“If you do not graze and/or burn the country, it will turn into scrub. It will turn into a time bomb and one day it will explode”. Vic Jurskis.

“Burning small patches higgledy‐piggledy every 10 years or so doesn’t have much effect on wildfires”. Submission to the Wambelong fire

Introduction

My June 2022 forestry blog provided a case study into the current mismanagement of forest fuels in the Western Australian karri forests and last month’s blog was a case study of the disastrous 2003 Canberra firestorm.

There are many similar examples in the eastern states. For instance, I have previously written on the 1939 and 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria, the high country fires in Victoria this century, and the 2020 Fraser Island wildfire.

This blog provides a case study in the Warrumbungles following the shocking January 2013 wildfire, which wiped out the park, destroyed 53 homes, and shattered many people’s lives in the local community.

January 2013 was a hot month for New South Wales. A build-up of hot air across the centre of Australia, particularly around the middle of the month, facilitated heatwave conditions in the western districts. As a result, for all but two days in January, forest fire danger ratings in the Coonabarabran area were within the very high category or above, resulting in a significant drying out of forest fuels.

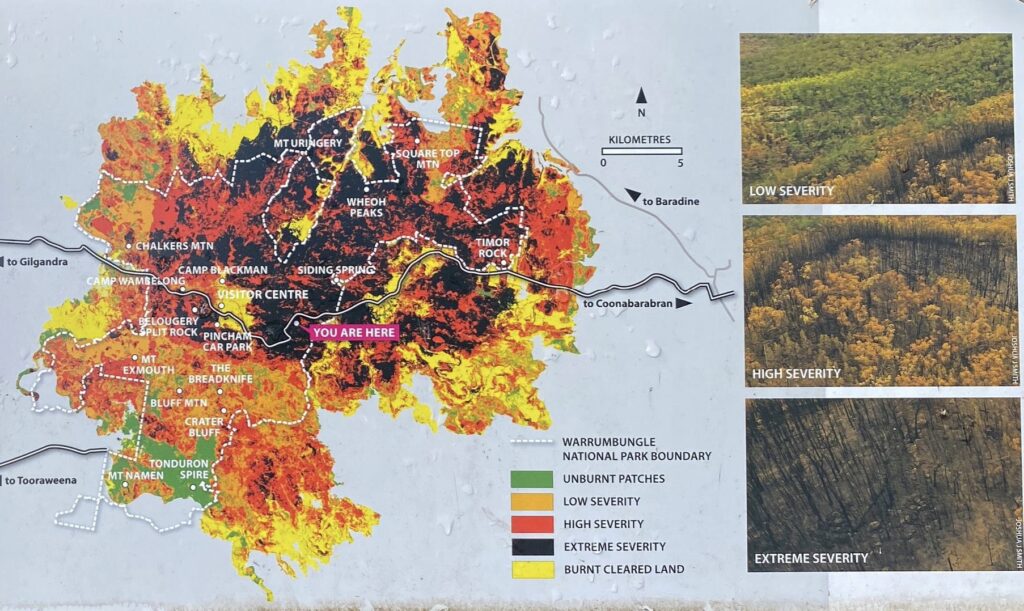

The small Wambelong fire broke out in the Warrumbungle National Park around 4 pm on Saturday, 12 January 2013 and burned out of control around 1:00 pm the following day. It lasted for 41 days burning across the national park, private property and Crown land. When the fire was declared out, over 56,000 hectares were burnt, including 95 per cent of the 23,310 hectares of the national park.

Very heavy rain occurred on 1 February 2013, that led to massive erosion, silting of dams, closing of springs, pollution of water, more damage to fencing and unparalleled germination of darling pea (Swainsona spp), a toxic plant to livestock.

The words of the then Mayor, Peter Shinton, best summed up the situation for the locals:

“Sunday, 13 January 2013, will go down in Warrumbungle Shires history as its blackest day. 53 houses burnt; hundreds of sheds and outbuildings destroyed; miles of fencing down; family heirlooms and memorabilia gone forever and the emotional and financial impacts seriously testing out strong country family relationships”.

The Warrumbungles are indeed a great place to visit. It is a volcanic landscape where volcanos erupted millions of years ago. Erosion of the softer rocks has left several volcanic formations, including the iconic Breadknife, Bluff Mountain and Belougery Spire. Located on the north-west slopes of New South Wales, approximately 33 kilometres west of Coonabarabran, the national park offers some of the best walking tracks and scenery I have experienced travelling around Australia.

A national park was declared over the area in 1953 after leaseholder Alfred Pincham offered a substantial part of his lease for inclusion in a reserve. The area covered the most spectacular features of the range. In 2006, the Warrumbungles was recognised as one of Australia’s most remarkable landscapes when the government included it in the National Heritage List.

It is also an area deemed ideal for stargazing because of its high altitude, low humidity and non-turbulent atmosphere. The Siding Spring Observatory is located on Mount Woorut, bordering the park’s eastern edge.

With this sort of accolade and recognition, you would think it would receive proper professional management to protect its many values. But when you scratch the surface, you find that the official narrative is a lie. The truth reveals a pustule that hides a concerning level of either deliberate neglect or inadequate funding that questions the rationale for the gradual and continued addition of land into reserves under the control of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

This is a story of how poorly planned a national park was to cope with a fire outbreak during severe fire weather. The local community were incensed that such a fire was allowed to occur and called on the government to hold an inquiry to examine policy and fire operations. Despite no loss of life, the coroner also held an inquest into the fire.

A look at fire and fuel management in Warrumbungles in the lead up to January 2013

As an experienced volunteer firefighter and landowner in the area told the NSW Legislative Council Inquiry into the Wambelong Fire, it was a disaster even before it started. Indeed, the Inquiry’s committee was alarmed by participants’ descriptions of the high fuel load in the Warrumbungle National Park before the fire and reports that parts of the park had not been burned in several decades.

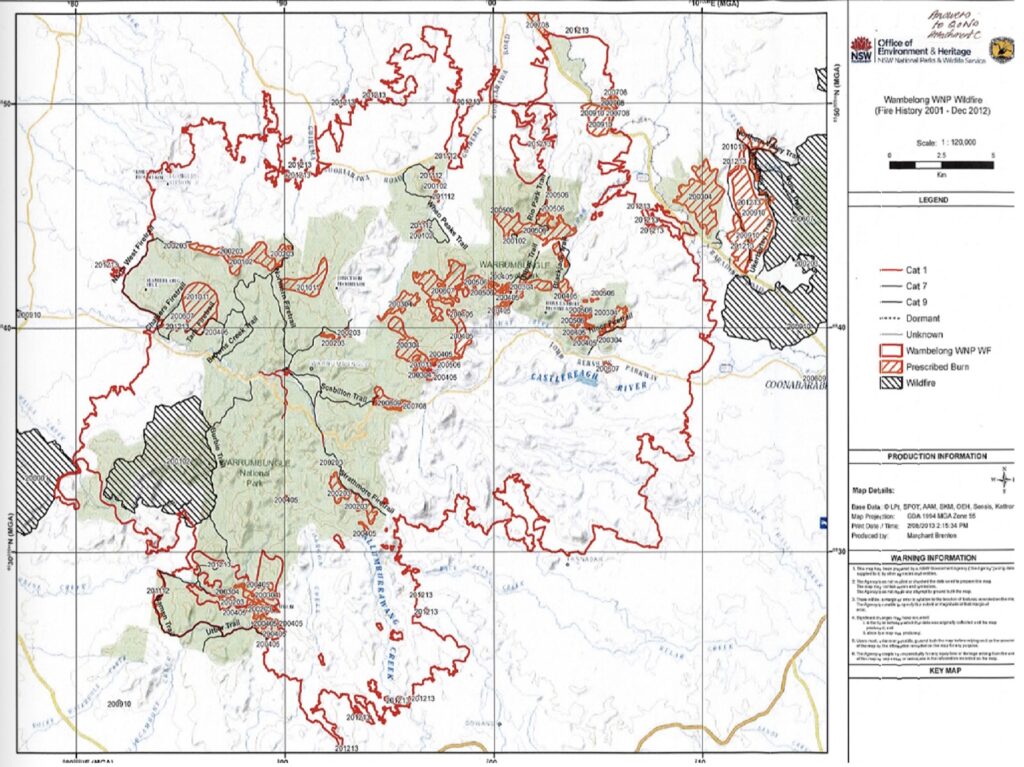

Fire history records show that since the Warrumbungles was declared a national park, a significant fire covering 5,000 hectares occurred in 1967. A smaller fire burnt the central section in 1990 and another in 2002. This followed major fires in 1937 and 1952.

NPWS figures show that in the period 2001-2012, a total of 2,600 hectares were hazard reduced, the equivalent of a little over 200 hectares per year. The Inquiry into the fire was concerned about estimates which indicated that:

“…in the 12 years prior to the fire, only 11 per cent of the park has been subject to hazard reduction burns, representing around one per cent of land per year, which was concentrated in specific zones”,

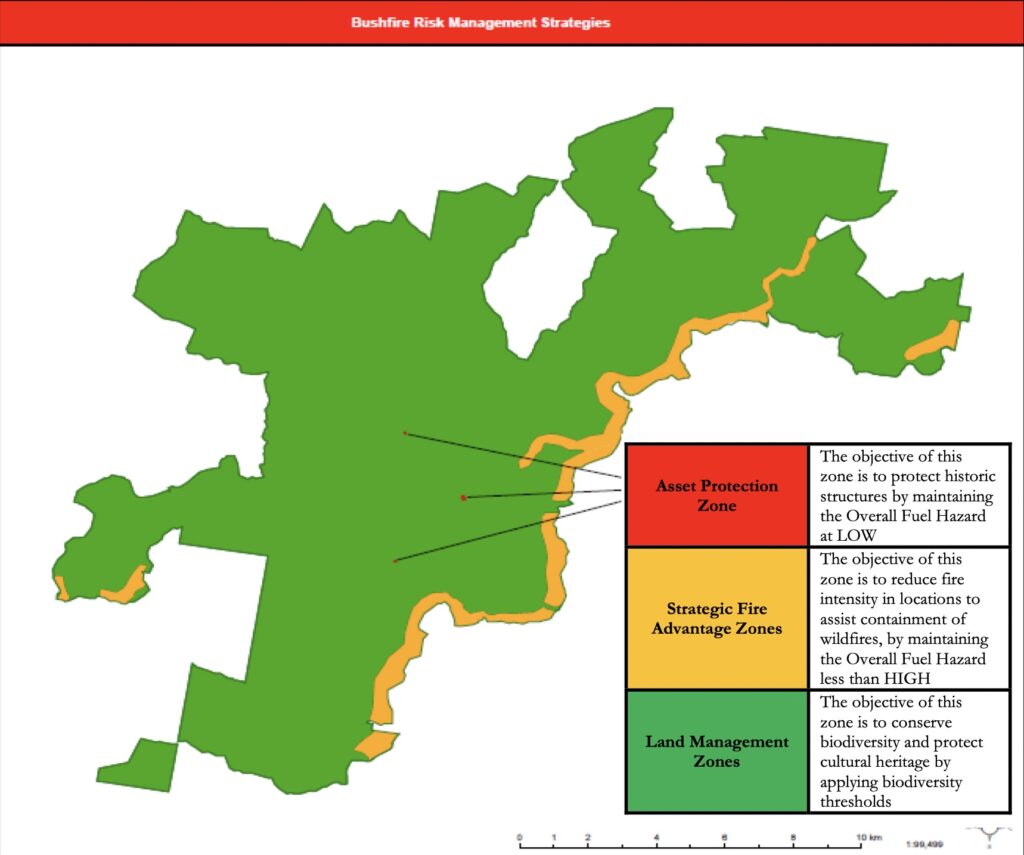

This small amount of burning was justified by NPWS. They say their planned burns focused on “strategic locations near the perimeter of the national park, the aim of assisting in limiting fire movement into and out of the park and protecting neighbouring property along with the key asset of Siding Spring Observatory”.

This is shown in Map 3, where the bushfire risk management strategy for 95 per cent of the park “is to conserve biodiversity and protect cultural heritage by applying biodiversity thresholds”. In other words, burning is a very low priority for most of the park, and there was a firm reliance on containing wildfires by burning a narrow strip along the eastern boundary of the park. However, the events of January 2013 clearly showed how futile that strategy was.

Now in any normal circumstance, you accept that things can go wrong. Ignitions can and do happen during severe fire weather. A good land manager prepares for this eventuality and ensures that the risks of a major fire are minimised. However, the local NPWS staff were ambivalent about the threat posed by the build up of forest fuels.

One landowner adjoining the Warrumbungles, who served several years in the Siding Spring Observatory fire team, questioned NPWS staff about the increasing fire hazard. He claimed they responded in words to the effect:

“…the Warrumbungle is a slow burn park, the trees will not support crown fires, natural decay will control the bush litter, the budget only allows for asset management”.

Dr Christine Finlay, a bushfire expert, has also written about the Wambelong fire here and here. She visited the park only a fortnight before the fire. She had this to say about the fuel levels:

“Beneath towering gums were banks of dead branches, blackberries, peeling bark and other scrub. These banks of undergrowth were an extreme fire hazard capable of producing the hottest fire possible and are known as elevated fuel. Below this elevated fuel was a leaf litter layer 3—30cm deep resting above the non-combustible mineral soil. Research shows that leaf litter layers over 5cm deep would have produced firestorms in extreme conditions in the park’s topography, even without the added heat of elevated fuel”.

During the coroner’s Inquiry into the fire, NPWS officers admitted that the fuel loads throughout the park varied from moderate to high. The Browns Creek area, where the Wambelong fire started, hadn’t burnt since the 1990 wildfire. NPWS indicated that they planned to burn the Browns Creek area in August 2012. However, it never went ahead. NPWS officers blamed a delay in approval from the Regional Manager and the wet autumn.

According to the Coroner:

“Dr Marsden-Smedley believed a probable window of opportunity for the hazard reduction burn in the Browns Creek area was between 14 and 22 May 2012. This depended on NPWS being ready to proceed at that time with the required resources and approvals”.

Indeed, it raises the critical question, just what level of priority is given to hazard reduction burning when land managers know there can be a limited window of opportunity but fail to take advantage of it? The coroner stated NPWS officers “showed no urgency in searching for windows of opportunity”.

On Sunday afternoon, the Siding Spring Observatory was under threat when the escaped backburn became the main fire front. There were also several spot fires ahead of the main front. At around 3 am on Monday, the fire hit the observatory precinct. Fortunately, this damage was relatively minor, with the main telescope surviving. This was due to a targeted hazard reduction program undertaken by Observatory staff after the 2003 Canberra fires, where Mount Stromlo Observatory was lost.

It provides a stark example of how fuel reduction burning can make a significant difference in protecting assets. In contrast, the NPWS supposed targeted hazard reduction program on their boundary failed to stop the fire roaring out of the park into the Timor Valley.

My criticism of national park management in Australia is that they are very poorly funded. There is only sufficient field staff to focus on servicing the visitors and their attractions. Staff don’t get to walk in the bush and have little idea of their management area. Instead, they rely on a broad knowledge of the vegetation communities and expertise gained from a few single-purpose research projects that establish plots and measure variables somewhere in the park. But routine walking and traversing in the forest is hardly ever done. I specifically asked NPWS and the Minister to detail what sort of field work staff do. They didn’t answer the question in their response.

This means that fundamental things are not known when they should be, despite NPWS claiming that local staff were well-prepared for the fire season. An example of the poor preparation was when staff had to inspect a fire trail at 11:00 pm on Saturday, 12 January, to confirm it could act as a containment line for a critical backburn operation they planned to do the next day.

Given the NPWS must report on fire management activities at each quarterly Bush Fire Management Committee (BFMC) meeting, it is unacceptable that no one in the district knew the condition of a fire trail in the middle of a fire season. They don’t have hundreds of kilometres of fire trails in their park to keep an eye on and highlights whether any resources are dedicated to preparing for a fire season.

It is patently evident the local BFMC failed in its function and purpose. It became apparent at the Inquiry that at no time did the BFMC, in its official capacity, inspect the state of the park as far as fuel load, the amount of hazard reduction being conducted, or the state of the various fire trails within the park before the fire season, despite those factors being a requirement for reporting to the Committee.

Forester Vic Jurskis, in his submission to the Wambelong Fire Inquiry, wrote that a reluctance to burn by NPWS is based on a culture that first emerged in the 1980s where burning, grazing and logging were seen as ecologically harmful. He argues since that time, most public land in southern Australia has been converted into national parks, which are mismanaged according to this myth.

“…[NPWS] tries to minimise burning across all tenures using a ridiculous, disproven theory that frequent burning threatens biodiversity”.

I experienced this attitude first-hand during my employment with the NPWS in the mid-1990s as a Fire Management Officer. At times, my professional fire experience and integrity were questioned by inexperienced staff at Head Office employed to assess the “Review of Environmental Factors” document I had to prepare for each proposed hazard reduction burn. They would try and find any excuse, using “ecological reasons”, to stop a burn proceeding. Even more bizarrely, I was not allowed to assess the environmental impacts of not carrying out a burn, or if I did, it was ignored.

In one example, they couldn’t come to grips with my proposal to carry out a mild downhill burn and use the fuel moisture differential to prevent it entering the rainforest. They insisted I include a 20-metre buffer to “protect the rainforest”. When I asked how I would achieve that in continuous fuel without constructing a firebreak, they failed to offer any practical solution. They refused to believe my strategy would be effective. On another occasion, a Head Office assessor went to my proposed burn area and claimed she found quoll scats. She said I couldn’t do the proposed burn because of the presence of a threatened species. However, when I subsequently had a look at the scat, I congratulated this “expert” that she had found evidence of foxes in the area!

Reading the transcript from the Wambelong Fire Inquiry, it is clear the attitude or culture within NPWS has not changed since I was an employee in 1996-98. It was confirmed they carried out hazard reduction burns on one per cent of total park estate each year. A question was then put to NPWS that there is plenty of evidence to suggest hazard reduction burning needs to be done over a much shorter frequency than once every 100 years. Their response was, “it depends on the purpose of the hazard reduction burning”. When the obvious was pointed out to them, they responded, “but is it to protect an asset or is it to protect an ecological value or some other purpose” to which it was highlighted to them, “maybe it is to prevent a wildfire” over the whole park. NPWS tried to argue that in the land management zone (which encompasses at least 95 per cent of the park), the frequency of burns is dictated by vegetation thresholds to “keep it within its biological health”. When asked were the level of fuel loads a concern, they responded, “I do not think they were of particular concern”. This is despite Deputy Coroner Hugh Dillon writing:

“…by reason of the high rainfall between 2010 and 2012, there was, in certain parts of the park, a considerable fuel load“.

NPWS attitude towards fire is best summed up in the above exchange. How can anyone seriously argue the park is “within its biological health” when the management strategies (or lack of) contributed to the whole area being razed in one afternoon? Have a close look at the photo below and tell me that the smoke is associated with fuels levels “that were of no particular concern”.

How seriously does the NPWS take its fire management responsibilities?

The NPWS District Manager at Coonabarabran told ABC radio on Tuesday 8 January 2013 that they were facing “the worst weekend of the year with really terrible weather”. As a safety precaution in response to the forecast fire danger that day, no NPWS staff worked in the park. They resumed park management duties from Wednesday, 9 January.

However, it has been alleged that only two staff were on duty on Saturday 12 March – one an office worker in Coonabarabran, and the other, a shop assistant at the Visitors Centre. I specifically asked NPWS and the Minister if the allegation was true. They refused to answer my question and directed me to “the reports of the Parliamentary and Coronial Inquiries into the Wambelong fire”. Neither inquiries answer that allegation and that is why I asked the question. Even more concerning was that no one was sent to the Woorut Trig Point watchtower to detect any fires early based on a requirement of their “operations manual”.

The Parliamentary and Coronial Inquiries differ markedly on how the fire was initially reported. According to the Coronial Inquiry:

“The outbreak of the fire was first detected at around 3.30pm when Jason Clarke observed smoke coming from the Park. Mr Clarke, a serving RFS member at the time, called his team captain Ron Nash at about 3.50pm to report the fire. At that time Mr Nash was unaware of any fire in the Park. Mr Clarke continued driving towards the smoke until he was about 200 metres west of Wambelong campground. At that point he observed the fire creeping up towards John Renshaw Parkway. Mr Clarke again contacted Mr Nash to report his observations of the fire. A number of local people either saw or smelt the fire in the National Park before 4.00pm. For example, at about 3.55pm Patricia and Stephen Fergusson observed a fire north of Wambelong Creek as they approached Wambelong campground from the east. At 4.06pm Mr Fergusson made the first ‘000’ call to report the fire. John Whittall and May Fleming, both NPWS personnel, also saw a fire at the Wambelong campground and reported their observations to other NPWS staff including Rebecca Cass who was the NPWS ranger responsible for patrolling the National Park that day. Indeed, it was Rebecca Cass’s report that led Mr Whittall to drive to the Wambelong Camp Ground to look for the fire in the first place.”

I read in a submission that the initial fire was spotted by a member of the public driving past in her car along John Renway Drive, a public road through the park. Unable to find any NPWS staff, she drove to a property at the eastern entrance to the park, and the fire was reported via a 000 call. Also, it was not made clear whether the ranger was equipped with fire fighting gear and whether she attended the fire.

According to the Parliamentary Inquiry:

“…at 4.20 pm two off duty NPWS staff who happened to be in the park responded to the report of smoke and undertook reconnaissance“.

No mention was made of any RFS personnel at the fire or a NPWS ranger on duty by the government in its submission to the inquiry. The two off-duty NPWS employees first attended the fire after being alerted by the Visitor Centre employee. They then had to leave the fire to get a “fire fighting appliance” and arrived back at the fire just before 5:00pm.

NPWS’s admission that they had to rely on two-off duty staff members who were in the park at the time (one of whom lived in the park) as first responders to the fire is inconceivable, especially when the Bureau of Meteorology claimed it was the hottest January on record for the state. Not one experienced or senior officer was on duty on 12 January 2013, or worse still, the employees on duty were not trained field staff who could attend fires. As a member of the Coonabarabran Property Owners Alliance asked at the Inquiry, “with this situation, one would expect that extra precautions would be put in place, and all National Park staff would be on call alert with all leave cancelled”.

The NPWS Incident Procedure Manual clearly states that the higher the fire danger rating, the higher the rapid response staffing levels. Clearly they were not followed as it took an hour for fire fighting equipment to arrive at the fire.

At the Inquiry, NPWS Chief Executive, Mr Terry Bailey, stated his organisation was well prepared for the fire season. This claim is not supported by the evidence. Why wasn’t an individual in charge such as Mr Bailey, NPWS, or the government held accountable for not following their protocols and not being fully prepared when they knew they were facing “the worst weekend of the year with really terrible weather”? Until someone, or the organisation is, we will continue to see such flagrant disregard for their responsibilities and continuing destructive fires on the scale of the Wambelong fire.

During my forestry career, staff could not plan any leave during the fire season and had to be on duty when severe fire weather was forecasted – everyone was on stand-by. I had to pull out of a planned sailing trip at the Whitsundays one year because the fire season started earlier than expected. Operators were paid to have large machines on floats ready to mobilise as soon as required. Surveillance towers were manned, and the level of preparedness was commensurate with the fire danger. When there was a total fire ban and severe fire weather forecast, we certainly had more than an office worker and a shop assistant on duty.

After only fighting the fire for three hours on 12 January, NPWS staff left the fire leaving two RFS crews to stay overnight to patrol the western and eastern sides of the fire. The fire was reported as “burning in remote and steep terrain and had grown to an estimated 32 hectares”. NPWS decided not to aggressively attack the fire that night, even though they faced persistent extreme fire danger conditions during each day. Instead, they decided to indirectly deal with the fire the next day by carrying out a back burn from containment lines.

During the height of forestry management prior to 1990s, the standard practice was to construct fire containment lines at night either by hand or machine; build fire breaks by hand in remote areas where machinery access is impossible; and carry out thorough ground-based blacking-out in remote areas to prevent fires developing into large damaging conflagrations which, like the Wambelong fire, ended up doing enormous damage to the environment and human assets. The Wye River fire in 2015 and the Harrietville fire in 2013 provide documented examples of allowing very small and easily accessible lightning strikes to get away.

The Victorian Emergency Management Commissioner, Craig Lapsley, told the media in February 2020 that “we are getting to the point where the traditional tactics being deployed are no longer effective”. However, the Institute of Foresters of Australia’s submission to the Victorian 2019-20 fire season highlighted:

“…the former traditional tactics have long since been replaced by a diluted, indecisive and hopeful version that is far more likely to fail. Of particular concern is the partial shift away from direct attack on the fire edge at every opportunity to a far more commonly used indirect attack strategy of falling back to distant control lines with or without backburning and relying on aerial water/retardant bombing in the mistaken belief that it will extinguish fires“.

The loss of using traditional tactics to fight fires has come about because the emergency leaders have no risk management capacity when faced with a bushfire. They rely on the precautionary principle instead, and ultimately bear no responsibility for the consequences of their poor decisions.

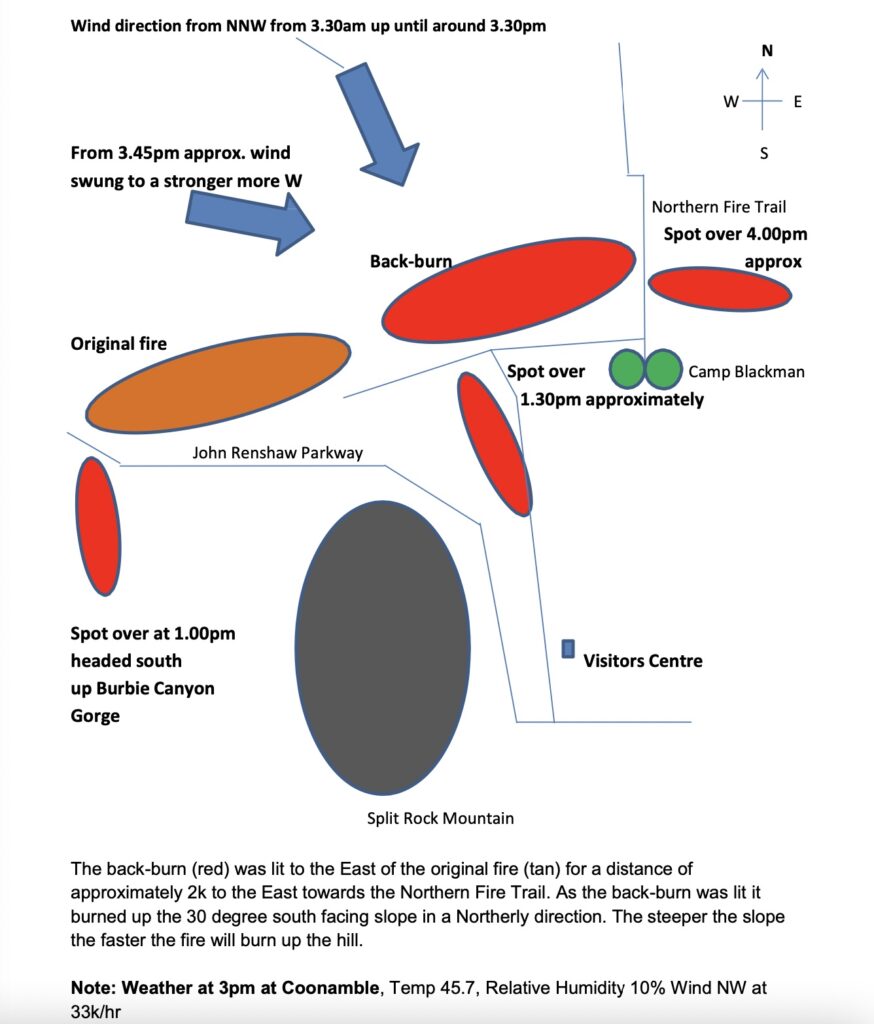

The dramatic development of the fire

Sunday 13 January 2013 was a severe fire weather day with a total fire ban in place. Nevertheless, NPWS decided to carry out a back burn under these terrible conditions, and this deliberately increased the size of the fire. The backburn east of the fire was lit at the base of a 30 degree slope! Added to the risk was the attempt to carry out the burn in old, heavy fuels. Predictably, the first containment breach was on the extreme south-west edge of the original Wambelong fire. It proceeded to burn south up the Burbie Canyon Gorge. Shortly after this, a second spot fire breach occurred at the back burn about one kilometre east of the Wambelong fire perimeter. The Wambelong fire breach was blocked from heading further east by rocky escarpments. Both breaches continued to burn in a southeasterly direction, and the distance between the two fire heads increased.

The back burn breach headed towards the Visitors Centre and easterly across the open country to Camp Blackman. All fire crews were removed from the fire as it was out of control and assembled at the Visitors Centre. Shortly after that, the wind changed westerly, and the back burn fire headed east toward Siding Spring Observatory, exiting the national park and continuing down the Timor Valley towards Coonabarabran.

The Coonabarabran Property Owners Alliance presented an image to the Inquiry taken from the Woorut Trig point at Siding Spring Observatory at 2:30 pm on Sunday, 14 January 2013, by Peter Verwayen using a telephoto lens (see above). The smoke is impeding any view of Split Rock. The image shows the back burn on the right-hand side. The spot over originated from the backburn and grew to an uncontained fire and headed south-south-east towards the NPWS Visitor Centre across open woodland in the centre of the image and became the eastern flank of the fire. Later in the day, a south-westerly wind change made the eastern flank the new fire front, and it ripped through private property in the Timor Valley.

Meanwhile, the Wambelong fire breach continued to the south-east, passing the Grand High Tops towards the communications tower on the park’s southern boundary. After about 4 pm, an extreme wind shift from the south-east turned the 16 kilometres northern flank into the head of the fire, and the fire proceeded toward the village of Bugaldie, causing major havoc and loss of assets. The town of Baradine was also placed on high alert.

In less than ten hours, the Wambelong fire roared through the park and into adjoining land and caused massive damage in the Timor Valley. And in a world first, a reserve management agency managed to burn and destroy its own visitors centre.

Will lessons ever be learnt?

There are several lessons for the NPWS following this fire. First, a lot of the Inquiry focussed on a decision to indirectly attack the uncontained fire on Sunday morning with a backburn, despite a fire weather warning for hot to very hot north-westerly winds. It was found that this strategy was in direct contravention to their fire management plan for the park. It is also incongruous that the backburn was lit at the bottom of a steep hill under those predicted weather conditions. Predictably the backburn became larger than the original fire.

An ex-NPWS employee of over 35 years who worked at Warrumbungle National Park, and knew the terrain, believed the fire should have been attacked directly by ground crews on Saturday night. This was during relatively benign weather conditions, despite the Crew Leader assessing the fire as too active for any ground-based attack:

“With the projected fire run sheet for the Wambelong Fire to run to the NE, this would signal even more urgency to concentrate and carry out an aggressive direct attack on the original fire on the Saturday afternoon and night and the Sunday morning using all available resources to stop this fire run from actually occurring. The correct procedure is not to wait and fight the fire on what may occur, but to be proactive not reactive and put the existing fire out.”

I believe, with proper management of the fuel loads in the years leading up to January 2013, the difficult situation the NPWS fire controllers found themselves in would have been averted and made their choices much more straightforward. However, while it is acknowledged that the structure of the understory has made it difficult to carry out adequate cool burns in the past, there are a multitude of options available for managers to manage fuel levels.

Second, the issue of not having experienced staff on duty during severe fire weather days has been with the NPWS for over 30 years. It all started in Royal National Park. The inquest into the Gray’s Point Fire in January 1983 was held after the tragic death of three volunteers. Six others were severely burnt. The late summer of 1983 was at the end of a prolonged drought period. The coroner found that the park’s Superintendent was on leave in South Australia when the fire started. A ranger of limited fire experience replaced him. She admitted, during the fire, a lack of experience at such an event.

NPWS argued at the Gray’s Point inquest that the Superintendent was allowed to take leave because of improved weather conditions. However, the coroner found otherwise, outlining the weather conditions leading up to the actual fire.

Unfortunately, because no one is ever held accountable for these poor decisions, they continue to happen and we continue to see devastating fires that damage the environment and human assets.

And finally, the Wombelong fire repeated the same mistakes in previous NPWS fires. For example, the ACT Coroner, Maria Doogan, in her 19 December 2006 report on the 2003 Canberra bushfires, stated as her first conclusion:

“The failure to aggressively attack the fire on the first day after ignition was the one factor that led to the firestorm that followed“.

Some of the 2003 fires started at the same time on private property and state forests in New South Wales. On state forests, 12 fires started from lightning strikes, and 11 of those were extinguished and contained and controlled within a day or two. Those fires caused no property loss, no loss of homes and no one died. However, NPWS failed to contain or control any of its fires within 48 hours. Doogan again:

“Once the McIntyre’s Hut fire in New South Wales gathered momentum, crossed the border and joined fires in the Australian Capital Territory, it became inevitable that the resultant firestorm would deliver its fury…”

When will gross and negligent mismanagement stop, and why hasn’t anyone within NPWS been held accountable for the carnage their mismanagement causes? If businesses and farmers face consequences when risk management fails, even jail-time, shouldn’t this also apply to our government officials when they fail? They are never held accountable and continue to easily deflect responsibility because their mismanagement is quickly misconstrued as the unavoidable consequences of climate change. This has to stop. The reason bureaucrats feel the buck stops somewhere else has evolved following years of regulatory reliance on the precautionary principle and their confusion of precaution with prevention. They now operate under a mantra “I might get in trouble for approving something if it goes wrong, but I can’t get in trouble for doing nothing”. If they refuse to competently manage risks, such as severe bushfires, they should be held accountable for that decision.

The aftermath

The postule hiding management inadequacies at Warrumbungle National Park finally burst on the afternoon of Sunday, 13 January 2013. However, reading the evidence from NPWS at the Inquiry, you would think they are the model land managers who could do no wrong. But unfortunately, the questions from the committee members were relatively light. Instead, they allowed the NPWS to simply abrogate any responsibility and blame for the extensive damage the fire caused outside of the Warrumbungle National Park.

The Concerned Property Owners Alliance raised many pertinent questions during the Inquiry, which were not adequately addressed. For example:

- Why were the fire trails not cleared of debris and obstructions before the summer fire season?

- Why were hourly patrols of the park not carried out to enforce the closed status?

- As recommended in the national park operations manual, why was no fire observer stationed at the Woorut trig lookout and fire observation site on Siding Spring Mountain?

- Why were some national park fire appliances empty and not in full readiness?

- Why were only two non-field national park staff rostered to work on this horror weekend?

- The NPWS respondent to the original fire arrived in a car with their family, then travelled up to the Strathmore depot to get a fire appliance, fill it with water, and return to Camp Wambelong. With the delay of 30 minutes at this critical time, the fire had grown, but it was still not going up the hill.

Not surprisingly, NPWS have put a positive spin on the effects of the fire. Displays in the brand new Visitors Centre outline the Wambelong fire in a favourable light and proudly promote a three-year research program to assess the fire’s impact on the park.

However, NPWS researchers are silent on the recovery of several species of fauna that were already vulnerable before the fire, such as the brush-tail wallaby, koalas, spotted-tail quoll, greater glider, bandicoot, various bat and small bird species, turquoise parrot and the Warrumbungle skink.

Yet, when pressed on detailed information about this research program, all the NPWS could organise was a limited presence and absence fauna survey over two years starting four months after the fire and ending in October 2014. No data was collected to find out about population sizes. The most severely affected animals are the arboreal mammals and small terrestrial mammals. As is common for all the national parks in the state, despite claiming to be critical refuges for species, no fauna studies are routinely carried out. Therefore the public has no idea if certain species are declining under their stewardship. For the Warrumbungles, the only information they have on fauna distribution and abundance in the park are rudimentary and crude visitor information surveys, the details of which have now been lost in the fire.

NPWS ecologist Dan Lunney claims, without any scientific evidence, that the Warrumbungles is “too small to conserve a koala population” despite a successful relocation program from Victoria in the 1960s which led to the establishment of a settled population in the park. He cites a decline of koala numbers prior to the fire, due to the millennium drought, and says that:

“…critical to the conservation of koalas [is] to minimise other threats, such as land clearing of prime habitat, logging of preferred food trees, and minimising mortality from other sources“.

However, he refused to acknowledge that a severe wildfire which killed most of the koala feed trees in the park, due to benign neglect and deficiencies I have outlined above by the agency he works for, was not a contributing factor to the lack of sightings of koalas since the Wambelong fire.

NPWS are also silent on the fuel build-up since the 2013 fire. I didn’t see any evidence of any prescribed burning since the fire. NPWS report that the only prescribed burn they have carried out since the Wambelong fire is a very small burn in the Strategic Fire Advantage Zone along Burbie Trail. Their excuses for this are drought and La Niña.

I am not convinced that the problem highlighted during the Parliamentary and Coronial inquiries about a lack of priority to carry out sufficient fuel reduction burning to minimise conflagrations over the whole park has been addressed.

Mr Bailey said at the Inquiry that post-fire research would measure fuel loads in different park areas to guide managers on a review of the fuel management, to ensure NPWS carry out mosaic burning across the whole park. It is now ten years since the fire, and the park has high fuel loads once again.

Researchers should have collected data on fuel loads since the Wambelong fire. If they have, they won’t share it with me, despite my request for that information. All I have been told is that staff carry out “site-specific assessments as part of hazard reduction burn planning”.

I was provided with a copy of the new fire management strategy for the park. It focuses on vegetation management guidelines and an assessment to determine whether a vegetation community is within “biodiversity guidelines”. NPWS have not provided me with the process to determine these “biodiversity guidelines”. The problem is vegetation community boundaries are random and do not follow any containment lines. So it is unclear how they propose to carry out any burns solely within specific vegetation communities. As it stands at the moment, most of the park is designated as “vulnerable to frequent fire”, meaning they have little desire to do any broad scale burning in the near future.

The Warrumbungle National Park is just one example of many National Parks throughout western NSW and the state which carry huge fuel loads. Following the 2013 Wambelong fire, the real challenge for NPWS is to restore a landscape where they can apply a mild fire in the future, unless of course their culture and practices don’t change.

It is interesting that while the national park estate across New South Wales increased from 3.9 million hectares in 1994 to 7.1 million hectares in 2013, it took until 2011 before the government provided adequate funding to ensure appropriate levels of hazard reduction burning were carried out each year. And even then, it was only a funding commitment of $62.5 million over five years called the Enhanced Bushfire Management Program. NPWS managed to increase annual burning to an average of 130,000 hectares, which they proudly claim is a doubling of their burning program before the commencement of the program. Wow, that means for 17 years, NPWS burnt less than one per cent a year of their estate. We have a massive fire issue in our forests, and no wonder Warrumbungles burnt to a cinder in just one afternoon. But NPWS officers don’t see a problem and celebrate the high shrubby fuel loads. I will leave the final words to Vic Jurskis to highlight their misguidance:

“These days we have [NPWS] people who see scrubs as biodiversity. They do not understand that it is just biomass; it is not diversity”.

Rob, there is really no excuse for this continuing neglect during the bush-fire season. It is like giving the Army a month of leave when the enemy is about to invade. It is like farmers going on holidays when harvest is on.

Unfortunately, we have lost the capability to manage large reserves effectively as there is only a skeleton staff to monitor vast areas. We need more “boots on the ground” and less in top management. If the budget is not enough, then some parts of the reserve should be leased back to responsible graziers who can be licensed to act as land managers. That would put thousands of acres into some form of human control.

Also for the very sensitive areas, let’s train up teams of indigenous land managers to be proficient in traditional burning practices during the winter months. It would be instructive to investigate what is actually happening right now with NSW fire management this season?

Admittedly it’s been a very wet summer but when it turns very hot and dry there will again be a heavy fuel load to contend with. Thanks for your work on this story.

Peter, you are being too sensible. You wouldn’t last long in the bureaucracy!

Thanks for another insightful article. It is very sad to see so many parallels with the 2019/20 fire which impacted 77,000ha of the total 88,000ha of Croajingolong NP, and so much more beyond. Your observations and criticism of NSW government and NPWS could well be directed to the Victorian government, Parks Victoria, FFM and DELWP. Your use of the word ‘pustule’ could not be more appropriate for the situation once again developing.