“I’ll put a girdle ‘round the earth in forty minutes”

William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

While travelling around the country, I came across yet another little-known wartime story which again highlights the heroics of Australians. This time it involves midget submarines and divers cutting underwater telegraph cables to thwart the Japanese communication efforts towards the end of World War II. The success of their daring and brave operation helped end the war with the Japanese.

The tiny submarines were relatively untested craft rejected by the US Navy as unreliable and unsafe. Undeterred, the Royal Australian Navy was convinced they were the only vessel capable of performing the mission of cutting undersea telephone cables that connected Tokyo with Hong Kong, Saigon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City) and Singapore. During the dangerous operations, five crew were confined to the tiny vessel 15 metres in length for over 30 hours.

The two related missions were as daring and risky as any the Japanese tried with their midget submarines during the war. The idea of sneaking a midget submarine behind enemy lines to disable Japanese communications was something you would expect to read in a war novel and not in real life. So it is remarkable that a pivotal diving mission was successfully carried out and helped end the Pacific War and, thus, World War II. Two Australians were involved and received war medals for their contribution.

History of cable cutting

The British pioneered submarine telegraphs by crossing the River Thames in London around 1840. They were the first to wire two continents together by laying undersea communication cables in 1851 across the English Channel. They laid other cables in 1852 to connect England, Holland, Germany, Denmark and Sweden and another connecting Italy with Corsica and Sardinia. By the time of the Crimean War, a 300-mile cable was laid across the Black Sea, allowing England and France to connect with their armies instantly.

Meanwhile, in Canada, there was a boom in telegraph connectivity out to Maritime provinces and several border crossings into the USA. The media drove the expansion of telegraph connectivity in their quest to dispatch news quickly overland after packet ships arrived.

As telegraph connectivity extended northward up the Atlantic coast, the press followed. In 1858, a cable was finally laid between Great Britain and North America after many attempts that decade.

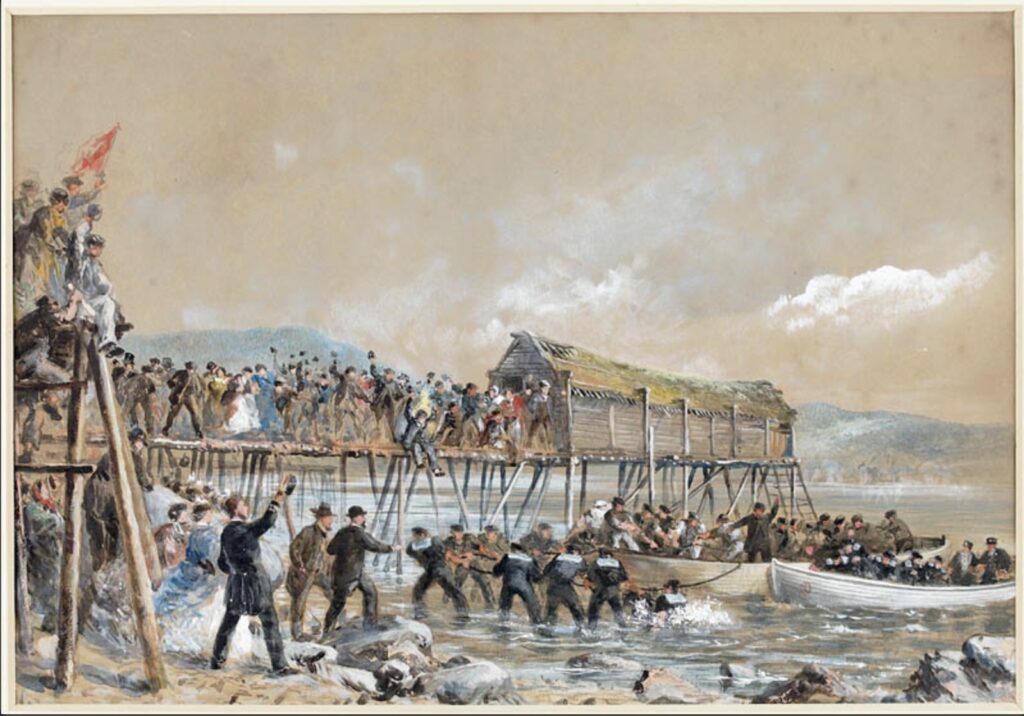

Landing of the third Transatlantic telegraph cable at Newfoundland, 1866. Painting by Robert Charles Dudley.

Telegraph communications were remarkable technology in those times as they allowed the transmission of messages instantly. Until 1911, the British submarine cable system dominated the important North Atlantic Ocean market. However, damage or cutting of cables has been a constant hazard. Fishing trawlers and anchors cut cables and natural events such as earthquakes, whales and sharks also caused damage. Consequently, several ports near important cable routes became the focus of specialised cable repair businesses.

However, it was during wartime that the enemy deliberately targeted undersea cables. It started in 1898 during the Spanish-American War when US naval ships cut telegraph lines in the Spanish possessions of the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba, isolating them without communication with the high command in Spain.

The British General Post Office Cable Ship, CS Alert, was used to locate and cut five German cables linking it with the rest of Europe in the Atlantic Ocean during World War I. The British also operated similarly on German cables connecting the German coast to Britain. Missions by other ships later in the war eliminated the remainder of Germany’s cable network. After that, Germany had to communicate by wireless transmission, which meant the British could intercept, decrypt and decode their communications. In some cases, the damaged cable was recovered by a grapnel or grappling hook and relaid at British and French ports for use by the Allies.

Submarines were also active in cable cutting. For example, in 1918, the German large, long-range U-boat submarine, U-151, cut the undersea cables between New York and Nova Scotia and between New York and Colon in Panama.

At the start of World War II, Atlantic Ocean cables were also cut by surface ships. But some of the most daring cable-cutting operations occurred behind enemy lines late in the war using XE Class mini submarines.

The X-class submarine

The use of mini submarines in warfare was not a new concept. A British submarine Commander from World War I conceived the idea of midget subs. He designed a tiny one-man craft that capital ships could release before a battle. The operator could drive his armed craft into an enemy ship and sacrifice himself for the greater good. This concept, not surprisingly, didn’t resonate with the Royal Navy but struck a chord with the Japanese. They developed the “Kaiten” midget submarines and manned torpedoes as “kamikaze” craft.

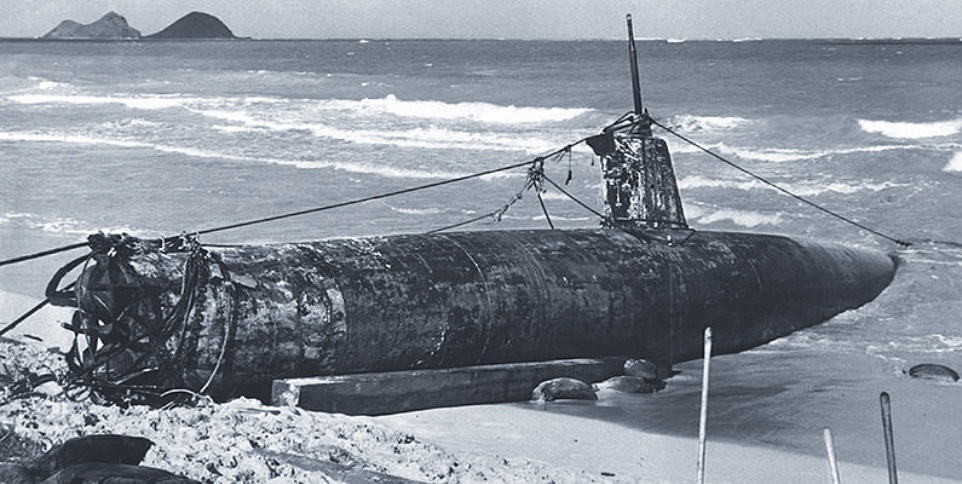

The Japanese HA-19 mini submarine washed ashore at Bellows Beach, Oahu after attack at Pearl Harbour.

The Japanese had their two-man midget submarines with some successes and failures. They were partly successful in Pearl Harbour in December 1941, where one of five midget submarines to enter the harbour fired a torpedo into USS West Virginia, sinking her in shallow water, although she was later successfully refloated and played a significant role in the Philippines Campaign in 1944.

During the 1942 Allied attack on Diego Suarez Harbour, Madagascar, a Japanese midget submarine torpedoed and seriously damaged the UK battleship HMS Ramillies and sunk the oil tanker British Loyalty.

In May 1942, five large Japanese I Class submarines rendezvoused about 35 nautical miles northeast of Sydney Harbour. A float plane launched from one of the submarines carried out a reconnaissance flight over the harbour as a prelude to releasing three two-man midget submarines to target the cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra anchored peacefully in the harbour. They failed but did manage to raise alarms and fire torpedoes. In each case, the Japanese crew were found dead with their “suicide submarines”.

The British developed several different submersible craft for the express purpose of conducting surprise attacks against enemy shipping in harbours, landing raiders, agents and saboteurs on hostile coastlines and performing surveillance operations of existing enemy capabilities and potential invasion landing sites. A midget submarine was under 150 tons, operated by a crew of up to nine with little or no onboard living accommodation. They usually worked with a mother ship, although the Japanese were different.

It was in July 1940 when the British Army and the Royal Navy met to design a small submersible craft called the X-craft, and they manufactured the first one in 1942. However, there were many deficiencies, mainly its limited submerged range and endurance, the side cargoes that carried the armaments were susceptible to leaking at depths below 200 feet, and a few electrical faults. As a result, they had high losses but did have some success with the 30-ton X Class minisubs against the battleship Tirpitz in 1943.

The sinking of the battleship Tirpitz.

The Royal Navy produced a variation called the XT Class to train ships in anti-submarine warfare. While successful, they made way for the final wartime design, the XE Class, constructed for service in the Pacific War. It had a greater displacement by about three tons and numerous design improvements.

Eighteen XE craft were ordered in early 1944, with the first six delivered by the end of that year. They had far more success during the Pacific war against the Japanese. They had a crew of four men, typically a lieutenant in command with a sub-lieutenant, an engine room mechanic and a seaman.

The men aboard the craft were crammed in a confined space for more than 30 hours, and the divers used equipment that was not very advanced. For example, they didn’t have scuba equipment and breathed pure oxygen through a hose.

In February 1945, the depot ship HMS Bonaventure, the English S Class attack submarines and the new XE Class craft formed the 14th Submarine Flotilla sent to the Pacific War. However, precisely what their mission would be once they got there was not yet clear. They stopped in Hawaii and received a frosty reception from the Americans. This was mainly because the Americans saw the Pacific War as theirs and believed there was no advantage in using mini submarines, particularly as they were winning the war with conventional submarines. They simply couldn’t see an XE Class “suicide craft” sinking anything they couldn’t via a submarine, a carrier or land-based aircraft.

The Commander of HMS Bonaventure, Captain William “Tiny” Fell, thought otherwise and travelled to Sydney to appeal to the Admiral of the British Pacific fleet, who permitted him to travel to the Philippines. However, on arrival, while he got a sympathetic ear from the Commander of the US Submarines, he was sent packing back to Sydney. The Americans simply didn’t appreciate what the midget submarines could do exactly.

Next, the Navy asked Fell if his XE craft could cut the undersea telegraphic cables from Saigon and Hong Kong, used by the Japanese to send their radio traffic by cable, which the Allies could not detect. At this stage of the war, the Japanese radio codes were already compromised, so if they could cut the cables, they would force the Japanese to revert to radio traffic where the Allies could decipher their communications. The Americans were advanced in their plans to drop atomic bombs on Japan and were in the process of delivering a final ultimatum to the Japanese. They needed to know their intentions to ensure maximum impact on the aggressors.

His missions were to be conducted under Operations Foil and Sabre and were designed to sever undersea telephone cables that connected Tokyo with Hong Kong, Saigon and Singapore. In addition, the Allies wanted the Japanese to use radio communications which the codebreakers could more easily intercept.

Training for a new job

HMS Bonaventure and the six secret XE-craft sailed to Hervey Bay, a location chosen to avoid being spotted by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft and an area deemed suitable for submarines.

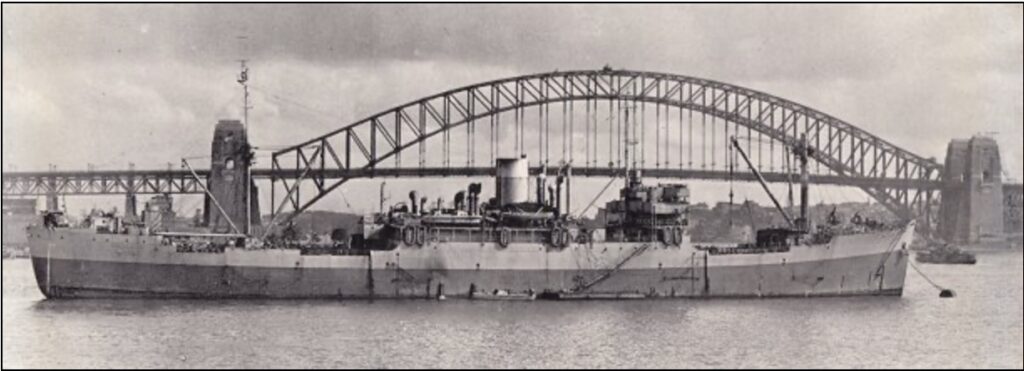

HMS Bonaventure at Sydney Harbour.

One of the tasks to be simulated was to cut underwater cables. A disused underwater telegraph cable ran between Mon Repos, just north of Hervey Bay and New Caledonia that was laid in 1893 but abandoned a few years later. The 14th Flotilla commenced trials to determine if the XE Class submarines could carry out the task of finding and cutting underwater telegraphic cables. They found a way to locate and cut the line using special grapnels.

Here, they carried out extensive experimental work to design a grapnel that could snag the cables buried in mud and silt on the ocean floor and develop the appropriate operational considerations.

Unfortunately, two crew divers were killed in June 1945 during this work. At the cable-cutting training, Commander of XE-3 Lieutenant Ian “Tich” Fraser decided to test the free diving equipment. Usually, the oxygen divers – those that dived every day and were match fit and better suited for that type of work – would do the exercise. However, Leading Seaman Mick Magennis was not available that day, and the spare diver reported a defect with his diving equipment. So instead, crew diver Lieutenant David Carey agreed to do the exercise.

The crew of XE-3 training at Hervey Bay. L-R Leading Seaman Magennis, Lt. Ian E. Fraser,

Lt. David Carey and Engine Room Officer Maughan

Carey worked with the grapnel and the hydraulic cable cutter returning to the craft a few times and signalling everything was alright. Then, as they surfaced, Fraser saw Carey jump over the side and disappear. It was the last time they saw the 22-year-old. They never recovered his body.

When Fraser returned to HMS Bonaventure, he felt he was responsible for the death of his best friend. Nevertheless, Captain Fell ordered the exercise to be repeated with a different diver. The next day, Lieutenant Herbert Westmacott Commanded the XE-2 for the training exercise, and the diver was Lieutenant Bruce Enzer. The submarine descended, and Enzer left the craft and activated the grapnel. He went through the cable-cutting exercise, but when he was in the wet-and-dry compartment afterwards, Westmacott realised something was wrong and immediately surfaced. An accompanying motorboat pulled up alongside the submarine and asked Enzer if he was alright. Enzer punched the boat driver, jumped overboard, disappeared, and was never found.

The cause of their tragic deaths was attributed to oxygen poisoning due to heavy exertion underwater in warm tropical waters, at depths exceeding the limit of their oxygen re-breathers. Carey’s case was accentuated after he had dived to a depth of 47 feet and had to work hard against the tide.

The free diving apparatus was a closed-circuit system to avoid air bubbles coming to the surface during dangerous missions in enemy-held areas. The carbon monoxide the divers breathed out was absorbed after passing through an alkaline chemical known as Protosorb and regenerated into pure oxygen. However, upon investigation, the divers had gone too deep and suffered from oxygen poisoning, which affected their minds believing they were not in danger and could cope with anything.

Two brave Australians

After these deaths, the Royal Australian Navy adopted a policy of adding a second diver to each XE craft to avoid a diver spending more than 20 metres in depths over 10 metres and no more than 10 minutes over 12 metres.

Lieutenant Maxwell Shean was born in Perth in July 1918. While studying for an Engineering Degree at the University of Western Australia, he joined the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve as a probationary Sub Lieutenant in October 1940. He received officer training on HMAS Cerberus and attended anti-submarine warfare school at HMAS Rushcutter in Sydney. His first appointment, in July 1941, was to HMS Bluebell, a Flower-class corvette which saw action in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Shean was sent to HMS Dolphin in August 1942 for submarine training and then was appointed to HMS Varbel for X-craft training. It was here he was promoted to Lieutenant on 28 April 1943.

His first X-craft mission was a diver on X-9 as part of a six-craft attack on the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway. However, the towing rope parted during the tow into the release point, and X-9 and the Passage Crew were lost. Fortunately, the crew managed to return to Scotland in HMS Syrtis.

In April 1944, Shean commanded X-24 for a solo attack on the Laksevaag floating dock in Bergen Harbour. He managed to place charges under a large coal-carrying merchant ship which was sunk, but the dry dock survived the explosion. As a result, Shean managed to escape the harbour undetected. It was the first time an X-craft returned home after a mission.

He was sent to HMS Bonaventure in December 1944. When the operation to sever telegraphic cables between Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong and Japan was determined, he was in command of the new, improved model XE-4. He was also part of the training in Hervey Bay.

Born in Glen Innes in 1923, Sub Lieutenant Ken Briggs joined the Royal Australian Navy as an Ordinary Seaman on 24 May 1941 at HMAS Rushcutter in Sydney. After training on HMAS Penguin, he saw service in Coastal Forces in the UK and took part in the invasion of North Africa under Operation Torch. In 1944, he undertook submarine training and was posted to HMS Varbel for X-craft training. He was appointed to HMS Bonaventure in December 1944 as part of the 14th Flotilla and went to Hervey Bay for further training.

Operations Sabre and Foil

With all preparations in place, HMS Bonaventure initially led the 14th Submarine Flotilla to Subic Bay and then onto Labuan Island off the west coast of Borneo. Shean was now in command of the new, improved model XE-4. On 31 July 1945, HMS Spearhead towed the XE-4 midget submarine within 40 miles of the Mekong Delta off Cap St Jacques Lighthouse to find the cable. On the way, Shean was almost lost when a wave swept him over the side during a surface passage, but he quickly grabbed a handhold and pulled himself back onto the main casing.

The XE class carried limpet mines, but they received messages that there was nothing in the harbour they could attack.

(Left) Commanding officers of the XE-Class submarines. L- R XE.1 Lt. J. Smart of XE-1, Lt. Ian E. Fraser of XE-3, Lt. H.P. Westmacott of XE-2, Lt. Max Shean of XE-4.

Using dead reckoning, Shean took the XE-4 into the mouth of the Mekong River. He had a relatively accurate layout of where the cables were. The submarine scoured the ocean floor with a towed grapnel for the two telephone cables. The grapnel caught several obstructions, which were not a cable, and Shean could back away without sending the divers out.

After several hours of dragging and a slight shift in the search area, they eventually snagged the Singapore to Saigon cable on the third attempt. The submarine lifted the cable about 10 feet off the ocean floor, where the first diver, Australian Sub Lieutenant Kevin Briggs, had just ten minutes to use a cable cutter to sever it. He returned to XE-4 with a 12-inch length as proof of the cut.

They found the second cable nearly two hours later. It was the Saigon to Hong Kong cable, and the second diver, Sub-Lieutenant Adam Bergius, couldn’t cut it with his cable cutter. He returned to XE-4 and exchanged cutters, and after a brief rest, he re-exited and finished the job. XE-4 withdrew from the area, made her rendezvous with HMS Spearhead, and returned to Labaun on 3 August 1945.

Operation Foil targeted the cables connecting Hong Kong to Singapore at the Hong Kong end. The XE-5 submarine was towed close inshore near Lamma Island by HMS Selene. However, the tow broke, and it took a day for Selene to find her and re-establish the tow. Once in place, XE-5 began lurking on the ocean floor close inshore to Lamma Island on 1 August 1945.

The working conditions were deplorable and hazardous. Due to a steeply shelving sea floor, there was only about 100 yards wide where the submarine could operate. Any closer to shore and XE-5 could be spotted, and the diver could succumb to oxygen poisoning any further out. In addition, the seabed in this confined area was covered in a thick layer of soft mud. When XE-5 bottomed, the mud came up four feet up the sides of the craft. After many repeated attempts, the divers weren’t exactly sure if they had severed the cable. It was not until after the Japanese surrendered that the British confirmed that XE-5 succeeded.

The first diver, Sub-Lieutenant Bruce Clarke, almost severed his thumb after being caught in the hydraulic grapnel in the mud, cutting it deeply and fracturing the bone. As he entered the wet and dry compartment of the submarine, he was severely stung by a Portuguese man-o-war jellyfish as he was only wearing swimming trunks in the hot tropical waters. He was in a bad way and was taken to the Selene for treatment.

On the XE-5’s return, the second diver, Sub-Lieutenant Dennis Jarvis, took over the sea floor work. Unfortunately, obstructions were repeatedly snagged using the grapnel, and Jarvis had to continually go out to check if they had found the cable. Finally, after three days of dragging and 17 passes, XE-5 withdrew with its crew under extreme fatigue.

While the operation was initially considered a failure, it was confirmed after the British re-occupied Hong Kong four weeks later that they had damaged the cable so badly it didn’t function. Therefore, the mission was re-graded as a success.

Recognition

Shean left the Navy after the war and completed his engineering degree. He worked for the City of Perth Electricity and Gas Department and the State Electricity Commission until his retirement in 1978. He was awarded the American Bronze Star in March 1947 for commanding XE-4 under the successful Operation Sabre and died in 2009 at Perth.

Briggs was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on 18 November 1945 and, after the war, had a successful career with the British United Shoe Machinery Company in Perth as a mechanic. The pay was worse than the Navy, but he was promoted to branch manager shortly after. He retired to Brisbane and died in 2018.

Remarkable men and story.

Among the many who were women and men of perhaps the greatest generation.

A remarkable story that certainly needed to be told. Thankyou!