The Great North Road was one of three great roads built simultaneously out of Sydney, heading north, west and south. While there is little evidence of the Great Western and Southern Roads, much more evidence still exists of the Great North Road. Up to 43 kilometres remain intact.

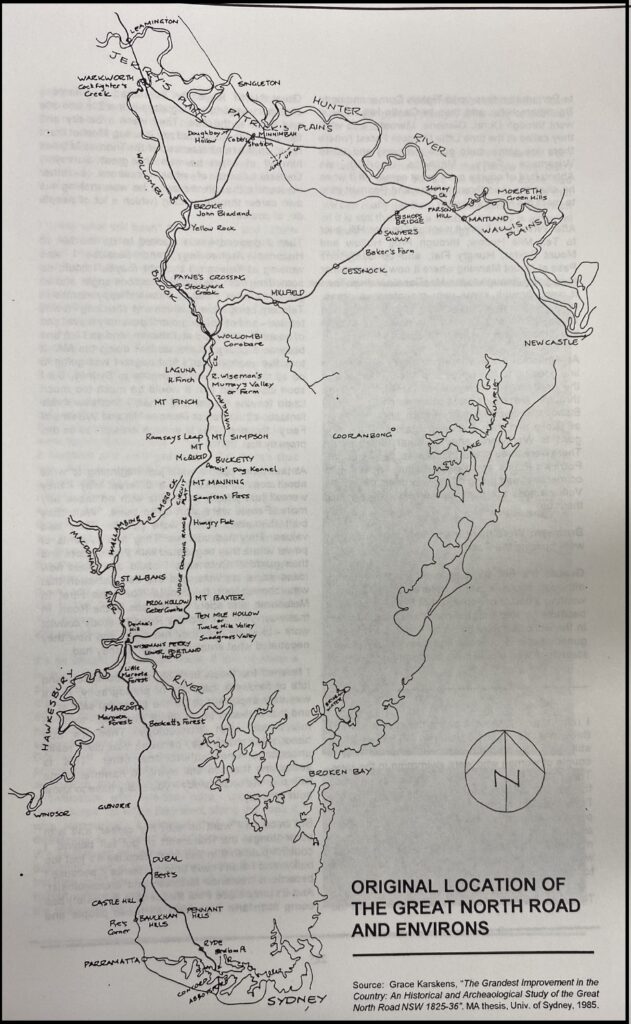

The Great North Road was built entirely by convict labour between 1826 and 1836. It ran between the present-day Castle Hill turn-off from the Windsor Road at Baulkham Hills, over some rugged terrain north to the Hunter Valley for 250 kilometres. As a Great Road, the intention was to serve the entire Hunter Valley, so it branched at both Wollombi and Broke to Maitland, Whittingham and Warkworth in the Upper Hunter.

While we spent some time on a house sit at Whittingham in the Hunter Valley a year ago, we saw first-hand remnants of the road at Wollombi, and its genesis is a remarkable story. Remarkable because the road never fulfilled its purpose after nearly a decade of building. It was immediately abandoned due to the isolation of the road and the advent of steamships. A paddle steamer made sea transport between Sydney and the Hunter Valley more efficient. Over time, other more hospitable and more direct routes were discovered and built. That meant both grand and modest structures on the Great North Road were left neglected.

As early as 1804, there had been a need in the colony for a separate place of punishment for convicts who had committed crimes since their arrival. Governor King chose the site of present-day Newcastle as a suitable place since it was, at that stage, sufficiently remote from the main settlement at Sydney to serve as a prison.

In addition, the only transport between Newcastle and Sydney was by water.

Governor Macquarie maintained the new penal settlement until late 1810 when its effectiveness as a prison began to dwindle. While initially settlement was not permitted on the lower Hunter, there were settlers at Jerrys Plains in the Upper Hunter by 1817. The first, more circuitous land route to get there from Sydney, which ran between Windsor and Jerrys Plains, was opened by 1819 and called the Bulga Road. However, it was never considered a suitable route for a permanent road because it was very rugged and didn’t access the Lower Hunter Valley. It is somewhat ironic, however, that after it was built, the Great North Road serviced the same areas the Bulga Road had reached in 1829.

Meanwhile, a problem soon started where convicts could travel up the Hunter Valley to Jerrys Plains and follow Bulga Road south and escape to Windsor. By 1825, the bulk of alluvial and more attractive land along the Hunter River and its tributaries had been taken up by settlers. Both these problems led Macquarie to move the convict prison from Newcastle to a new and remote settlement at Port Macquarie. “The extensive plains of rich and fertile land…now become an object of valuable consideration in the necessary increase in population”, he wrote.

The increase in settlement farther and farther away from the main centre of Sydney meant the need for better and more durable roads to newly settled areas such as the Hunter Valley. More importantly, it also meant a reliable route for transporting stock and goods to markets in Sydney. But if the colony was to thrive and grow, it needed better planned and permanent roads “as good as any in England”. So, the major roads which began north, south and west of Sydney became Great Roads like their counterparts in England.

The speed with which the Hunter Valley was settled made the government aware of the urgent need for a road from Sydney. There were repeated efforts to locate a suitable access line between the two areas. There was a fear that the very rugged and challenging terrain separating the two areas would end up being the same as the earlier colonists faced when they were hemmed in by the ridges and gorges of the Blue Mountains.

In September 1825, a hastily selected and windy line was traced by Heneage Finch following his earlier survey that year. However, it is believed that he followed a line discovered earlier by Richard Wiseman over the ridges from Wiseman’s Ferry to Maitland. Finch chose a more direct towards agricultural communities in the Lower Hunter at Newcastle and Maitland, which meant his survey traversed the Wollombi Valley. Nonetheless, nothing immediately happened from his work.

The Hunter Valley settlers were described as “men of substance and standing” with capital and patronage that gave them influence in government matters. In April 1826, they sent a petition to Sydney calling for a good road connecting Sydney and the Hunter Valley. They pointed out that a survey for its location had already been carried out.

Governor Darling had, by this time, used the more recalcitrant of the ever-increasing numbers of convicts to build roads. To facilitate this, he developed the convict road gang system and established the Roads and Bridges Department to service them. William Dumaresq, the surveyor with the new department and the Surveyor-General, John Oxley, marked a roadline to Wiseman’s Ferry in May 1826. Two convict gangs totalling 67 men, were sent to Castle Hill North to begin on the road later that year.

The whole of the Great North Road demonstrates the hardships the convicts experienced. Convicts were required to build various forms of accommodation for themselves and their supervisors along the route. Initially, the convicts were housed in very rough huts. But later, every five kilometres, brick stockades were built by the convicts where they could sleep and eat, sometimes in freezing conditions with only one blanket.

In summer, the temperatures could get to 40 degrees, their rations were meagre, and all they had was a shirt and a pair of trousers. They were also allowed to wash in the creek or river once a week.

By the mid-1820s, the economy of materials used in earlier roads gave way to grand and elaborate structures. This followed a road-building revolution in England in the early nineteenth century. The rise of roading engineers such as John Metcalfe, Thomas Telford and John Loudon MacAdam turned old, crooked horse tracks into properly formed roads.

Roads were now properly surfaced and “trimmed” according to the latest technology, rather than being simple bush tracks formed by the wheels of horse buggies. Assistant Surveyor Percy Simpson began his construction period of the Great North Road according to MacAdam’s principles in 1828. Rather than an unplanned haphazard development, road construction became a science.

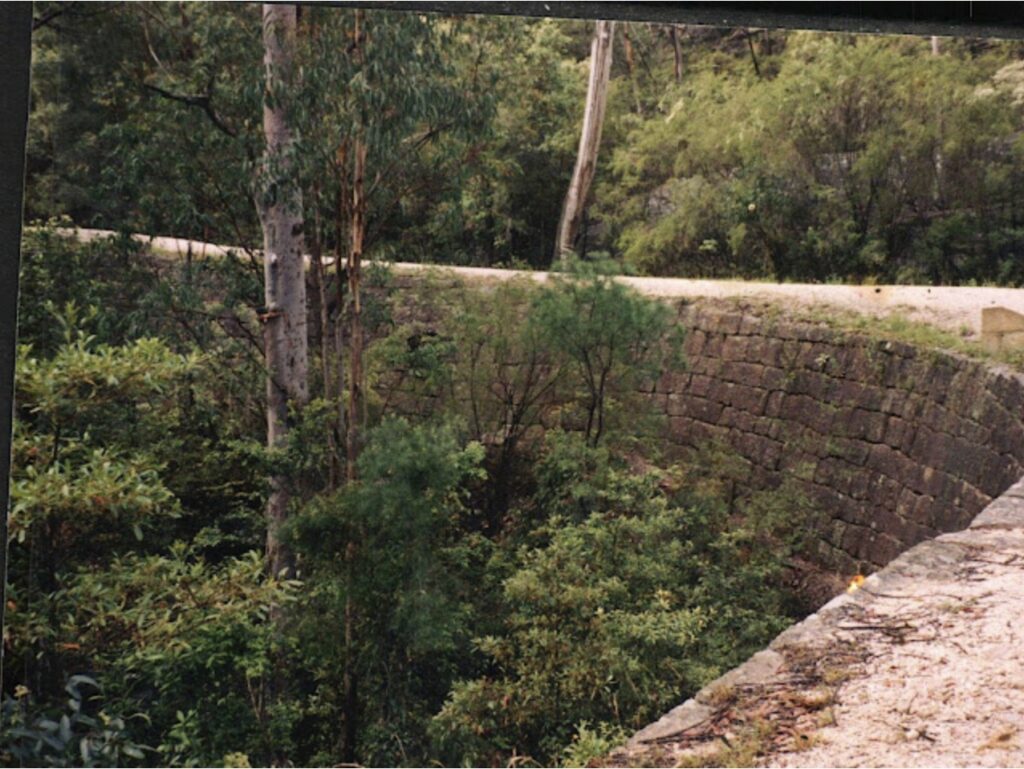

The convicts were involved in spreading gravel to form a hard surface and building retaining walls of stone to support the road. A great example is just north of Wiseman’s Ferry, where the road scaled a sheer mountain face and contained heavily buttressed retaining walls over nine metres tall. They also strategically constructed side drains and culverts to drain the road and blasted and cut rocks in steep sections to ensure the required grade was obtained.

There is no doubt the new road technology quickly adopted in New South Wales was due to the ready availability of convict labour. However, the use of convict labour for road building was not solely because of Darling’s ambitions for colonial roads. Nor was it not merely a convenient means for the Governor to build roads cheaply. Although, it could be argued that the convict road gang system was a way of providing public wealth because it offered the free settlers a means of access to rich unsettled lands.

The reality was due to a different set of circumstances. The period 1815-35 followed the end of Britain’s involvement in the Napoleonic Wars and was the period of large-scale convict transportation to New South Wales. The problem of finding employment for the thousands of convicts could not be solved by assigning them to free settlers, nor by sending the “second offence” convicts to Port Macquarie because the numbers were too great. Convict road gangs were a convenient use of surplus labour.

To get a perspective of the difficulty of building a road north, a drive on the present freeway between Sydney and Newcastle, blasted through the sandstone rock, provides a real perspective of the undertaking. In the late 1820s, without heavy machinery, it was no easy endeavour to build a good quality road, and it is no wonder it took a decade to build.

Finch’s original climb of the north escarpment of the Hawkesbury River, which followed Wiseman’s line, was abandoned early in 1829 before that part of the road was completed. Governor Darling disapproved of the narrow and precarious section, with tight corners which made it very difficult to traverse in a carriage. It was a steep section that climbed quickly above the valley.

When Major Mitchell took over the planned construction of the road, he was very meticulous in his approach, condemning the “old informal” methods. He insisted on shortening and removing obstacles which led to new routes for the road. The difficulty was that the new locations demanded by Mitchell were not traversable in their natural state and required burdensome construction work to remove materials.

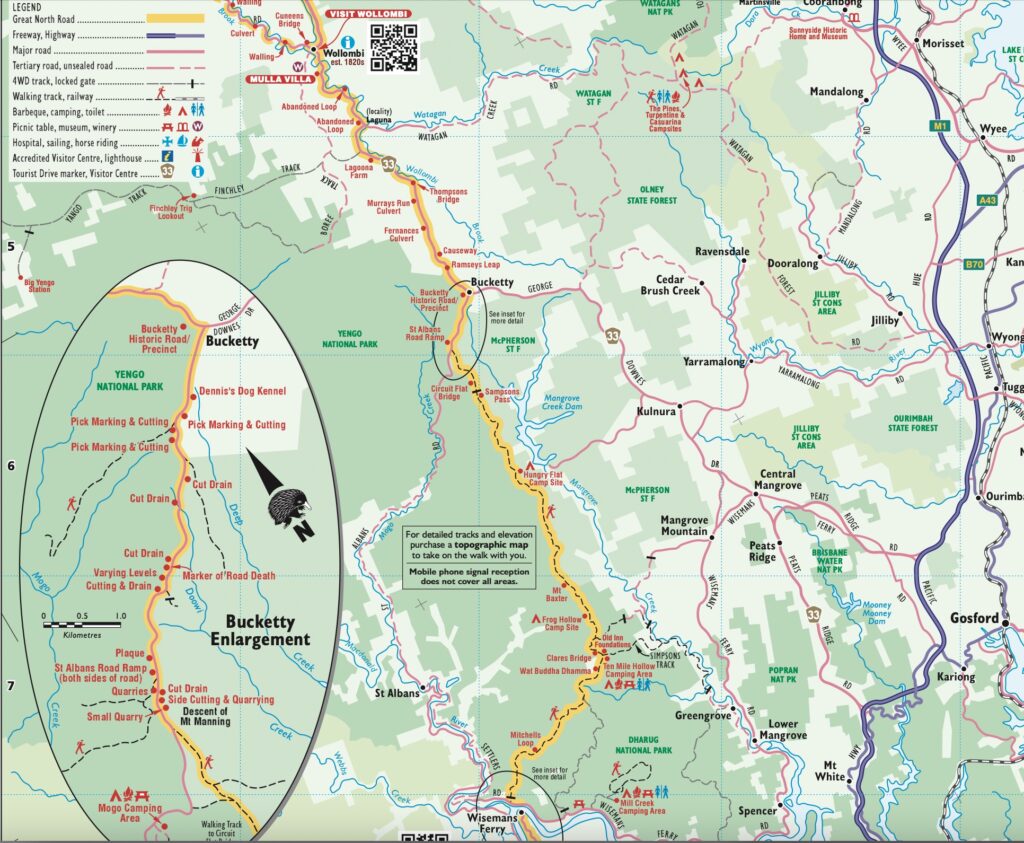

One passion Mitchell had was for a perfect, straight line, or rectilinearity, between destinations necessitating more earthworks for bench cuts and fills. He created much additional work over Mt Baxter, Sampson’s Pass, Mt Manning, Mt McQuoid, Mt Simpson and Mt Finch. Mitchell also selected a new, much shorter line for Finch’s Hill which became known as Devines Hill.

Unfortunately, not being an engineer himself, he overlooked the problem he created by believing straightness equalled symmetry of the perfect line. So while his roads may have been straight, they were not direct regarding traveller’s destinations. Consequently, the road avoided some major settlements such as Singleton, and a new branch road had to be subsequently built. The other problem was that his insistence on building his way made previously constructed sections redundant.

Mitchell’s endeavour, however, did lead to several impressive engineering feats associated with the road. For example, a 1.8-kilometre spectacular and intact section of the road is known as Devines Hill.

It is here where quarrying and masonry of the buttressed retaining walls nearly ten metres in height and a drainage system are very impressive. The blocks in the walls are carved perfectly to eliminate the need for mortar. There are also stone culverts built to drain the water off the surface of the road. It’s a testament to the stonemasonry skills of the time. Each sandstone block dug out of quarries weighed around 650 pounds or just under 300 kilograms. There is also evidence of triangular-shaped jumper bar marks and pick marks where the convicts quarried the rocks and shaped the stone blocks that form the retaining walls.

Hangmans Rock has a hole in the top of the rock, supposedly where offending convicts were hanged. Still, given the steps carved into the sandstone, leading to a shaded underside, it is more likely a place where the overseers could comfortably sit while watching the detailed work on the road below.

The bridge at Wollombi, now called Cunneens Bridge, was first erected in 1833 as part of the Great North Road crossing of Wollombi Brook. It was washed away in 1857 and replaced by another timber bridge. But it too was severely damaged in the 1893 flood. A new timber beam bridge was built in 1896. While that bridge has been replaced in time by a concrete bridge in 2011, remnants of the 1896 bridge remain.

The old Great North Road illustrates the success of the New South Wales penal colony and is associated with the large-scale introduction of transportation by the major European powers in the modern era. Because of this it is much more than just a road. It was built when the colony transitioned from a penal one to a free-market colonial settlement. It now deservedly forms part of the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property.

The short section north of Wiseman’s Ferry is open to for a scenic bushwalking’s and an opportunity to learn more about our convict past.

My family history at the Wollombi started with Thomas Matthews, a convict in chains who worked on the Great North Road from Coal River (Newcastle) to Wollombi Village, arriving 2 years before the Sydney GNR. It passed through East Maitland, but there is little information about its exact route to Wollombi. Possibly now the Old Nth Road through Sawyers Gully to Cessnock?

Apparently, these convicts were known as the ‘Double Distilled’ as they were troublesome in Sydney. Thomas married a young Irish free woman at Wollombi St Johns Church after the road reached Wollombi 2 years before the Sydney GNR. This was due to Caroline Chisholm’s questionable efforts to marry young, free, newly arrived women off the sailing ships onto the ‘packets’ to Morpeth, sailing up the Hunter River to her Immigration Barracks at East Maitland.