“By limiting access to a public space based on religious beliefs and a narrow definition of identity, the rights of those who do not fit these criteria are unequivocally violated. The park, funded by taxpayers and intended for the enjoyment of all, is being co-opted by a specific group, imposing their beliefs onto the general population”.

Philip Leitch

“Grand mountain peak, fair as the dawn Thine eyes alone envision first, Thou standeth there as thou were born. Thy sides still clothed with nodding trees; The crown is wrought with flow’ring gems, And kissed so softly by the breeze. Proud mount, forever wilt thou be A mighty monarch on thy throne; True king of all that thou canst see!” G. A. Laker, 1934

Introduction

Hard as you try, when travelling in the Tweed Valley or passing along the Pacific Highway (now Motorway), you cannot miss Mount Warning. It is a striking feature of the far north coast of New South Wales – the peak is bosomed in the skies!

Mount Warning offers the opportunity to see the morning sun first rise over the horizon on the Australian continent. The dominant mountain peak is visible from many points, which is unsurprising as it stands at 1,159 metres high and only 32 kilometres inland. Captain James Cook saw the mountain in 1770 as an important landmark after encountering dangerous shoals off the coast. He later wrote that mariners would always be able to know their position by this mountain, and he named it Mount Warning.

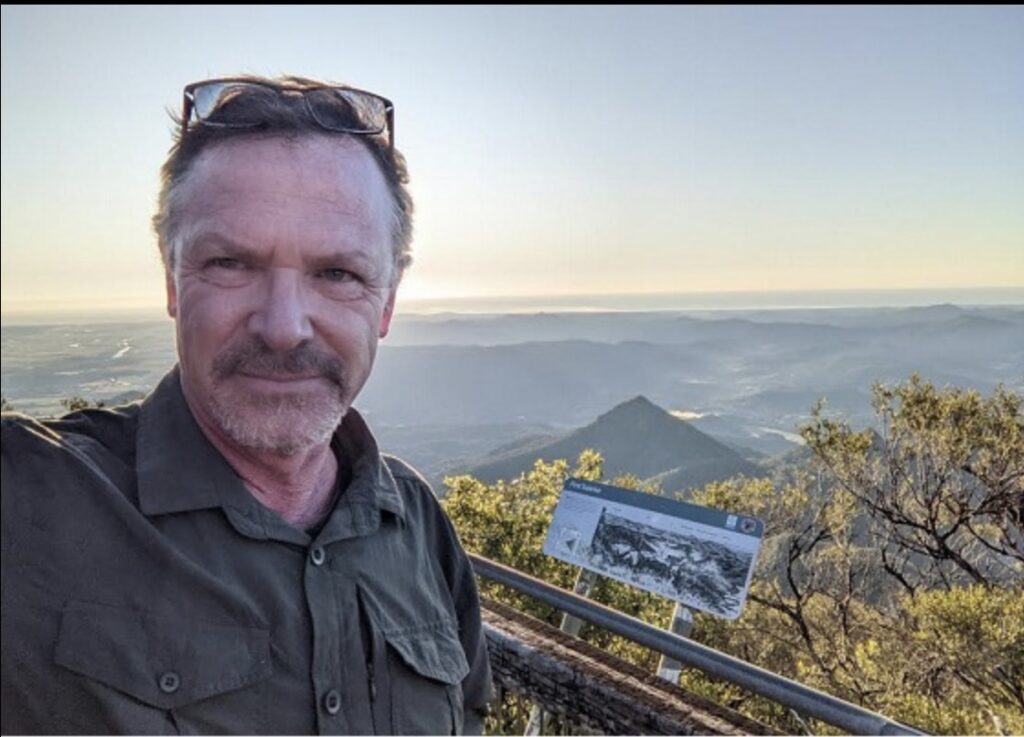

Watching the sunrise from the summit of Mount Warning. Photo Marc Hendrickx.

The mountain is a volcanic plug, the remains of the centre of a huge volcano active in the region 20 million years ago. The activity of that volcano created the landforms of the area surrounding Mount Warning, with the McPherson Range to the north forming the border with Queensland, the rim of that once-active volcano. Mount Warning is considered one of the best-preserved eroded shield volcanoes in the world, and international geologists have visited the site to learn about volcanic processes.

Locals and visitors have been climbing Mount Warning for over 100 years with the blessing of local Aboriginals with traditional links to the mountain. Until 2020, about 130,000 people climbed to the summit a year. But access to the mountain has become embroiled in a bitter fight between walkers and bureaucrats.

The official line is the walk will “remain closed pending the development of a Memorandum of Understanding and further joint management arrangements, with future management of the park to be guided by Aboriginal custodians”. However, that Memorandum of Understanding excludes the public.

Internal emails, forced to be released under a Freedom of Information application, reveal what looks like malfeasance on the part of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) because they have been secretly planning the closure of Mount Warning National Park prior to 2020, and have misled a minister in trying to achieve that aim. In addition, they have not been honest with the public.

History of climbing Mount Warning

In 1909, the New South Wales government made a grant of £300 for hand-cutting a bridle track up the side of Mount Warning. The 4.4-kilometre zig-zag trail has about 20 turns on a good grade until near the summit. The trail builders did a great job constructing dry stone walls and steps, allowing horses to climb the mountain to the last steep rock climb to the summit. Then there was a sharp climb over the rocks without chains to the summit for a magnificent view in all directions – the coast, the Tweed Valley, McPherson Range, Cunningham’s Gap and the Richmond Valley to the south.

However, by 1922, the bridle track was overgrown, preventing visitors from climbing the mountain. Several residents rallied to re-open the track and even fund the Council “maintenance man” to assist in the maintenance work on Saturday afternoons.

(Right) The stone work on the walking track to the summit has lasted over a hundred years. Photo Marc Hendrickx.

In 1924, a plaque bearing a section from Captain James Cook’s 1770 journal on how the mountain was named was put on the summit by a group of 80 schoolchildren from Murwillumbah.

In 1925, the local district forester recommended the dedication of 4,700 acres (1,900 hectares) as a national park. The national park was gazetted in July 1928, and an official opening ceremony, attended by 200 people, was held at the summit in August of the following year. Trustees from the local community initially managed the park.

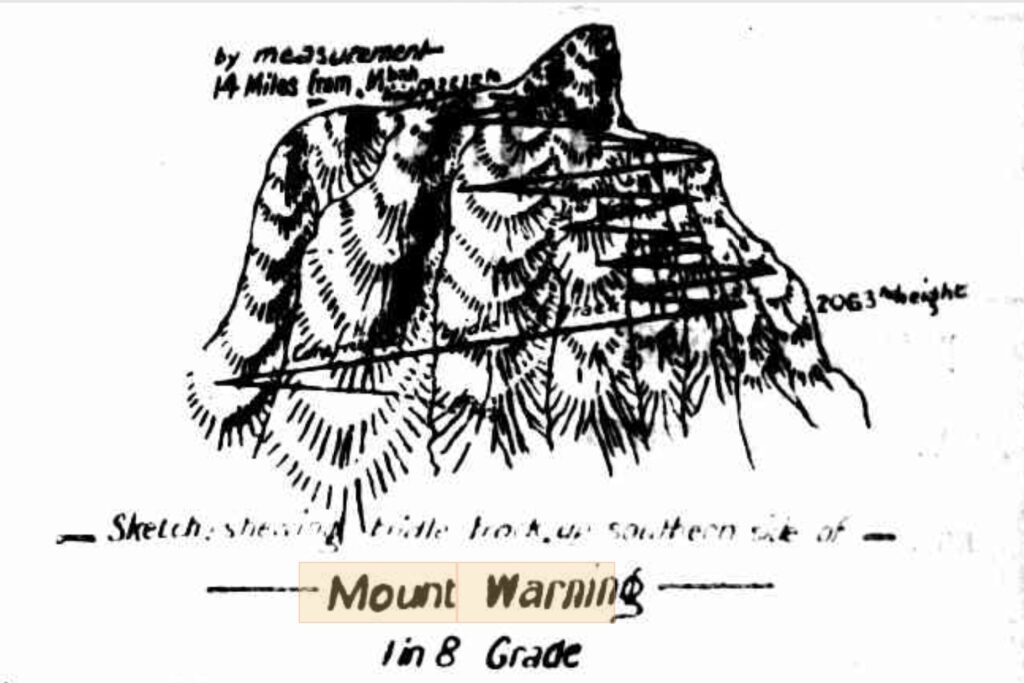

Sketch showing bridle track up the southern side of Mount Warning from 1925.

After the Trustees struggled to keep up with the required maintenance, the Tweed Shire Council took over management of the park in 1933. Undoubtedly, with the increasing visitor numbers, there was pressure on trail maintenance.

Over the years, the walk to the summit of Mount Warning gained a reputation as a must-see destination on the north coast. NPWS helped promote the hype by describing the hike as “fantastic…a steep climb and dazzling views” in brochures they produced in the late 1990s. The walking track and steep scramble to the summit have remained the same since 1909. The only change was a new viewing platform constructed in the late 1980s. However, as early as 2002, with the chains supported by steel posts still in place, NPWS suddenly changed their description of the walk to “long, steep, difficult and dangerous”, with the final rock scramble as a “very strenuous 100 metre vertical rock scramble”.

What makes the cultural significance of Mount Warning more critical than other equally significant areas?

The higher section of Mount Warning, 600 metres above sea level, was gazetted as an Aboriginal Place on 8 August 2014. The gazettal notice recognised eight different Aboriginal folklore stories about the mountain. The only problem is that NPWS have subsequently ignored seven of them and favoured just one. But more importantly, declaring an Aboriginal place doesn’t preclude existing activities. Rather, it is a formal means of recognising spiritual and cultural importance. For example, an Aboriginal Place exists over Bulahdelah Mountain and the public is still permitted access.

Bulahdelah Mountain.

Many other New South Wales mountains within national parks and conservation reserves have a deep Aboriginal spiritual connection and can still be climbed or visited. For example, there is Mount Canobolas. It towers over the central western plains of New South Wales, reaching 1,390m above sea level, with nothing higher in the country further west before reaching the Indian Ocean. It has recently had visitor infrastructure and walking tracks upgraded to support visitors enjoying the area. There is also a tourist drive to the summit that supports major telecommunications infrastructure.

Despite the European intrusion, the mountain retains its significance to local Aboriginals for important male initiation ceremonies. NPWS say this about Mount Canobolas in December 2022:

“The Mount Canobolas Summit, the highest peak in Central New South Wales, has recently re-opened following development work that has made the incredible site accessible for all to enjoy stunning views from the top, complete with a new lookout, accessible amenities and pathways, cultural interpretation and a visitor car park”.

New visitor facilities at the summit if Mount Canobolas.

Another popular mountain site is Mount Dromadery or Mount Gulaga. It is sacred to the Yuin people. Their story is that the mountain is their mother from whom they came. While the NPWS promote the mountain as sacred, the public can still climb it.

There are many other similar examples across the state.

So, what exactly makes Mount Warning different, and why is it now so crucial that Europeans are suddenly no longer allowed to climb it?

A pattern of bans creeping in around Australia

There is a disturbing trend of closures of public areas for dubious reasons, and Mount Warning seems to be captured in that trend. Some people have suggested that the closure of Mount Warning National Park is the tip of an iceberg and the first tentative step by the government and bureaucrats to prevent the public from accessing any of the state’s national parks in the state for enjoyment.

Unfortunately, Mount Warning isn’t the first national park where people are prevented from visiting to protect Aboriginal sites or for spiritual reasons. For example, one of Australia’s former iconic places to visit was Ayres Rock. In October 2019, Parks Australia imposed a permanent blanket climbing ban. A book by engineering geologist, Mark Hendrickx, titled A Guide to Climbing Ayres Rock, outlines how an unrepresentative minority of Aboriginals successfully blocked access to an icon that all Australians consider their own. The book prompted adventurer and environmentalist Dick Smith to call it “an important book on how hard-won freedoms of adventure are being whittled away”.

The author had this to say:

“…something as wonderful and awe inspiring as the simple act of walking up a hill in the middle of nowhere to look over magnificent views of the desert could be closed down by a bunch of weak kneed passionless politicians and dead hearted bureaucrats and a few self-fish land owners who have forgotten the wise words and actions of their elders – old men who graciously shared their home and their stories with many tourists and helped make the visit to Ayers Rock something magical. The reputation the Rock has gained as a place of wonder is partly due to these more enlightened custodians from the recent past who also climbed up their rock.”

In March 2022, the Victorian government banned over three-quarters of the world-famous rock climbs in the Grampians National Park. However, the ban soon extended to everyone, including walkers, before some activities were “allowed” under tightly controlled rules. Then, similar to Mount Warning, the government sneakily used the Covid pandemic to strike, introducing the required regulations “to manage risks to public safety related to Coronavirus (Covid-19)”. The Victorian state of emergency ended on 12 October 2022, yet the rules banning access supposedly for infectious disease control still remain in place.

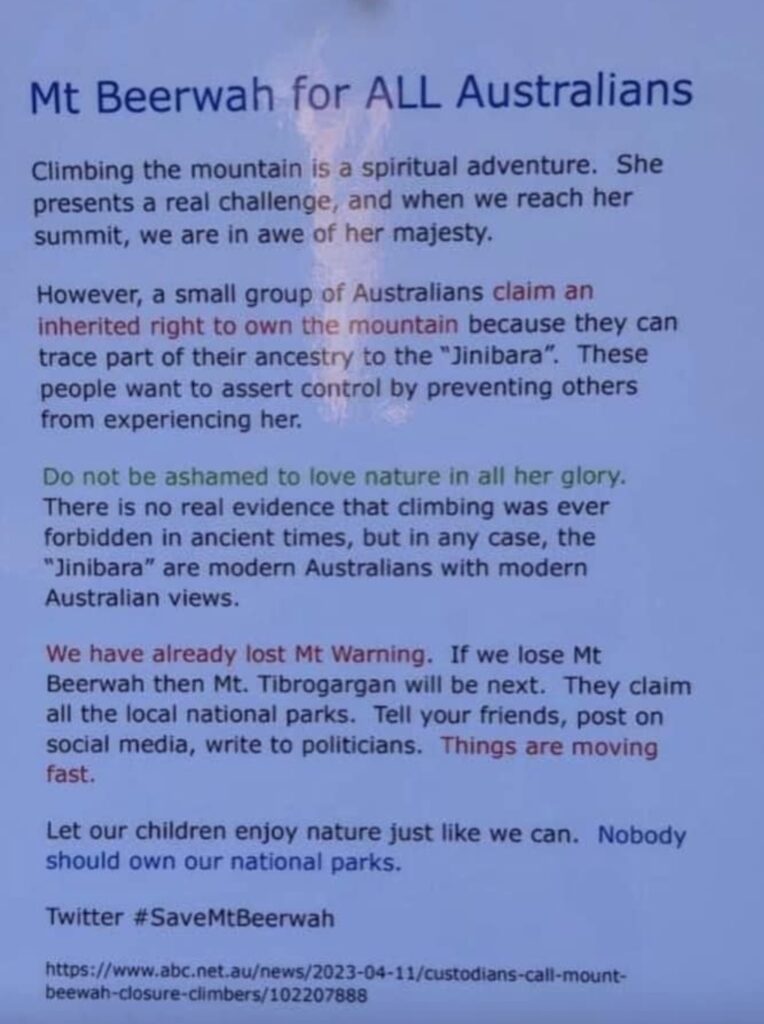

Recently, Aboriginals and the ABC have questioned continuing access to the iconic Mount Beerwah climb in the Glasshouse Mountains of south-east Queensland. Just last week the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) announced the temporary closure of Mount Beerwah until 5 June to allow for “cultural healing and reparations following vandalism on the Mountain”. Then a day later, their closure notice was changed to say the closure was until 9 July, despite the notice having the same issue date and time as the original one. The fact that someone used a grinder to carve a Christian message in a rock is hardly grounds to prevent access to the whole mountain. There are several tracks up the mountain where climbers can avoid the vandalised area while reparation works are carried out. Unfortunately, vandalism on the north-east route is common, has never required a period of “healing”, and is always repaired without the need to close the park and stop visitors climbing the mountain.

Another recent closure is Mount White in the Spring Mountain Conservation Estate by the Ipswich City Council in Queensland because it is now protected under the Aboriginal Cultural Act. “For public safety and cultural and environmental protection, this area is patrolled by officers of Ipswich City Council and the Queensland Police Service”, the sign says.

Locals in the small Queensland outback town of Camooweal have woken up to news their popular billabong camping site on the banks of the Georgina River, that draws hordes of tourists every winter, is now temporarily closed by the local council due to “concern the area’s Aboriginal heritage is being trampled on”. It now puts the popular Camooweal Drovers Festival in jeopardy as attendees will have nowhere to stay, other than the caravan park. Why was this decision made at the start of the tourist season?

The Camooweal decision follows the closure of the popular Bear Gully campground in Victoria in April after “advice that camping and recreational activities within the park may have impacted on Aboriginal place and its artefacts”. Parks Victoria have told the public they are taking “a precautionary approach”, as they deny campers the opportunity they always have of enjoying the beautiful remote beach area overlooking Wilsons Promontory. Beach access to the campsite is also blocked. Parks Victoria said the campground would be closed for a month until 7 May, however, according to its website it remains closed “until further notice”.

Are the safety and visitor concerns overplayed or fabricated?

The current restrictions at Mount Warning started in March 2017 when, after flood damage, the walking track was closed for a few months while NPWS carried out repairs and maintenance. It re-opened six months later but was closed for Covid on 30 March 2020 due to the nebulous concept that “hygiene risks involved in sharing a chain to scramble the final 100 metres of the summit trail”. The closure was due to end on 4 December 2020, but the national park has remained closed ever since.

NPWS have admitted that Tweed Murwillumbah Visitor Centre receives over 20 phone and counter enquiries daily, wanting to know when the Mount Warning walking track will be re-opened. In addition, many people have written to the minister objecting to the continued closure of the park.

The disgraceful state of the car park. NPWS stand guilty of deliberately allowing the facilities and walking track to be run down by carrying out no maintenance in the last ten years. Photo taken January 2021 by Marc Hendrickx.

The minister referred each of those letters to NPWS to respond. In each case, NPWS claimed, “the NSW Government has not decided to permanently close the Wollumbin summit track”. However, they have failed to tell the public they first hatched their plan to close Mount Warning many years ago and have persistently tried to get ministers to approve their plan.

They refer the public to an information brochure about the closure with vague references to safety, environmental and cultural concerns. However, while the park was closed due to Covid, NPWS organised a safety audit and an engineering inspection in August 2020. According to NPWS, the report “identified an extreme risk of failure of the chain section near the summit and recommended the track be closed within six months as the risk of further accidents or fatalities from a catastrophic failure is high”.

Hendrickx, who specialises in Landslide Risk Assessment, obtained a copy of the engineering report, which found that the post footings were an issue, but the chain and its connections were fine. Hendrickx recommended that NPWS carry out a comprehensive quantitative risk assessment. Regardless, NPWS took the opportunity to remove the posts and chain, despite no test to determine the surficial corrosion’s impact on the posts.

Very minor, surficial corrosion at base of posts after their removal by NPWS. Photo Marc Hendrickx.

Concrete footing after removal by NPWS. Where is the dangerous corrosion? Photo Marc Hendrickx.

Hendrickx climbed the summit on 4 January 2020 as a duty of care to ensure NPWS received fair geotechnical advice. He believes their assessment released to the public, and used by the minister, contained a multitude of errors. He took photos of the steel posts and footings after NPWS removed the posts and chain. His pictures (above) clearly show only superficial corrosion.

NPWS are also being disingenuous with their safety claims when they wrote to the minister:

“NPWS and NSW Police have responded to 44 significant visitor safety incidents on the Summit track over the past 10 years, including two deaths. These incidents have involved both heli-evacuations and search and rescue operations. The number of unreported injuries is likely much higher”.

However, the two deaths have nothing to do with climbing the steep section. One was due to a lightning strike at the summit that killed a backpacker in 2016. The second was in 2019 on the lower part of the walk, where an 80-year-old woman suffered a heart attack. There are numerous similar walks in the state’s national parks with much the same or worse sections than the summit section of Mount Warning. They have records of more incidents compared to Mount Warning; nevertheless, there are no plans to close those walks.

NPWS also refers to a visitor survey claiming, “there is a high level of community acceptance of the significance of Wollumbin Summit and the message not to climb”. However, NPWS won’t make the survey public. Is it because the survey was poorly designed, is of a limited extent, and is biased with loaded questions and misinformation that hide the context and mislead respondents, preventing them from making an informed response?

Emails obtained under Freedom of Information reveal the results of a separate Southern Cross University survey of walkers in 2018, which admitted that almost all visitors attempt to reach the summit (95.3 per cent) and most (87 per cent) achieve it. Furthermore, individual safety was a minor consideration of walkers, and significantly, only 2.1 per cent of walkers were deterred by the chains, steepness, and safety signage. This information directly contradicts what NPWS wrote to their minister in a briefing note obtained under Freedom of Information.

A better approach would be to have NPWS run a properly designed visitor survey of the 130,000 people who visit the summit each year to gauge the public’s view on climbing Mount Warning.

Is NPWS being truthful about Aboriginal cultural concerns?

After the declaration of the area of Mount Warning, 600 metres above sea level and higher, as an Aboriginal Place in 2014, NPWS prepared a draft management plan in 2020 and implemented it secretly, despite being a draft. The plan states:

“…access to the Wollumbin Summit must be restricted and there are no conditions under which public access could be consistent with the cultural values. Public access is not culturally appropriate”.

What is disturbing is that after 100 years of walking to the summit, suddenly, according to NPWS, visitors are harming the cultural values. NPWS claims the summit is a “sacred place of the highest significance to Bundjalung people and other Aboriginal Nations”. They state they have consulted with the Aboriginal community through the Wollumbin Consultative Group since November 2000. However, it is strongly disputed that a Bundjalung nation ever existed, and is more a government-created entity, as is the secretive Wollumbin Consultative Group.

The management plan they and NPWS developed seeks to ban public access and impose “male only” indigenous gender restrictions because the mountain is a “male initiation site”. This new cultural significance is promoted by the Bundjalung people, whose cultural links to Mount Warning are under question from both within the Aboriginal community and outside.

The reference to a male initiation site does not make any sense. A record of a climb up the mountain by Europeans in the early 1870s did not mention pre-existing trails to the summit, which surely would have been present if the summit area had been used as a male initiation site.

Drawing of Mount Warning, 1873.

NPWS also insist on calling Mount Warning Wollumbin. However, Wulambiny Momoli (‘scrub turkey nest’) is the correct traditional name for Mount Warning. Until 2000, the welcome sign to the park referred to Wulambiny Momoli, stating it was the name given by the original custodians, the Ngarakwal Githabul tribes. The dual name of Wollumbin was introduced only recently, in 2005. How can the traditional recognised name suddenly change without any Federal Court determination or formal process?

NPWS have done very little consultation in recent times, as part of the decision to ban walking based on Aboriginal spiritual grounds. This is in contrast to the 1970s and 80s, where they undertook extensive anthropological research across the state. Howard Creamer was the anthropologist assigned to cover the Mount Warning area and conducted field research between 1973 and 1987. During his interview with Millie Boyd, the Aboriginal name for Mount Warning was revealed as Walumbiny Momoli, not Wollumbin. The profile of Mt Warning from the north, clearly reveals the turkey sitting on its nest. It is this view that inspired the story.

Creamer is very disappointed with the current management of NPWS, none of whom have sought his views:

“I can confirm that during my field research with Aboriginal elders in the Northern Rivers, Northern Border Ranges and Tweed Valley areas from 1973 to 1987, I did not hear them ask that the walk to the summit of Mount Warning be closed. I am also disappointed that neither NPWS or Heritage NSW (local, region or head office), never asked me for my views on this matter. I am still around and these days I am active in cultural heritage repatriation of my work to local Aboriginal communities across New South Wales”.

The Wollumbin Consultative Group also recommend further cultural assessment toward a declaration and re-gazettal of all the National Park as an Aboriginal Place due “to the multitude of Aboriginal sites and the high cultural significance of all of the area within the reserve”.

According to Stellar Starlore, the Aboriginals dealing with NPWS do not represent any Federal Court-determined bloodline to country descendants from the original Yoocum Yoocum moiety. So it begs the question, exactly who are these people dictating sensitivities of an Aboriginal culture centred around Mount Warning?

NPWS refuse to disclose who the Wollumbin Consultative Group members are. They state it is, “due to the threatening nature of some correspondence received on this issue”. Despite many efforts to contact and speak with members of the Wollumbin Consultative Group by people from the “Re-open Mt Warning” Facebook page and a number of journalists, no one has been successful. As a result, they are an uncontactable, unregistered group of nameless people.

Dr Peter Solomon also disputes cultural significance claims made by NPWS. After years of study in the 1950s, his findings were published as a thesis for the University of Queensland. He looked for sacred sites and concluded that there were none around. “I certainly don’t think there is enough evidence that it [Mount Warning] should be closed off to everybody because of the presence of any sacred sites”, he said.

Local archaeologist Miss M. J. Martin wrote a story in 1947 stating the Tweed River Valley Aboriginal peoples were part of the Yukumbal tribe. In the upper valley of the Tweed River were the grounds of a small group known as the Wollumbin and Chinningum People, taking their name from the great peak they called Wollumbin.

Elizabeth Boyd is the authorised representative of the Ngarakwal Githabul women who are the totemic lore keepers of her people’s Bootheram (dreaming) and the original custodians of Mount Warning. She is the living Gulgan, inheriting responsibility for the traditional lores and customs of the moiety – the Yoocum Yoocum – from her mother, Marlene Boyd, who inherited it from her mother, Millie Boyd. In addition, she is the keeper of the old-world lore centred around Mount Warning – Grandmother Rainbow Serpent and Seven Sisters.

A sign on the summit of Mount Warning says it all. Photo Marc Hendrickx.

Marlene Boyd has publicly said she had no problem with people climbing the mountain. In 2007, not long before her death, she challenged the Bundjalung claims and stated:

“I do not oppose the public climbing Mount Warning – how can the public experience the spiritual significance of this land if they do not climb the summit and witness creation!”

She was distressed about the new-world Bundjalung’s claims that Mount Warning was a men’s site and their push to close the national park. Elizabeth believes this is significantly damaging their ancestral culture, tradition and lores. But what is shameful, is this important cultural group, with proven links to the mountain and its stories acknowledged by NPWS in the past, has been ignored for the past 20 years by current NPWS bureaucrats. NPWS have, and continue to, mislead the public about the nature of Aboriginal beliefs about the mountain.

The Ngarakwal Githabul women have not been included in any consultative process regarding the closure of Mount Warning, including the studies by Southern Cross University and NPWS, and have not been part of the Wollumbin Consultative Group. Why is NPWS ignoring the recognised traditional lore keepers of Mount Warning?

The dual naming of Mount Warning as Wollumbin and claims by Bundjalung groups that Mt Warning should not be open to the public are under contention. Marlene said, “Mt Warning is not the Fighting Chief as the Bundjalung claim”.

The New South Wales Government and bureaucracy stand accused of adopting a segregational policy that excludes non-Aboriginal and female Aboriginal visitors. In doing so, they have allowed the walking track to fall into a state of disrepair, further bolstering their claim that the park is unsafe to visit.

Is it too late?

In June last year, the Liberal government announced plans to hand over control of all the national parks to Aboriginal groups that live nearby. The former Minister for Environment and Heritage, James Griffin and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Tourism, Ben Franklin, jointly released the Wollumbin Aboriginal Place Management Plan that covers Mount Warning National Park.

Car stickers available to the public to show support for the continued access of Mount Warning for all people.

The management plan outlines the intent of the government to ignore dissenting Aboriginal voices, the forced closure of the park to the public, the banning of public access to the park under the threat of $550,000 fines, and the removal of all traces of European culture such as the summit lookout, helipads and the important geodetic survey markers. The plan even allows for the copyrighting of any images of Mount Warning, meaning the public cannot publish a photo of the mountain without the permission of the local Aboriginal people and the NPWS.

In essence, NPWS have achieved their long-held plans to shut down the use of, and access to, a national park on questionable grounds, based on the say of an unrepresentative indigenous group whose tribal links are contested.

The internal documents released under Freedom of Information reveal NPWS has no intention of re-opening Mount Warning National Park to the public. Furthermore, NPWS heavily redacted most of the documents they released, indicating they have something to hide from the public. They arrogantly believe running a public asset should be carried out secretly.

What wasn’t redacted revealed that bureaucrats started covertly scheming to close Mount Warning to the public much earlier than 2020. They provided misleading information to the minister to pressure the government to agree to their secret plans.

On 16 December 2022, the Wollumbin Stakeholders Advisory Committee held its first meeting. The committee includes representatives of local government and the tourism industry. Sadly, it appears Advisory Committee members have been coerced into following the narrative established by NPWS that the summit is an important Aboriginal place and must be off-limits, despite no consultation whatsoever with the public. The Advisory Committee have completely ignored the existing well-built track of heritage status designed and constructed a century ago. However, since the committee has no public representative supporting the walk, it is doing nothing to resolve the outstanding issues.

NPWS is spending $7 million of taxpayer funds to try and direct visitors to other walks in the Tweed Valley as an alternate Mount Warning experience. They include a walk on the northern flank of Mount Warning National Park to a lower area that looks across the mountain to the summit, called Caldera Rim track, despite not reaching anywhere near the rim of the caldera. Members of the popular “Re-open Mount Warning” Facebook page find this alternate proposal totally unacceptable.

Any decision as important as suddenly preventing access to Mount Warning, which remains a public asset managed by a public agency, must be conducted openly and transparently. The claim by NPWS that the presence of someone, based on race, could amount to desecration of an Aboriginal Place is absurd. As a colleague wrote, “the act of earmarking certain individuals as inherently defiling solely based on characteristics they cannot control is against the broader principles of exactly what desecration means”.

What is at stake is not a lack of respect for indigenous beliefs, but a new law and order that supports the selective prohibition to enter a public space based on race and beliefs. NPWS have decided that a small section of the indigenous community are the only ones that have a deep spiritual connection with Mount Warning.

The performance of NPWS thus far does not give the public any confidence that the right decision is being made. It also raises questions about the conduct of the agency itself, and its actions in this matter need to be independently scrutinised.

Last Word

I originally included a photo of climbers to the summit when the park was closed with this caption:

In the true spirit of reconciliation and looking towards a brighter future for all Australians, a small group of seven walkers climbed the summit of Mount Warning on Australia Day, 2023. They had the blessing of of Ngarkwal custodian Eelemarni Elizabeth Davis Boyd and was reported in the media. At her request they played a song from the summit about the mountains west of Mount Warning sung by her grandmother, Millie Boyd in the hope that this magical song would influence the Aboriginal men responsible for the closure, and help them support the women in sharing the mountain with everyone.

However, last May, NPWS served a legal demand on one of the climbers to attend an interview with authorised officers. She is accused of “unauthorised entry resulting in the desecration of the Aboriginal cultural and spiritual values”. Failure to comply with the notice risks a $250,000 fine. NPWS have resorted to heavy-handed “lawfare” to try and shut down public debate about access to the mountain, and it is for this reason I decided to pull the picture to avoid exposing the climbers to further unnecessary threats of harassment by bureaucrats. NPWS are attempting to silence any protest. It is nothing less than a form of nefarious bullying, and the new government needs to reign in these bureaucrats.

Also, in a bizarre set of circumstances, taxpayers are funding security guards to monitor the Mount Warning car park to prevent many visitors, who turn up on glorious days, from climbing the mountain. In the middle of the school holidays earlier this year, when tourists flocked to the popular far north coast, and the Gold Coast, they found out they could no longer experience one of the premier tourist sites of the region. We suddenly have a national park where no one is allowed to access it, unless you’re a male Aboriginal from the “Bundjalung” tribe, or a NPWS employee.

In response to letters to the Minister, NPWS maintains they, “will continue to engage with local stakeholders and the community through consultation as part of the future planning process”. Except, they refuse to answer specific questions and queries the community raise about the closure of the park. They simply respond with a bureaucratic template that is mumbo jumbo and gobbledygook. They refuse to consider Marc Hendrickx’s detailed complaints about the closure of the park, falsely claiming they have addressed his concerns. They have placed contact restrictions on him, telling him, “that you are not permitted to email complaints@dpie.nsw.gov.au or any other direct email as per the contact restrictions placed on you”.

It is clear NPWS do not like the public raising legitimate questions about the less than transparent way they have stopped walkers climbing the mountain and will only engage with sections of the community supportive of their stance and who they choose to deal with. If they truly claim to engage with everyone then at the very least, a representative of the “Re-open Mount Warning” Facebook group and the Ngarakwal Githabul women must be included on the Wollumbin Consultative Group immediately.

(Left) Marc Hendrickx on the summit of Mount Warning. Photo Marc Hendrickx.

I will finish with the words of Hendrickx:

“What was once billed internationally as a magnificent walk to witness the first sunrise in Australia will soon be the exclusive property of a small group of disgruntled activists who, like Tolkien’s Gollum, want to keep ‘the precious’ for themselves. If this is a taste of things to come, the public will no longer have any National Parks in New South Wales to enjoy”.

For further detailed evidence of NPWS behaviour, to view emails and documents released under Freedom of Information, the shoddy internal “review” by the Ombudsman, and the strong evidence of the exclusion of traditional custodians in decision-making in favour of a contested group of Aboriginals, go to Hendrickx’s web page and read his blogs.

If you agree that Mount Warning should remain open for the public to climb, and to keep up to date with news on Mount Warning and other mountain climbs, join the Re-open Mount Warning Facebook page and write to the Minister Penny Sharpe via the contact form at this link https://www.nsw.gov.au/nsw-government/ministers/minister-environment-heritage.

Wonderful detailed summary. Thankyou for writing this Robert.

Thanks for a great representation. I will copy the web page address to my facebook page and hope that readers will act. I tried to use the email addresses shown for the dpie but seem to have a problem.

Well done Warwick – we all need to stand up against this behaviour.

This could well be Australia’s defining white Mabo decision. Let the High Court decide.

I have strong religion with this mountain and I, an Australian, am cut off from going there.

Going to work I pay taxes to fund the closing of places.

While certain groups are given tax payer money to lobby and media push their closure agendas.

I hate what this country has become.

Thanks so much for such an extensive report of what’s happened to date.

It’s worth noting that the Boyd family and Ngaraakwal have been fending off Bundjalung groups coming after this mountain since the late 1990’s. Fletcher Roberts, an esteemed Lismore Elder issued a press release in 2000 saying the push to ban climbing on Mt Warning was ‘a modern day invention.’ He warned Bundjalung that there would be ‘cultural consequences’ for anyone ‘overstepping their cultural responsibilities’ making false claims on land outside of their boundaries.

The first claim to ban climbing was made by one of Fletcher’s relatives of whom he said ‘his knowledge about the mountain came from the very Elder who raised me and gave me my knowledge but he never told me not to go to Mt Warning.’ Bundjalung ignored one of their most esteemed Elders and have continued to ignore old lore risking the health and wellbeing of themselves and their families in pursuit of monetary gain.

The two stories Bundjalung cooked up especially to close/steal the mountain are easily disproved by Ngaraakwal, but NPWS have been stuffing us around for 5 months procrastinating about a meeting with us, them and the WCG members responsible for the lies.

The most ridiculous of the two claims is that the summit was used for initiation ceremonies. Ngaraakwal Elder Sturt Davis has first hand knowledge of this ritual in WA and he says since there were no helicopters back in the Dreamtime the initiates would have needed to be carried off that mountain. The traditional men’s site for Ngaraakwal initiations is miles away from Mt Warning and it is most definitely not on the top of a mountain!

Like Gitabul (Urbenville) and Bandjalang (Coraki, Box Ridge) Ngaraakwal do not identify as Bundjalung.

Great article summing up history of this magnificent mountain including the latest on NPWS heavy handed actions. Thank you !!

Well done, thoughtful, sensitive and logical – all qualities seemingly lacking in our bureaucrats and chip-on-shoulder activists.

Very well researched Robert. Thanks for taking the time to write this.

Thanks Robert. First class research, well-argued and well written. I hope you are able to bring the article to the attention of the Minister and the CEO of NSW P&W. Quite apart from the Mt Warning situation, you are alerting all Australians to a new trend – closing national parks for recreational use.

Aboriginal heritage is only one factor. There is, another reason underlying all this. When I first became involved in national park management in WA in 1985, I was astounded by the antipathy towards park visitors and tourists (always referred to by ranger staff as “terrorists”) by many in the National Parks Authority.

I used to call it the Basil Fawlty Syndrome. Basil, you will recall, used to say he could run a really good hotel if it wasn’t for the guests. I suspect that what you are seeing at Mt Warning also has a sniff of Basil Fawlty Syndrome about it. Any excuse will be used (including Covid) to limit national park access to visitors and tourists. Your photo of the car park was revealing.

Living in WA, I have almost no experience with NSW parks, but I did once (not long after the Black Saturday fires) attend a meeting in Canberra to discuss the national bushfire threat and the need for improved bushfire management. I was flummoxed when the representative of NSW P&W stood up and denied there was a bushfire problem at all in NSW’s national parks, and he didn’t know what all the fuss was about. This told me all I needed to know about the leadership and nous of this organisation.

Kind regards, Roger

If we are allowed to visit, will we have to pay to visit these places?

Where will it end?

Thanks for presenting the case for reopening access to Mt Warning in such a clear compelling manner, that only the blind, or the NSW National Parks Service could fail to acknowledge it.

Thanks for providing your context of the Mt Warning discussion.

Surely this is a clear violation of the RACIAL DESCRIMINATION ACT.

It works both ways and the aboriginals are obviously in breach, by denying white people access, with the act in part specifying “and accessing public places”.

This legal avenue needs to be pursued, as I thought we were ALL AUSTRALIANS TOGETHER.

Obviously, the people making these decisions are too stupid to see that decisions like this, are only “widening the gap” and creating racial tension.

Well said. 100%, and where are all our human rights? We need a lawyer to do a class action against the Aboriginal parties involved and NPSW. It’s criminal what they have done in Australia, banning us mixed-race people.

Stuffing around with bureaucrats will take forever and will get you nowhere, these people are true dictators and you will find that with most public servants, they will never let go of the little power they have.

This illegal closure needs to be challenged in the NSW high court. Has anyone proposed this?

I suggest a lot of people would support this.

It is so sad to read this and for all Australian’s indigenous residents and visitors to the region.

I just can’t understand how the closure of a climb to the summit of this iconic peak would reconcile, foster empathy and inspire compassion for any individuals desire or belief related to this natural wonder.

It’s clearly divisive and rallying people otherwise on the side of the environment, conservation, social equity, racial equality and reconciliation.

A brilliant summary about the hypocritical actions of a small minded, local Government, trying to close a Australian Landmark down, in order to appease a minority over and above the broader majority of all Australians, that like to share and enjoy all our Nature provided heritage, in the short time we walk on this earth.

Those depriving another of the pleasure ought to know, that their sadistic and cruel measures, will effectively only contribute to more hatred and division instead of bringing people together in unity to move together forward as ONE People.

Remember, any human on this Earth, is indigenous to a certain part of land on this planet, yet that in turn, is not a right of ownership of any kind, as we belong to the land, not the other way round and need to share the experience regardless of skin color or creed.

Another example of a group of NSW so-called public servants, who totally ignore their obligations under Section 7 of the Government Sector Employment Act 2013. See below. Why do bureaucrats in the NSW NP&WS and environment agencies seem to be able to ignore core requirements of their employment and never be held to account by agency CEOs and a growing list of incompetent ministers?

The 7 Government sector core values:

The core values for the government sector and the principles that guide their implementation are as follows–

(a) Consider people equally without prejudice or favour.

(b) Act professionally with honesty, consistency and impartiality.

(c) Take responsibility for situations, showing leadership and courage.

(d) Place the public interest over personal interest.

(a) Appreciate difference and welcome learning from others.

(b) Build relationships based on mutual respect.

(c) Uphold the law, institutions of government and democratic principles.

(d) Communicate intentions clearly and invite teamwork and collaboration.

(e) Provide apolitical and non-partisan advice.

(a) Provide services fairly with a focus on customer needs.

(b) Be flexible, innovative and reliable in service delivery.

(c) Engage with the not-for-profit and business sectors to develop and implement service solutions.

(d) Focus on quality while maximising service delivery.

(a) Recruit and promote employees on merit.

(b) Take responsibility for decisions and actions.

(c) Provide transparency to enable public scrutiny.

(d) Observe standards for safety.

(e) Be fiscally responsible and focus on efficient, effective and prudent use of resources.

Thank you for all you are doing in representing “The Silent Majority”.

This is not just about Mt. Warning, but in principle, about all the other sites around Australia that we are having stolen.

Thanks again, Dane Snelling.

P.S. I am not in a strong financial position, but if you need or have a way of accepting contributions to the cause, please advise.

I recall climbing the mountain at sunrise in the spring of 2016. I camped at the Mt Warning campgrounds.

Upon return to the campground, an indigenous man was there doing paintings, sitting at the picnic table area. He was also selling the paintings. I had a chat with him. He was very verbally aggressive about that, “one day soon, this mountain will be closed to people like you”.

He divulged he was heading up a group to ban the climbing of Mt Warning as it was a ‘sacred site’. He arrogantly told me he doesn’t have a driver’s licence as he doesn’t recognise the laws of white people. All the while making a living out of selling paintings to tourists, wearing white people’s clothes, illegally using white people’s infrastructure (roads), driving white people’s technology, eating the food, using the facilities and the list goes on.

The conversation could have gotten heated for obvious reasons, but I knew to play it straight. He was an arrogant man.

It was a conversation I never forgot. So when I learnt of the closure of Mt Warning, I always think of this man!