In Chapter 6 of my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, I alluded to the acrimonious relationship between James Norton Smith, the Chief Agent for the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.) and William Ritchie, the Chairman of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company (MBTM Co.).

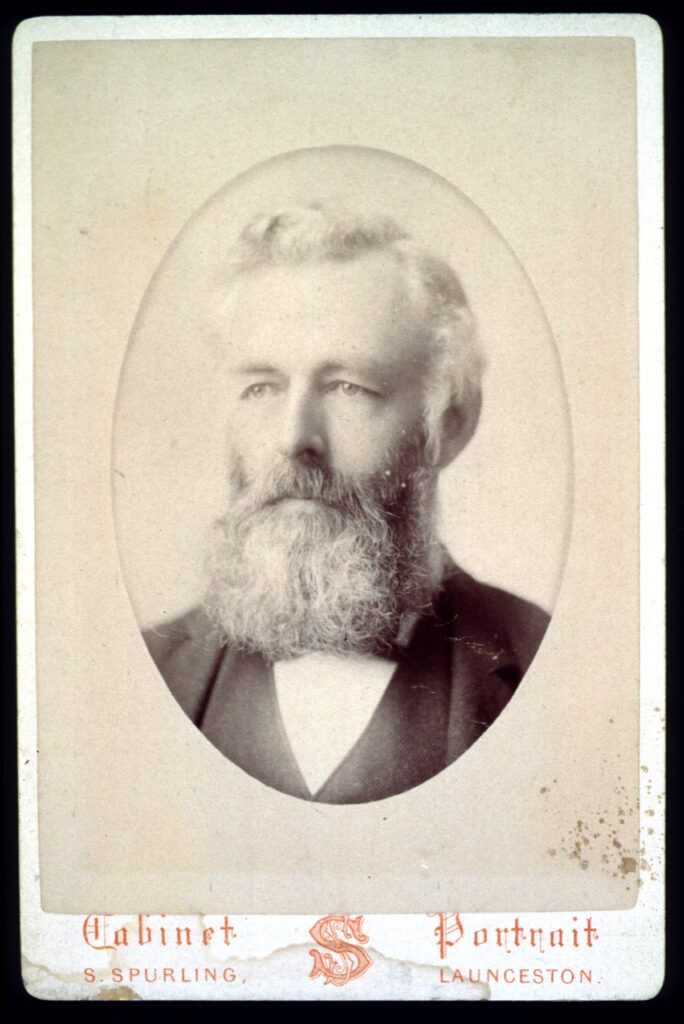

In early 1881, the animosity spread to a public spat, which is fascinating, not least because Ritchie was a partner in the law firm that acted as the VDL Co’s solicitor for their Tasmanian dealings. Their feud was over several issues. However, it focussed mainly on the freight charges to cart tin ore over the VDL Co’s tramway.

The VDL Co. owned all the land between their mine and the port at Emu Bay (except for the last three miles). The MBTM Co. believed that gave them a monopoly over the movement of ore and goods to and from the mine.

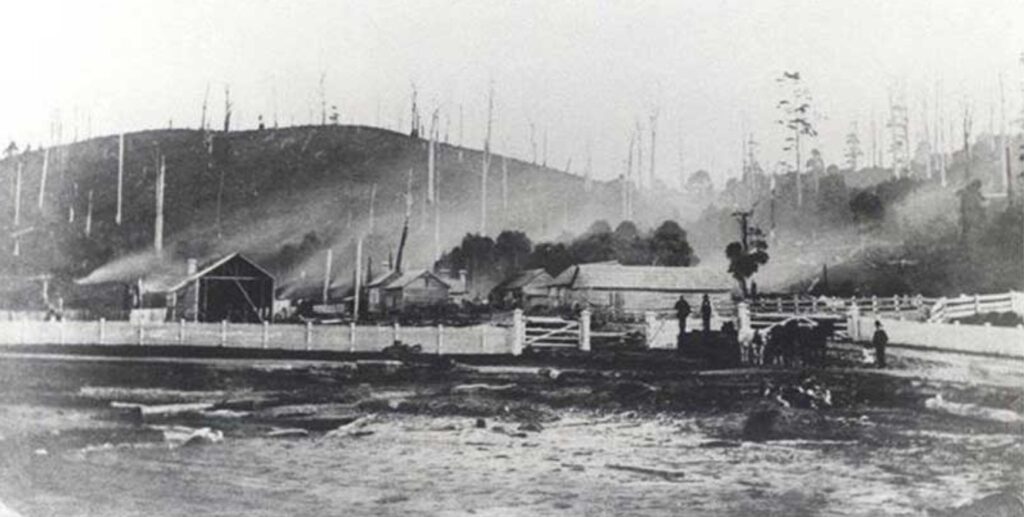

The government considered funding and building a new road to Mt Bischoff from the coast near Table Cape and Wynyard after numerous petitions and representations from vested interests at other ports along the north-west coast, including the MBTM Co. That proposal would have taken freight away from the VDL Co’s port at Emu Bay. The VDL Co. didn’t want that and decided to construct a wooden horse-drawn tramway because the original dray road, built by the VDL Co. in the late 1820s and never maintained, could not sustain traffic all year round.

The VDL Co. were happy to see the tin mine flourish at Mount Bischoff to improve their own business and profits.

While the initial costs for a tramway were estimated to be reasonable, the VDL Co. were reluctant to expend their own funds to build the tramway. They offered to give the necessary land to a company to construct the tramway instead, but none took up the offer. Furthermore, they dismissed building a more reliable railway because of the high cost.

The VDL Co. ended up building the tramway with its funds and faced a cost blowout from the original estimate of £250 per mile to nearly £1,100 per mile. It put considerable strain on the company’s funds, and it had to resort to capital raising from shareholders and a mortgage over its lands.

The VDL Co. completed the tramway in February 1878. A contract between the two companies set the cartage rate at £4 per ton for the first three years. However, the MBTM Co. had always thought that if the government had built a fully macadamised road instead, the cartage rate would have been lower at £3 per ton.

The directors of the MBTM Co. wrote to Norton Smith in March 1880 seeking to reduce tin ore freight charges. Norton Smith believed their request was unreasonable. He wrote to the VDL Co. Court of Directors outlining that the MBTM Co. proposed to call tenders to cart their ore the following summer. Norton Smith believed that the VDL Co. held the upper hand as it planned to extend their tramway from Rouse’s Camp at the western boundary of Surrey Hills to Waratah. It would give the VDL Co. an immense advantage over other carriers because they could transport ore from Waratah, and the MBTM Co. would cease to operate its tram between Rouse’s Camp and Waratah.

Norton Smith believed that while the MBTM Co. could transport their ore and goods by drays more cheaply during the summer months, they would be obliged to use the tramway during the extended winter period. So he planned to offer £4 a ton for all goods all year, or £2-15s per ton between November and April, and £5-5s per ton in the remaining months. He was confident no other carrier could compete with these prices, and they would carry sufficient ore at the higher rate to make sure the deal was profitable for the VDL Co. However, his proposal was rejected by the Court of Directors as they feared the lower summer rate might encourage a concerted effort by the MBTM Co. to reduce the current rate.

Ritchie’s brother Henry, the manager of the MBTM Co. mine, wrote to Norton Smith in September 1880 again seeking a rate reduction for freight. He argued that the MBTM Co. was entitled to a considerable decrease because the £4 per ton rate was based on delivering 2,000 tons of tin per annum. According to Henry, the VDL Co. promised to reduce the rate if traffic increased beyond that quantity. The tramway was carrying over 4,000 tons per annum. In the margin of that letter, Norton Smith noted “no such promises made” and refused to entertain a reduction in rates in his reply to Henry.

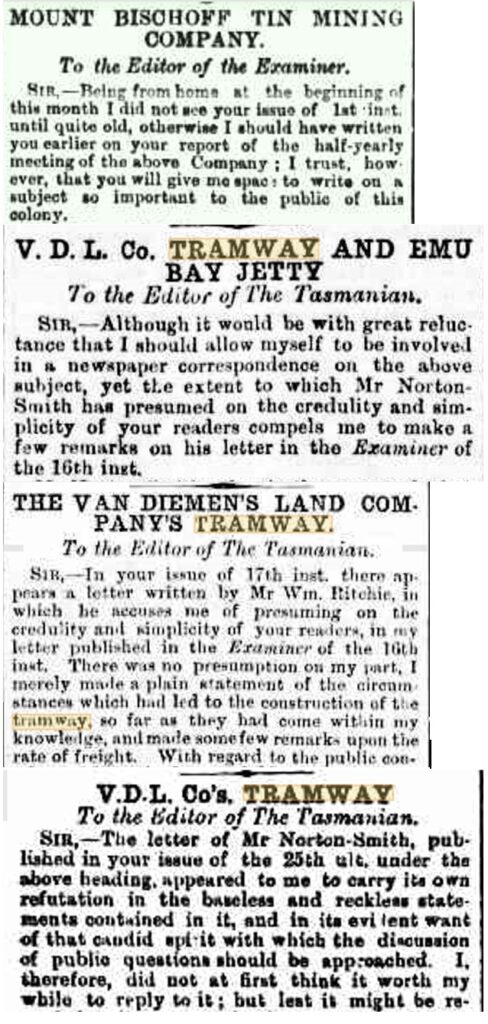

By the end of 1880, when the original cartage contract expired, the angst between both companies hit a new level. The newspapers reported the half-yearly meeting of the MBTM Co in February 1881, which included comments made by the Chairman, William Ritchie, about the freight rates. The antagonism took off and shifted from private correspondence to the public sphere through an exchange of letters in the newspapers between the protagonists in February and March 1881. The letters were lengthy tomes, with neither giving ground to the other.

Ritchie argued strongly that the cost to freight everything from essential everyday items, passengers and tin ore on the tramway was excessive. In some ways, his argument was that the VDL Co. had a duty to subsidise the costs of moving things to the isolated outpost because they had a monopoly on the carriageway.

However, Ritchie failed to appreciate the high running and maintenance costs of a second-class wooden tramway over such a large distance. The VDL Co. faced constant maintenance pressures and wages and feed costs for the horses that continued to increase each year. But that was the least of Ritchie’s concerns. He believed that the original deal signed with the original owner of the mine, James “Philosopher” Smith, was too advantageous to the VDL Co.

Ritchie wanted a much better deal once that initial agreement expired. And while he expressed a reluctance to engage in a public argument, he wrote his letters to garnish public sympathy in his favour. For example, Ritchie bemoaned the lack of opportunity to use the alternative dray road to compete with the VDL Co. However, he failed to admit that the MBTM Co. had been forced to pay rates as high as £10 per ton on the dray road before the tramway was completed.

A study of the financial position of both companies at the time helps provide some background perspective to the arguments over freight rates. The VDL Co. consistently struggled to make enough profits to pay dividends to its shareholders. During the mid-1850s, after they ceased farming operations, the directors seriously considered winding up the company.

Once the tramway was completed, the VDL Co. had a regular revenue stream and made modest dividend payouts for the first time in twelve years. In its 1880 report, the VDL Co. had £890 in its bank account after a dividend distribution of £5,400. In comparison, the MBTM Co., in only its eighth year of operation, reported a bank balance of over £30,000 after paying out £36,000 in dividends to its shareholders. The MBTM Co. directors believed that the “splendid dividends hitherto paid will be maintained and that a long career of prosperity is before the company”.

And so it was, with the company on the start of an ascendancy that saw original shareholders earn returns over tenfold on their initial investment. In March 1882, it was reported that the MBTM Co. paid out £276,000 in dividends or £23 per share, which initially cost investors £5.

Norton Smith penned the first letter in the newspaper taking a pot shot at Ritchie by highlighting the “philanthropic” motives of the VDL Co. in building the tramway in contrast to the motives of the directors of the MBTM Co. The latter were more motivated by wealth generation. But it was apparent Norton Smith was easily perturbed by any criticism directed towards the VDL Co. Not that Ritchie was reported as saying anything untoward about the VDL Co. On the contrary, he was quoted as saying, “but little credit was due to the [VDL] company for their enterprise as they must have seen it was certain to pay”. Norton Smith made it clear that, of course, the directors and shareholders expected the tramway to pay. Otherwise, they would not have invested nearly £50,000 in its construction. Norton Smith stated that the VDL Co. came “to the rescue” of the MBTM Co. when no one else was interested in forming a company to construct a tramway.

Norton Smith also took offence to comments that the dray road was closed by felled trees during the tramway construction. He also dismissed the claim that the VDL Co.’s revenue on the tramway was £25,000 a year. He wrote that the VDL Co. would gladly lease the tramway to the MBTM Co. for half that rate, and they could get all their tin delivered to Emu Bay for free and leave a balance of £500, which could pay for the freight to their Launceston smelter.

William Ritchie responded quickly:

“…although it would be with great reluctance that I should allow myself to be involved in a newspaper correspondence…yet the extent to which Mr Norton-Smith has presumed on the credulity and simplicity of your readers compels me to make a few remarks on his letter”.

Ritchie invariably started his letters with similar words, indicating his reluctance to reply to Norton Smith and appealed directly to the readers. Still, because Norton Smith wrote “numerous inconsistencies, misleading assertions, and illogical conclusions”, he felt compelled to respond even though these flaws “must have been obvious enough to those of your readers who had a correct knowledge of the facts of the case”.

Ritchie reiterated MBTM Co’s main gripe that the rate of £4 per ton on ore freight was excessive. He knew the VDL Co. were on the nose with the locals at Waratah, who relied entirely on the outside world for their goods. Ritchie chose to exploit this by shifting the argument to other factors like the cost of living and the lack of comfort for the passengers.

Ritchie claimed the freight charges for small parcels were too high as “it cost more than their price to send a dozen eggs from Emu Bay to Waratah”. He also provided an example of potatoes selling for 25 shillings a ton on the coast, but residents at Waratah couldn’t buy them for less than £9 per ton.

His description of the passenger carriage was no doubt based on his first-hand experience:

“At a very moderate cost comfortable carriages with first and second class compartments, and one for smoking, might be placed upon the line, instead of the cramped, dirty, and in every way uncomfortable vans or trucks into which passengers are now squeezed together, with packages of merchandise, carcasses of mutton, tin ore, and sundries of all sorts”.

Norton Smith argued that the fares charged for passengers were the same for the distance between Emu Bay and Latrobe (36 miles), where the carrier didn’t have to build the road or fund its maintenance. However, he was less vocal about countering passenger comfort and safety arguments. After all, the VDL Co. had little experience as a public transport company. Their focus was delivering tin ore to Emu Bay, not the comforts and well-being of passengers. However, they provided loose cushions placed on seats as the occasion required, for the “better class of passengers”.

Norton Smith started his response to Ritchie trying to elicit public support away from the MBTM Co.:

“..he [Ritchie] accuses me of presuming on the credulity and simplicity of your readers…There was no presumption on my part, I merely made a plain statement of the circumstances which had led to the construction of the tramway, so far as they had come within my knowledge, and made some few remarks upon the rate of freight. With regard to the public confidence felt in the future of Mount Bischoff, of course Mr Ritchie had a better opportunity of forming an opinion than I had, but I must remark that the public had a strange way of expressing their confidence when they allowed M.B.T.M. Co’s shares to be hawked at about thirty shillings each and under for paid up stock”.

Norton Smith argued strongly that the success of the tramway was linked to the fortunes of the mine, and as the tin resource became depleted, so too would the profitability of the tramway as it had no other resource goods. Transporting other goods was simply incidental to the functioning of the mine, including passengers who were mainly workers at the mine.

“The letter of Mr Norton Smith…appeared to me to carry its own refutation in the baseless and reckless statements outlined in it, and in its evident want of that candid spirit with which the discussion of public questions should be approached”.

While he believed Norton Smith was not worthy of a reply, he nevertheless wanted to “point out as briefly as possible, and by way of illustration only”, a detailed response and refutation to Norton Smith. Ritchie accused Norton Smith of using the post hoc, ergo propter hoc argument to support his assertions that the MBTM Co. was in financial difficulty because it had to borrow money at 14 per cent interest to continue mining tin. While Norton Smith was a shareholder of the MBTM Co. and kept a close interest in its operations, Ritchie questioned the “reasonable grounds [he had] for making a statement of such serious importance”.

Ritchie believed that the:

VDL Co. should base its calculations for a certain revenue from its tramway, upon a large business conducted at moderate charges, upon the principle of making small profits and quick returns yield a handsome income from extensive operations. This is the kind of thing every business man knows”.

It was clear that Ritchie believed the VDL Co. should bear all the risks for making money, even though it had little room for error in terms of its financial situation, while the MBTM Co. should be free to increase its profits at the expense of other businesses. Given that he was the Chairman of the MBTM Co., it was no surprise he argued that way.

The fact that he “reluctantly” sought to achieve his aims and gain public support was a targeted strategy to discredit the VDL Co. The VDL Co. already faced antagonism because it was seen as a company run by wealthy aristocrats living in England that possessed too much power in the north-west of Tasmania due to its extensive landholdings.

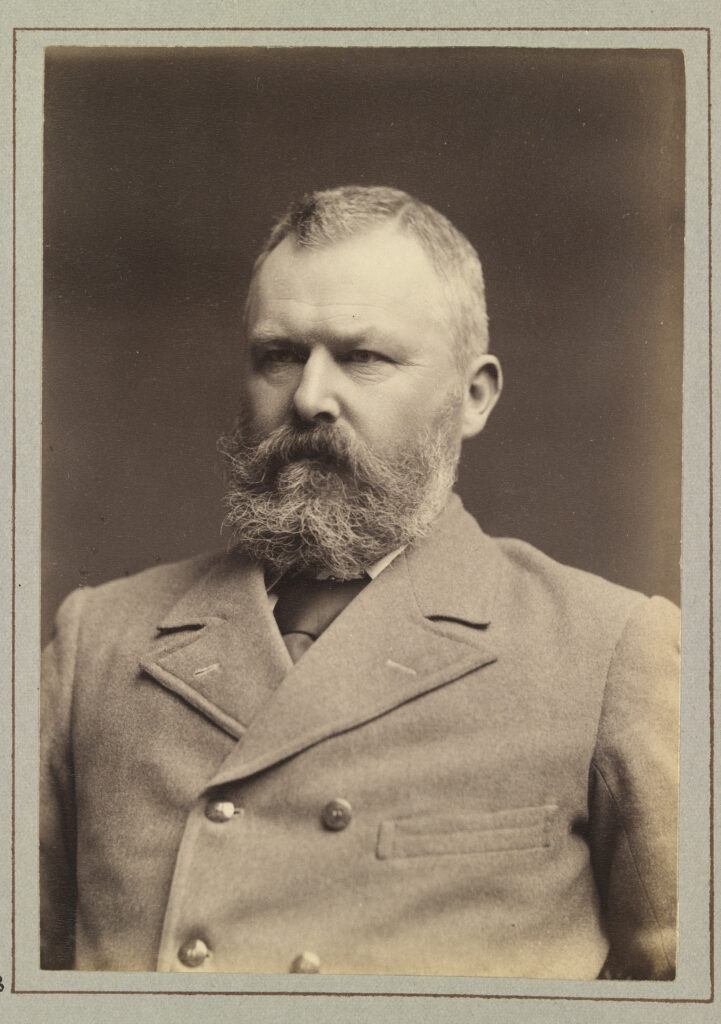

Norton Smith was a well-respected and widely known business operator in Tasmania who sat on the local Marine Board and was a member of Parliament. He tried to make himself a man of the people and extended his dealings and business trips far and wide to maintain the VDL Co.’s standing in the community. He was always quick to defend the company from criticism.

These letters form an interesting part of the history of both companies. It is not often that two highly influential and well-known businessmen engage in a public argument, denigrating each other in full public view. Ritchie was adept at keeping the discussion away from the rewards shareholders of his company were earning, which reflected larger profits compared to the struggling VDL Co.

In the court of public opinion, the VDL Co. hardly stood a chance to gain sympathy regarding finances, despite being the poorer of the two companies. This was something Ritchie knew and exploited to full effect.

Always a pleasure to read your stories.

Thanks Peter. Glad you enjoy them.

What an amazing story.

A good story, well written and enjoyable to read.