As mentioned in my blog on Dick de Boer, the main reason for my employment by Associated Forest Holdings (AFH) in 1975 was forest insect pests.

By the 1970s, the company was starting to become concerned about the ability of its forest estate, and particularly the freehold property of Surrey Hills, to provide an on-going supply of short fibre for fine paper production by the Burnie pulp and paper mill. The main forest species was Eucalyptus delagatensis and natural and assisted regeneration of this species was slow, leading to experimentation with plantation of this and other eucalypt species. A severe outbreak of a gum-leaf defoliating beetle, Paropsisterna (Chrysophtharta) bimaculata in 1972-4 put further pressure on the need to find answers to the fibre supply issue.

Forest Entomology, though a well-established discipline in North America, was in its infancy in Australia, with the exotic pest of Pinus radiata, Sirex Wood Wasp (Sirex noctilio) the only serious forest insect problem in Tasmania. By the 1970s this problem had been largely solved by the introduction of natural enemy parasites (“Biological Control”) and better plantation management, although from time-to-time outbreaks persisted. With the move towards intensified native eucalypt regeneration and plantation it seemed as though a whole new pest and pathogen Pandora’s Box would be opened. Managing native pests is not so straight forward, as the biological control option is much less effective since the natural predators and parasites are already co-existing with their hosts.

It is in the nature of most pests and pathogens to flare up into population outbreaks and then subside. The factors leading to such population cycling are complex, involving weather patterns, host tree stress, and natural parasite and pathogen populations which are also themselves cycling. As a result, efforts to protect forests or tree plantations are often reactive, rather than proactive, leading to loss of resource due to delayed control, unnecessary expense, and over-use of toxic pesticides.

The introduction and development by AFH and subsequently North Forest Products, of a significant plantation estate of the exotic Shining Gum, Eucalyptus nitens and the native Tasmanian Blue Gum, Eucalyptus globulus, provided an opportunity to develop a proactive forest health management programme by the late 1990s that involved detection and monitoring of a variety of potential and serious pests of these two plantation species. Not only was there the risk of loss due to endemic pests, but some exotic pests such as the Guava Rust fungal pathogen (Austropuccinia psidii) posed a potential risk to eucalypts. This pathogen was subsequently detected in Australia in 2010 and now affects a wide range of native myrtaceous species including eucalypts.

Over a five-year period, my assistant, Tim Hingston, and I undertook 289 visits to company owned or managed E. nitens (169 visits) and E. globulus (120 visits) plantations aged from one to twenty years throughout Tasmania. We identified 45 different pests and pathogens (35 on each host tree species) either by the presence of the causal organisms, or by the symptoms observed and recognised on the host trees. The identifications included 28 insect pests and 17 fungal pathogens. The insect pests were classed as defoliators (13), sap-suckers (8), borers (4), leaf-miners (2) and gall-formers (1), and the fungal pathogens classed as leaf diseases (13), stem cankers (2), shoot diseases (1), and root diseases (1).

We were able to plot occurrence of the more frequently encountered pests and pathogens against age of the younger plantations, up to 7 years old, which included the bulk of the plantations we visited. This is an interesting phase of plantation development as both species undergo a significant foliage change from “juvenile” to “adult” foliage, a condition known as heterophylly. Apart from significant changes in leaf morphology and disposition, there are probably also changes in leaf biochemistry, particularly with the essential oils that provide a level of defence against leaf attack. We found that the normal age of foliage change for E. globulus plantations was around three to four years, and for E. nitens plantations, around four to six years. When we looked at the most frequently occurring pests and pathogens, we found some interesting patterns of attack. Gum-leaf beetle (main species Paropsisterna bimaculata and P. agricola) attack became much more common after plantations had achieved adult foliage. The same pattern also occurred with Eucalypt Weevil (Gonipterus scutellatus) and gum-leaf Skeletonising Moth (Uraba lugens). However, Autumn Gum Moth (Mnesampela privata) preferred plantations with juvenile foliage, with a significant drop off in occurrence in plantations with mostly adult foliage. The two most common leaf pathogenic fungi, Crinkle Leaf (Mycosphaerella sp.) and Phaeothyrolium sp. Most frequently occurred in plantations at the point of foliage change. This could have been due to canopy closure in these plantations where there were still significant amounts of more susceptible juvenile foliage. These observations of pest and pathogen attack susceptibilities allow for better targeted monitoring programmes.

Monitoring of an outbreak is critical if effective control is to be implemented. This was illustrated on several occasions during the course of my career with AFH/North Forest Products. One particular case was outstanding. Autumn gum was in outbreak in Surrey Hills in the mid-1990s. A two-year-old plantation of E. nitens came under heavy attack. Due to a difference of opinion as to whether the plantation should be aerially sprayed with insecticide, half of the plantation was sprayed, and half left unsprayed. Defoliation continued in the unsprayed portion with the spraying boundary soon becoming quite obvious. Plots for measuring plantation growth rate were established in sprayed and unsprayed sections. Six years after the defoliation event the mean annual increment (MAI) in the sprayed section was 12 cubic metres per hectare per annum, compared with an MAI of 3.5 in the unsprayed section.

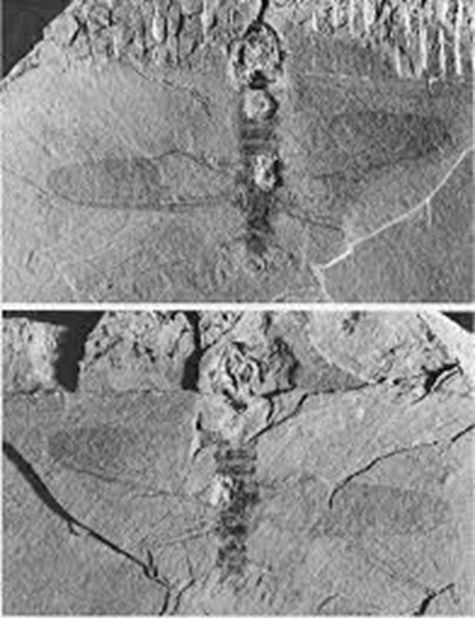

On a lighter note, forests managed by AFH have a very long association with insects. A spectacular discovery of a fossil of an ancient insect was made in the Hellyer Gorge area in 1974, with support and assistance provided by the company. The upper Carboniferous (approximately 300 million years old) “Wynyard Tillite” was known to contain bands of early plant fossils and arthropod trails. A party of geologists from the University of Tasmania decided to try and find more evidence of the arthropod(s) involved. After a fruitless day of cracking open rocks, a last rock was cracked by the parked vehicles as preparations were being made to leave. A near perfect fossil of dragonfly-like insect was revealed. This insect, which lived in a very cool fresh-water environment, was probably co-existing with amphibians, at that time the most highly evolved vertebrates. The discovery of this fossil has led to the erection of a whole new sub-order in the insect evolutionary tree, the Neosecoptera. The specimen itself has been named Psychroptilus burretiae, the specific epithet honouring its discoverer.

Who knows what more exciting discoveries await budding scientists within these forests?

Further reading:

de Little, Dave (2002), “Forest Health – a proactive approach to pest and disease problems in Plantation” Australian Forest Grower, Vol. 25, No. 3, Special Liftout No. 61

de Little, D. W., Foster, S. D. & Hingston, T. L. (2008), “Temporal Occurrence Pattern of Insect Pests and Fungal Pathogens in young Tasmanian Plantations of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. And E. nitens Maiden” Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Vol. 14(2): 61-70.

Riek, E. F. (1976), “Neosecoptera, a new insect suborder based on specimen discovered in the Late Carboniferous of Tasmania.” Alcheringa 1, 227-234.

Great read. Thank you David and Robert for creating a forum where knowledge and experiences can be shared.

I’ve always thought that research delivers the best outcomes when researchers and operations staff work closely together. Loved the story about the fossil discovery!

In my younger years I travelled often through the forest, but was never aware that problems like these existed. Very interesting to read.