Introduction

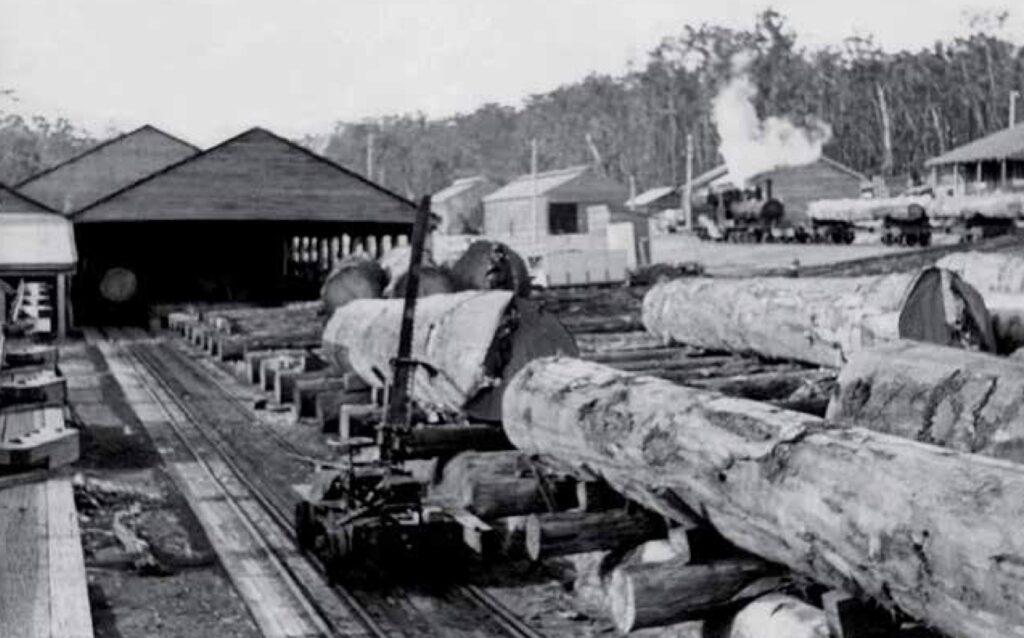

The south-west forests of Western Australia have a rich history in timber utilisation, being one of the longest traditional industries in the state. Several timber towns that housed the timber workers and their families were established in the Darling Range close to the newly constructed Perth-Bunbury-Bridgetown railway line to utilise the timber from the jarrah forests. One of those was at Holyoake, near Dwellingup, where the first sawmill operated by State Sawmills started in 1911.

Timber operations in the karri forests began around Karridale south of Margaret River. It was close to the coast where timber jetties were built at nearby Flinders and Hamelin Bays, near Augusta. A timber entrepreneur from Adelaide, Maurice Coleman Davies, won a 42-year lease at Boranup in 1882. Two-thirds of the land was forested with jarrah and marri, and the rest with karri. Davies was after suitable timber to cut into railway sleepers for a contract he won to build part of the Adelaide to Melbourne railway. He built four sawmills and a town at Karridale, centred around the Boranup forests. However, inadequate forest regulation on cutting timber, meant Davies quickly cut out the supply, and his mills eventually closed.

The opening of the railway line from Perth through to Manjimup in 1912 led to the gazettal of a town, and Wilgaarup Karri and Jarrah Company (later Millar’s) built their first sawmill in the area at Jarnadup (later called Jardee), followed by State Sawmill’s mills at Deanmill and Pemberton, which were originally built to supply sleepers for the Trans Australia Railway.

While Shannon was identified as a potential site for a sawmill as early as 1910 because of its magnificent karri forests, it was one of the last areas to be opened for logging in the south-west, mainly due to its inaccessibility and the timber stands remained virginal until the late 1940s.

The only access to the area was a sandy track blazed through the forests, which later became the main highway. The dairy farmers from the Manjimup region and further north at Bridgetown drove their cattle on this track to the south coast in summer to graze on the pastures and heaths found on the coastal land stretching from Augusta to Walpole. It saved them from hand-feeding their herds and allowed their dairy pastures to regrow after the spring rains.

By the time World War II started, State Sawmills ran eight mills throughout the south-west. They were a significant supplier of timber for building projects, particularly houses. However, the sawmill at Hakea was about to close due to a lack of resources nearby. After WWII, there was an acute shortage of houses around the country, and the demand for building materials was robust. The Commonwealth asked the Western Australian government to keep the cut of timber above the determined sustainable levels. Most of the northern forests had been cut over, so the focus shifted to the forests further south. Five new mills were built in the south in the 1950s.

The significant area of the tallest and finest karri trees near Shannon was part of the push to supply the post-war building demand. In 1947, plans were developed by State Sawmills to construct a sawmill and a settlement in the heart of the forest on the Shannon River to cut timber sourced from the Shannon catchment.

Birth of a town

The site chosen for the sawmill and town was on the southern side of the Shannon River in a picturesque location. The settlement was west of the later alignment of the main highway. North-east of the settlement, and east of the highway, was a stunning granite rock outcrop called Mokares Rock which provided a scenic backdrop to the town. Shannon was one of Western Australia’s earliest towns to benefit from town planning, designed and planned in a U shape.

When the town of Hakea closed in the early 1950s, many of the workers and their families were transferred and relocated to Shannon, 54 kilometres south of Manjimup. They were supplemented by government-sponsored post-war migrants from eastern Europe, contracted to work for a minimum of two years before they could move and work elsewhere.

Shannon was the State’s remotest forest district and the township the most isolated in the south-west. The mill community required a fair degree of self-sufficiency to survive. Provision was made for 90 mill houses, and at its peak, the town hosted a nurse’s station, post office, hall, bakery, butcher, church, general store, school and mill office. There was a large central park, a town hall, and a town oval with a cricket pitch on the river flat.

The Mill railway

After deciding to build the state’s largest sawmill at Shannon River, a new private railway line was constructed as an extended branch of the Pemberton-Northcliffe section of the Western Australian Government Railway, which had opened 14 years earlier in 1933. Starting from the Terry siding, the new line was 21 miles long and took quite a while to construct, which is not surprising given only eight men with a pick and shovel carried out the initial earthworks in the more open areas. From February 1948, a bulldozer was used in the heavier karri country to cut around the roots. Sometimes there were minor deviations to the original surveyed route to avoid large karri trees. On one occasion, a karri tree fell on the dozer’s cab, luckily without injuring the driver.

Wartime rationing was still in place, and petrol and materials were in short supply, making the task challenging to keep to schedule. The track was eventually completed in October 1949, ahead of the mill itself. The smokestack for the sawmill was delivered by rail in three sections.

After the line crossed the Deeside Coast Road near the famed fire lookout in the Boorara Tree, it entered mainly karri stands. Before introducing road haulage, four spurs ran east and west of the mainline on the final approaches to Shannon River. The line continued beyond the town to the east as a logging spur line. However, as petrol rationing was lifted and trucks were larger and more readily available, there was a move away from logging railways to haul timber to the sawmill.

The sawmill, however, continued to use rail to transport sawn timber back to the interchange at Terry. The daily train ran from the mill to Terry and returned until mid-1963, when the railway was discontinued following the sawmill sale to Hawker Sidderley Building Supplies (HSBS).

The railway had an even shorter life than the mill and the town, operating for a mere 16 years. Not much is left of the original line apart from the odd cutting and low embankment. Today, forest and bush have taken over most of the line. Some old mill spurs became logging and fire breaks, but even most of those have disappeared to the silent bush invasion.

The SSM No. 7 locomotive that was bought by State Sawmills after the war to service the line was transferred to the Pemberton Mill, where it worked for a further seven years. It is now resting and preserved in a park in Pemberton.

Forestry operations

The Forests Department were quick to set up their Divisional office at Shannon. The first professional forester was Phil Shedley. As the Divisional Forest Officer, he was responsible for the various forest management tasks such as the designation of cutting areas, tree marking and control of harvesting operations, building hundreds of kilometres of roads and bridges and the appropriate silvicultural practices to ensure regeneration of the forest.

The Shannon was the last of the State Forest areas to be developed for timber harvesting because of its hitherto lack of access. While 37 per cent of the Shannon catchment contained karri forest, only nine per cent of the total area was pure virgin karri forest. But it was access to forest stands that was the critical issue.

During his time at Shannon, Phil developed the “all stringer bridge” to cross creeks as part of building roads to access forest stands. Instead of laying stringers across the creek on bed logs where the timber decking was attached, he came up with laying squared stringers side by side across the river or creek. They were held together by long steel rods. His idea eliminated the need for timber decking, and they soon became the standard design for bridge construction in the karri forests. Phil also designed and led the construction of fire lookouts in the area, including at Mount Frankland.

Phil described his achievement as being “efficient in supervising house building” in a rather unassuming and modest appraisal of his time at Shannon.

Barney White replaced Phil in 1958. Barney was a well-respected forester who knew the karri bush well. He was the first to work out a method of predicting the seeding cycles of karri based on field surveys of bud initiation and flowering. This was very important in organising regeneration programs to coincide with the availability of viable seeds. His published guidelines on the topic were necessary management aids for other foresters. You can read more about Barney in this great memoir.

John Sclater was the new Officer in Charge in mid-1962. He remained at Shannon until mid-1966. It became clear during his time there that the Shannon sawmill had a limited future as it was by then an old-fashioned mill. The introduction of modern logging gear and trucks made it more profitable to transport logs to the Pemberton Mill, which was modern and worked two shifts. It was also getting difficult to attract staff to live at Shannon. John began plans to move the divisional office to Walpole and organised the appointment of a second field staff officer to support Jack Rate, the Forester in Charge at Walpole.

While some of the very best karri forests are in the Shannon state forests, the silvicultural practices remained the same as elsewhere, even though there was a greater mixture of pure karri, mixed jarrah and marri, and open swamps, wetlands and sedgelands known as “flats” compared to other areas further north. Until the 1970s, the primary silvicultural treatment was group selection cutting, where regeneration burns were delayed until the seed was ripe and available in the crowns. This sometimes meant a wait of up to four years. Then, the logging coupes were scrub rolled and a perimeter track established in preparation for the burn.

The Shannon forests carried some old fire-damaged areas from pre-WWII that originated principally from coastal burning on cattle leases. These areas favoured the introduction of clearfelling with seed trees, which was introduced in the 1970s. Of importance were three fires that affected the Shannon forest during management control by the Forests Department. The first was the Boorara Fire which started on the coast near Northcliffe in the early 1950s and burnt a large area (including the Shannon forests) over three weeks. Lightning strikes started the Dog Road fire in January 1961, and under the influence of hot northerly winds, a crown fire ripped through the central part of the Shannon River catchment. The second Boorara Fire in March 1969 burnt across the Shannon forest almost to Deep River, under the influence of high temperatures and gale force north-westerly winds.

Those three severe wildfires, plus the indiscriminate burning before the 1950s, killed stands of mature karri forest. They were the primary reason for the recommendation in 1976 by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) that the central areas of the Shannon River catchment should be logged and regenerated before any reservation.

From the late 1940s until 1983, 5,200 hectares, or 25 per cent of the karri forest and about 17 per cent of the jarrah forests, were harvested and regenerated in the Shannon forests.

The “surprise” decision

The State Sawmills (then known as State Building Supplies) were sold in 1961 and bought by HSBS. They took over the Dwellingup, Shannon, Pemberton, and Deanmill sawmills. It has been stated that the sawmills were given to HSBS by Premier Sir Charles Court, happy to introduce to Western Australia a British company with a background in aircraft manufacture he considered a “modern and exciting business”. They acquired the sawmill assets for next to nothing, only paying for the value of the sawn timber in the yards.

However, according to retired foresters I spoke to, they were “ruthless bastards” closing mills and shutting down shifts and sacking staff near retirement. The Forests Department was required to employ many of them. Head Office staff were called in and given their final pay and marching orders.

Within this context, a decision to suddenly close the ageing Shannon sawmill was made. Some believe that the decision to grant a woodchip licence to HSBS’s competitor Bunnings was the primary catalyst for the closure. However, woodchipping didn’t commence until 1975, and HSBS were already well on the way to divesting the assets they acquired cheaply.

Noel Ashcroft was the last DFO appointed at Shannon in March 1969. He replaced Don Keane, who had been there since 1966. His primary focus was to move the Shannon River forestry settlement after the sawmill had closed. The mill houses were sold and removed into Walpole to consolidate the forestry resources in one centre and create the new Walpole Forest Division. In addition, Noel worked with Jack Rate to secure sites for housing at the east end of town, the new office and operations yard and workshop, also at the east end of town behind the sawmill.

The background machinations that led to the reservation of the Shannon Basin

In the late 1950s, the federal government set up the Australian Academy of Science (AAS) based in Canberra. One of its tasks was to assist the states in setting up a national system of national parks and nature reserves. The AAS developed criteria for the “perfect” reserves system, outlined in a series of papers presented at a symposium held in Canberra in October 1974. Sub-committees were established in each state to investigate proposals and make recommendations. The Western Australian sub-committee provided a report in 1962 with several recommendations for permanent reserves, but the state government ignored most of them. Later, in 1969 the state government created a Reserves Advisory Council with similar terms of reference to the (AAS) and several of its recommendations for reserves were implemented. In 1971, the Environmental Protection Act was passed, and it created the EPA to “consider and initiate the means of enhancing the quality of the environment”. A Conservation Through Reserves Committee (CTRC) was formed to review and update the AAS sub-committee’s report and recommendations.

The introduction of the Wood Chipping Industry Agreement Act 1973 was the impetus for dedicated forest protest organisations as they opposed what they called the “destruction of forests through woodchipping”. The leading group was The Campaign to Save Native Forests (WA) (CSNF), which initially was not opposed to woodchipping and clearfelling but objected to the scale of the proposed operations. While the EPA and the Forests Department agreed that not more than nine per cent of the Shannon River catchment would be logged in the first five years of the woodchip licence period, CSNF were eventually successful in excising the Shannon catchment from the woodchip area.

Meanwhile, the Forests Department managed to formalise its commitment to multiple use forestry through an amendment to the Forests Act in 1976. During the 1970s, the Department included the management of other uses such as water, recreation and conservation in its intensive management units or high-quality timber areas. They also began to set aside areas to be managed as reserves, such as the Perup Fauna Priority Area, Dryandra, Ludlow and Boranup. The EPA supported this.

At the same time, the CTRC recommended the reservation of the entire Shannon River catchment, covering 58,000 hectares, most of which was state forest. The idea of reserving a whole forested catchment was enthusiastically adopted by a new breed of environmentalists on the scene. Scientific and amateur naturalists had dominated the conservation movement in the past. Now, overtly political elements were taking over, originating inside the Labor party, the unions and on campuses.

The Forests Department opposed this new recommendation as they believed the CTRC proposal was inferior to their own. It only focused on the karri forest and not the other important vegetation communities, including non-forest ones. The Forests Department also believed that a series of reserves representative of different ecological types was more beneficial than simply reserving a large swathe of land with minimal management input. It was a group of foresters who initiated a proposal to create a large coastal national park on the south coast. Along with Broke Inlet, the D’Entrecasteaux National Park reserved an estuary and undeveloped coastline. However, in the eyes of the environmentalists, that was not enough. They wanted the forested river basin that flowed into the estuary part of this contiguous reserve.

Meanwhile, the CSNF had become adept at avoiding debate with foresters over the management of the forests. Instead, they focussed primarily on garnering public support through public meetings in Perth. A series of broadsheets attacked the forest industry and the Forests Department. The language they used was straight from the student political movement at the time.

The Forests Department decided to incorporate priority areas for biological preservation on state forests in its General Working Plans (No. 86 and 87), which formally applied the principle of multiple-use. As a result, its management objectives and strategies were open for public scrutiny for the first time. Working Plan No.87 was approved by the government in 1982, which included a system of “scientifically selected Management Priority Areas (MPAs) for conservation of flora, fauna and landscape” in the karri belt and, for the first time, a substantial reduction in the sawlog harvest. They were developed by Barney White and described as “Mr White’s vision splendid”. But the plan was strongly opposed by the environmental movement, which wanted to include the whole Shannon River catchment as a permanent reserve.

In 1982, the EPA commissioned Dr Peter Attiwell to review its recommendations for reserves in the karri forests. These recommendations included two MPAs in the Shannon catchment – Curtin and Lower Shannon, which comprised about 40 per cent of the forests in the catchment. He concluded that the “EPA’s recommendations for reservations within the main karri belt were adequate in terms of the biology of the species”.

The CSNF argued that foresters had a narrow view of conservation by focussing on specific and representative stands of forests to reserve, which excluded “important ecosystem functions which maintain the forest and protect the surrounding areas”. Thus, they pushed for a proposal to protect the entire watershed basin of the Shannon River. The term “Shannon Basin” became a symbol of their campaign and included the first use of car bumper stickers in Australia.

The election of the Burke Labor Government in early 1983 was a real catalyst for the reservation of the Shannon Basin. The CSNF was formed by activists who were very active in the Labor Party, being part of the Party’s Conservation and Environment Policy Committee. The 1980 State Conference overwhelmingly endorsed the proposal to reserve the Shannon as a national park. The incoming government’s forest policy included declaring the state forests in the Shannon River Basin and the Forest Department’s conservation MPAs as national parks. They soon announced plans to convert the Shannon state forest into a national park.

However, there were some hurdles before the government could enact its forest policy. The revocation of state forests to national parks required the support of both Houses of Parliament. But the Upper House was dominated by the Liberal/National Country Party. The government also wanted to cease logging activities, so the area could be managed as if it were a national park. It meant the General Working Plan had to be varied. Under the Forests Act 1918, this required the consent of the Conservator of Forests, who was strongly opposed to the reservation of the whole Shannon Basin. The government sought legal advice on how best to achieve its political ambitions. When that didn’t provide the solution they wanted, they simply promoted the Conservator of Forests to Director-General of the Department of Premier. They replaced him with a temporary appointment who didn’t put up any opposition to their political aims.

Logging in the Shannon forests ceased immediately, and planning and construction of visitor facilities began with many of the trails following old tramway lines.

In 1987, the Minister for Conservation and Land Management established a Committee of Inquiry on the Shannon River Basin proposal. Its report suggested that the reservation of the Shannon Basin as a National Park had scientific merit. With the support of the opposition in the Upper House, the Shannon was declared a National Park in December 1988. The site of the former settlement is now a campground. Several reminders about the area’s past can be found there, including fruit trees and signs with historical photos, as well as building foundations.

An idea so pregnant with promise

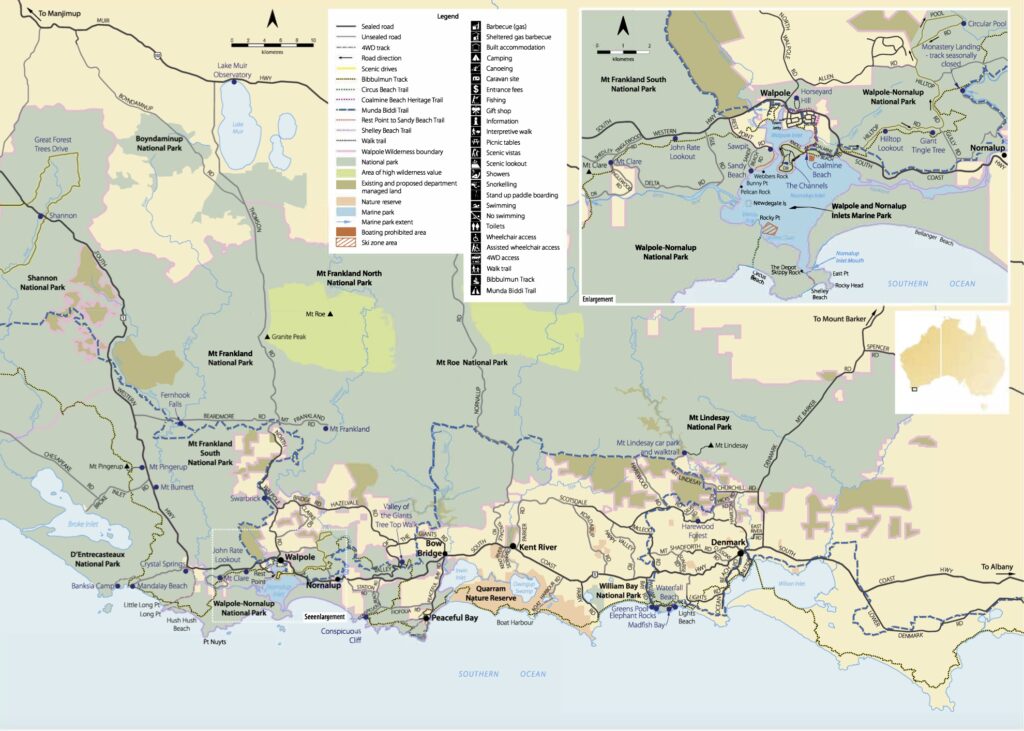

You would think that once achieving their aim of reserving a whole forested catchment, the environmental activists would ease back and revel in their achievement. However, in classic hubristic fashion, they didn’t want to settle just on a national park and inevitably shifted their focus to the next stage. They conjured a wilderness proposal covering a broad “ancient” landscape “under threat”. The proposal even tried to gain the support of local farmers and residents by seeking to integrate the Walpole and Nornalup townships and farming districts into the wilderness area. They coined it the Walpole Wilderness. It was an idea so pregnant with promise that it became fixed in the urban public mind.

According to Wikipedia, the “Walpole Wilderness proposal sought to realise the region’s potential for nature conservation by proposing the creation of a Regional Wilderness Park which expanded and linked existing parks and reserves into a single integrated conservation reserve”. It was a “paradise” of 363,000 hectares covering the vast area of forests between Walpole, Denmark and Rocky Gully including eight national parks. Two areas are called “core wilderness” where access is only by foot or canoe with no marked trails. Remarkably, the wilderness also includes three sites with high visitation levels – the Valley of the Giants with its popular tree walk through the tingle forests, Mount Frankland and its lookout and Swarbrick, all serviced by bitumen roads.

The Walpole Wilderness is merely a conceptual name for a group of reserves adopted by the Department of Environment and Conservation at the urging of environmentalists. It is cringe-worthy reading the justification for the declaration. It is even more embarrassing reading the Management Plan prepared in 2008, which outlines the level of modification to the Shannon forests that make a significant proportion of the Walpole Wilderness non-compliant with the government’s Wilderness Policy Statement.

Now that the Shannon forest has been declared a “wilderness”, a lack of active management has produced the inevitable outcome. The 2016 O’Sullivan fire burnt through thousands of hectares at Shannon National Park, and the magnificent karri stands have been reduced to dead stags and scrub. The fire was started by lightning and burnt through heavy, long-unburnt fuel that was impossible to put out. History was forgotten as the lessons learnt by foresters in the 1950s and 60s, from previous devastating fires, were ignored. Virgin stands survived under the careful stewardship of professional land care by foresters. Benign neglect with very little active fuel management is how they are now managed. Consequently, beautiful virgin stands of karri are being destroyed.

When people venture out of the city once a year to the Shannon Basin to drive on bitumen roads and walk along prepared tracks among the towering trees, they are told they are in an ancient land, all the while listening to the screech of birds, and smelling the damp earth at their feet. It doesn’t mean, however, they are in a wilderness. While some more remote areas in the far south-west might qualify, the cynical declaration of the whole Shannon Basin as part of a wilderness makes a mockery of the process of “protecting” forests and tries to eliminate the rich history of forest utilisation last century. It also puts the forests at risk of peril from devastating bushfires through a lack of active management.

And anyway, doesn’t the declaration of the Shannon as a wilderness support the previous forest management practices that maintained forests that are now recognised as worthy of such adulation? The whole farce reminds me of the car bumper sticker I saw in the 1990s – “the only true wilderness is between a greenie’s ears”.

Where can I get one of those bumper stickers?

I found much of this information very interesting.

However, there is scant attention to the major changes to forest fire management that emanated from the recommendations of the Roger Royal Commission that followed the 1961 Dwellingup fires.

Conservator of Forests, A. C. Harris, commenced a program of large scale prescribed burning over most state forests. This then led to the concept of aerial burning.

The first four operational aerial burns were carried out in 1966 under my direct control, to the north and east of Shannon River. The aerial burning became more common after some workers died lighting a prescribed burn in thick bush in the Shannon River Division.

The next year a further two burns were done further east. This provided major protection of the best karri forests to the south.

It was not until after the Shannon River mill closed that, apart from running the Division, Noel Ashcroft commenced plans to move the Forestry houses to Walpole.

Thank you for this information. I was teaching at Shannon from 1966 – 68. I met my husband there and am currently writing a memoir about his journey with dementia. My interest is in capturing some details about the European immigrants. I was very much part of the community and I remember the families of the children I taught. They would have come by sea and I’m guessing the journey would have been 4 – 6 weeks. For those who arrived prior to the closing of the Suez Canal, perhaps it was closer to 4 weeks. If you are able to shine a light on any of these details, I would appreciate it.

With thanks,

Penny Bingham

Hi Penny. My interest is the history associated with the forests and their management. I don’t have any information on the social history of the settlement, I am sorry. The local historical groups might be able to help. You could start with the Walpole one and see if they can help. They are very active.

Penny — my Dad wrote a book about Shannon a few years ago. It does have some information about the townsfolk, and the immigrants that lived there. If you are interested, I can provide more information.