Madigan’s Career at a Glance

Dr Cecil Thomas Madigan (1889-1947) studied and later taught Geology at the University of Adelaide. His thirst for exploration started in the Antarctic, working with the famous Sir Douglas Mawson. Madigan survived two polar winters and remained a commanding officer when Mawson failed to arrive in time for the ship ‘Aurora’ to collect them. On his return to Adelaide in 1914, he received the King’s Polar Medal for his contribution to Antarctic exploration. He later spent time in Sudan as a geologist and noted the vital role of camels in the desert.

The fiercely competitive Madigan was also motivated to match Mawson’s exploits and fame. To achieve this, he conducted studies into the parched interior and noted the so-called “Arunta” Desert as one of Australia’s last “untrodden”

areas.

Expedition Sponsor AA Simpson

This successful 1939 expedition received financial backing from Alfred Allan Simpson of the Royal Geographical Society, and the desert now bears his name. Mr Simpson also contributed generously to Madigan’s 1929 aerial survey of Central Australia. He helped finance Mawson’s Antarctic expeditions. He was unfortunately in poor health and passed away soon after Madigan returned from the desert crossing but did live long enough to see the film of the crossing.

Left: Alfred Allan Simpson.

State Library of South Australia [PRG 246/33/9]

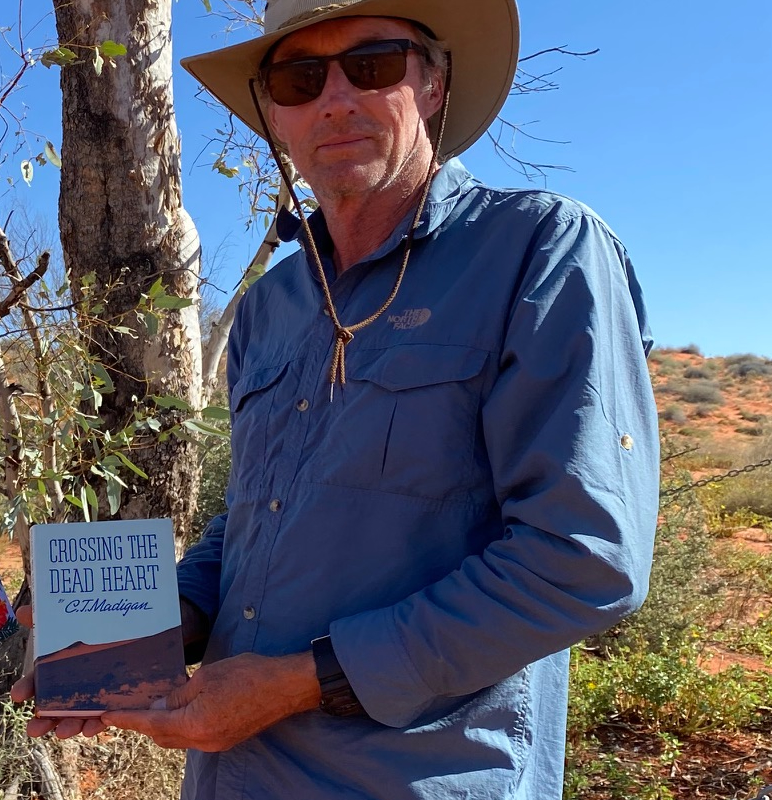

In 1945, aged 57, Madigan himself tragically died of heart failure. He had served his country courageously in both world wars. Cecil Madigan penned a book on his desert adventures, Crossing the Dead Heart, but did not live to see it in print.

Madigan’s Methodology

From 1929 and for the next ten years, Madigan studied the geology and geography of the Simpson Desert to mount a desert crossing if seasonal conditions became favourable.

His idea of a successful expedition was to return safely and leave nothing to chance. His stern words that “adventure is usually due to incompetence or invention” give insight into his pedantic attention to detail.

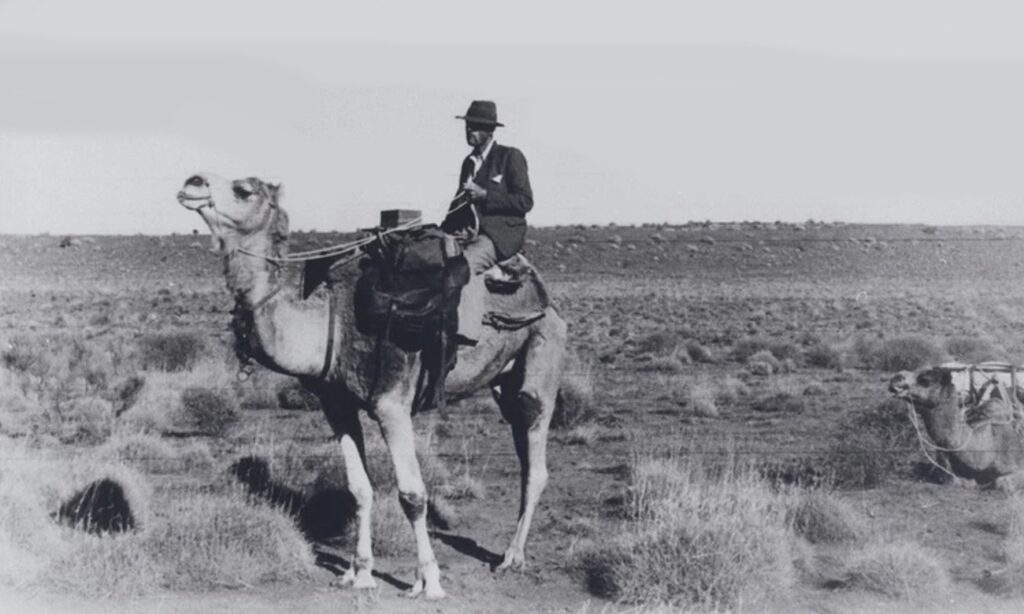

Madigan planned to use a team of 19 camels and nine men to cross the dry and dusty northern desert, timing the crossing with favourable rainfall in far west Queensland. He would travel approximately 25 kilometres per day across the “dead heart” to reach far west Queensland, where forage and water abounded.

Madigan conducted numerous aerial surveys around the Simpson before the trip to make a photographic record of the landscape. He generally found it a relentless succession of sand ridges interspersed with claypans and spinifex vegetation but no sign of water. Before the land crossing, another aerial reconnaissance was undertaken with Molly Clarke of Old Andado Station, a grazing outpost on the western fringe of the desert.

The expedition descending a sand ridge and heading east across the desert. Photo State Library of South Australia.

The Crossing

Madigan’s desert crossing commenced at Old Andado Station, about 330 kilometres south-east of Alice Springs. The homestead and stockyards lie nestled between two large sandhills. Although the land is inhospitable in the dry season, the underground water quality is exceptional.

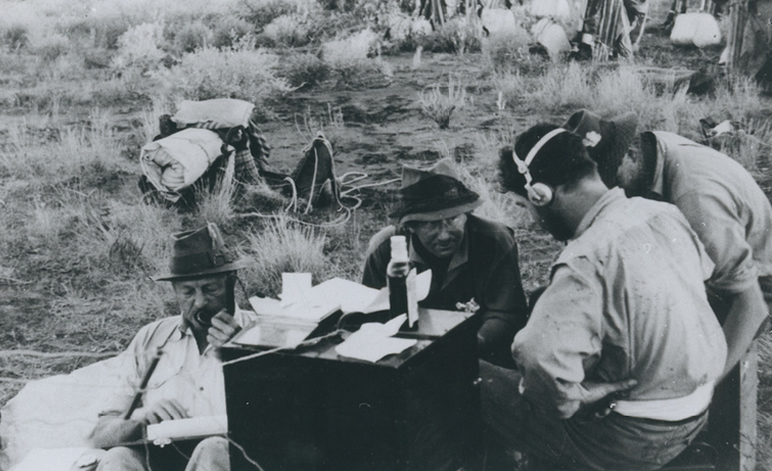

At this point, Madigan was accompanied by Tom Kruse, who later became the “Birdsville Mailman”. Tom assisted with transporting supplies and equipment to Andado, ready to be sorted and loaded onto the camels. The nine men who departed on the trip were Cecil Madigan as leader, Albert Hubbard as cook, wireless operator Robert Simpson, biologist Harold Fletcher, soil surveyor Robert Crocker and photographer David Marshall. The Afghan camel handlers were Jack Bejeh, Nurie, and an Aboriginal stockman called Andy.

Each team member had a specific task, and Cecil organised to report in with live transmissions from remote desert locations to ABC radio studios.

Madigan turned east at Camp 5 to keep their steady pace north to cross the Colson Track. This was previously named after local legend Ted Colson, who made a more southerly crossing to Birdsville with camels in May 1936.

As Madigan reached Camp 8, the men and camels crossed some 300 dunes, which had grown significantly, measuring up to 30 metres in height. Unfortunately, the party was held up by overnight rain, which continued into the next four days, quite a phenomenon in the desert.

The rain delay spent at Camp 8 had diminished the camp’s stores more quickly than anticipated. Adding to that, the camels still had no access to substantial feed, and the increasing size of the dunes was very wearing on the heavily laden camels.

Approaching Camp 10, the lack of feed was becoming a genuine concern. The rains in Queensland had not reached this far west, and the camels were struggling to make a reasonable distance each day. The dunes were now bigger than ever, and a couple of camels struggled. They had crossed over 40 giant sand ridges but only covered 17 kilometres in the day. The party was not even halfway to Birdsville, and no feed was in sight.

The success of the expedition was now on a knife-edge. Jack the cameleer suggested releasing the worst camels and redistributing the load. Those camels could follow as they wished. Spirits were at a low ebb as Madigan retired for the night, thinking, “feed can’t be far away now”.

The following morning the camels were reloaded, and the expedition set off. No doubt they wondered what would the day hold in store? After crossing only two dunes, the valley below opened up to some excellent “munyeroo” or pigweed that the camels devoured. Only 15 minutes since departure, the camels were quickly unloaded again and rested for the day at Camp 11 to feed. Spirits soared as failure was averted and success now seemed within reach.

Heading east, Madigan reached the Hay River at Camp 15. He followed the river bed for one day to the south, where he blazed his initials on a gum tree (M39), now known as the Madigan Blaze Tree. It is located at Camp 16 on the Hay River Track, which bisects the desert in a north/south direction.

The Queensland-Northern Territory border was crossed just after Camp 17, and by Camp 20 the expedition had reached the catchment of the Mulligan River and Eyre Creek. The expedition crossed the last sand hills and entered Birdsville at 4 pm on 6 July 1939, 32 days after departing Old Andado Station.

Only 5 days after reaching Birdsville, Madigan headed south to Maree via the shores of Lake Eyre. Photo State Library of South Australia.

Only 5 days after reaching Birdsville, Madigan headed south to Maree via the shores of Lake Eyre. Photo State Library of South Australia.

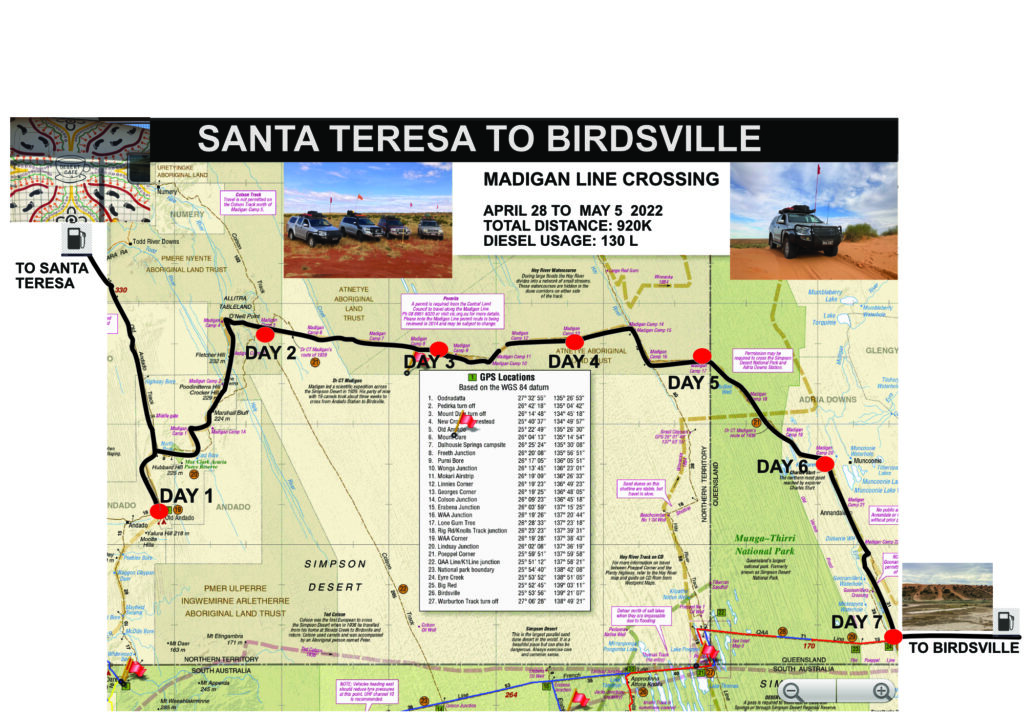

The Madigan Line in 2022

The Queensland section of the Simpson has now been renamed “Munga-Thirri”, which translates to Sandhill Country. It is a reminder that local Aboriginal people regularly moved in and out of the desert as seasonal conditions permitted.

The Madigan Line remains an iconic destination and unforgettable experience for many modern-day adventurers into the Simpson desert. It’s all about the journey, not to mention the destination of Camp 25, the legendary Birdsville pub.

Crossing a majestic dune in the eastern desert. Photo Janine Waters.

Crossing a majestic dune in the eastern desert. Photo Janine Waters.On a recent trip in April/May 2022, our party of four vehicles reached Birdsville in 8 days. We camped at Old Andado, Camp 5, a claypan just beyond Camp 8, Camp 13, Camp 17 and Camp 20. Our last camp was near Eyre Creek on the QAA line. Again, the traffic was almost non-existent. The exception was at Camp 17 when we were passed by a commercial group of five vehicles making the trip in four days.

Like Madigan himself, we needed to prepare methodically and have sufficient fuel, food and water for ten days or more, to allow for breakdowns or adverse weather conditions. It is recommended to have a high clearance 4wd fitted out for remote travel. Our four vehicles used between 130 to 190 litres of diesel each.

The trip holds particular interest as all Madigan camps are now marked with yellow steel pickets. It breaks the journey up into mini-stages so one can visit three or four camps a day. Some camps at each end of the line are no longer accessible as they are on private land (Camps 23 and 24) or in areas of Aboriginal cultural significance (Camps 2 to 4). The final destination is Camp 25, which is opposite the Birdsville pub. The Madigan Line intersects both the Colson and Hay River Track, which can be used to connect the Madigan to the French Line and Plenty Highway, allowing access to both north and south.

A shady camp under Gidyee trees on the claypan at camp 17. Photo Janine Waters.

A shady camp under Gidyee trees on the claypan at camp 17. Photo Janine Waters.The Madigan expedition was the accomplishment of one man’s lifetime dream, which was achieved with military-style precision and planning. There was no less adventure with daily challenges and hardships in a remote and inhospitable environment. The track is now a fitting memorial to a modern-day explorer, his men and their visionary benefactor, Alfred Allan Simpson.

Convoy “crossing the dead heart “ and heading east past Camp 17 nearing the Qld NT border. Photo Peter Waters.

Convoy “crossing the dead heart “ and heading east past Camp 17 nearing the Qld NT border. Photo Peter Waters.You can enjoy this archival video filmed during Madigan’s expedition on You Tube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vS1Yu4PPo-M

With researchers like you Robert and writers like Janine and Peter, who needs a 4 wheel drive?

Thank you.

Very good, but a map would have enhanced the article.

John