This blog focuses on two Victorian bush fire disasters 70 years apart. It highlights a failure of governance, a failure to heed fire expert advice, a preoccupation with an emergency response model that has failed in North America and is failing forests and residents in Australia, and an arrogant contempt towards previous bushfire inquiries.

This year, we visited some of the forests affected by the 1939 and 2009 fires in Victoria.

In late February, we enjoyed a walk through the towering mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) forests at Toolangi, not far from the Yarra Valley and on Melbourne’s doorstep. Mountain ash is the tallest hardwood tree in the world. This forest is an enigma because it requires a very hot fire to regenerate but at the same time is killed by those fires.

This particular forest was logged in the early 1930s and wiped out in the 1939 ‘Black Friday’ fires that burnt two million hectares in Victoria alone, razed 1,000 homes and killed 74 people. The townships of Narbethong, Noojee, Woods Point, Bayook West and Hill End were destroyed.

Landowners, graziers, miners and forest workers either deliberately or carelessly lit fires during that summer. They were burning off to clear land and for grass growth. Sawmills located within the forests contributed to the disaster with their careless smouldering fires. Hot, dry and windy conditions occurred In Victoria on Friday 13 January, at the end of a severe drought. All these unmanaged fires coalesced into a mega-fire.

In early April, we stayed in Yea in the Goulburn Valley just north of Melbourne, immediately after the area was swamped by people enjoying an Easter break. We went on a forest drive through Mount Disappointment State Forest. There are visible signs of the catastrophic fire that engulfed the forest 12 years ago on 7 February 2009 – Black Saturday. There were 47 fires on that fateful day that became very severe fires. In just 12 hours, the sky darkened, and carnage was wrought.

As I climbed Mount Disappointment, I was reminded of what happened that day as I witnessed the thick, dense regrowth of mixed eucalypt species overtopped by dead, tall remnant stags.

The Kilmore East fire is the one that swept through Mount Disappointment in February 2009. The fire is not unique in Victoria’s bushfire history – not in its behaviour, weather patterns or forest types that make the area susceptible to severe wildfires. The Royal Commission into the fires on that day considered neither the day, nor the fires, as unprecedented. However, the Kilmore East fire was unique in its devastation – 121 people died, 232 were injured, and 1244 houses were destroyed.

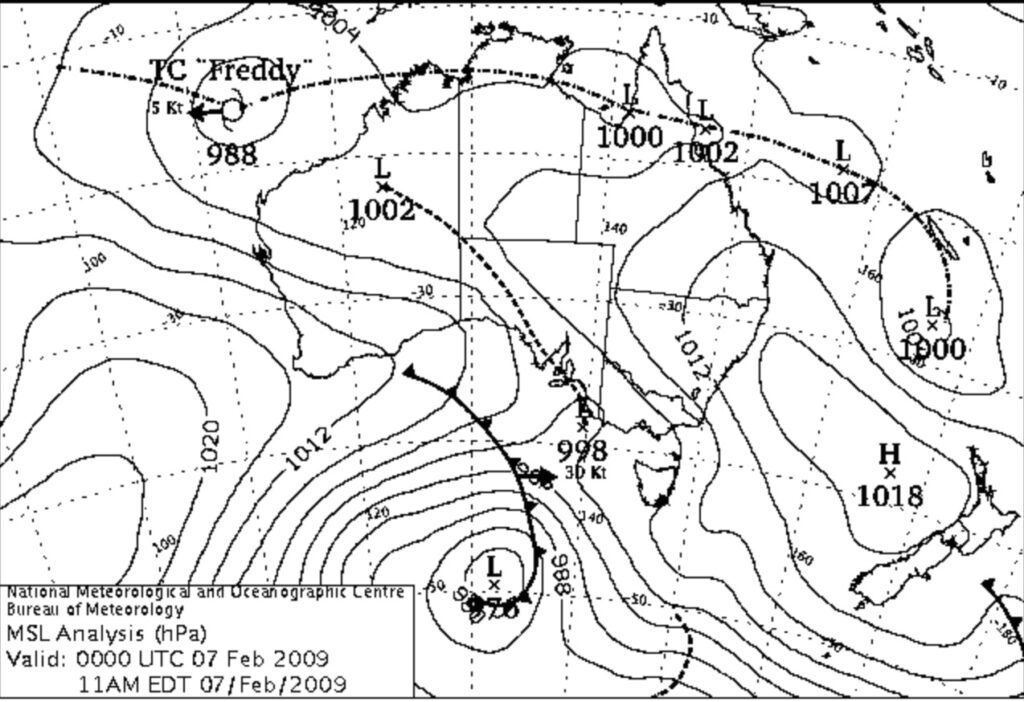

Saturday 7 February 2009 was a hellish day. The early morning forecast predicted strong northerly winds followed by a substantial wind change to the south-west in the afternoon or evening. Since the last week of January, a slow-moving high-pressure system in the Tasman Sea, combined with an active monsoon trough, provided conditions for dry, hot air to be directed over southern parts of the continent. The strong northerly winds on Saturday 7 February brought the hot air to southern Victoria. The worst weather conditions were observed in the afternoon shortly ahead of the wind change. Maximum temperatures were as much as 23 degrees above the February average. Melbourne reached 46.4OC. After the southerly change, wind speeds above 50km/hr continued for some hours. The day was expected to be, and turned out to be, a day of destructive and intense fire weather conditions.

Source http://www.bom.gov.au/vic/sevwx/fire/20090207/20090207_bushfire.shtml

The Kilmore East fire is believed to have started around 11:45 on a rocky hill between two gullies near Saunders Road after an electrical fault in a power line sparked a fire. A northerly wind was gusting at up to 72 kilometres per hour, and the temperature was already at 36.6OC. It initially spread through grassy paddocks and open country in a southerly direction. Various volunteer brigades attended the fire. There was an opportunity to control the fire early if all resources were focused to that end. However, being volunteers with a focus on asset protection of their mates and neighbouring properties, a decision was made by them to protect assets as a priority. Despite incident control knowing about a predicted wind change later in the day, little resources were put on the eastern flank of the fire. After nearly two hours, the weather and the size of the fire combined to make it a much more serious proposition. The fire crossed the Hume Highway at 13:48, with the temperature reaching 42OC. The incident control was in full swing run by the Emergency Services bureaucrats. At this time, the Department of Sustainability and Environment were alerted to the fire. They were surprised there was little advanced planning and strategies to deal with the fire such as proposed forward containment lines. This is an indictment on the current incident management approach. The concern was that if the fire reached forested lands there was nothing that could be done to halt it.

By 15:00, the fire had left the open country and reached the forests surrounding Mount Disappointment, fanned by winds gusting up to 91 kilometres per hour, which had by that time switched to a more north-westerly direction. There were spot fires as far as 40 kilometres ahead of the fire front from embers propelled by the strong winds. The fire spread was measured at 9.2 kilometres per hour with swirling flames over 100 metres high as the fire crowned through the forest. A multitude of spot fires merged into one inferno over 17,000 hectares in just five hours. As they predicted there was nothing firefighting units, firefighters or aerial water bombing craft could do to stop the fire.

The forecast south-westerly wind change arrived at 17:50. It turned the fire’s 55-kilometre eastern flank into the new fire front. The fire had a new destination – small townships in the forested Great Dividing Range such as Strathewen and Kinglake. Before the fire front reached those areas, they were under heavy ember attack. Even though the temperature dropped from 40.1OC to 28.8OC in half an hour, the fire bore down on Strathewen and Kinglake from several directions, running in ‘tongues’, tearing up slopes and gullies through the National Park. The fire quickly doubled in size to over 63,000 hectares as it moved north and north-east, past Kinglake. Fifty-three people died in those two settlements. The fire continued its march towards settlements through the night, reaching Flowerdale about 23:20 where another 11 people died.

Three weeks after the 1939 fires, there was a Royal Commission led by Judge Leonard Stretton. It was a seminal event in Australia’s forest management since European colonisation. He wrote in his report:

“The soft carpet of the forest floor was gone; the bone-dry litter crackled underfoot; dry heat and hot dry winds worked upon a land already dry, to suck from it the last, least drop of moisture. Men who had lived their lives in the bush went their ways in the shadow of dread expectancy. But though they felt the imminence of danger they could not tell that it was to be far greater than they could imagine. They had not lived long enough. The experience of the past could not guide them to an understanding of what might, and did, happen. And so it was that, when millions of acres of the forest were invaded by bushfires which were almost State-wide, there happened, because of great loss of life and property, the most disastrous forest calamity the State of Victoria has known.”[1]

Stretton concluded, “it will appear that no one cause may properly be said to have been the sole cause”. However, the fires were lit “by the hand of man”.

Various government departments competed and bickered among themselves and Stretton wanted “to expose and scotch the foolish enmities which mar the management of the forests by public departments, who, being our servants, have become so much our masters that in some respects they lose sight of our interests in the promotion of their mutual animosities“. The two main bodies in control disagreed on how to manage the forests. The Forests Commission wanted to carry out cool burns to reduce the fuel, despite being woefully under-resourced. The Board of Works felt that controlled burns harmed the water supply, weren’t needed, and wanted to wait for the forest canopy to mature and for the underscrub to naturally thin out in the shade. The problem was that while they waited for that eventuality, big fires would come, destroy the canopy, and let even more scrub regrow in the new light on the forest floor. Stretton was not impressed and commented that by promoting this cycle, the Board ensured its property would “always remain dangerously inflammable…“

Stretton made seven significant recommendations. The first major initiative was the Forests Act 1939, which enabled the Forests Commission to take complete control of fire suppression and prevention on public land in Victoria. He also recommended the protection of forests through a strategic program of burning selected forest areas in a controlled way during spring and autumn.

The recommendations paved the way for the development of a very sophisticated and organised fire management program designed by foresters. It became the envy of the largest and most technologically advanced nation in the world – the USA. Australian foresters focused on managing fuel levels outside of the fire season. They began broadscale landscape prescribed burns under favourable conditions, using aircraft to cover large areas. There was a lot of field experimentation with small fires to provide empirical data to produce field guides for firefighters on fire behaviour and give fire managers a greater understanding of the influences on fire behaviour. Many of these guides are still in use today. Foresters and forestry workers were trained in firefighting and became highly skilled and knowledgeable in the use of fire in the forests. There was a focus on rapidly responding to fires by constructing a network of well-maintained roads and fire trails. Mobile water carriers, fire tankers and heavy machinery were all utilised to fight fires in their early stages and keep them as small as possible. The strategic placement of fire towers allowed for the surveillance of fire outbreaks as soon as they started. This complemented the rapid response capabilities of the Forestry Commission. There was also a full-time workforce with capabilities, confidence and experience in dealing with a range of fire situations. This led to a strong fire culture within forestry.

At the same time, the Americans had already shifted towards a different style of fire management. It increasingly became dominated by aircraft. This response arose because of a need to protect burgeoning suburbs and towns with their assets built adjacent or within flammable forests. The Americans soon realised that while it was a justified response, it failed to reduce the incidence, extent and severity of large wildfires for several reasons. One was a focus on treating the symptoms rather than addressing the factors underpinning the fire risk. The other was the massive expenditure on aircraft reduced the budget available for off-season preventative measures to keep bushfires small.

Sadly, since the 1990s, Australia’s successful fire management system developed by professional foresters has gradually been dismantled and has shifted towards the failed American system with a predominant reliance on huge aircraft to fight fires while ignoring fuel management during the off-season. Environmentalists and city-based academics have successfully convinced governments and the public into believing that broadscale prescribed burns are not an effective management tool, in defiance of experienced land managers and the dictate of Stretton all those years ago. Governments across Australia made sweeping land-use changes to the public estate from actively managed forests nurtured by foresters, to large swathes of forests left to their own devices under what I call benign neglect. The well-trained full-time workforce that could rapidly respond to fires has declined markedly. Governments are more reliant on volunteer firefighters who do not have the same breadth of forest fire experience as foresters and forestry workers. Roads and fire trails have also been closed or not maintained to curtail access within these new parks which stymies a rapid response to wildfire outbreaks.

A new and large bureaucracy has emerged, not to manage fire in the landscape, but to respond to wildfires after they ignite using an emergency response model that centralises control well away from the fire front by bureaucrats with little hands-on fire experience.

The destructive force of bushfires, and how to minimise their impacts, are borne out in major bushfire inquiries since Stretton’s report in 1939. We have a record of 81 years of coronial and parliamentary inquiries. The message from all of them has been similar to Stretton’s inquiry, such as more fuel reduction works, more aggressive attacks of potentially dangerous fires at an early stage, and more use of local knowledge. According to a 1982 parliamentary brief, there is only one factor causing bushfires that land managers can modify to reduce fire risk. That involves using low intensity prescribed burns to reduce the fuel loads. The Commonwealth Inquiry into the 1983 fires recommended that all levels of government have the required systems in place to ensure appropriate fuel management is carried out on all lands under their jurisdiction.[2] The 2009 Victorian Bushfire Royal Commission highlighted the past failings and called on future governments to meet specific area targets for prescribed burning each year.[3] Tragically, all levels of government today, their senior bureaucrats and academic ‘fire experts’ have ignored the recommendations of these inquiries.

Not only have the findings of past inquiries been ignored, the public has become very complacent. Before February 2009, the Kinglake area became a haven for nature-loving people of tree-changers, organic farmers and artists. The local council was committed to deep green policies and the removal of vegetation around houses was repeatedly denied. In nearby St Andrews, where more than 20 people are believed to have died, surviving residents have spoken angrily of ‘greenies’ that prevented them from cutting back trees near their property.

Like many settlements in the region, Kinglake is situated among tall forests of messmate stringybark trees that pose a particular fire hazard, with peeling bark creating firebrands that carry many kilometres ahead of the fire front. Dr Phil Cheney, the former head of the CSIRO’s bushfire research unit and one of the pioneers of prescribed burning in Australia, estimated between 35 and 50 tonnes per hectare of dry fuel waiting to be burnt in February 2009. Fuel loads above eight tonnes per hectare are a fire hazard, and it is known that a fourfold increase in fuel levels leads to a 13-fold increase in the heat generated by a bushfire.

The 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission heard evidence from the late Mr Jerry Williams, a sociologist and historian from the United States Forestry Service (USFS). He explained how the USFS had reviewed its thinking about landscape-scale wildfires. Fire management policy in the US has shifted following a century of trying to keep fires out of forests. The USFS has now identified the need to shift to active land management across all landholdings, taking into consideration land condition and climate, to determine what actions are required for fire prevention and mitigation. It now considers prescribed burning to be an important component of active land management. The Royal Commission final report noted:

“In the past 20 years asset loss and damage and natural resource damage have increased significantly [in the US] despite substantial augmentation of fire protection resources. The increases have occurred in an era in which, as Mr Williams said, ‘we have never enjoyed higher funding levels for fire suppression, greater technology in dealing with fires, better co-operation between government at state and local and federal levels in dealing with these fires.”[4]

In Australia, we are seeing the same pattern expressed above, but governments are only addressing the symptoms and are ignoring the causes. Rather than focus on managing fuels outside of the fire season, there is a total ignorance of fuel build up and a pre-occupation with attacking fires when flames are at the greatest during severe fire weather days. This has lead to a reliance on large air tankers for water bombing, which is a failed management approach, as the Americans can attest. There is now a one dimensional approach to dealing with wildfires that completely ignores the findings from the Stretton Royal Commission in 1939 and subsequent parliamentary inquiries.

Excessive amounts of tax payer funds are being spent on propping up a Bushfire Co-operative Research Centre (BCRC) while fires have worsened. Sixty years of fire research by foresters that developed a very effective fire fighting and fire management system in Australia is completely ignored. These new research centres dismiss landscape fuel reduction burning in their studies and put the blame on other causes such as climate change. They recommend failed fire management strategies which rely heavily on large air tankers to the benefit of so few. Some researchers have even tried to blame timber harvesting as increasing the severity and scale of the 2019-20 bushfires, despite a much reduced area available for logging. Their claims have been comprehensively dismissed by leading bushfire practitioners and researchers but it highlights the narrow-minded focus of bushfire research that is supported by government largesse.[5] The BCRC has a current annual budget of $240 million. It is not unreasonable to question the efficacy of this large spend of tax-payer funds when our wildfire problem and the inadequate response and preparedness continues to worsen across Australia.

Governments have successfully appealed to the urban elite in the inner-city areas who are easily influenced by non-government organisations that spread mistruths about forestry and the environment. These organisations use alarmist language as a tool to raise funds in a competitive industry to pay for influence and the salaries of its executive staff. They quote the ‘scientific’ work of academics closely tied with these organisations and skilfully use the media to promote their work and avoid scientific scrutiny.

Meanwhile, we have governments and the emergency response bureaucracies telling us to be prepared for the fire season while abrogating their own responsibility to manage public forests properly. They allow millions of hectares of public land under their control to become potential fire traps supporting mega-fires with an energy force the equivalent of a nuclear explosion. More and more of these fire disasters occur because the fuels in the forests are not being managed and not because of the oft quoted climate change rhetoric.

In the last 20 years or so, governments have transferred large areas of public land from State Forests to National Parks. Foresters had just managed to develop a successful fire management strategy over nearly 40 years that reduced the number of massive wildfires when governments decided to make sweeping land use changes. The incidence, extent and severity of large wildfires have increased since those changes were made. Is that an acceptable outcome when people’s lives are lost, and millions of hectares of forests are incinerated in one fire event? And why shouldn’t we expect the same disasters to continually occur into the future if nothing changes in the way we prepare for each fire season?

The Victorian government and foresters made changes that were required after Stretton’s scathing assessment in 1939. In 2009, Victoria suffered a similar wildfire disaster, but if you read both Stretton’s and the 2009 Bushfire Royal Commission reports, you will see that the lessons learnt from 70 years are being ignored.[6] When will the government, senior bureaucrats and the BCRC academics be held accountable for this lamentable and avoidable outcome?

[1] https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/CIB/cib0203/03Cib08

[2] The 1982/83 Bushfires: Implications for national cooperation and coordination based on direct State and Territory forest service experience – major conflagrations report.

[3] http://royalcommission.vic.gov.au/Commission-Reports/Final-Report.html

[4] 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Final Report Volume 2: Fire prevention, response and recovery, http://royalcommission.vic.gov.au/Commission-Reports/Final-Report/Volume-2/Chapters/Land-and-Fuel-Management.html

[5] R. J. Keenan, P. Kanowski, P. J. Baker, C. Brack, T. Bartlett & K. Tolhurst (2021): No evidence that timber harvesting increased the scale or severity of the 2019/20 bushfires in south-eastern Australia. Australian Forestry. Published online: 27 Jul 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2021.1953741.

[6] You can read Stretton’s Transcript of evidence and Report of the Royal Commission to inquire into the causes of and measures taken to prevent the bush fires of January, 1939, and to protect life and property and the measures to be taken to prevent bush fires in Victoria and to protect life and property in the event of future bush fires at https://digitised-collections.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/21344

Mate,

You can blog ’till the cows come home but you will change NOTHING! I’ve been at it for 40 years. When you get powerful vested interests involved , bushfires are their way to build empires and get research grants. They actually love them. Without them they get limited money, no promotion and no fancy ‘boys’ toys like water bombers, helicopters and red trucks. Don’t you understand this? Read my piece: ‘Why we burn Again and Again’ and it will lead you through the process.

Hello Robert,

A good summary of the way bushfire management in Victoria has been bastardised to satisfy political and other interests that have no real skin in the game. I share Geoff’s frustration as successive Royal Commissions and inquiries ignore the wealth of knowledge and recommendations from real world experienced land and fire managers. Instead, they adopt the computer generated crap from the activist fire “research” academics who work hand in glove with the epaulette adorned emergency services empire builders.

Given recent inquiries have been led by the clueless (re fundamental fire management issues) and advised by the culpable, it is challenging to find where we can individually or collectively make a difference. However, in NSW, a friend has alerted me to the NSW Audit Office program for this year. So we will be seeing what can be done in this area to highlight the glaring failures and excessive cost of the emergency response model of bushfire mismanagement.

https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/rural-fire-service-preparedness-and-capability