This is a story to illustrate an instructive lesson on active land management. It involves animals including humans, plants and forces of nature.

My story is a call to arms to highlight that our land management issues are not straightforward and the solutions require the fortitude to go against elitist and misguided orthodoxy. For too long, people parading as experts have monopolised the spotlight by offering a convenient, but flawed narrative. These “experts” are in government agencies, conservation groups, environmental consultantancies and academia. All they bring to the table is a simplistic preservation ideology that cannot address the land management problems in the tropics.

I will use Kakadu National Park (KNP) as the case study. KNP has experienced a relatively long period of preservation management; however, the park isn’t faring well. The preoccupation of the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (ANPWS) to conduct broadscale burning only in the early dry season, supposedly to mimic traditional burning, and their inability to conjure a more complex fire management program to suit the modern landscape, highlights the essence of the problem.

The setting

KNP is one of Australia’s most iconic places to visit. Situated in Australia’s tropical north, it is a must-see destination.

Aborigines held sway in the Arnhem Plateau from European dominance until after World War II. After the war until the 1970s, the southern area was managed as two immense cattle stations before it became part of KNP. The northern region was a hide processing industry hub using feral Asian water buffalos (Bubalus bubalis).

The government dedicated KNP in three stages between 1979 and 1987. Many of its outstanding natural features – a stunning sandstone sheet and associated escarpment, unrivalled wetlands covering over 67 per cent of the total park area, and over 5,000 galleries of Aboriginal rock art – were first recognised in the 1960s. However, before the government could seriously consider recommendations for a national park, geologists discovered significant uranium deposits. Consequently, they delayed any decision for more than a decade while they carried out an environmental impact study and an Inquiry to allow mining of the uranium.

The Inquiry recommended the staged declaration as a national park after considering a range of competing interests. It is now the largest national park in Australia and one of the largest in the world. Since then, the area has been managed with biodiversity conservation as a primary goal.

The new managers, ANPWS, removed cattle, and a successful eradication program was implemented to eliminate many of the feral buffalos.

The park is one of the world’s first jointly managed parks between a public institution and indigenous communities. An initial management decision of consequence was to carry out all burning in the early dry season, purportedly to follow what was believed to be traditional Aboriginal practice.

Kakadu’s prevailing tropical climatic conditions favour the rapid development of grassy fuels supported by a reliable high summer rainfall. The long dry season cures the grasses. This means that fires occur in the same area annually or biennially where around 45 per cent of KNP burns each year. Fires and savanna are co-dependent – one cannot exist without the other, creating a biome that is the most fire-prone in the world. Lightning at the end of the dry season can start large hot fires, but their impact depends on the human fires lit earlier throughout the dry season.

Older management

Fire is the critical component of the area simply because Indigenous practices shaped it for millennia. The archaeological record suggests that Aborigines have continuously occupied the Kakadu region for up to 60,000 years.

However, it is a total misnomer to suggest Aborigines only burnt in the early part of the dry season. Pre-1890, there was very little spear grass (Sorghum spp) across the Top End, outside of the woodlands, so early burning would have been difficult. Instead, they burnt mainly throughout the 91/2-month dry season using different techniques. Based on the views of older Aboriginals alive today, it is also believed that they burned all year round, even in the wet season.

Traditionally, Aborigines lit some smaller fires at the start of the dry season associated with spiritual sites, yam beds and to prepare macropod drives, usually along the margins of the floodplains. Their aim was to level any spear grass that was present. The floodplain fires were set in stages, weeks apart, and burnt from the previously burnt strips towards the wetter lower-lying areas where they fizzled out by themselves. Consequently, the central parts of a floodplain could be fired as late as mid-November, months after burning was initiated on the margins. The fire-induced production of a green pick attracted macropods well into the dry season.

During the mid-year winter season, burning was systematic and purposeful, utilising the cool south-easterly winds as the Aborigines moved around the country well away from their campsites and settled areas. The flowering of ever-present woollybutt trees (Eucalyptus miniata) signalled the beginning of these burns. Burning focused initially on cured grasses on higher ground, progressively turning to moister sites as they dried out. Fires were lit under the windiest conditions during the middle of the day to achieve a bent convection column to minimise any tree scorch, mainly to protect the flowers of fruiting trees. These broadscale fires were usually of low intensity because of the relatively low fuel build up, were patchy and led to a mosaic of burnt and unburnt country. Despite the perception of a lot of burning, estimates show about 40 per cent of the “burnt” area remained unburnt.

Towards the end of the dry season, as the relative humidity reached its lowest point, fires were more controlled and smaller, burning into previously burnt areas. However, in the woodlands the fires tended to be hotter and larger because the uniform understorey of spear grasses burnt with greater intensity. The primary purpose of these burns was to encircle kangaroos and wallabies hiding in the unburnt patches during the day. In addition, these fires helped concentrate the animals in favoured hunting areas because new herbaceous growth occurred after early wet season rains.

However, one overriding principle ensured burning could occur at any time. It was associated with the Aboriginal preoccupation of maintaining a “clean” country. Aborigines abhorred areas that were “dirty” with rank grass, thick leaf litter or a tangle of undergrowth. It signified land that was not being adequately maintained. Fires that resulted from their obsession for a clean environment, especially those torched late in the dry season, could be sizeable destructive fire events, something Aborigines were aware of when implementing corrective burning. These generally occurred in the more isolated and least-visited areas of their territories and so they were comfortable with hotter fires in those areas.

Aborigines knew the role of fire in various ecosystems over time, and their fire management system was quite complex and certainly much more than just a knowledge of tools and techniques for making fire. Because they exploited a wide range of resources, they knew the beneficial effects and counter-effects of burning intimately.

Old management

Whereas traditional Aboriginal burning practices involved the selective setting of fires at various times of the year across multiple habitats to influence the spatial distribution of a broad range of plant and animal resources, European pastoral burning practices differed entirely. The pastoralist’s burning was solely to maintain the productivity of a single species – their cattle.

Pastoralists generally started and finished their early season burning before the Aborigines, mainly because they only had one resource to cater for. The areas burnt were also much larger at this time of year, the aim being to create the maximum benefit for cattle rather than a mosaic of burnt and unburnt patches. Their burns were completed around mid-June, after which the soil moisture was insufficient for a green pick post-fire.

Large areas were also unmanaged after the decline of Aborigines in the country, which was little used by the pastoralists. Central Arnhem Land was one such area. Fires in the late dry season from lightning, in very sparsely settled areas, or in a few cases, deliberately lit, would burn unchecked over extensive areas and sometimes extend westwards into KNP.

The blame for these fires was placed solely on the pastoralists, even though the significant late-season burns were simply a symptom of a lack of burning that took hold once the influence of Aborigines on the land declined. They were accused of deliberately lighting their green pick fires at this time, even though a fire at that time provided no benefit to them apart from providing assistance with access when herding cattle. This narrative took hold when the academics, bureaucrats and environmental consultants from the cities descended on KNP after its dedication as a preservation reserve.

These large uncontained fires prompted the establishment of the West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement project (WALFA) on the rugged lands to the east of KNP, which began in 2005. The project is a contractual arrangement between ConocoPhillips and the Northern Territory government to generate a greenhouse gas abatement credit of 100,000 tonnes per annum by controlling and timing fires over a 28,000 square kilometre area that was largely previously unmanaged for many years. The money comes from the generous tax payer funded $2.5 billion Emissions Reduction Fund. The revenue generated from emission offsets helps fund fire management over the West Arnhem country, which went from zero dollars to over $1 million overnight.

This project quickly turned the onus of responsible fire management back onto the managers of KNP. They no longer had to deal with unwanted fires from West Arnhem. Instead, they now had an obligation to ensure fires they lit on KNP did not enter the WALFA region from the adjoining rugged Stone Country.

Colonising and thundering across the plains

Meanwhile, an interesting wild ruminant came between the older and old management regimes. Indonesians introduced buffalo to northern Australia in the 1820s. They were first recorded at Kakadu in 1845 by explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. Stumbling across buffalo dung towards the end of his arduous expedition ended his fear of starvation. His men shot a young bull, and Leichhardt shared the meat with local Aborigines who knew this animal well.

In 1826, English settlers introduced about 80 buffalo to Fort Dundas on Melville Island and some were transferred to the Coburg Peninsula in 1828 to supply meat in the remote northern settlements. More buffalo were imported to the Victoria settlement on the Coburg Peninsula in 1838. They successfully domesticated the buffalo, keeping herds at low densities until around 1849, when the settlements were abandoned.

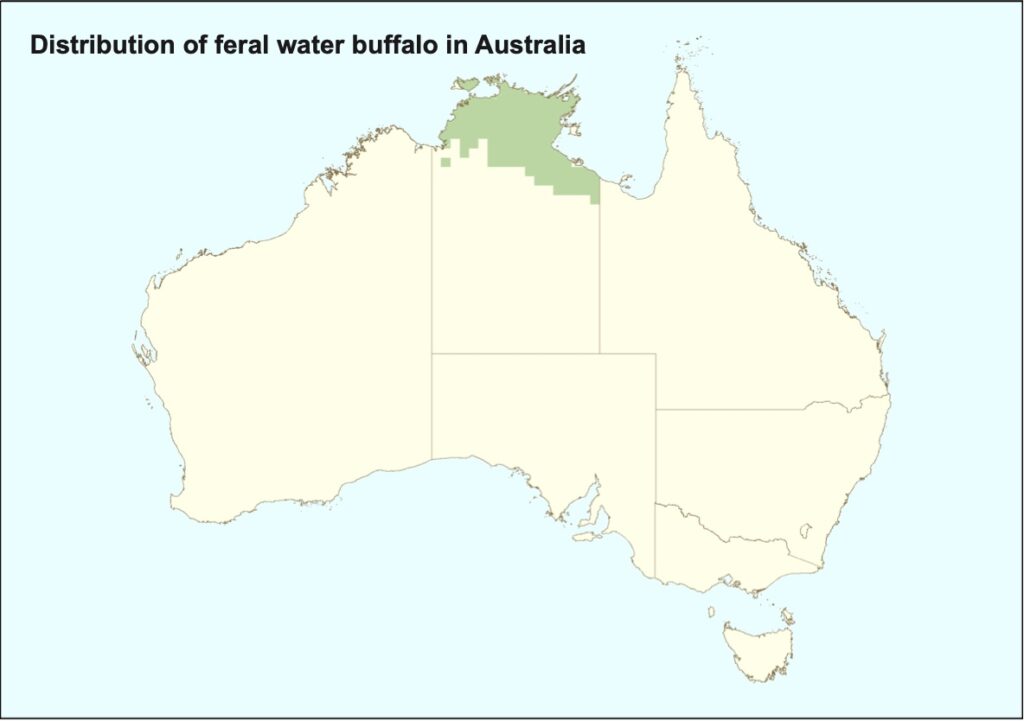

Buffalo were left behind, and they were either released or escaped. Their descendants expanded across the peninsula into permanent and semi-permanent coastal swamps, plains and freshwater springs of the Top End of the Northern Territory. Numbers swelled to over 350,000 a hundred years later, more than half the world’s wild population, occupying the 20,000 square kilometres between the Adelaide and East Alligator Rivers.

The expanding feral buffalo population provided an economic resource through their hides, meat and live export. Hide hunting began in the 1880s but did not gain momentum until the turn of the century when overseas demand increased. Introducing a more efficient means of horseback shooting helped meet the demand. Over nine decades, some 700,000 buffalos were harvested.

In 1900, 1,645 hides were exported from the Northern Territory, and exports climbed rapidly after that and remained above 5,000 per annum for over half a century. So important were buffalo to the Northern Territory economy that in 1920, the acting administrator recommended protecting buffalo on the offshore islands as they were “fast becoming extinct on the mainland”.

However, the hide industry collapsed in 1956 after synthetic materials replaced buffalo leather for industrial belting. In a year, hide exports in the Northern Territory dropped from 5,663 to 100 hides. After a brief hiatus, live exports increased, and harvests in the 1960s and 1970s exceeded those of the hide era. This was due to local demand for buffalo meat and pet food and an initiative of the Northern Territory Agricultural and Animal Industry Branch to redevelop buffalo as a viable economic resource for the Top End.

The number of buffalo grew alarmingly to the carrying capacity from 1960 to 1980, altering the character of the northern floodplains. Buffalo removed native grasses by selectively grazing. This benefitted spear grass which became unpalatable as it matured. Authorities knew that feral buffalo also carried several cattle diseases, most notably tuberculosis and brucellosis. The former, in particular, was found to pass from bovines, like cattle and buffalos, onto humans.

A Board of Inquiry was established in 1970 and it determined that feral animals, particularly buffalo, were a major source of concern for the cross-infection of domestic bovine herds. As a result, the government decided to cull the buffalo to minimise the risk to any surrounding cattle or humans of contracting tuberculosis. A buffalo eradication program could also enable the certification of Top End beef for export by controlling tuberculosis and brucellosis infection rates among domestic cattle.

The Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign (BTEC) was introduced in 1979 by mustering live animals and then ground shooting the densest feral buffalo herds on the northernmost floodplains. Expert shooters in helicopters were later introduced to remove buffalos in other areas. As a result, buffalos in KNP were virtually eliminated as numbers fell to around 250 in 1996. However, the last remaining populations were in isolated rainforest pockets and ravines of the rugged Arnhem Land plateau, which meant complete eradication was impossible.

Nonetheless, BTEC was a remarkable success in eradicating feral buffalo from KNP and the Top End. However, it remains highly controversial to this day, particularly among tour operators and Aboriginal communities who believed the campaign was a threat to their livelihoods. While the BTEC only covered Arnhem Land on a very small scale because densities of buffalo at the time were very low and risk of disease spread was seen as minimal. That has changed over the years and buffalo numbers have become a problem again, despite the Kuninjku people in the Maningrida region of West Arnhem Land being reliant on buffalo meat as an important source of protein and a staple food.

Tour operators argued the buffalos became a treasured symbol of the Top End. In 1992, biologist Bill Freeland wrote in the Australian Natural History magazine:

“It was and is part of things Territorian, and its apparent demise something many regret. While noting that, yes, it had a negative impact on the environment, there is something sad about the current status of the buffalo population. The Top End’s water buffalo, in a sense, provided a substitute for our lost marsupial megafauna. Nowhere else in Australia could you see vast herds of large herbivorous mammals (large horns and all) thundering across the plains – an unusual sight for Australia. Unfortunately, however, something went wrong and, as well as a megafaunal replacement, we ended up with a major environmental problem”.

As a kid I recall the reference to Vietnam veterans used in the buffalo culling. Anthropologist Basil Sansom wrote about the “Holocaust of the buffalo” referring to the aerial militarised massacre of buffalo from “helicopter gunships” using Vietnam veterans as professional platform shooters.

Current management

Unfortunately, the unintended ecological consequences of removing buffalo were not at the forefront of the BTEC program. The same can be said of the removal of cattle in KNP. Rapidly removing a significant grazer from the floodplains and billabongs resulted in large-scale ecological change. Both native and alien plant species spread to cover the areas formerly laid bare by the buffalo in the floodplains. Spear grass exploded across the landscape, covering about 60 per cent of the lowland savannas. The spread was accentuated by the decision to burn early in the season.

Until the eradication program began, thousands of buffalo ate an estimated 40 kilograms of grass daily. Once the buffalos were removed, biomass returned vigorously to the damaged wetlands, including weeds such as para grass (Brachiaria mutica), and the intensity of the dry burns increased.

Pre-1890, there was very little spear grass across the Top End, so early burning would have been difficult. As a result, most of their burning was in the mid or late dry season. Fire scar mapping in 1996 supports this. Much of the Aboriginal-managed Arnhem Land was burned in the middle to the late dry season, while the remainder of the Top End, managed by Europeans, was burnt early in the season.

The ecological consequences, firstly of an expansion of buffalo numbers and secondly their sudden removal, created two ecological cascades by altering ground cover abundance and composition, which in turn affected competitive regimes and fuel loads with possible long-term effects due to changes in fire regimes. Through selective grazing, buffalo removed perennial native grasses to favour sorghum and spear grass which became unpalatable when it matured. However, they heavily grazed the floodplains, which created an artificial firebreak that, surprisingly and never acknowledged, allowed wildlife to boom in the wetlands.

While Kakadu is Australia’s largest national park with plenty of funds to aid in management, the focus has been on fire management to deal with an increase in fuel loads which led to the development of a sustained large-scale fire management program in the park.

The intent was to follow traditional Aboriginal practices “as closely as possible”, but that ideal has been difficult to achieve. Initially, the annual burning-off program relied on resident groups of traditional owners burning off and rangers lighting from roadsides. However, with few traditional owners left in KNP, those there walked less and didn’t live in or near the open forest or woodlands. Therefore, in the early 1980s, too little burning was carried out before the weather became too hot and dry. Additionally, the ideal time set for rangers to burn was short and coincided with other peak demands and priorities for visitor management.

This led to catastrophic late dry-season fires, put ANPWS at risk of damage claims outside the park from neighbours to the west, and caused damage to the park’s biological and cultural assets.

In 1985, ANPWS found that the most efficient way to achieve its aims was to introduce aerial burning. They now burn as much as possible before the end of July and ensure firebreaks are in place and maintained.

In many ways, the new fire management regime is less about mimicking traditional management and more about ensuring enough broadscale hazard reduction burning is carried out annually, even though they fail to acknowledge this. Their method of firing the country wasn’t new as foresters developed a similar and very sophisticated fire management system in Queensland, south-eastern Australia and south-western Western Australia to manage fuel levels in the forests. The main difference was that ANPWS’ program has to be implemented annually or biennially in tropical areas to deal with the annual grass fuel build up.

The problem

While ANPWS claim to manage KNP jointly with the traditional owners for fire management, the reality is that Aborigines have felt disempowered and marginalised when it comes to fire management. They believe they have few opportunities to participate in decision making as they witness a form of fire management alien to their traditional practices.

Since its inception, the ANPWS fire management program has successfully met its aims. Shifting the seasonal timing of fire on a large scale towards fire much earlier in the dry season protected the park against hotter and more widespread late dry-season fires. However, a change such as this on a big scale, and so quickly, was bound to have ramifications.

The intrusion of western science to replicate Aboriginal traditional burning practices has failed to incorporate the nuances of the older management. Aborigines developed an innate ability to respond to their ever-changing environment during the year and applied a truly adaptive approach. They were on the ground and didn’t have to drop other things to muster resources to do the job. They just did it when required. Unfortunately, the managers, consultants and academics who control fire management at KNP have long held a deep-seated belief that they had the right ideas for fire. Several workshops held in the 1990s reinforced that confidence.

Too much self-belief without critical self-examination, prevalent within the Australian public sector, generally promotes congratulatory gestures among themselves under flawed key performance indicators. But it has no relevance to the landscape they manage. ANPWS have continually failed to adopt an adaptive management approach to suit the post-buffalo environment. This is because failures are never acknowledged, and improvements are never sought.

Put simply, there is too much carelessly applied fire in the wrong part of the season.

Burning mainly in the early dry season, has reduced plant flowering and fruiting success and the growth of dominant savanna eucalypts. It has also reduced the availability of grass seeds for ground birds such as finches and partridge pigeons. A single cathedral mound full of termites eats the same amount of grass yearly as an elephant. Early burning has reduced the availability of their food, thus affecting their numbers. A reduction in flying termite breeders also affects the food source of many other species dependent upon them.

Consequently, since 1996 there has been an alarming reduction in native mammal species such as the northern quoll, fawn antechinus, northern brown bandicoots, pale field rats, and possums. A study in 2009 highlighted this decline.

John Woinarski opined that part of the reason for the losses was that “the experts are not to be believed”. He argued that species were more vulnerable to chronic, pervasive, insidious and cumulative threats, and these factors drive Australian species to extinction. However, the problem is these “experts” fail to offer practical and pragmatic solutions other than arguing that Australia’s central conservation policy and legislation should be changed, or more areas should be preserved.

I think there needs to be a more pragmatic and realistic appraisal of the situation. Neither ANPWS nor academics recognise the buffalo conundrum that led to a completely different landscape. Before European settlement, the floodplains were a rich resource for Aboriginal people who burnt the floodplains extensively. The arrival of buffalo in the region coincided with European settlement and Aboriginal depopulation, hence a decrease in both human sources of ignition and fuel loads. During the peak buffalo period, burning in many floodplain situations was no longer practicable or feasible. However, once buffalo were removed, traditional fire regimes were not resumed on the depopulated floodplains as fire is seen as bad for these areas. Nor was it ever practicable because of the spear grass invasion.

Although fire use by Aborigines declined at Kakadu after European settlement, pastoralists and buffalo-hide shooters continued sporadic burning to promote green pick early in the dry season and, during mustering, dispersed herds late in the dry season. Reducing fuel loads made it easier to ride and drive over the country. Pastoralists also liked to use fire to entice animals to areas for muster.

Unfortunately, several influential papers on traditional fire management in the Top End reported traditional Aboriginals burning was only carried out early in the dry season and that Aborigines avoided late-season fires because they were dangerous and destructive. This false narrative took hold, despite historical evidence that showed fires were used throughout the dry season and were not necessarily focused on the early season. It is generally known within the Aboriginal community that burning commenced in the upland Stone Country after the cessation of rains and gradually moved towards the lowlands as grasses cured.

Are there any solutions?

ANPWS must look closely at reversing the grass-fire cycle they find themselves in at KNP. For example, they can use fire to reduce the competitive ability of spear grass by carrying more wet season burning in areas supporting old spear grass. This could remove the grass for up to five years, allowing native perennial grasses to return and achieve a greater diversity in annual grasses. Alternatively, they look to introduce exotic herbivores such as cattle or even reintroduce buffalo in low numbers to keep the spear grass in check. It is not widely known that just prior to the successful BTEC program, there were some encouraging attempts made to domesticate small herds of buffaloes rather than cattle.

I believe it is too romantic a notion to obsess over adopting traditional burning practices. Because of changes wrought by European settlement, the landscape has changed due mainly to buffalo, pastoral activities, and a lack of continuous traditional burning for over a century. The reality is Kakadu is less an Aboriginal environment and more a European one. Secondly, the managers need to be more responsive to their problems and be prepared to unshackle themselves from the constraints of a preservation dogma that limits the options they could use to improve the management of KNP and save the disappearing mammals.

Final word

In the aftermath of the 2019-20 Black Summer, where eight million hectares were burnt, the elitist chattering class pushed for more traditional or cultural burning to be reintroduced into the landscape as part of the solution to the increasing wildfire problem. It was as if low-intensity burning was a new concept since European settlement.

It didn’t matter to them that foresters had already introduced a sophisticated prescribed burning program across the new modern European landscape to successfully reduce fuel loads in the forests of eastern Australia and in the south-west portion of Western Australia. While the intensity of the burning matched the cool fires set by Aborigines, it was designed to meet the constraints of a modern advanced country, now supporting 24 million people, and could be adopted in the post-Aboriginal landscape.

The problems at KNP highlight the near-impossible task of maintaining cultural burning in a much-changed landscape, even though it involves Aborigines who maintained some form of traditional land management as late as WWII.

The reality is ANPWS must deal with a massive annual fuel build-up problem. They have tried to deal with this problem by implementing a modern prescribed burning program using current technology, including helicopters, incendiary devices, GPS, bitumen roads, four-wheel-drives with water tanks, and bulldozed firebreaks. There is nothing wrong with that, except that just because an Aborigine lights the fire does not mean it is traditional burning. Their preoccupation with limiting burning to a set part of the season has only compounded their environmental woes.

ANPWS can improve their land management if they are prepared to over ride the green ideological obstructions that preclude introducing various practical options. One of those would be the reintroduction of cattle or domesticated buffalo to help manage the alarming spear grass issue. While green activists and academics think that option would be totally deleterious to the environment, one only has to point out the long term study carried out by the CSIRO’s Division of Wildlife and Ecology at their Kapalga Research Station in KNP. They erected a buffalo fence across the station in 1981 to compare grazing by buffalo to areas excluded. The study offered the only experimental evidence of the effects of buffalo on the Top End’s ecosystems and it only ended with the introduction of the BTEC program. Their work showed that although the buffalo had a detrimental effect on wetland habitats, there was no loss of species and the ecosystem recovered quickly after buffalo were removed.

The other option would be to stop the preoccupation with trying to mimic traditional older practices and focus instead on utilising a fire management program to suit the environment they have to manage today.

Interesting commentary, and largely consistent with the message of this new article in The Conversation re the role of large feral herbivores: https://theconversation.com/horses-camels-and-deer-get-a-bad-rap-for-razing-plants-but-our-new-research-shows-theyre-no-worse-than-native-animals-221873?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20February%202%202024%20-%202866729082&utm_content=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20February%202%202024%20-%202866729082+CID_bf1de905fb86ce2b3d0785c6b8f7f9e1&utm_source=campaign_monitor&utm_term=Horses%20camels%20and%20deer%20get%20a%20bad%20rap%20for%20razing%20plants%20%20but%20our%20new%20research%20shows%20theyre%20no%20worse%20than%20native%20animals

“Because failures are never acknowledged “. Nor I add, unbiased evaluation of outcomes.

Excellent article Robert. How to change bureaucratic culture to be responsive to outcomes and not political and monetary outcomes?

This article touches on issues that Australia has many different ecosystems, set in different climates. Then broken down to micro ecosystems, in micro climates. Add to this the modern human population levels, demands and the changes this makes. The business of environmentalism that one generation of school room academics, train the next generation of environmental career academics.

The link to better understanding these infinite different ecosystems would be the local community. Yet I would suggest that the business of environmentalism has been so successful in removing rural stewardship, from any form of environmental management input, that the use of this knowledge and a free resource of intimate value, is frowned on.

Grazing animals and an ecologically sustainable modern environment is not just confined to the NT.

The Yarra Valley, my home, has the crazy history of the business of environmentalism that removes all rural stewardship from river reserves. It is replaced with a conservation system totally developed and reliant on the use of chemicals on the banks of rivers that form part of Melbourne’s water supply.

The other reliance is on taxpayers dollars of course once rural Australians are ostracised from any management strategy input. To be clear, they offer partnerships that must meet the constraints of their business and ideological agenda. No true rural stewardship input is required.

This gives detail to my opening question.

Grader grass (Themeda quadrivalvis) – Council of Australasian Weed Societies

“Grader grass germinated faster than 18 other species in the rangelands of North Queensland”.

Grader Grass is one of the worst examples of environmental disasters which could have been prevented south of the tropics.

This rapid mass germination and rapid growth shades out the smaller native grasses, and constant hot burning is wiping out the former forest species of grasses, shrubs and tree seedlings.

This grass began to appear along the Bruce Highway between Gin Gin and Gladstone in the 1980`s. When first noticed, I contacted the Qld Environment Minister Pat Comben and pointed out that it was only in small patches along the roadside where it could easily be eradicated with glyphosate herbicide. This advice to the minister was not acknowledged and nothing was done.

Because it was in the stock routes which are mostly ungrazed, within 10 years, it became a solid wall towering over the bitumen, and now requires constant slashing and burning. Because it grows so thick and tall it is changing the ecology of the stock routes which were a living example of what pre-settlement native forests once looked like.

Thanks Robert for this interesting insight into the management or attempted management of this area now under control of the National Parks.

I can fully understand why the local indigenous population feel like they have become somewhat redundant in regards to looking after the land they have inhabited for 60,000 years.

Look forward to hearing and seeing any thoughtful progress in this situation.