“That lethal cloud rising above Montebello marks the achievement in science and industry in the development of atomic power. [For] good or evil, for peace or war, for progress or destruction. The answer doesn’t lie with Britain alone, but we may have a greater voice in this great decision if we have the strength to defend ourselves and to deter aggression. That was the meaning of Montebello”. Operation Hurricane documentary film of the first British atomic test, Anvil Films for the British Ministry of Supply and Department of Defence, 1953.

The nuclear bombing of Japan in 1945 brought in a new era of warfare. After WWII and the ensuing Cold War between the USA and Russia, Australia got caught up in high-level diplomatic favours. The Americans and Russians raced to develop long-range missiles and atomic weapons. The British and American governments mistrusted the Russians, and the British didn’t want to depend on the Americans for protection. Both countries were keen to develop a nuclear capability to counter what they saw as Soviet Union hegemony.

In 1951, Prime Minister Menzies made a deal with the British government to use Australia as a testing ground for atomic weapons. Top secret activity intensified in 1952 around Onslow in Western Australia as the town became the staging point for Operation Hurricane. Planning was kept secret from the British and Australian public. However, for the townsfolk at Onslow and its surroundings, it was apparent something was happening.

The Royal Navy and a crew of British scientists and weapon designers moved in. With them came ships, crafts and sailors that were not seen in Onslow since WWII. They berthed at the local jetty to take on fuel, water and supplies. The ships were anchored in the bay with small craft running from ship to shore and back. Locals saw boxes of components loaded on and off boats at the town jetty for Operation Hurricane. Catalina and Sunderland flying boats landed, moored and took off in Beadon Bay. They gave a superb display to the locals when landing and taking off in the early morning when the water was calm and looked like glass. The Royal Australian Navy surveyed and chartered the islands and surrounding waters, marked channels, laid buoys and moorings, ferried passengers and supplies and provided a weather ship.

The Army brought in large trucks and equipment. They built roads and provided transport, security and communications. In addition, they erected a tent city on the local sports ground, which became the home for many servicemen during the preparations for the test.

The Royal Australian Airforce used the local town airstrip for military aircraft, including DC3 Dakota’s that flew daily missions.

Apart from supplying the land for the atomic bomb testing, the Bureau of Meteorology provided the Australian contribution – detailed weather information for a year before testing. Forecasting reports were sent from Canberra and detailed information came from the Australian weather ship HMAS Culgoa.

Operation Hurricane was designed to test the effects of a nuclear weapon smuggled into a British harbour onboard a ship. For this purpose, a 25 kiloton plutonium implosion bomb – detonated inside the frigate, HMS Plym, anchored near the Montebello Islands, 100 kilometres off the Pilbara coast – occurred at 8 am on 3 October 1952. The mushroom cloud rose 4.5 km into the sky and left a saucer-shaped crater on the seabed 6 metres deep and 300 metres wide. It was Britain’s first atomic weapon, joining an exclusive club with the USA and Soviet Union as the only nations to test nuclear weapons. It also heralded Britain’s emergence as a nuclear power, and through its collaboration, Australia also entered the atomic age. A press contingent was on hand to witness the explosion, and the little-known coastal settlement of Onslow suddenly became known around the world. The test helped the UK develop the first deployable nuclear weapon called Blue Danube.

The British were not prepared to give any indication as to the time and date of the tests. The contingent of news reporters and photographers were rostered on a 24-hour watch. They slept in their clothes to be ready at an instant’s notice – reporters near their phones, photographers near their cameras. On the morning of the blast, reporters and photographers were at a breakfast function at the local Beadon Hotel. When news came that the bomb had gone off, they rushed through doors and windows to get to their post to photograph and write their stories. Reporters rang the post office, and telegraphists cleared the Morse lines and began transmitting new flashes. The first news of the explosion reached Perth within three minutes. Even the children at the local school turned out to watch the mushroom cloud rise above the horizon. According to a local, well-known publican Cliff Ross hosted a party at his house for the explosion. He interrupted festivities with a message “the atomic cloud has drifting towards Onslow and that people should immediately assemble at the front of the goods shed for evacuation”. It sent many prominent people on a dash of a lifetime, only to realise they had been caught in a prank.

The situation for service personnel on the HMAS Murchison who witnessed the blast was, however, a lot more serious. Official records say the ship was 70 miles away. However, men aboard believe they were much closer to ground zero, as close as 12 to 15 nautical miles and most likely were exposed to radiation from the blast.

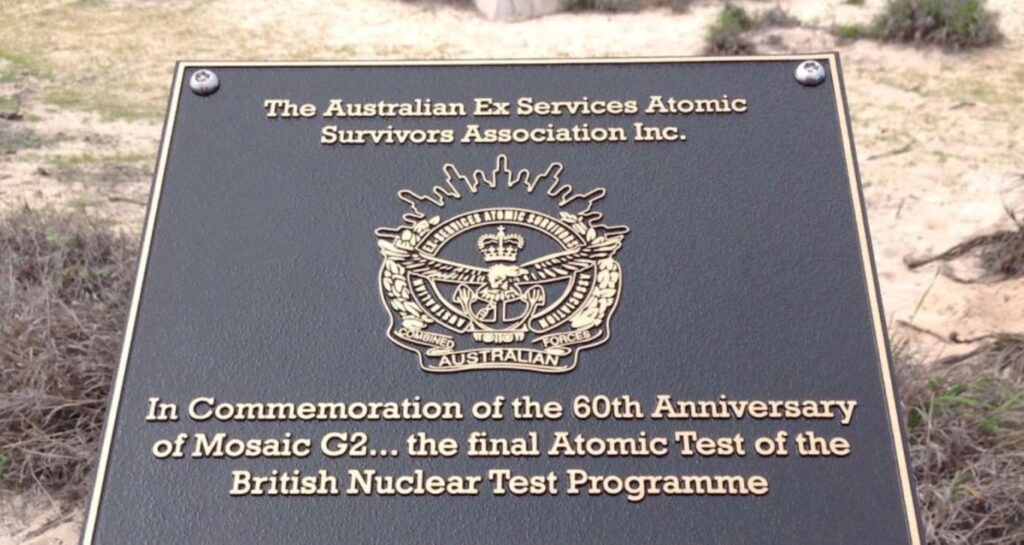

The British revisited in May and June 1956 to explode two more devices under Operation Mosaic. Its purpose was to test the increased yield of British nuclear weapons. It has been argued that the British scientists became more ambitious in their testing by focusing on output and competition with the USA rather than the safety of military personnel. They wanted to use boosted fission weapons, where isotopes of light elements such as lithium-6 and deuterium were added after they heard that using a natural uranium tamper could increase the yield 20 to 50 per cent. While the Australian government prevented the British from using a boosting fusion weapon by experimenting with hydrogen bombs, their testing was closely linked with hydrogen bomb development. The fissile material for the bombs in Operation Mosaic was delivered to Onslow, collected by ship and transported to the Montebello Islands. The bombs yielded between 15-20 kilotons. The bomb cloud rose to 21,000 feet rather than the predicted 14,000. The fallout initially moved out to sea but then reversed direction and headed across northern Australia. Radioactive contamination was found on aircraft at Onslow, indicating that fallout had blown to the mainland.

From 1952 to 1963, Great Britain conducted 22 full-scale nuclear explosions on Australian soil – at the Montebello Islands and in South Australia. During the testing period, roughly 16,000 Australian civilians and servicemen and 22,000 British servicemen were involved in the tests and exposed to the nuclear fallout. However, it is not clear how many civilians, including Aborigines living in remote areas, were affected and, if so, how badly.

A Royal Commission, under Justice James McClelland, into British nuclear tests in Australia was held in 1984 after stories of radiation sickness among atomic test servicemen and local Aboriginal people became known. The Commission concluded that the Montebello Islands were particularly unsafe and inappropriate for nuclear testing, especially with the presence of Aborigines on the mainland near the Montebello Islands. During the 1990s, the Australian government received US$45 million in compensation from the UK to rehabilitate the test sites and to compensate indigenous people. The Australian government presented “a catalogue of official deception and secrecy, cynicism about the effects on the Aboriginal lifestyle and lack of independent Australian control”. The British maintained that the tests were a working example of “generally close, friendly and effective collaboration” between the two countries.

Despite slightly elevated radiation levels still at test sites on Trimouille and Alpha Islands, after nearly 40 years of zero access and 15 years of negotiation, the Federal Primary Industries and Energy Minister, Simon Crean, officially handed over the island group to the Western Australian Environment Minister, Bob Pearce in 1992 at a ceremony staged for the media on one of the Montebello Islands. The only signs of military presence were concrete bunkers, monitoring stations, roads and scrap metal on some islands. The former military operational headquarters can still be seen on the southern end of Hermite Island. The hand-over included an allocation of money to assist in managing the islands, principally to eradicate introduced rats and cats and a series of biological surveys. The Western Australian Department of Conservation and Land Management planned to re-introduce endangered native animals after the feral animals had been removed.

Even after the nuclear fallout of weapons testing and the presence of rats and cats, the islands and surrounding waters support a diverse range of plants and animals. Studies found more than 100 plant, 27 reptile and at least 50 bird species. The shallow waters around the northern islands provided mating areas for green turtles, and the beaches were used by green and hawksbill turtles for nesting during the summer months. This is consistent with what researchers found with wildlife exposed to radiation from the Fukushima nuclear fallout after the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

In 2004, the Montebello Islands were declared a Marine Park after being promoted as “rich in natural marine diversity and human history, and fishers, snorkelers and divers are attracted to its coral reefs, colourful tropical fish, wildlife and maritime heritage”. However, the only way to access them is by boat, with fishing charters operating out of Karratha due to the Island’s isolation.

The history of nuclear testing began on 16 July 1945 when the USA exploded the first atomic bomb under the banner of the Manhattan Project in the desert of New Mexico. Over 2,000 nuclear tests have been carried out worldwide by the Americans, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea in the decades since. The British stopped nuclear testing in 2001, but I am unsure where their testing occurred after Australia. Apart from showing an ability of military might for a short period, I am at a loss as to what tangible benefits arose for the British from their nuclear tests in Australia. For a tiny coastal town in Western Australia, their short stint at world infamy was superseded, many years later, by consequences of exposure to the fallout from the blasts.

At least nature has still flourished on these beautiful and isolated islands.