I am very fortunate to have worked as a surveyor during incredible technological development and advances in this vocation. This blog is in two parts; part one will deal with my early years up to the mid-1980s, and then the second part will cover the changes in personnel and technology that occurred and how they influenced my time.

It all started back in 1973 when I joined Associated Forest Holdings (AFH) as a Forest Technician, working for Dick de Boer at Ridgley. I still remember my first day measuring a Continuous Forest Inventory (CFI) plot in a Pinus radiata plantation in SJ1 out at Tewkesbury with Geoff Dean and Rob Hanson. There were lots of blackberries, and we had difficulty seeing the tops of trees some 25m tall.

For the next three years, I spent most of my time working with Dick and Geoff, developing both pine and eucalypt plantations across the AFH properties in the northwest of Tassie. From measuring CFI plots, insect infestations, fertiliser trials, weed protection and standing timber assessments, the role was exciting and had plenty of variety and challenges. However, my fondest memories were of the people I worked with, Dick, Geoff, Rob, Flip Wyker and Dave De Little, just to name a few.

In 1976 the AFH Surveyor, Bruce Hodgetts, asked Dick if I could assist him with doing some road locations in the Parrawe area, part of the 1926 Concession. Little did I know then that this would turn into a 23-year partnership with Bruce and surveying.

Back then, running road lines consisted of plotting grade lines on paper contour maps and then going out into the bush and locating them using a clinometer and a lot of awareness of the country you were working in.

However, I never stopped marvelling at the ability of Bruce and the Roading Supervisor, Teena Bester, and later Morris (Mort) Bloom, to visualise how the road construction would fit into the topography. They knew that just marking a tree or hanging some flagging tape would be enough for the construction crew to be able to build the road. This knowledge is something that you can’t get from a textbook. Instead, it is learned through practical experience.

When we had finished the road location, Bruce asked Dick if I could transfer permanently as his assistant. Bruce must have seen something in me, as I was sure I was not all that good at being the front man when running the grade lines through the bush. I can still hear Bruce & Teena saying up, up, up, up, down, I can’t see you, shake your helmet, up, down, there! However, they were very patient people. Although, as a side note, the very first road line I was tasked with doing myself was “Weening Road”, their sense of humour was not lost on me, nor was their patience again, as it took more than three attempts to get it right.

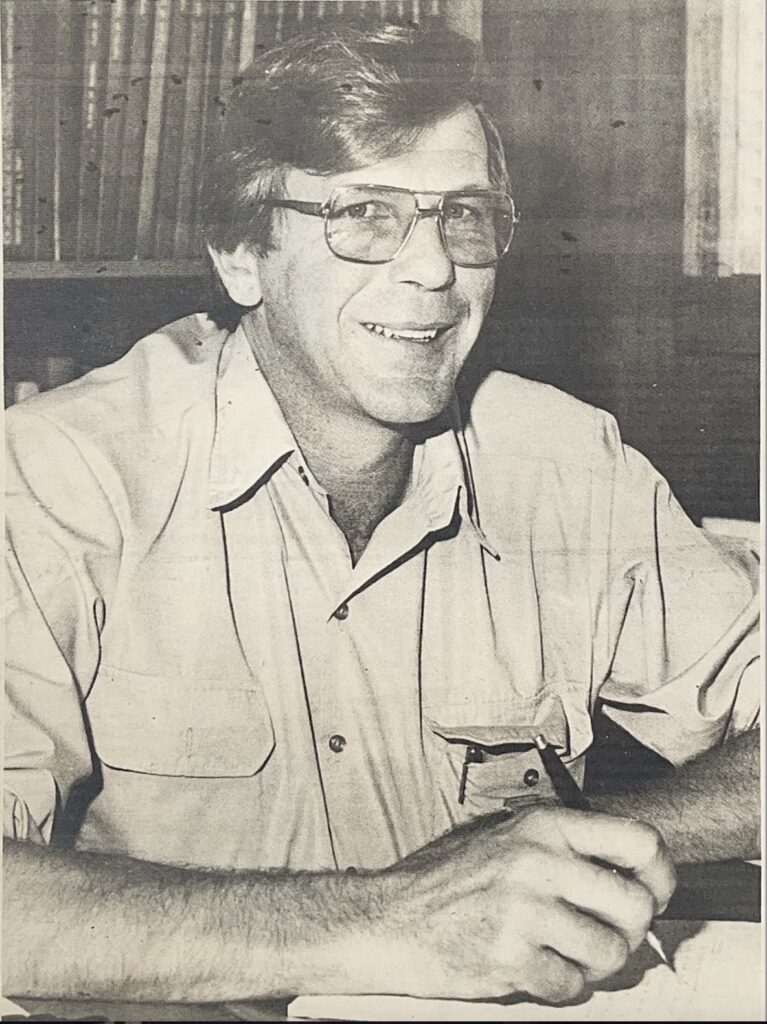

The surveying role at AFH involved much more than running road lines, and the 23 years I spent surveying the variety of roles and tasks made the job probably the best I have ever had. A lot of this was due to the people I worked with. I must make a special mention to Bruce Hodgetts. He was much more than a boss. He was a mentor, confidant, and great friend. I will be forever grateful for all the wisdom, guidance and knowledge Bruce gave me, thanks Bruce.

Pre the Electronic Age

Back when I started with Bruce, the methods used in surveying were very labour-intensive and required significant expertise in using the equipment, undertaking the task at hand, doing the calculations, plotting the surveys, and analysing the data.

To accurately run a property boundary required using a theodolite that weighed in the order of 20-25kgs, tripod, and steel surveyors’ 5 Chain with graduations in chains & links! Yes, this was before metric! Slash hooks, plum bobs, chaining arrows, half axes, spray paint (flagging tape was a later invention). We would fashion survey stakes out of pieces of dogwood, wattle, or any other species available. We would place the stakes along the boundary line using the theodolite, or if the theodolite wasn’t used, they would be eyed in utilising the plumb bob.

Just to explain the links and chain nomenclature:

- 100 links = 1 Chain

- 1 Chain = 22 yards (20.117m)

One very important lesson imparted to me was that you needed three stakes aligned before you could use them as a reference for placing the next stake. It was very easy to run a curved line when you were trying to run a straight line. I think there is still a line cut out in Parrawe that I did which wasn’t that straight! I did manage to pick up the error but not before the line had been cut out through some very thick horizontal scrub!

The process was to find a starting point. This required finding evidence from previous surveys using field notes from past surveyors, and sometimes this information was over 100 years old in the case of Van Diemen’s Land (VDL) properties even older. This part of the process was truly satisfying, as finding an old mark, corner peg or cairn of stones over 100 years old was very exciting to me. Measuring a distance required chaining in horizontal steps on the line set out with the theodolite, slashed, and cleared.

So, where you encountered sloping ground, you would have to go down or up in short steps, use the plum bob to mark the spot, put in a chaining arrow, and then move forward. Sometimes these step distances would be only 2-3 metres at a time, so measuring a boundary that was 500 metres or more could take several hours, sometimes days.

Working with Bruce on these jobs was great fun and very rewarding, although I am not sure Bruce thought so when one day, I cut the chain with my axe! Ever resourceful, a mending kit was carried in the car, so perhaps this may not have been such an unexpected occurrence.

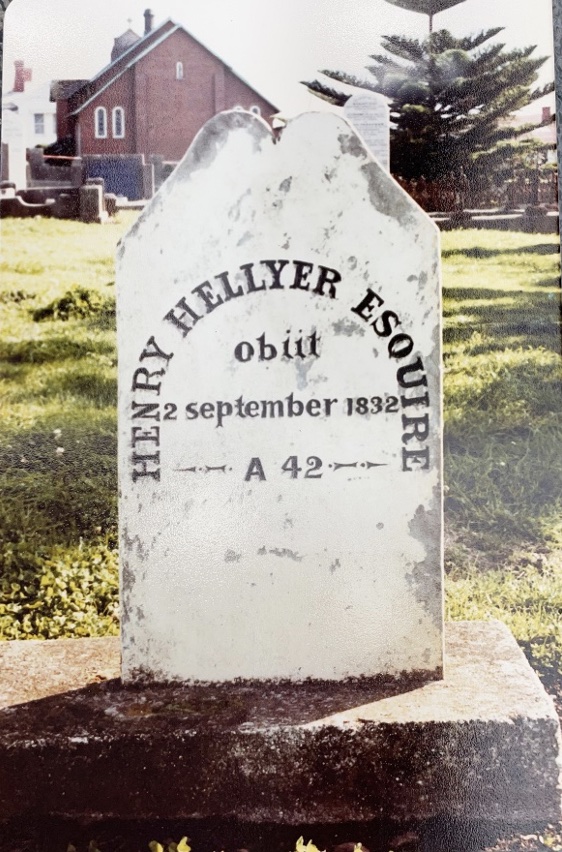

For me, and I know for Bruce as well, the greatest satisfaction we got with this was relocating parts of the Surrey Hills, Ringwood, and Woolnorth ex-VDL property boundaries. Retracing the steps of Henry Hellyer and Percy Sams’ surveys was a step back in time. When you came across the corners of these properties, particularly the one on St Valentines Peak, you could transport yourself back in time envisaging what it was like for them.

One of the most rewarding achievements in my time was to stand on the four corners of Surrey Hills and the two southern corners of the Ringwood blocks and traverse a fair proportion of the lines that joined them. You got a genuine appreciation of the enormous task Hellyer and Sams faced in doing this work. Some of the country is very steep, and the vegetation is thick plus, coupled with having to carry all your supplies, these men and their crews were some of the toughest pioneers Tasmania has seen.

Sometimes you have an experience in life where you think you have been somewhere before, but you know you haven’t. One such experience happened when I was searching through one of Sams’ survey field books of Surrey Hills from 1902. These field books were much more than just survey notes. They were a diary with each day’s work described. In one book, there was a reference to a new chainman. His name was Michael O’Shea! Unbelievable, to say the least; sometimes things just are too hard to explain. Seventy-five years earlier a person with the same name as mine was doing exactly what I was doing! I hope these field books have been kept as they are a wonderful record of life as a surveyor in the early 1900s.

Another task we had to do was undertake stockpile surveys. These could be surveys of chip stockpiles at the Tamar woodchip mill, crushed metal stockpiles at the AFH quarries, coal, clay, and salt stockpiles at the APPM Burnie mill.

Again, these would be carried out using a theodolite and survey staff, with the measurements taken as stadia reading from the staff and recorded in a field book. It was usually a minimum 3-man task with Bruce on the theodolite, me on the staff and a “ring-in” doing the field book entries as Bruce called them out.

The woodchip stockpiles were an epic undertaking, sometimes more than 50,000 cubic metres in volume.

A typical survey of these would result in 200-300 individual measurements and recordings and would take all day just to do the fieldwork. Once back in the office, each measurement had to be calculated using logarithmic tables because it wasn’t until the early 80s that Bruce could purchase an HP45 electronic calculator!

The reduction of the measurements was my task; depending on the number, it could take 2-3 days to complete. Once this was done, the survey had to be plotted. Again, this was my task, and it was done on A0 sheets of paper using a protractor and scale ruler. Each point was plotted with the point number and RL (Reduced Level) written next to it. From this, we then had to divide the points into 0.25 metre contours and determine each contour’s area using a planimeter. Each contour had to be measured at least twice to ensure the margin of error with the planimeter readings was acceptable. This whole process would take close to a week to complete.

One memorable topographic survey Bruce & I undertook using this method was the survey of the Mole Creek limestone quarry and surrounding land. We were required to map the extent of the limestone deposit and provide a detailed plan to APPM. This job took two weeks in the field, and we stayed at the Mole Creek Hotel. I can still remember the sandwiches we got for lunch each day, made from the previous night’s baked meat between 15mm thick slices of freshly baked bread. We would get two of these each, along with a cake, biscuits, and fruit. Thankfully the work was very physical. Otherwise, Bruce & I would have had to expand our belts a bit!

Now in this spot, the area we had to survey was bordered by the Mersey River, so part of what we had to do was survey the river edge. This required me to swim in the river with the survey staff, get up onto the back, give Bruce a shot then swim to the next point. Thankfully we did this in the summer!

When we finished the fieldwork, there were over 100 pages of field notes totalling some 2,000 measurements, all of which had to be reduced, plotted, and measured as we did with the stockpiles. The final plan was drawn up on tracing film with ink pens, so mistakes weren’t easily removed. For those interested, I think this plan is still held somewhere in the Forico office at Ridgley.

As surveyors are associated with the land, Bruce and I were responsible for administering the AFH freehold. This included buying and selling properties as well as keeping a land register. As with the time, this was a paper document set up alphabetically by vendor with each title recorded accordingly with information on the County and Parish as well as area, in acres, roods & perches (ARP).

Now, this might seem quite an easy task, but by the mid-’80s, the AFH freehold estate was in the order of 250,000 acres or 101,000 hectares and was comprised of between 800-900 individual titles, then maintaining this register was no small task.

One job we had to do was reconcile the Local Government rates and State Government Land Tax notices. Now, these notices identified blocks of freehold that comprised several titles, so we had to develop a sub-register divided into Local Government areas and then into the relevant blocks of freehold. All this was done manually, and as properties were purchased, subdivided or sold, then everything had to be updated accordingly.

At about this time, the Lands Office started converting titles to metric hectares. So, we undertook to convert each title from ARP to hectares manually. Not a simple task as you had to convert the roods and perches to decimal portions of an acre and then convert this to hectares. I still remember 40 perches equal 1 rood, and 4 roods equal one acre, and one acre is 0.40406856ha! Thank heavens for Bruce’s HP45 calculator! I will discuss this in part two and how computers and databases made this task much easier.

These are a few examples of work in the late 70s and early 80s as a surveyor and surveyor’s assistant at AFH. Every survey had to be calculated and then plotted by hand onto paper or tracing paper. I had to learn very quickly how to print clearly and consistently in the fieldwork recording and on the plans. As a result, I adopted putting field records in capital letters, something which transferred into my everyday writing and is something I still do today.

I should mention that this role was much more than surveying.

Bruce and I had to look after the Burnie Mill Water Supply (BMWS), which involved water transfer from Surrey Hills’ west-flowing Wey River into the north-flowing Companion & Emu Rivers.

This involved managing two dams, Talbot Lagoon & Companion Dam, two weirs, one on the Wey River and another on the Companion River and approximately four kilometres of water race. There were also three flow monitoring stations located along the delivery route. They were maintained by the Rivers & Water Supply Commission (RWSC), but it was our responsibility to read, record and monitor them.

Essentially the process was to release water from Talbots into the Wey River and then, at the weir on the Wey River, divert it into the water race, where it was transported to the headwaters of the Companion River.

This water was then stored in Companion Dam and, when required, released to flow down the Companion River into the Emu River and ultimately arrive at the APPM pump station at Fern Glade in Burnie. The process took 4-5 days for the water to reach Burnie, depending on the flows in the Emu River.

Another sliding door moment was when I was at the Wey River weir, where an RWSC flow monitoring station and an RWSC representative turned up. He was Chris Thompson, who, 35 years later, was to become an integral part of my role with Tasmania Irrigation—ironically managing water supply to irrigators and operating dams!

One of the more challenging roles in managing the BMWS was the opening and closing the main outlet valve on Companion Dam. For those unfamiliar with Companion Dam, the outlet tower is some 25-30m off the upstream face of the dam wall and was only accessible by boat! Boat was a bit of a stretch. It was just a dingy, launched from the boat shed on the eastern bank, down some rails until we reached the water. If the dam was low, sometimes you had to carry, push, and drag the boat to the water. We would then row out to the tower, tie the boat to the vertical access ladder, and climb up. Invariably on the days we had to do this, there would be a strong southerly wind blowing that would put up quite a swell and waves on the surface, so rowing out and back could be a challenge, and we didn’t have life jackets either.

On one occasion, the rope came untied, and the boat was blown onto the downstream face, so one of us, me, had to swim to retrieve the boat and then row back to get Bruce. The lifting mechanism for the gate was a hydraulic ram, the same as those on dozers and excavators, with the hydraulic fluid stored in a tank out on the tower. To raise the gate, you had to connect the hydraulic hoses from the tank to the ram and then pump a lever up and down. To lower, you had to swap the hoses over. If water got into the oil, which was often the case, we would have to purge the oil from the tank and replace it with fresh oil.

Now, this new oil had to be carried out in the boat, up the ladder and then poured into the tank on top of the tower. The tower was 1.5 metres in diameter, so with all the hydraulics, the ram, and the tank, there was little room to park yourself whilst doing anything up there.

Bruce & I were also given the role of catering for visitors to Surrey Hills. There were two chalets, one at the Leven River and another at the Arthur River. Another one was built at the Companion River in the late 1990s. Catering consisted of providing a BBQ lunch of at least 300 grams of T-bone steaks, thick beef sausages, bread, soft drinks, and, if the visitor were VIPs, fruit salad and cream and alcohol finished off with tea or coffee. These were major events to organise, particularly with the timing of the cooking to coincide with the visitor’s arrival. Unfortunately, the Leven chalet was in an area where the then AFH radio system was patchy at best, so you would have to park the car where you could get radio reception up to 20-30 metres from the chalet. Needless to say, there were some anxious moments when we got a call to say that the visitors were at the top of the hill and about to descend to the chalet, meaning they were about 10 minutes away! Thankfully most people like their steaks medium rare on those days.

Another area of responsibility under the surveying portfolio was managing the AFH carpenters. When I started with Bruce, there were two carpenters, Harry Cox and Royce Reid. Lawrence (Lofty) White joined later when Harry retired. The skills of these guys were many and varied to match the jobs they had to do. From building bridges and timber warehouses maintaining company houses and buildings to cleaning out blocked drains.

I was fortunate to be able to work as an offsider to these gentlemen on many projects, perhaps the most memorable was the construction of the bridge over the Arthur River on Junction Road and the outdoor education centre at Guildford.

In the early period with Bruce, I was privileged to work with several “legends” of AFH. Thankfully, these people transferred their considerable knowledge and experience to me and other younger foresters before they left.

I still remember spending some days in Parrawe with Bill Huett, Frank Sheridan, and later Brian Roberts. They showed me why it was so important to get the location of the road and landing sites right. Then putting this into practice with the road location and what impediments to construction there might be. When you put Bill, Frank, Brian, Teena and Bruce in the bush looking at a road location, you quickly knew just to sit back and listen and learn.

Or just spending a day with Max Tippett, talking about all things AFH, surveying, roading, logging, plantation establishment, selling sawlogs, bundling pine, meeting the Prime Minister. You name it, Max was able to speak about it. He was a real raconteur about forestry and everything else, plus he had a wicked sense of humour. He was a great influencer within AFH and shaped many careers.

Then you had the Chief Forester Ted Crisp and Ross Hills, both experienced foresters. Ted always seemed to have a cigarette going, and you always knew that things were serious if he put the cigarette down or, even worse if he stubbed it out.

I can still remember Ross asking Mort Bloom, much to his consternation, to remove the stripes from his new Datsun ute when it was delivered to the AFH carpark. It proved more difficult than expected, with the car salesman saying it would require a repaint of the ute. I never found out if Mort had worded up the salesman, but the stripes stayed anyway.

While on the subject of this ute, it was undoubtedly Mort’s pride and joy, and he took every opportunity to wax lyrical about its capabilities. However, one day stands out in my memory. We had been running a road line in Junction Road, Parrawe. We had to cross the bridge over the Arthur River to get out there. This bridge was a low-level bridge, and the gravel surface was frequently washed away, leaving just the stringers and bed logs.

On the way out, Mort in his Datsun navigated safely across the bridge, but the Toyota Landcruiser I was driving slipped off one of the stringers and sat down on the front and rear diffs. Mort, always ready to help, backed up the Datsun to the edge of the bridge, and we attached a snatch strap between the Datsun and the Toyota. “You get in the Toyota, and I will pull you off the bridge,” Mort said. I quickly realised that if he did manage to do this, we would never hear the end of it, so when I got in, I put the handbrake on and kept my foot on the brake. Mort’s little Datsun spun the back and front wheels, and kangaroo hopped, burning a fair bit of rubber off all four tyres, but the Toyota wouldn’t budge! He tried for several minutes before I suggested we might have to try another option. He reluctantly accepted defeat. We did get the Toyota off, but I didn’t tell Mort what I had done until we got back to the office.

In the office, Bruce & I shared the space with Jim Barbour, the manager of maintenance and Ellis Ashton, the AFH Emu Vale Stud farm manager. Jim’s phone or radio was forever going off with all the maintenance requirements of the AFH equipment channelled through him. His ability to diagnose, find spares and fix problems all the time was something to behold. Ellis always would find the time to speak with you and make you feel part of whatever he was doing and be interested in what you were doing. His advice to me that after three days of easterly weather at Burnie, you would get rain on the fourth day was usually correct!

Then there was Snow Turner! I know Robert has written a recent piece on Snow, so I won’t elaborate much more than saying that the stories were all true!

Rounding all these characters off were the operators. I must confess a particular bias toward the road construction operators. This is because so much of my time was spent with them. They turned the flagging tape line into a logging road and watching them work still brings back feelings of awe and appreciation for their skills. When you had Merv Pyke working the D9 on a side cut or ripping material in a quarry, you could see every move as an extension of his hands. His brother Len, Mort and Lawrence Bloom, Peter Mason and Peter Burgess were people who could make a dozer do things that seemed nearly impossible. These skills meant that AFH could build forestry roads to the highest of standards but also at a low cost.

One of the other tasks everyone shared was fire management. My role was principally to man the fire tower at Nolan’s Hill, and I spent many a week or weekend sitting up in the tower, which was about two metres square in area, looking out to all points of the compass. As more plantation development occurred on Surrey Hills, the ability to view the area south of St Valentines Peak from Nolan’s Hill became problematic. Our carpenters, Royce & Lofty, relocated the tower to Companion Hill. This was no mean feat, as the site on Companion Hill could only be accessed by walking. The tower was dismantled, and the building was lifted onto a crane truck. It was reassembled on site, with the building replaced by the crane—just another example of the ingenuity and capabilities of the people at AFH.

We were fortunate that we didn’t experience too many major fires impacting AFH’s areas of responsibility in my time. However, there was one major “over achievement” out in Parrawe when a regeneration burn did expand the original area. For those who know the Parrawe area, it is not the place you want to fight fires with steep gullies and sharp ridges. This fire took over two weeks to contain and involved nearly all AFH’s equipment, people, resources, and contractors.

When I look back over these early years with Bruce and these people, I can unequivocally say that they were amongst the most formative, exciting, and happiest days of my working life. Of course, work was fun, but you knew each day you would learn something new from this band of brothers.

I would like to thanks to Bruce Hodgetts for providing photos and checking the anecdotes in this blog.

That’s a great read Mike. It was the best of times.

Tis sad to recall the demise of that great paper industry and all the organisation from forest to ship but then nobody wants to use paper anymore. All that remains is a chip mill and a few of relics in one of which I served my last working years.

Mike – a great trip down memory lane!

There is something to be said for the days prior to computers, mobile phones, text messages and demands of instantaneous responses!

I recall inter-company memos between Ridgley and Burnie or Tamar that would take several days to get a response.

A “day in the bush” was just that, “a peaceful day in the bush”!

Great read. – Bruce would remember an incident in the late 1980’s, when there was a severe drought, and we were trying to save water at the Burnie Pulp and Paper mill.

I was working on projects and was was requested to cut usage. After a week of cut backs at the mill I measured the flow height over the Fern Glade dam. I found a formula (Francis Modified Weir Formula) and calculated that approx. 2 million gallons a day was flowing out to sea.

I rang Bruce and asked him to cut the flow by 1 mgd. Bruce knew how many valve turns at Companion was required and that it would take about 3 days to get to Fern Glade.

He did it on Tuesday and on Friday there was no change so I asked him to make a bigger change.

Sunday 6am and the Shift Engineer rang. The pulp mill was shut and fish were flopping in mud at Fern Glade dam. I rang Bruce and he opened the valve quite wide and luckily by late afternoon the Fern Glade dam was filling.

Mike we did have a great team of self motivated people didn’t we. Those days will never be forgotten. It was a pleasure to have worked with all those mentioned.

Thanks for the memories.

I have just had a most enjoyable time reading Mike’s very detailed and well written blog.

I think I knew just about everyone he mentioned, so his story brought back many memories of some wonderful AFH characters, all of whom I enjoyed working with over the years.

The work Mike, Bruce and others did seems “super human” when we see the vast variety of operations they were responsible for.

Although it’s a long time ago, I won’t forget my time with AFH, they were very good years.

As usual, a very good read.

Thanks for sharing your memories Mike.

As a young surveyor, I was fortunate to spend some time working with Mike at AFH. It was a great experience working in forestry. I learned a lot about forestry and surveying. A great group of people who made working enjoyable.

An excellent read Mike. A most enjoyable account of life in the forest surveying, constructing, managing and enjoying life.

Regards, Dennis.