While researching for my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, I came across quite a few caterpillar references in the correspondence of the Chief Agents of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.). The caterpillars were killing off improved pastures planted after clearing or logging and scrubbing operations.

The caterpillar problem was not unique to the VDL Co. It was a problem across Tasmania and the mainland. According to retired Chief Entomologist with the Tasmanian Department of Agriculture, Bob Hardy, the Chief Agents may have been referring to several caterpillar problems.

Caterpillars that are seen during the day feeding on grass stems and leaves are most likely the larvae of the southern armyworm (Spodoptera eridania). The southern armyworm inhabits south-eastern Australia, including Tasmania, and its outbreaks can arise from adults that overwinter in Tasmania. However, large attacks probably occur from swarms of moths that fly across the Bass Strait from Victoria. Outbreaks are sporadic, perhaps once or twice in ten years.

In an outbreak, the number of caterpillars can reach many hundreds per square metre. When the caterpillars become noticeable, they are usually about 15 mm long and are seen in the lower parts of the pasture or cereal crop, feeding on lower leaves. Within a few weeks, the caterpillars feed more on higher leaves and stems, and many stems supporting seed heads per square metre may be severed. In pastures, numbers may contaminate the grass and cause the stock to avoid it.

Some caterpillars are not seen on the surface during the day but are found near vertical tunnels into the soil. They can either be the pasture cockchafer beetle (Aphodius tasmaniae), the corbie (Oncopera intricata), winter corbie (Oncopera rufobrunnea), or Oxycanus grass grub (Oxycanus antipoda). As an aside, Bob first recognised the Oxycanus grass grub as a pasture pest in 1967.

The pasture cockchafer beetle often invades well drained, permanent pastures in lighter soils and drier areas near the coast. During the larval stage, it constructs a vertical tunnel from which it emerges at night to feed on pasture leaves close to the soil. The larvae tend to be a “C shape”, have a black head, and reach 15 mm in length. Small piles of loose soil are usually easily seen on the soil surface due to the larvae constructing the tunnels in which to hide.

The corbie tends to invade the drier areas near coastal pastures. Then, about ten kilometres inland, their place is taken by the winter corbie or Oxycanus grass grub.

The Oxycanus grass grub moths are considerably more restricted than the corbie. They fly under the following conditions – about early May, after dusk and about 30 minutes after rain.

In 1967, Bob was involved in the following observations at Elliott. Rain was forecast to fall on 3 May, but there was no rain, and consequently, no moths flew. The same happened on 4, 5, and 6 May. Finally, just after midnight, on 7 May, steady rain commenced. Twenty minutes later, male moths emerged, followed by females a further 20 minutes later. There were vigorous mating flights and egg laying as the females crawled over the pasture surface. The ghostly looking males and then the females were attracted to bright lights about this time.

The moths had a wingspan of about 60 mm in males and 70 mm in females, and indeed, because of this post-midnight flight, they fulfilled the colloquial name of ghost moths, which was also applied to the corbie and winter corbie adults, which were also attracted to lights.

Finally, some caterpillars are not seen on the surface but are found amongst the roots, and these are the root-feeding cockchafer or scarab beetles such as the red-headed pasture cockchafer (Adoryphorus coulonii).

This group have “C” shaped larvae with yellow or red (not black) heads. When fully grown, they are 20-40 mm long, and the adult beetles are usually brown to reddish-brown. Unlike pasture cockchafers, larvae remain below the soil surface for their whole life and feed on the roots of pasture plants.

These are the most damaging group. The larval stage constructs in the soil a vertical tunnel from which it emerges at night to feed on pasture leaves close to the ground. They primarily attack pastures at least three years of age and, except those with redheads, often within 100 metres of eucalypts. Additionally, they are common prey of bandicoots and crows, which frequently roll back the damaged and, therefore, almost rootless pasture searching for the larvae.

The first reference by the VDL Co. to caterpillar problems was in 1888 when then Chief Agent, James Norton Smith, wrote:

“We have been again unfortunate with the first clearing (now called Emu Bay Forest Farm). I shut up 128 acres of it for seed, for supply of the Ridgley clearing, and had a splendid crop, but the caterpillars have destroyed nearly the whole, as usual they came in just as the seed was ripening, and I was only able to reap 33 acres, and even this was attacked, the balance they so destroyed as to make it valueless”.

The following year he reported:

“At Ridgley the feed grew badly & caterpillars came in millions & swept off what feed there was, so that I had to clear out nearly the whole of the cattle to Woolnorth; to prevent a recurrence of these long drives I purpose taking possession of St Mary’s Plains in March 1890 & thus have a rough run on to which I can turn cattle in cases of necessity”.

In late February 1892, the Ridgley farm suffered a large fire close to the railway line. It was most likely caused by a spark from a locomotive on the line. The fire spread rapidly under a strong wind spreading across dried grass killed by the caterpillars and into timbered areas. The combination of the fire and caterpillars left little grass for stock until the autumn rains.

Norton Smith became increasingly frustrated with the effects of the caterpillars, not being able to harvest seed from their crops for future sowing:

“The Court, having had its attention drawn to the supply of seed, may wonder why it has not been harvested from the Company’s land instead of being bought hitherto. The reason is this, there is almost an absolute certainty that each year’s young grass will be devoured by caterpillars and that more or less grass of the second and third years’ crops will be similarly destroyed. For some reason, unknown to me, the caterpillars as a rule do less and less harm as the grass increases age, though in some seasons they take everything – old and young. The first year in which I could have attempted to save seed with any probability of success was in 1891, but I should then have had to shut up a paddock difficult to spare; as the season turned out it was fortunate that I didn’t make the attempt for the caterpillars were so numerous that they devastated nearly all the grass saved for seed, and seed was so scarce that I had to send to New Zealand for supplies”.

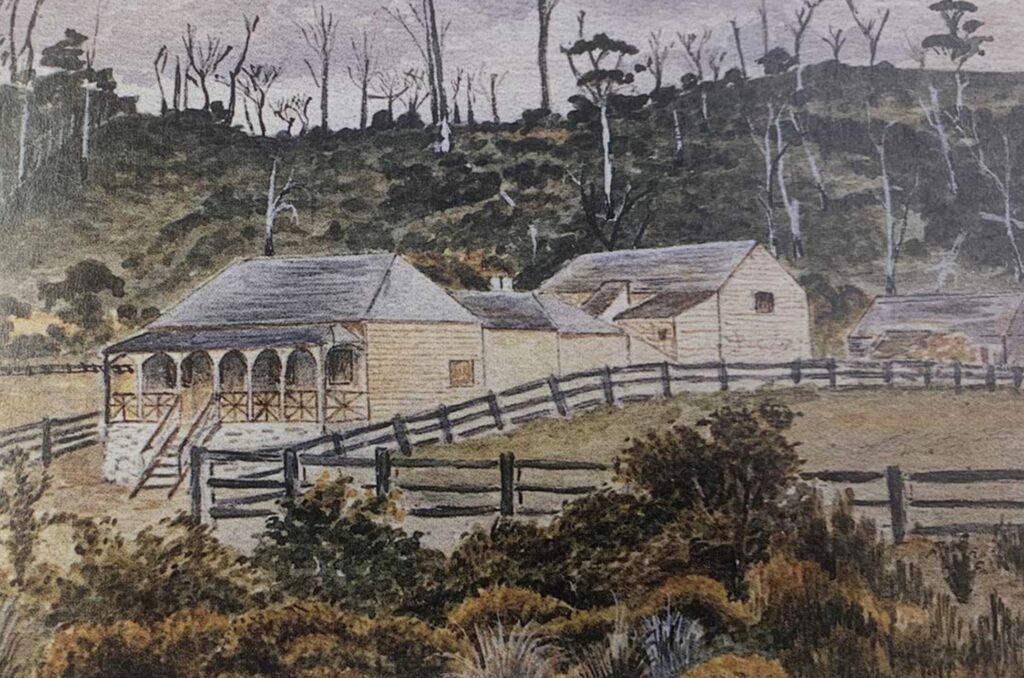

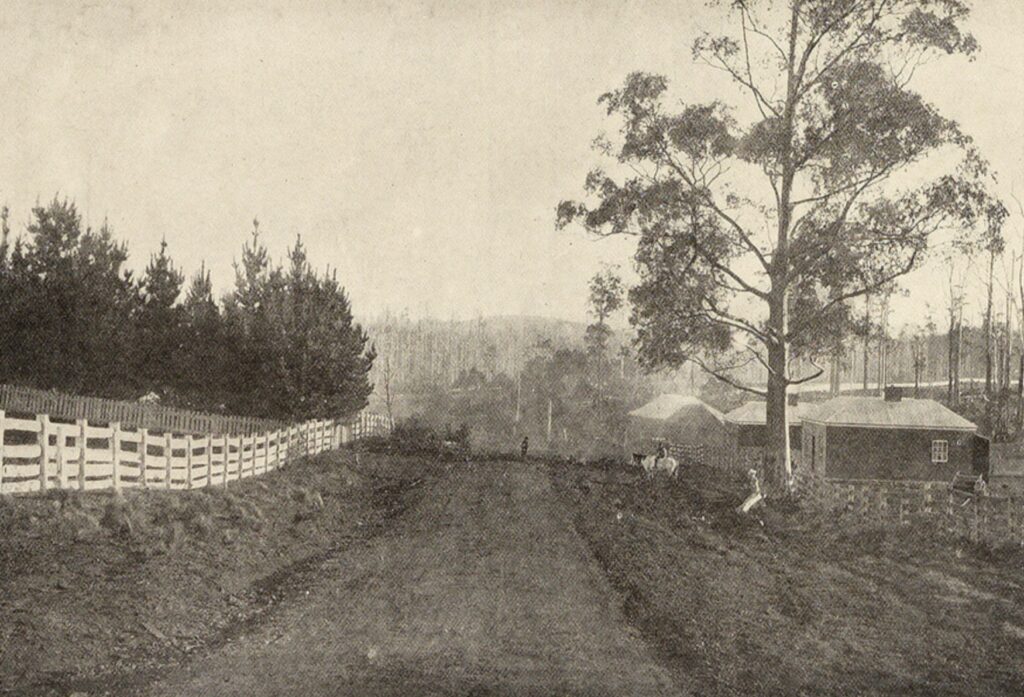

Under the guidance of the new Chief Agent, Andrew Kidd McGaw, the VDL Co. set up a sawmill in Burnie to cut timber for the London market and lower grade timber for the local market. The rainforests in the Ringwood Estate supplied the timber for the sawmill. In 1908, a subsidiary company was established to run a separate timber business.

There was no thought to regenerating the forests after harvesting. Instead, the focus was on scrubbing and clearing the residual trees and debris, burning and sowing to improved pasture. But just as they experienced caterpillar problems closer to the coast, they also faced similar problems on Ringwood. McGaw vented his frustration in March 1907:

“Caterpillars have entirely destroyed the grass in the paddock at the 27 Mile necessitating the feeding of the draught bullocks entirely on chaff. This is proving rather expensive, and I have therefore brought the bullocks down for a rest at Ridgley”.

However, a couple of years later, McGaw reported the first summer that the caterpillars had not:

“…eaten every blade of grass just as we were ready to turn cattle on the grass”.

In January 1910, McGaw inspected the Ringwood estate and found:

“…the caterpillars, which have been very prevalent this year, had got into patches of the [26 Mile] paddock. On that day very little damage had been done, but I hear to-day from the man in charge that they have played very serious havoc with the grass and that we shall only be able to reap patches”.

He also reported on the severe effects of the caterpillars that summer, including outside VDL Co. land:

“The caterpillars have done an immense amount of damage to the earlier grassed lands this season. Hardly a single section from the 14 mile up to the 27 Mile has escaped. When I was at Hampshire the previous week, I learned there that the caterpillars had cleared out every run that had been shut up for seed. There is absolutely no help for it. In rough bush country nothing can be done to stop the pest. In many of the districts along the coast near the sea, very considerable damage has been done to the cereal crops”.

Owing to the “ravages of the caterpillars”, McGaw said they only obtained 20 bushels of grass seed from the 26 Mile paddock in March 1910 instead of the 200 bushels he expected to reap that year. Later that year, McGaw saw signs that the caterpillars may attack again, and he sent up another 100 head of cattle to eat down the surplus feed. He kept the old bullock paddock at the 27-Mile as a reserve in case the caterpillars did severe damage claiming:

“Caterpillars do not as a rule do as much damage to old pasture as to new”.

The killing of the improved pasture on Ringwood and low beef prices reduced the profits considerably the following year. So McGaw decided to buy a small herd of about 80 well-bred dairy heifers while cattle prices were low. He did, however, believe Ringwood was admirably suitable for summer dairying.

It is not the first time a Chief Agent thought Surrey Hills was suitable for dairying. In 1839, Edward Curr first floated the idea. The Court of Directors, based in London, were very keen on his suggestion, especially after they read in the “Colonial newspapers” that butter was retailing in the “settled districts” at four shillings per pound. The 1840 Annual General Meeting discussed the potential of a dairy on a large scale to provide a profitable source of income.

Curr wrote in July 1840:

“No attempt has yet been made to establish a dairy in this district, chiefly because all the labour the Company commands is required for a large herd, and which even now are not so complete but that more and desirable, and partly because the cattle feeding over much an extent of country are not sufficiently tame and a dairy can only be attempted on any large scale with cattle which have been tamed and handled when they were calves”.

The following summer, however, a dairy on a moderate scale was established at Talbots Marsh, and the Court was pleased to hear:

“…that the cattle at the Hills are becoming tamer and more domesticated”.

The correspondence doesn’t refer to any further developments with the dairy. Therefore, I believe that the enterprise waned with the departure of Curr not long after, or it wasn’t established in the first place.

McGaw’s plans for a dairy were part of an experimental farm he established in 1913 about two miles from Guildford, adjoining the railway line. However, a year later, there was no mention of the farm again in the correspondence.

Caterpillar problems on VDL Co. land were not mentioned again until the end of 1933, during drought conditions, when the VDL Co. was leasing land for farming activities after their land holdings were sold to Gerald Mussen:

“Caterpillars have appeared in great numbers and are doing very serious damage over the whole North West Coast. Many oat crops are being harvested green to be used for hay. The destruction is however so sudden that large areas cannot be saved. The caterpillars have appeared at Ridgley in our grass which we can only save by knocking down with heavy stocking – a rather inconvenient expedient at this time of year. This pest has always been a worry, but we have not been troubled very much with it for several years. The caterpillar is known as the barley grub or army caterpillar. When attacking cultivated grains, or grasses which have been allowed to seed, the caterpillar makes the crop useless by climbing up the stalks and nipping off the ears of grain or grasses just below the head. In a few days they will completely strip a whole field. These grubs often travel in immense numbers in one general direction, and they are difficult to combat. In the case of the Woolnorth paddocks the caterpillars were bred in the paddocks and were not travelling”.

In the 1950s, the VDL Co. frequently understocked its pastures, leading to weed outbreaks. This was before insecticides such as DDT were available to control corbies and winter corbies and herbicides to control weeds. Bob Hardy recalls the blister scars he carried after using a heavy hoe in those days to cut the thistles out of his uncle’s pastures one by one!

Bob outlines a typical pattern associated with agricultural practices to combat the outbreaks of corbie, winter corbie and Oxycanus grass grub.

“Usually, improved pastures tended to be free of insect pest damage at least three years after sowing. In late summer/autumn of the first year, excessive pasture growth left a considerable layer of long-dead grass on the soil surface in February/March. It led to good flights of corbie or winter corbie. Then in spring, a large population of caterpillars feed on the leaves of pasture grasses, severely weakening the grasses. Next, the invasion of broad-leafed weeds, such as scotch thistle and wild radish, took over the area of denuded grass. The following summer/autumn, weeds would grow to waist height and overwhelm the pasture. In spring, the area was usually ploughed or cultivated in preparation for establishing a potato crop or maybe turnips to feed the stock. After another potato or turnip crop in the third year, the area was cultivated and sown with pasture seeds“.

The problems faced by the VDL Co. were in an era so foreign to us today before the availability of insecticides and herbicides. Dealing with the problem then was a bit more problematic and involved a lot of trial and error.

Newspapers reported a whole range of remedies from farmers. In 1847, one explained how he killed a dozen white grubs known to eat the root of pastures. After placing them in a saucer half-filled with water:

“…a teaspoonful of Guano had been put and well stirred. They immediately began to feel uneasy, and in about two hours the whole six were dead”.

In 1854, English ornithologist, malacologist, conchologist, entomologist and artist William John Swainson was invited to Tasmania to report on trees. While established botanists such as William Hooker and Joseph Maiden were scathing about Swainson’s botanical knowledge, he did enter the fray about dealing with the “extermination of the grass grub”. He suggested that when the larvae changed to the pupa or chrysalis state, the farmer should:

“…plough up the whole meadow which they may have partially destroyed. The chrysalis will be found at the bottom of the hole, in which it lived as a caterpillar. It then becomes inactive, torpid, and utterly incapable of seeking new quarters, if turned up by the plough or spade. Being a helpless, inactive lump, yet highly susceptible of the least change of temperature, it will inevitably die of itself, even without the least external injury. Thus everyone in a whole paddock may stand a good chance of being extirpated. The ground should then be knocked about or harrowed, and if sown again with other glasses than rye grass, I shall be much deceived if it is not covered, in the rainy season, with a fine clothing of young grass…”

Mr James Blenhorn from the Railton Board of Agriculture suggested a different approach in 1894:

“…I may say for the last eight or nine years I have been working amongst the farmers on the N.W. Coast, and advocating lime for the destruction of grubs, etc. I have proved it a sure remedy on several farms for the underground grass grub or greasy cutworm…”

In 1933, the President of the Moriarty Agricultural Bureau said he tried a remedy suggested by their Agricultural Organiser, Mr Fricke, to destroy the caterpillars when they appeared in grass paddocks:

“…a bushel of bran, two lb. of treacle and three 1b. of arsonate of lead (not being able to secure Paris green as recommended), and had spread it, after mixing it as dry as possible. The result was very satisfactory, large numbers of the caterpillars being destroyed”.

It seems wherever there is improved pasture or backyard lawns, there is likely to be a caterpillar problem. Next time you face the need to deal with an outbreak, why not stop and reflect on how you might have dealt with the issue before the availability of readily-available insecticides, just like the VDL Co. and other pastoralists had to.

Robert, you failed to mention that Caterpillars also became prevalent on Surrey Hills in more recent times. They were exotic and yellow all over.

True, I didn’t talk about those ones.

Do you think insecticides would make a difference?!

I remember an army of worms, similar to the southern army worm, going through the West Mooreville Road area, maybe 1960s. They were everywhere, all through the house as well as the property. They were messy when you squashed them!

My father diverted them from some of the paddocks by ploughing a furrow around the paddock, giving them a 100-150 mm vertical dirt wall to climb. The trick with the furrow was to get it the right way around so they had to climb the wall. While they could climb a stem of grass, they didn’t deal with climbing the vertical earth face so well.

It worked well as I recall. It reduced the amount of worms enough so the paddock survived.

Yes, I can remember severe infestations of southern army grubs and corbies when farming at West Ridgley.