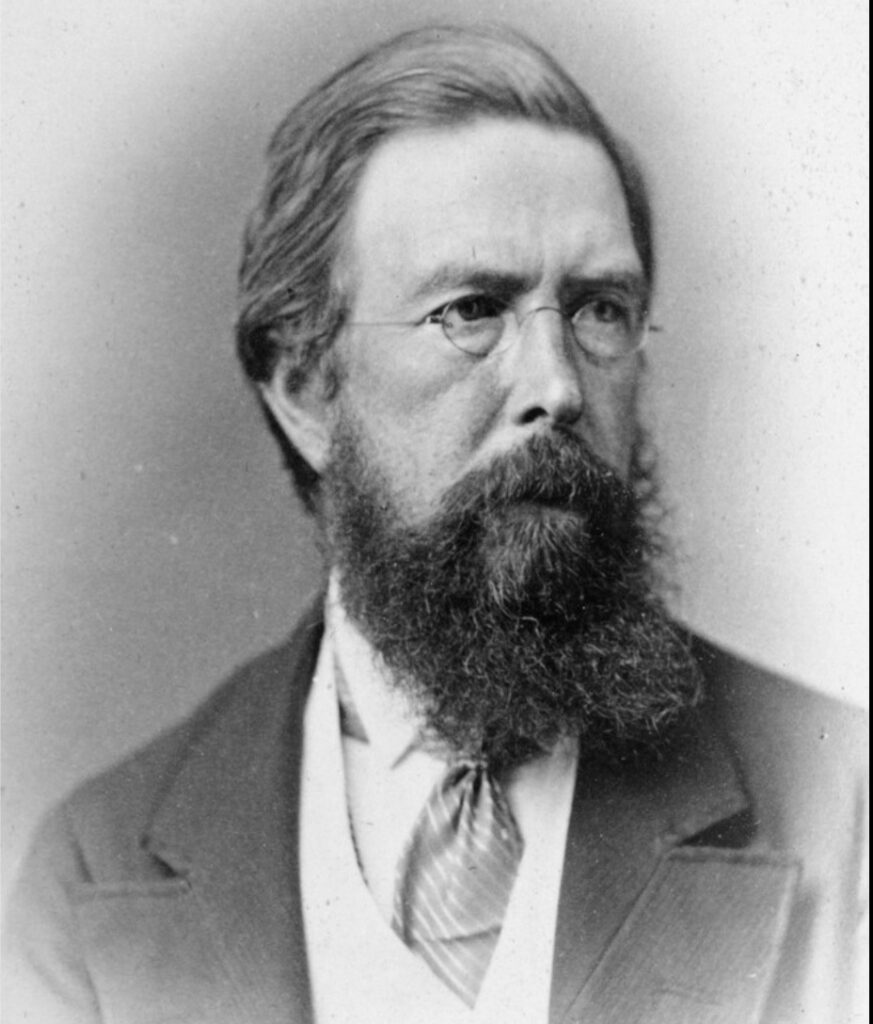

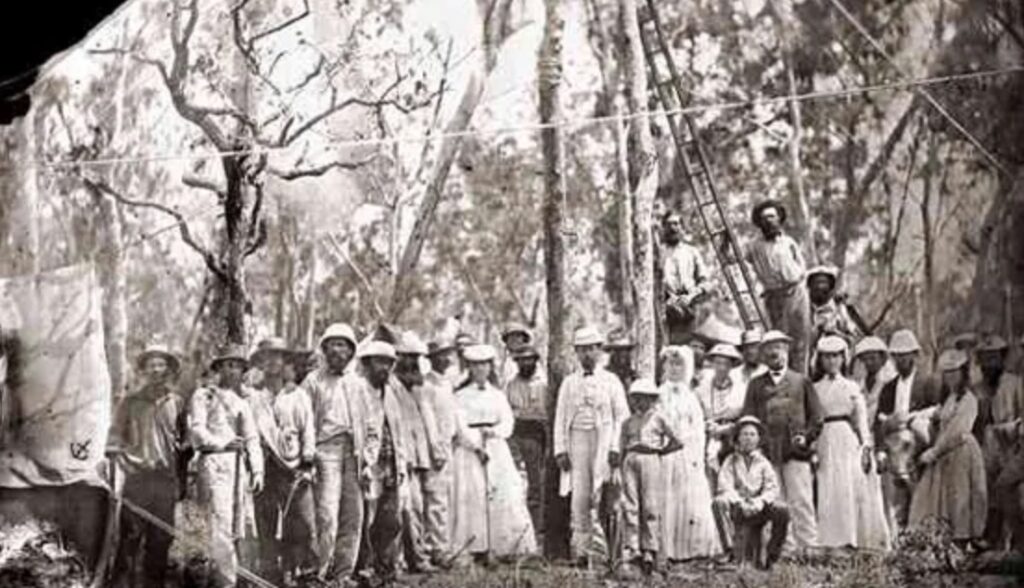

The project was under the direction of Sir Charles Todd, the Superintendent of Posts and Telegraphs in South Australia. It is considered one of Australia’s most extraordinary engineering feats. The line traversed land scarcely explored, and many unexpected obstacles were encountered – cargoes were stranded, supplies ran short, and weevils infested the worker’s flour.

Australia was not a unified country with a central government at that time. Six separate British colonies were all keen to see a sea cable laid to Australia, but they could not agree exactly where it should come ashore and how they would share the costs. In 1858 the South Australian Governor, Sir Richard MacDonnell, proposed landing the cable at Darwin and building an overland telegraph line to Adelaide through the centre of Australia. Todd was unenthusiastic about this idea as he doubted a line could be built across the unexplored centre of the continent.

Enter John McDouall Stuart. He successfully travelled south-north across the continent in 1862, proving that the continent could be crossed. He provided a path for the line from Adelaide north.[1] The South Australian Government succeeded in establishing a settlement at Port Darwin in 1869.[2] It would provide a landing place for the overseas cable and a base to construct the line south. However, there was fierce opposition from Queensland. They wanted the line built across northern Australia through Bourketown in Queensland onto Rockhampton to link with their existing telegraph network. The Western Australians suggested the sea cable land at Perth and the line built along the southern coastline to Port Augusta to connect to the existing telegraph lines.

MacDonnell believed his plan would greatly benefit South Australia, and his plan prevailed when the South Australian government offered to pay the total cost of building the line and complete it by 1 January 1872. It was a huge undertaking. There were no towns along the way, and so everything had to be transported overland. John Ross was assigned the task of marking out the line, which had to have enough water, timber and avoid mountains. He followed Stuart’s track except when crossing the MacDonnell Ranges. The path of the line was divided into three sections to be built simultaneously. The contract was set at building the line over eighteen months. However, the project met with significant obstacles such as drought, flooding, contractor incompetence and the barren country. Still, it was completed in two years – a remarkable achievement.

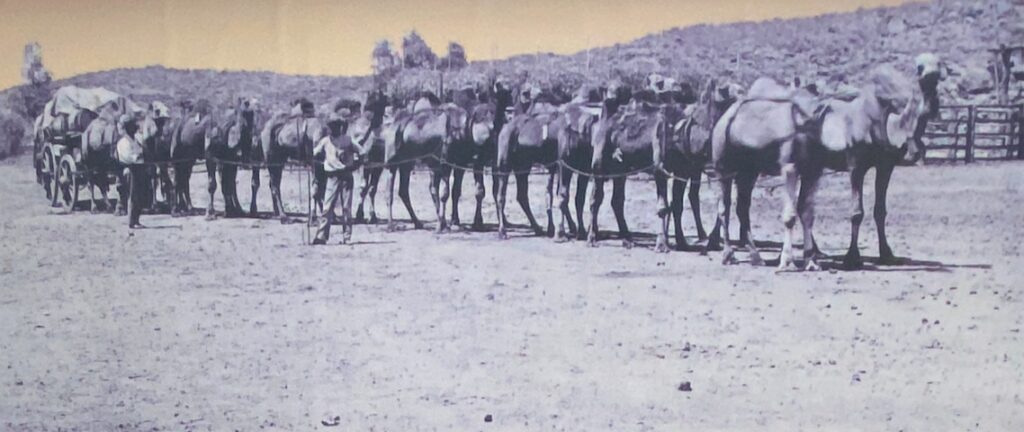

The southern section from Port Augusta to Oodnadatta was relatively straightforward. Much of the area had been explored, and the only real difficulty was finding timber for the poles. Iron poles, wire, insulators, and batteries were unloaded from ships and carted from Port Augusta. A camel holding paddock was at Beltanna, near the Flinders Ranges, which carted supplies north.

Todd thought the central section would be the hardest to build, but the line was erected with few problems. Finding a suitable path through the MacDonnell Ranges proved difficult. Surveyors Gilbert McMinn and William Whitfield Mills eventually found a way through. Mills named a waterhole on the Todd River Alice Springs after Todd’s wife.

Work on the northern section, from Port Darwin to the Roper River, was hampered by the wet season, which arrived only two months after works commenced at Port Darwin in September 1870. Workers suffered in the rain-soaked, boggy soil. They progressed 250 kilometres south to Pine Creek by Christmas but refused to continue in the terrible conditions. McMinn cancelled the contract, and hardly any work was done in the following dry season. Todd sent Robert Patterson to sort out the problems, and after more mishaps and little further progress, another wet season arrived. It was clear the northern section would not be completed on time. Todd took control himself and managed to get the line to progress south with new workers and supplies. The northern and southern ends joined on 22 August 1872. The Overland Telegraph Line cost £239,588, almost double the original budget.

Sending a telegram was still prohibitively expensive with each word costing the equivalent of a day’s wage for a labourer. However, the service was an instant success transmitting over 4,000 telegrams in its first year of service, mainly for business and government.

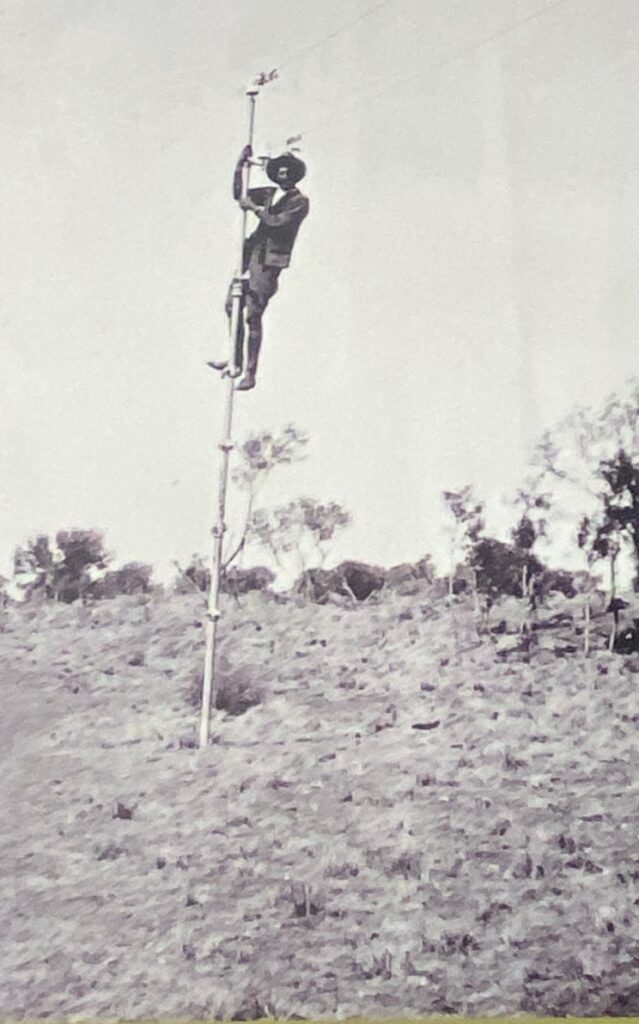

To make the communication system work, on each pole a skirt was placed on the porcelain insulators which kept the top of the wooden pin dry, and prevented ‘earthing’ the line. Despite the design, small amounts of electricity still leaked, making the signal weaker. Maintenance was an ongoing and substantial operation, with Aborigines, floods and bushfires destroying poles and insulators. Plans were made to upgrade the line before it was completed. Cypress pine and river red gum were initially used for the poles. However, most of the wooden poles were replaced with steel Oppenheimer poles from England in 1883.

The overland line became a path for a new frontier. The Post and Telegraph Office in Alice Springs was a vital link for the telegraph line. Every word of world news passed through the Alice Springs station. This was because leakage of current meant a signal would be barely detectable at the end of the line if it wasn’t boosted somewhere along the line. Eleven repeater stations were needed every 250 to 300 kilometres. Telegraph operators and linesman staffed each station. Large banks of batteries were used to power the line. They were in the form of large glass jars holding magnesium and copper sulphate solutions with lead-zinc electrodes. Each battery produced about 1.5 volts. The telegraph system worked by having an operator tap out code on an electric switch called a ‘key’, which sent pulses of electricity from a battery along the telegraph wire. The pulses were either short or long, representing the dots and dashes of Morse code.

Some of the repeater stations grew into small towns. Pastoralists brought cattle and sheep and established stations along the overland line. As the cattle industry grew, the line became part of a network of government stock routes. As underground water was tapped through bores and wells, more people came out to the interior.

The telegraph station near the current Alice Springs became the first European settlement in the region. In 1887, the discovery of gold in the Eastern MacDonnell Ranges brought hundreds of men north along the telegraph line seeking fortune. As the only established settlement in the area, the Alice Springs Telegraph Station and staff could not cope with their needs. In 1888, the South Australian Government gazetted Stuart 3 km south of the telegraph station. Responding to popular demand, Stuart was renamed Alice Springs in 1933.

Over time the telegraph function was replaced by post offices as communication turned to telephones. The overland line continued for many years, and it is believed it provided the news of the Japanese attack on Darwin in February 1942 to the rest of Australia. It is not known exactly when its final use finished.

[1] He made three heroic attempts from south to north in the early 1860s. His principal aim was to find new grazing country for pastoralists.

[2] The territory was annexed to South Australia in 1863 becoming The Northern Territory of South Australia. Responsibility for the territory was transferred to the Commonwealth in 1911 when it became the Northern Territory of Australia.

t’riffic, thanks Robert

Pingback: Ships of the desert – Website | www.robertonfray.com