“The East Kimberley is the land of blacks, Sacks [another prolific local clan thought to be Irish] and bloody Duracks“. Anon

“If one were to paint this country in its true colours, I doubt it would be believed. It would be said at least that the artist exaggerated greatly, for never have I seen such richness and variety of hue as in these ranges and in the vivid flowers of this northern spring.” Stumpy Michael Durack

The early expansion

The frontier port on the Timor Sea, called Palmerston (later changed to Darwin), was noticed after it hosted the northern part of the Overland Telegraph Line. This isolated outpost was the centre for an unexplored and unoccupied land mass of over half a million square miles. The land was one of contrasts – a desert of gibber plains and shimmering salt pans or a paradise of wondrous rivers, rich soil and sweeping pastures. An incredible asset or a hopeless liability. Palmerston began to grow when gold was being mined at Pine Creek and Chinese ‘coolies’ and Manila men were introduced to provide cheap labour on sugar plantations.

In 1870, a tough pioneer drover D’Arcy Uhr pushed a mob of cattle 1,500 miles from Charters Towers to feed the new settlers. But it took another eight years before anyone travelled on that stock route again. In 1876, Sydney and Alfred Prout went north and west from south-west Queensland across the border hoping to stake the first claim on the Barkly Tableland. Unfortunately they both died of thirst. But the quest to run cattle on the large area of pastoral country to feed the Top End was on in earnest. The following year Nat Buchanan, then a partner in Landsborough’s Pastoral Company near Longreach, along with Sam Croaker, rode across the Tableland to the Overland Telegraph. Buchanan followed this up in 1878 to pilot 12,000 cattle from Aramac in Queensland to the Adelaide River, to run on the first Northern Territory station and thus opened a stock route for the big overland cattle drives over the next decade.

An expedition in 1879, led by Alexander Forrest, was the first major and extensive land-based incursion into the Kimberley hinterland by Europeans. Leaving Beagle Bay, they followed the coast to the Fitzroy River and headed inland as far as the Oscar Range. They skirted the King Leopold Range and made it to the Overland Telegraph line near Katherine, just in time to save the expedition party from perishing.

Forrest’s report of the expedition was glowing. He mentioned, “20 million acres of good well-watered country” along the Fitzroy and Ord Rivers. He named the region Kimberley after the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Immediately, over 51 million acres of land were taken up as pastoral leaseholds, sight unseen. A condition of the lease was that the land had to be stocked within two years. The first settlers in the early 1880s initially sought to raise sheep. However, the natural grasses grew up to six feet in the wet season and were of no use for feeding nibbling animals like sheep in the dry.

Most pioneers took up land in the southern Kimberley, and the area north and east of King Leopold Range remained largely unexplored. Meanwhile, the pressure of settlement in the eastern states was steadily creeping north and west. Wheat farms were driving sheep farmers onto traditional cattle country, and cattlemen were keen to find new, remote pastures. They didn’t like the fenced paddocks and the restrictions of closer settlement. They pined for the old days of a semi-nomadic existence on the open range. Only the Northern Territory and Kimberley region offered that opportunity again. A firm of graziers in Victoria, Messrs Osman and Panton, leased land in East Kimberley in 1883. They employed Nat Buchanan to deliver 4,000 head to the Ord River station from Richmond in western Queensland.

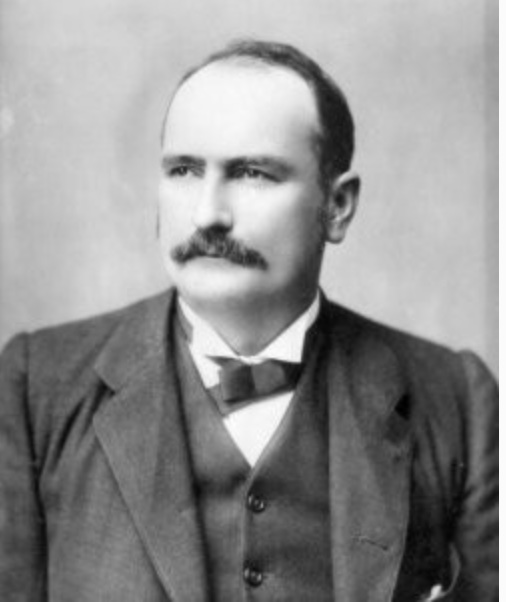

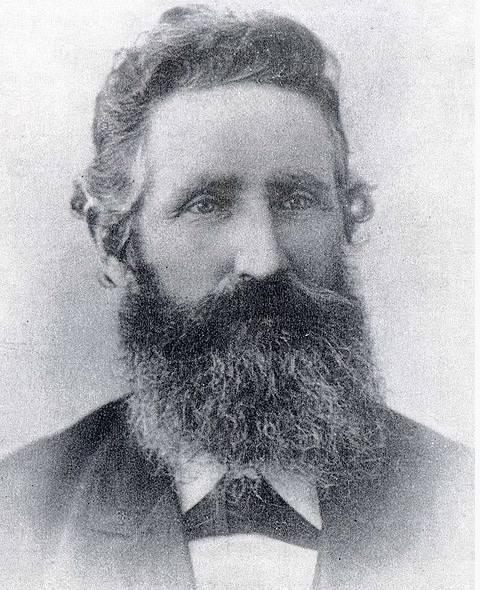

Patrick (Patsy) Durack was the patriarch of a large family of poor Irish tenant farmers who migrated to New South Wales in 1853. He developed land holdings at Goulburn and into south-west Queensland. His passion to explore the vast land and establish large cattle holdings was unrivalled at the time.

Patsy heard about the Kimberley and wanted to evaluate the land before he committed to stocking it. So he planned an expedition that was financed equally with his earlier benefactor, Solomon Emanuel. First he set up a meeting with Alexander Forrest in Perth. Pointing to a map, Forrest told Patsy:

“I can hardly describe the grandeur of that northern scenery – vast open plains heavy with pasture, cut across by creek and rivers, girded by ranges of unbelievable colouring. This Fitzroy country should prove an extremely rich pastoral area, suitable for all kinds of stock, but it its clearly subject to inundation in certain seasons. Farther over here to the east would be, I should say, a cattleman’s paradise with vast plains of splendid pasture, much of it well watered and not subject to flooding since the land is higher and the rivers contained between deep banks”.

Organising the expedition to inspect the Kimberley in the late winter of 1882 got under way in earnest. Arrangements were made to charter three vessels – one to take men, horses and gear from Brisbane to Port Darwin. Then another from there to the Cambridge Gulf and a third to pick them up. The expedition party of eight men was led by Patsy’s brother, Stumpy Michael. Twenty three well-bred horses were purchased from breeders around Brisbane and fifteen hundred weight (about 750 kilograms) of rations and equipment packed. Their motto was to “travel light and ride good horses” and avoid the cumbersome stores of previous expedition parties that required wagons, drays and herds of sheep for killing on the way.

After four gruelling months traversing the country from the Cambridge Gulf, they went home with glowing reports. Under the names of Durack, Emanuel and one or two other interested parties, they reserved eight adjoining 50,000 acres blocks along the banks of the Ord River, 150,000 acres around the Negri Junction, further blocks on the Upper Ord, on the Nicholson Plains and Margaret River, and large chunks on either side of the Fitzroy River. All up covering about two and a half million acres, a comparatively small area to what would become their total holdings in the years to come as part of a vast pastoral empire.

The Emanuels became heirs to the vast flood plains of the Fitzroy and to the spinifex of the desert margins, while the Duracks staked their fortune on the rolling basalt downs and rugged quartzite ranges along the Ord.

The Duracks organised their expedition to the Kimberley holdings from their base in Queensland called Thylungera, on Coopers Creek. The expedition was larger than Buchanan’s, had to travel further and began in worse country. Four mobs of 8,000 cattle, horses, wagons, and supplies left on the 2,500-mile journey. These were tough and hardened characters who straggled across the country with their herds. First, they faced drought in Queensland and then monsoonal rains and crocodile attacks on the cattle. Often, they were held up for weeks, enduring fever and disease. The journey took two and a half years to reach the Ord River in 1885. Along the way, half the cattle, many horses and a few men died.

Each of these overland trips by Buchanan and the Duracks was a saga of heroism and persistence. And with them started the legends and the mythology of the north that has moulded the characters of today.

Joseph Bradshaw, who took up lots of land around the Prince Regent River, led a small expedition party out of Wyndham in 1891 north and west along the Prince Regent River. However, he ended up further north than planned. He noted some unusual rock art forms and age differences from the figures previously described by George Grey. The enigmatic figures depicted on the rock walls were known for many years as the Bradshaw paintings. Bradshaw’s expedition led to more pastoralist interest with further exploration.

Other mobs followed, and by 1917, there were over 600,000 cattle in the East Kimberley and a port established at Wyndham. The question of access to markets for stock, however, became a priority. Patsy’s eldest son was Michael Patrick. At a young age, he was sent to the family’s head station, Argyle Downs, in 1886, just in time for the Halls Creek gold rush. He made the first sale of Kimberley cattle to a Halls Creek butcher, and payment was in gold. Michael found new markets after the Halls Creek goldfield declined by overlanding stock to Pine Creek and Derby.

Francis Connor and Dennis Doherty were two young Irishmen who were attracted to the Kimberley from Sydney by the gold rush. They set up a merchant and general business in Wyndham and acquired a pastoral lease adjoining the Durack’s which they named Newry after their mutual birthplace in Ireland. They subsequently started a shipping trade from Wyndham to Perth in 1894 when the local pastoralists found it difficult to sell their cattle to the local market following the gradual drifting of alluvial miners from Halls Creek. The Duracks became the leading supplier. In 1897, a new pastoral company called Connor, Doherty and Durack Ltd was formed. Between them, they controlled properties totalling nearly 6,000 square miles on the Western Australia and Northern Territory border and dominated the export trade out of Wyndham. The aggregation included Argyle, Ivanhoe, Auvergne and Newry stations.

Wyndham town

Wyndham was spawned in the 1880s with the Hall’s Creek goldrush, but it refused to grow up in the right place. Government surveyors prepared a townsite three miles from the original wharf, but the diggers camped where their stores were dumped, and the settlement grew up around them. It was the location of the only deep-water port on a long stretch of coastline. And it became the centre of rich cattle country in East Kimberley. However, it was unable to expand due to tidal mudflats located at both ends of the main street. For this reason, in 1968, the town was “moved” to Wyndham 3-Mile, and the old town was renamed “Wyndham Port”.

It is the most northerly town in Western Australia and the hottest by nearly ten degrees. Located near bare-baked saltpans that turn into a pressure cooker by the surrounding high red-rock hills, Wyndham is hot. The average maximum daily temperature is 36OC.

Pastoralists originally sent cattle from the East Kimberley stations overland to Derby. But with the construction of Anthons Landing in 1894 in Wyndham, the East Kimberley cattle industry officially began. Cattle were shipped to Robb’s Jetty Abbatoir at Fremantle, Arab states and Philippines Batavia (Indonesia).

Over the following decade, the growing pastoral industry, led by the Durack family, prospered. However, moving cattle to Wyndham and then by ship to ports was a costly exercise. First, they had to be shipped, then fattened and conditioned after landing. As a result, pressure mounted on the government to build a meatworks at the Wyndham Port to allow Kimberley cattle to be processed in the town.

How Wyndham got a meatworks

In 1890 there were slaughter houses in Perth at Robb’s Jetty to supply the meat for the metropolitan area and the expanding goldfields. Extensive allotments were set aside for pasturing the animals in areas surrounding the abattoir. However, they had no cold storage. Lord Vesty was already developing chilled and frozen beef products in Queensland with refrigeration ships. It was a new concept to the domestic market but vital in creating an international market. Household refrigeration was patented in 1891.

In the 1890s, the population of Perth and the goldfields grew, which led to widespread food shortages in Western Australia. Most of Western Australia’s beef came from the Kimberley. However, cattle from East Kimberley were quarantined at that time due to an infestation of tropical ticks. This fuelled high prices for meat driven by the West Kimberley pastoralists, who dominated the production and shipping of cattle. Dubbed the “meat ring”, the Labor government feared private development that would favour the West Kimberley pastoralists. A Royal Commission was called in 1904 to investigate the activities of the West Kimberley “meat ring”, which allegedly controlled the price of beef. The Commission recommended a canning and beef extract plant at Wyndham. James Isdell, an independent member for the Pilbara, proposed the creation of a stock route through the desert to transport East Kimberley cattle to the goldfields. He argued, accurately, that the ticks would fall off and die in the desert climate. It became known as the Canning Stock Route after its surveyor Alfred Canning.

In 1907 the Liberal government offered a £35,000 subsidy to investors willing to establish a meatworks in Wyndham. At the same time, Bovril Australian Estates proposed to operate a shipboard canning and beef extract process plant in the Cambridge Gulf, but this was rejected. Instead, the company announced it would build in the Northern Territory, and this led to a debate over the potential of Wyndham versus Darwin and the Wyndham proposal lapsed.

In 1912, the Labor government purchased three steamships to lower the “unbridled monopoly of the two private shipping cartels” running out of the north. A crippling drought in 1913-14 led to rising unemployment and loss of stock shipped live to Fremantle. To alleviate these problems in the future, the government decided to build a meatworks in Wyndham. The meatworks was completed in 1918, and cattle processing began a year later. Most of the beef and by-products were exported. Britain was the primary market due to the “Empire preference” tariff policy. Around this time, an L-shaped jetty was built to service the new freezing works.

Stock for the meatworks was walked from cattle stations in the East Kimberley via a range of stock routes. Northern Territory and Ord River to the east, Bedford, Halls Creek and Kurunjie to the south. It could take over a week to travel with a supply wagon to Wyndham, but they were vital links for the outlying stations to the port at Wyndham. The government set up the “Beef Roads” program in 1949 to provide funding for the infrastructure to support the beef industry. The Gibb River Road was constructed as part of this program – a three-year road-building project. It only partially followed the old Karunjie Track and Mount House Road and went west to Derby. With the benefit of explosives and heavy machinery, a new direct route was built through the Napier and King Leopold Ranges. The eastern section was completed in 1967.

During 1921, the meatworks was forced to close due to low prices and renovations. It also closed during WWII. After 48 years, the government sold the meatworks to a private company in 1967. It suffered extensive damage in a severe fire in 1972. By 1985, the meatworks struggled and operated on a shorter season due to a slump in the pastoral industry. The killing of buffalo helped keep the meatworks running. However, the plant finally closed in 1986.

Hard times and irrigation

During the 1920s, cattle prices were poor, and the stations struggled. The Depression followed, and the Connor, Doherty and Durack properties were heavily in debt. The cattle industry in the Kimberley was hardly surviving. Michael’s eldest son, Reg, spent one long wet season and most of the following year mustering wild cattle from the most inaccessible places to drive to other properties and de-stock the outstations.

Michael tried to negotiate an aborted attempt to form a Jewish homeland on their properties for refugees from Nazi Germany. After WWII, while the more isolated runs came under development, especially in the Leopold country, parts of the East Kimberley were known as the “slum area of the Kimberley”, not only because of dilapidated old homesteads but because they included the worst-eroded and most under-improved land under settlement.

Kim Durack, the fourth child of Michael, believed changes were needed to manage their properties after fifty years of open-range grazing. He brought in the first plough to the East Kimberley region and advocated the introduction of irrigation for pasture management, complemented by crops. He experimented with lucerne at Argyle before establishing an experimental plot at Ivanhoe on the Ord River. Between 1942 and 1945, Kim and his brother William successfully grew trials of sorghum and millet, and they played a part in establishing an experimental research station at Carlton Reach on the Ord River. Kim was also instrumental in lobbying for and selecting the site for the Ord River dam.

A dam proposal had been bandied around for quite a while. The fertile black soil plains of the Ord River were believed to be suitable for tropical crops. However, the formidable wet season flow of the river was reduced to a series of waterholes each dry season and technology to harness the waters was not yet available.

In 1947, Kim Durack instigated a proposal to form the Kimberley Development Council to decentralise administration of the district, make land use more efficient, improve living standards, reduce dependence on southern products and establish local industries for consumption. The Council would advise the State government in all matters affecting development policy for the Kimberley region. Eight hundred signatures supported his proposal, and it went to the Lieutenant Governor, Sir James Mitchell. Instead, Mitchell set up a semi-official Kimberley Regional Advisory Committee to consult on matters affecting the Kimberley and the north-west area in general which delayed any meaningful progress in the area.

During the post-war period, there were more than 350 European men permanently employed on stations in the whole of the Kimberley region, including owner-managers. In addition, most stations maintained their own “black camps” from which they drew their supply of stockmen and “house gins”. Because of the under supply of stockmen, open range grazing gave way to paddocking with artificial water points.

During 1949 and 1950, several long-term interests sold out to a new wave of owners. William Buckland bought Rosewood. Tom Quilty transferred his interests in the Northern Territory to reinvest in the East Kimberley, purchasing Springvale, Lansdowne and the Six Mile Hotel in Wyndham. He already owned Bedford Downs and the outstation Arizona.

Finally, the Peel River Estates of New South Wales bought Auvergne, Argyle, Newry and Dunham River from Michael Durack, which hampered his son Kim’s ambitions to develop an irrigation economy.

At that time, Michael was alone after his brothers and business partners’ deaths, so he decided to sell the Durack stations, maintaining that he “would rather bequeath a lump of money to his heirs than a lump of land with its problems attached”. Sadly, he died not long after the sale of the properties. These transactions confirmed the hold of the great capitalists on the East Kimberley pastoral industry. Of the 231/2 million acres held under lease in 1950, nearly 40 per cent were held by 24 resident owners.

With the sale of the properties and the death of Michael, the pioneering legacy of the Durack family in the region came to an abrupt end, despite the efforts of Kim to diversify the family business interests and keep their holdings profitable. What followed was a cruel twist of fate to further reinforce their downfall and disappearance from the area.

The Ord River Project goes ahead

After many years of agricultural studies and engineering assessments, a grant from the Commonwealth government in 1959 enabled the Ord River project to commence the following year. A new town to service the project was gazetted and called Kununurra. The first step was to construct the Ord River diversion dam, holding back what became Lake Kununurra. It would harness and raise the water level high enough to enable gravity to do the work of transporting water for irrigation onto the Ivanhoe Plain north of Kununurra. In addition, it stores 758 billion litres of water for 21,000 hectares of agricultural land for horticulture, cropping, forestry and grazing.

Next, the works for the Ord River dam started in 1969 and was completed three years later. As water backed up behind the dam wall, it created Australia’s largest artificial lake, Lake Argyle. With the addition of this water, over 73,000 hectares of land could be irrigated, including Packsaddle Plain south of Kununurra.

Unfortunately, the water rose quicker than expected, flooding the pastoral plains of the ex-Durack held Argyle station. Well-known naturalist, Harry Butler, led Operation Noah to rescue as many stranded animals as possible. At the same time, the homestead was under threat of going underwater. As a result, the main house was dismantled, stone by stone and moved to storage in Kununurra. Grants from the federal and state governments enabled the reconstruction of the homestead house, and it was opened as the Argyle Homestead Museum at its present site above Lake Argyle.

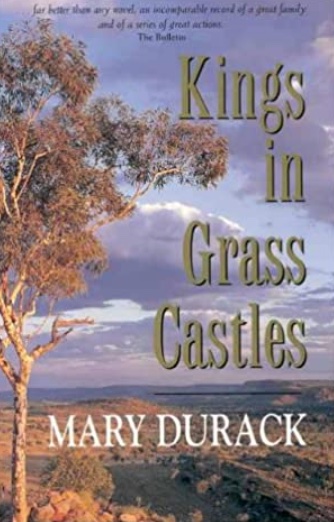

Michael’s second child, daughter Mary Gertrude Durack, had a flair for poetry and creative writing at a young age. Over many years she penned articles for newspapers, wrote books, some with her younger sister Elizabeth. We are very fortunate that the Durack family possessed someone with a literary background who could combine her skills as an imaginative storyteller with detailed family archival research. Her family history published in 1959, “Kings in Grass Castles”, stamped her as an accomplished writer. The book relates the history of her ancestors’ departure from Ireland, their establishment at Goulburn, New South Wales, and migration, first to western Queensland and then onto the Kimberley.

After her father’s death, Mary went to the Ord River dam site. She watched the Ord River dam slowly inundate the former family stations (a million wild acres of rich pastoral land) out of existence.

This was when she decided to draw upon the wealth of family records, kept at her father’s office in Perth, to write a sequel to her first family history, called “Sons in the Saddle”. It is well worth reading both her beautifully written books to appreciate the triumphs and tragedies that the well-known Durack family experienced, the pioneers of the rugged and isolated East Kimberley region.

I leave the last words to Mary Durack who wrote in a “letter of the future” about the diaries, letters and papers she inherited after her father’s death:

“Should I never have the opportunity of getting down to it I am writing this to give some idea of what is to be found in the files and documents kept…so that the whole remarkable and in a sense tragic story might be translated into some meaning and significance to ourselves and our country“.

I think I speak on behalf of all Australians when I say we are truly thankful that she did eventually publish works from these documents.

I spent a year working in the East Kimberley in 1981 before attending university at ANU. Firstly, mustering wild cattle on horseback on Bradshaw Station then later as part of a feral bull catching team on Auvergne and Newry Stations.

All the cattle were transported to Kununurra or Wyndham and the name Durack was synonymous with the area even then.

I caught catfish on the shores of a young Lake Argyle and wondered at rock paintings in hidden caves likely unvisited since.

The landscape is unforgettably magnificent, the remoteness and climate surreptitiously hostile. It is no place for the capricious and, for the uninitiated and unwary it can prove lethal.

From it’s first inhabitants I discovered the land provided an abundance of wealth. Goanna, flying fox, bush turkey, wallaby and water snake. All are good to eat when seared over hot coals on a quickly assembled fire. The early Europeans, however, would undoubtably have struggled to survive in such a foreign place.

When I was there I remember seeing pink tape and survey pegs in remote places and there were rumours of diamonds in those ruby coloured rock faces.

My memories of the East Kimberley are indelibly imprinted within my imagination. I miss that place still today.

So interesting Robert, happening not all that long ago!

Thankyou.

Robert, why didn’t I read this potted history before we went to the Kimberley last year, soon after meeting you. You reminded me I have Grass Castles waiting to be read.

Next week we are off to Tasmania to play bridge and I shall do my Surrey Hills reading before we go.

Thank you.

Geoff