Introduction

The first telegraph message in the world was sent on 24 May 1844, using Morse code, a system of dots and dashes representing letters of the alphabet. The system was invented by Samuel Morse, inspired by the fact that when his wife died in 1825, he did not hear of the event until days after her funeral due to the slowness of communications at the time. The sender would submit a written telegram to a post office, where it was sent and translated into Morse code to the destination. The telegrams received would usually then be hand-delivered to the addressee. The sender abbreviated the words to reduce the expense of sending the messages.

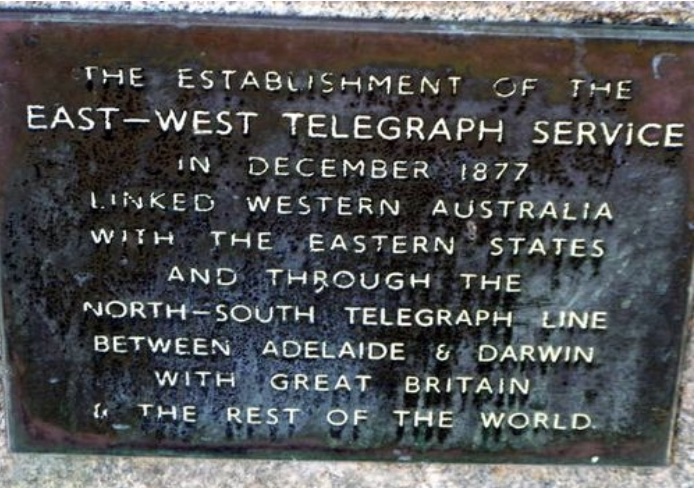

The first telegraph line in Australia was constructed in 1854 between Melbourne and the Victorian port of Williamstown. By the end of the 1850s, the capital cities in the eastern states, from Brisbane to Adelaide, were all connected by a telegraph line. Telegraphy was the primary form of distant communication for the remainder of the 19th century.

Western Australia was slow to utilise the new technology mainly due to the long distances required to connect the state with the rest of the country. The Western Australian and South Australian governments started discussions in 1860 to connect both states via a telegraph line. Nothing happened. Instead, Western Australia began establishing its own telegraph lines.

The first telegraph line in Western Australia was erected between Fremantle and Perth in 1869 by the privately owned Western Australian Telegraph Company. In 1870, a second company, the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph (EMT) Company, arranged with the government to establish telegraph lines south to Albany and Bunbury, and east to York, through Guildford, Toodyay and Northam. The EMT Company acquired the Western Australian Telegraph Company in 1871.

The Post Office Department renamed Post and Telegraph Department, supplied staff and buildings on the EMT Company constructed lines. The Guildford telegraph station was opened on 23 December 1871, and the rest of the stations followed, with the last, Albany, opening a year later, on 28 December 1872. On 1 January 1873, the government bought out the EMT Company and became the sole operator of the Colony’s telegraph system.

Meanwhile, the South Australian government put all its resources into building the Overland Telegraph Line to Darwin to link Australia to the rest of the world by joining the undersea telegraph cable, which had been laid from Britain to Java some years earlier.

The Overland Telegraph Line was completed in 1872, and the eastern state’s capital cities, already connected by telegraph, were then linked with the rest of the world.

The Western Australian colony was first formed to prevent colonisation by the French on the continent’s western shores. It became the first port of call for ships sailing from England and the last for ships leaving the east coast. The opening of the Overland Telegraph Line meant it suddenly lost its advantage of receiving news from England first. It would receive no current information and had to wait weeks, if not months, for any news because of the lack of telegraphic facilities. This was becoming of concern in business circles as the benefits of the telegraph system became apparent.

Plans for a Trans-Australia Telegraph Line

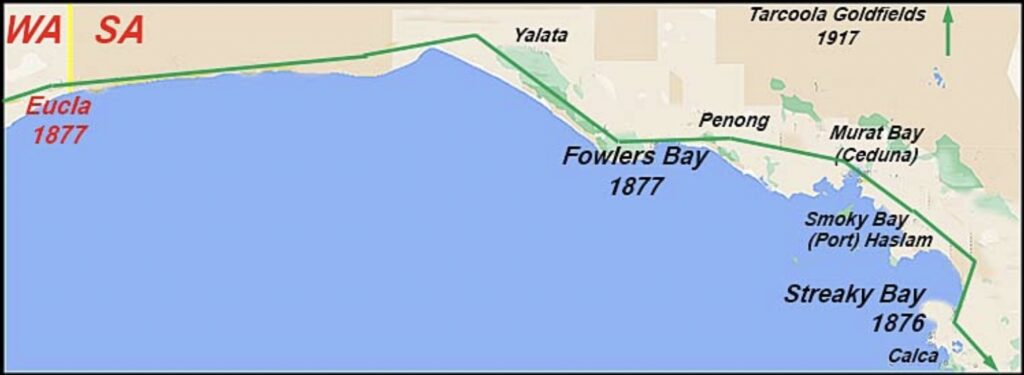

Western Australia and South Australia finally agreed to build a connecting line following the route explorer Eyre took along the coast across the Nullarbor Plain. However, it was November 1874 before the South Australian legislature authorised the expenditure to Eucla, which had been chosen as the natural connecting point closest to their border because it had the only sea landing place for hundreds of miles.

On New Year’s Day in 1875, Governor Weld erected the first telegraph pole in Albany, which would carry the telegraph to Eucla, thus connecting Western Australia with the rest of the continent and via Darwin to the rest of the world. It was a considerable feat for the newly formed Western Australian government.

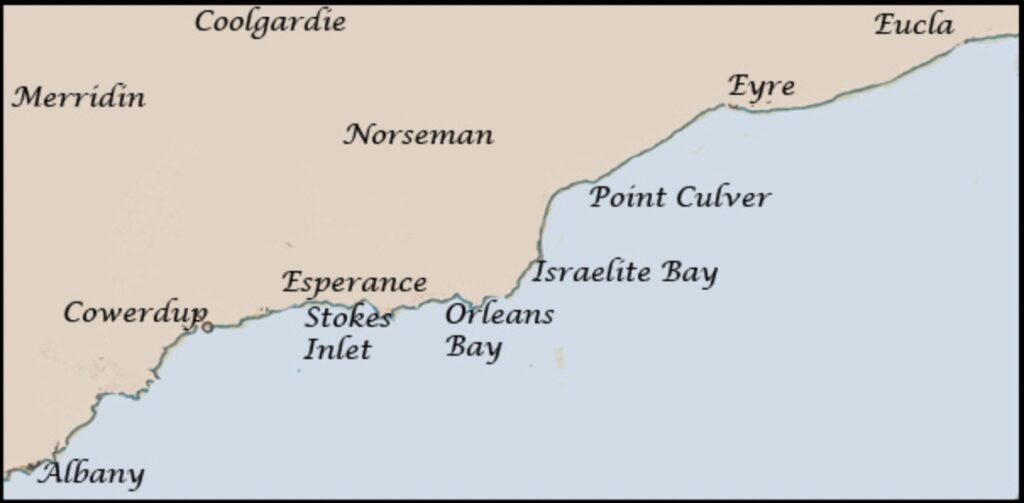

Because of the soft iron wire used for the line, which had poor conductivity characteristics, and the great distances and detrimental effect on the signal of the ocean mists, the line required repeater stations along the route, where operators would manually boost the messages in transit. Stations were opened at Bremer Bay (8 March 1876), Esperance Bay (8 September 1876), Israelite Bay (5 December 1876) and Eyre’s Sand Patch (17 July 1877). South Australia also constructed four repeater stations along the length of its line at Port Augusta (25 August 1875), Port Lincoln (1 March 1876), Streaky Bay (24 November 1876) and Fowlers Bay (1 May 1877).

The line quickly reached Esperance from Albany, but progress beyond there was slow. Plans to build the next station at Point Culver were scrapped as the site was considered unsuitable, and the safer harbour at Israelite Bay was chosen instead. Materials were transported to Israelite Bay using the schooner Mary Ann. In July 1876, the Mary Ann was anchored close to Israelite Bay during one of these trips. After a strong wind blew up overnight, the Mary Ann was wrecked on Bellinger Island. Fortunately, the crew and cargo were all saved.

The line followed the coast, and materials were transported by sea. Landing was difficult due to the cliffs and rough seas of the Great Australian Bight. The telegraph poles were lashed together and floated ashore, while the wire, other materials, and food and water for the construction teams had to be landed. The country was largely barren and dry, with no permanent water for hundreds of miles. Portable condensers mounted on carts placed in the sea were in constant use in some sections.

The Trans-Australia Telegraph line reached Eucla on 8 December 1877 and was opened the following day, the South Australian section having been opened to Eucla since August 1877.

The length of the line from Albany to Eucla was 1,207 kilometres, and from Adelaide to Eucla, it was 1,221 kilometres. There were 18,300 jarrah timber poles, 100 mm-square, spaced at 14 per kilometre in the West Australian section, and 12,474 iron poles spaced at 10 per kilometre in the South Australian section.

The early telegraph station buildings were erected as each place was reached. They consisted of tiny weatherboard houses of four rooms, each 11 feet by 9 feet, around a central passage. Cooking and washing were done outside in bush shelters. The Eucla telegraph station was twice the size of the buildings at the other stations as it had to house the staff of both the Western Australian and South Australian offices, which made it unique in its operation.

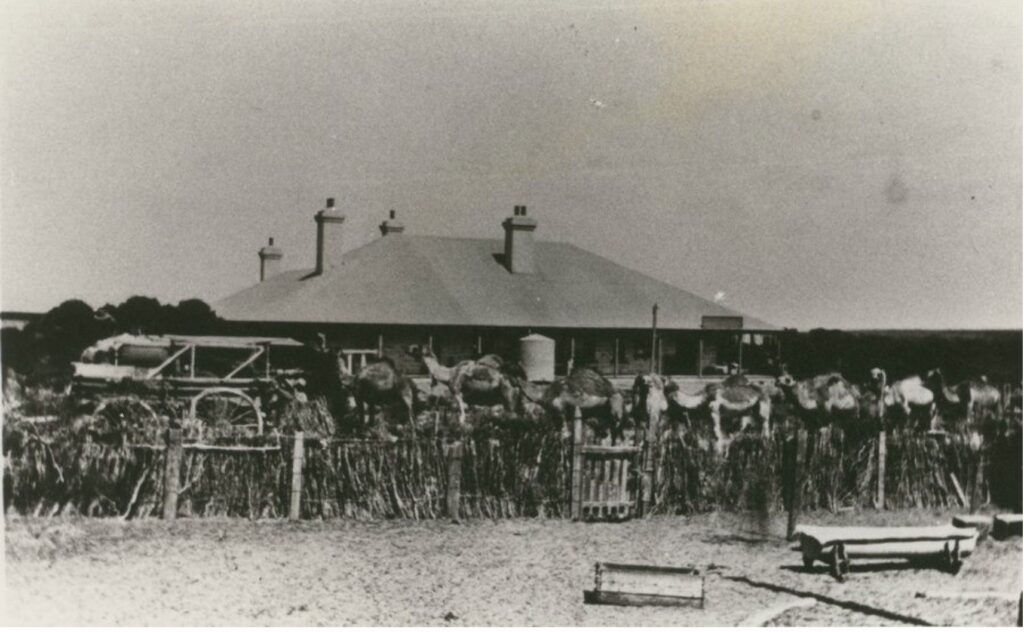

Linemen were employed to maintain the telegraph wire, with an Aboriginal assistant in the early years. The linemen were stationed at each telegraph station and patrolled halfway to the next station on each side. In 1876, the Postmaster General had authorised the provision of small, prefabricated huts of “galvanised sheet on a wood frame” to be erected along the line for the linemen’s use where tools, stores and rations could be kept. In addition, linemen were provided with camels and bicycles for travelling. To provide water for the linemen between Israelite Bay and Eucla, catchment sheds with tanks were established at several points. Each catchment shed comprised an iron roof on an open timber frame and was used by the linemen for shelter.

Bremer Bay Station

The decision to locate the telegraph station at Bremer Bay instead of West Mount Barren, as first planned, attracted the first European settlers.

The line to Bremer Bay telegraph station was completed by October 1875, and the original station had a shingle roof. The chimney and verandas were added later. However, it was not formally opened for traffic until March 1876 due to the question of the number of people required to operate the stations.

The finally agreed number was a station master, an assistant, a linesman and a labourer for fieldwork. Miss Mary Wallstead, daughter of pioneer settler John Wellstead, was the operator until the appointment of the station master at the end of 1877.

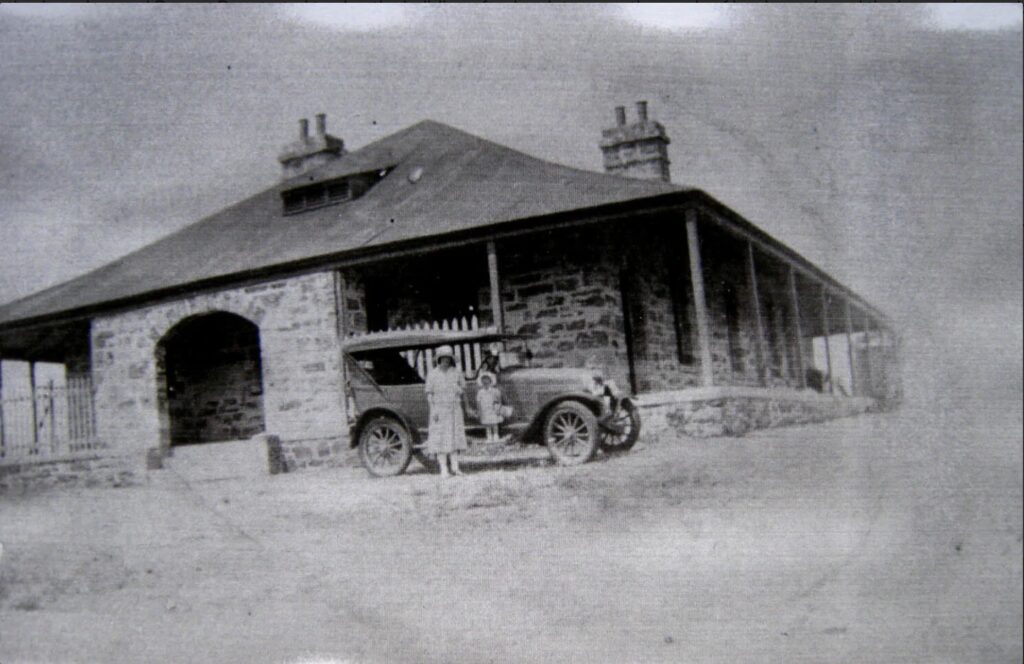

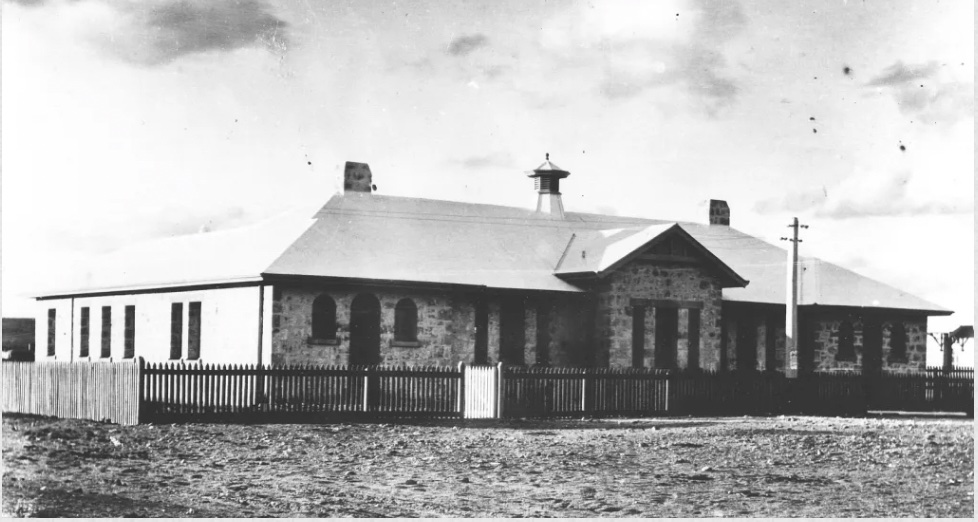

The original station building burnt down, and a new telegraph station at Bremer Bay was erected in 1896, just next to the first one. This time the local stone was used, and the building became a well-known landmark with colourful walls.

Esperance Station

On 8 September 1876, the line to Esperance was completed, and the Esperance telegraph station was officially opened for telegraphic traffic. The following month, the first Station Master arrived to take charge of the Telegraph Station – fifteen-year-old George Stevens.

Israelite Bay Station

Located 201 km to the east of Esperance is Israelite Bay. The telegraph station operated until 1917. The original building was replaced by a standard stone building in 1896.

The current site includes the ruins of a cottage built in 1884 and two graveyards where telegraph operators and others who lived in the area were buried.

Eyre Station

The Eyre telegraph station is close to Eyre’s Sand Patch, where explorer John Eyre found water and rested for three weeks as part of his epic 3,200-kilometre overland journey across the Nullarbor in 1841.

A Telegraph Master staffed the first station building with one or more assistants in a very remote location. A more substantial one-storey structure replaced the original building in 1897. It was built of local limestone with a wide timber-framed verandah.

The station building was left to decay when the station closed.

It was restored by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (now Birds Australia) and re-established as the Eyre Bird Observatory.

Eucla Station

The Eucla telegraph station was officially opened on 9 December 1877 and was the largest station along the line. The telegraph line from the South Australian end to Eucla had been built using steel poles, which were much more durable, in contrast to the jarrah posts used by Western Australia for their section.

The telegraph station enhanced the importance of the town, which had already been established because it was the only place where a jetty could be built so boats could moor to unload goods for hundreds of kilometres. The Bunda Cliffs to the east are the longest stretch of uninterrupted cliff face in the world.

There was little telegraphic traffic on the east-west line initially, and the single wire, which could only carry one message each way, was sufficient for the time. In 1881, 17,188 messages were handled at Eucla, increasing to 24,586 in 1882.

The gold finds in Western Australia in the 1890s resulted in significantly increased telegraph traffic, requiring more staff and larger station buildings, which were added in 1898. In the mid-1890s, many of the operators at Eucla were living in tents, and the roof space of the station building was used for accommodation.

It was reputedly the busiest telegraph station in Australia for a time. Delays of up to a week were common as a backlog of messages developed at each station. As well as an improved telegraphic system, larger premises were required to accommodate expanded operations and staff numbers.

In the 1890s, a plague of rabbits on the coastal plain devastated the vegetation on the dunes at Eucla, causing huge drifts of sand to encroach on the town. The sand drifts had encroached on the buildings even before they were abandoned. After the townsite was abandoned when the telegraph line closed, the new town was rebuilt 4 kilometres north of the original site. Despite being half buried in the sand, the stone telegraph station building can still be visited today.

In 1898, the population of the town was 47. With the addition of a handful of itinerant kangaroo shooters and the occasional traveller and visiting pastoralist, the population of Eucla is estimated to have reached 70 at its peak.

The Eucla telegraph station is an important remnant of the largest station on the 1877 East-West Telegraph line linking Western Australia with the eastern states and overseas. It acted as the transfer point of telegraphic messages between South Australia and Western Australia from 1898 until 1907 when the operations were amalgamated under the Western Australian Post and Telegraph Department. Western Australian and South Australian personnel jointly operated it.

This was mainly because, in the pre-Federation days, Western Australia used the International Morse Code, while South Australia used the American Morse Code. This meant that the telegraph operators sat opposite each other, dressed in starched shirts, waistcoats, collars and ties, with a wall representing the border between the two colonies. Each message had to be decoded and passed through a pigeonhole in the border wall.

The demise of the original line

Because the line was generally installed within a few hundred metres from the coast and consisted of a single 8-gauge galvanised iron wire using an earth return, it soon became apparent that the hostile conditions of the coast played havoc with the reliability of the line, causing many breakdowns due to corrosion and salt deposits on the insulators.

When the eastern goldfields were discovered in the early 1890s, Coolgardie became a large telegraph post, and the line was extended to the newly discovered goldfields at Norseman (Dundas).

The telegraph line was soon extended eastwards to Balladonia, where a repeater station was constructed, and then across the country to Eyre. The line was kept inland, following the foot of the escarpment, through to Eucla, thereby withdrawing the line from the coast and improving reliability. Despite this, the Eyre – Israelite Bay – Albany line section was retained due to the need for telegraph traffic to these regions. The inland route was upgraded to copper wire and steel poles, providing greater reliability and improved communications.

In 1927, a new three-strand telegraph line was constructed along the route of the Trans-Australia Railway, and the telegraph stations were closed. However, the government no longer required the original trans-Australian telegraph line. It continued to be used and maintained by the army as a military backup system and then by the pastoral stations along their length for their private telephone service. The line was finally closed around 1970 after phones were put over to the microwave system.

Undoubtedly, by any standards, the construction of nearly 2,500 kilometres of the telegraph line from Port Augusta to Albany along a virtually unknown coastline, most of which experienced notoriously rough seas, was an epic undertaking. No survey was taken. Surveyors merely reconnoitred a few kilometres ahead of working parties.