In September 1939, at the start of World War II, Japan was embroiled in its invasion of China, and Australia committed its troops overseas to help Britain. By early 1941, Australia had sent three infantry divisions and substantial air and naval resources to the Mediterranean and European theatres. Thus, in December 1941, when Japan entered the war against the Allies, much of Australia’s armed forces were heavily involved in campaigns far from home. Australia faced the potential of an invasion without its troops to defend it.

The government and military chiefs never lost sight of the Japanese threat. Accordingly, they sent the 8th Division, several Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) squadrons and warships of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) to Malaya, with others in the Australian territories of Papua and New Guinea, and more ready to follow to the Netherland East Indies (modern Indonesia). Yet these moves were token gestures, particularly without huge supporting commitments to those areas from Britain or the United States.

Preparing for an invasion of Australia started in the early 1930s. Then, most of the civil defence functions were under the state governments’ control. It meant there was a marked difference in policy and practice across the country, despite the role of the Commonwealth in coordinating efforts across the nation.

While Tasmania was geographically isolated, it was fairly insulated from any impacts of the war than most other parts of mainland Australia. However, a sense of vulnerability to attack was elevated when enemy mines were found near the Derwent River entrance, and a Japanese submarine-launched seaplane flew a reconnaissance mission over Hobart in March 1942.

For these reasons, Tasmanians joined the rest of the country in preparing for a potential raid or invasion. Local police divisions were used as the nucleus for air raid precautions. A “Ways and Means Committee” had been set up in 1938 to provide training within the police force, but it became too big a task for them when the civil population was included.

In March 1939, the Civil Defence Legion (CDL) was created, first in Hobart and then in Launceston under the Civil Defence (Emergency Powers) Act 1939. Sections were related to government departments or utilities. For example, the Commissioner of Police looked after enlistment and warning alarms, and Hydro Electric Commission headed the team on light and power. In November 1941, the CDL was reorganised with zones and zone control, as in England, under a State Control Centre.

CDL Warden Badge

The Air Raid Precaution arrangements were developed in most states like those adopted in England. Civilian Wardens and chief wardens oversaw posts, usually set up at railway stations, town halls or schools. Emphasis was first placed on gas but later saw precautions against high-explosive and incendiary bombs. Control of lighting was also planned, types of shelters discussed, and air raid warning systems installed.

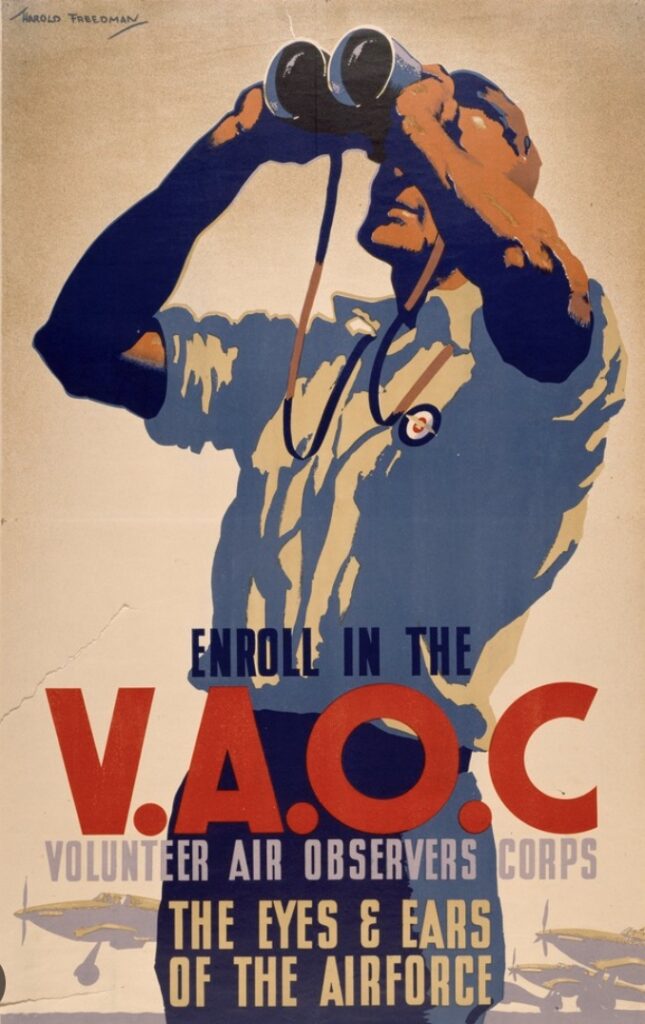

The Volunteer Air Observer Corps was on duty at about 2,800 observation posts around the country. All aircraft heard or seen were reported to the Royal Australian Air Force to monitor their movements and enable them to be aided if in distress.

Each city or town in Tasmania had a principal civil defence officer. Generally, Tasmania was considered in good shape to deal with any emergencies. After visiting the state in 1940 and seeing field exercises carried out, the Commonwealth Director of Civilian Defence and State Cooperation, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Thirkell, believed Tasmania could, “with short, intensified training and if issued with equipment,” be expected to deal with an emergency.

(Right) Poster encouraging civilians to participate in the Volunteer Air Observer Corps.

When adopting suitable lighting and blackouts for air raid precautions, the problems were complex. Tasmania was seen as having a low level of attractiveness for any Japanese strategic interests. Only Hobart and Waddamana were listed as vulnerable places. The latter is because of the dependence on hydroelectric power.

The main effect on Tasmanians was the emphasis on controlled or restricted lighting and blackouts after an air raid warning. It involved the prohibition of non-essential lights, reduction of essential lights, arrangements to put out lights, and fitting screens to vehicle lights. A blackout would involve the extinction of all exterior lighting and all light emitted from buildings, including houses.

All windows wore blackout curtains—wardens patrolled to check that there were no lights to be seen from the outside of buildings, especially during night-time Air Raid Drills, when the eerie sirens would sound. It was believed that if there were no lights showing, then predatory night bombers would pass over towns without any threat. State Library of Victoria Argus newspaper collection H99.201/4013.

After Japan entered the war, the premiers of each state were authorised to direct any total or partial black-out and to prohibit or regulate the display of lights in their state. For Tasmania, Launceston was added to the vulnerable sites list. Still, because the Commonwealth deemed all areas within ten miles of the coast and all towns within 100 miles of the coast required restricted lighting, many more places were affected.

For the north-west coast and Surrey Hills, the tiny settlements of Waratah, Guildford, and Parrawe suddenly saw themselves having to comply with the strict wartime restrictions. It meant that while individuals were not required to build shelters in their backyards, they “should not be discouraged”. Private persons had to bear the cost of their shelters, and the government funded the cost of shared shelters. For Guildford and Parrawe, no shelters were built. Perhaps the risk was seen as minimal.

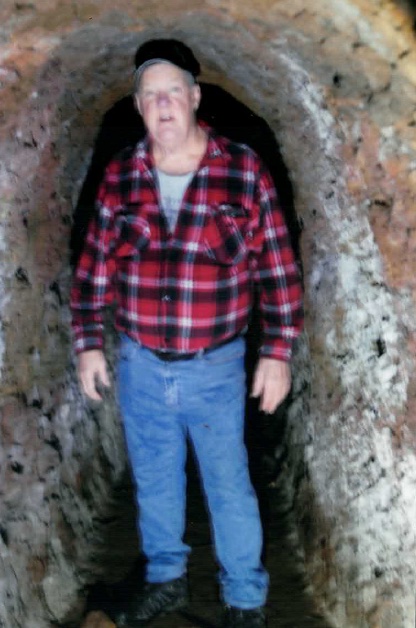

(Left) Mott Ryan inside the explosives magazine tunnel near Guildford. Photo courtesy Mott Ryan.

According to Mott Ryan, an underground magazine tunnel was built south of Guildford adjoining the railway line to house explosives for the construction of the railway to the west coast in the late 1890s and early 1900s. However, it wasn’t used as an air raid shelter, probably because it was too small and too far from the town, or quite simply the residents of Guildford didn’t think it was necessary.

Boys from Sydney’s Church of Grammar School perform an air raid drill in 1942. State Library of Victoria Argus newspaper collection. H99.201/4024.

The threat of enemy attack on Tasmanian soil during WWII was thought unlikely. However, once the perceived threat rose, thousands signed up for the State’s CDL.

One of the defining events of the war that reinforced Australia’s vulnerability not far from Tasmania occurred on the night of 31 May 1942. Three Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney Harbour, intending to damage Allied warships. Their brazen attack initiated a Japanese submarine campaign in eastern Australian coastal waters.

The air raid wardens’ service was officially established, and the government brought the CDL under wartime regulations. Consequently, Tasmania trialled a total blackout at night.

In July 1942, Frank Burridge was appointed section warden at Guildford and was assisted by Charlie Wilson as the special constable. Similar arrangements and appointments were made for Waratah and Parrawe. Their primary duty was to control lighting by residents to ensure they abided by the lighting regulations.

Charlie’s son, Lloyd recalls all doors and windows of the 20 or so houses were required to be covered with heavy dark material or curtains which would not allow rays of light to escape, which could be seen by enemy aircraft. His father, wearing the CDL armband, had to ensure everyone complied.

Nearby, Waratah held several Air Raid Precaution rehearsals. A total blackout was enforced between 9:30-10:30 pm on 9 February 1942. The CDL expected all residents to observe the regulations by adequately screening windows. At Burnie, volunteers constructed trenches lined with timber to protect school children in the event of an air raid.

There were also daylight air aid rehearsals which involved a series of long blasts on a siren at an undisclosed time, and all CDL personnel were required to report for duty at their allotted stations. Members of the public had to take shelter immediately after CDL sounded the siren and the streets were to be cleared of people.

(Left) Schoolchildren in a trench. AWM 011522.

For Guildford, Margaret Brown (nee Burridge), who was seven years old, remembers a similar trench built in the schoolyard, except it wasn’t lined with timber. The schoolchildren had to jump into the shallow dirt trench when instructed. It was all a bit of fun as they were never told why, except what to do if planes were overhead.

By October 1942, the CDL had 13,793 registered civilians. It was the peak period of the state’s readiness for an attack.

On 7 November 1942, a daylight emergency practice was held throughout the state. The exercise tested communications between the three fighting services and the CDL. When they heard the air raid warning signals, the public had to take shelter.

(Right) Hospital ship the Centaur. AWM 043235.

The rehearsals and restrictions continued through 1943, as the Japanese renewed their submarine offensive in Australian waters. By June, they had attacked twenty-one ships and sunk eleven between Cairns and Gabo Island. When the hospital ship the Centaur was sunk on 14 May, the 268 lives lost with it represented the most significant loss from a Japanese torpedo in Australian waters. Though brightly lit and adequately marked as a hospital ship under the Geneva Convention, it was hit at 4 am off Brisbane in clear weather.

Fortunately, the situation didn’t get worse for Australia. Prime Minister Curtin announced publicly, in June 1943, that the danger of invasion had passed. Nevertheless, many of the defensive measures at home continued to operate – for example, three infantry brigades and 32,000 troops in the Northern Territory at the end of 1943. During 1944, the restrictions were gradually reduced as the war improved for the Allies and were removed in September 1944.

To mark the end of war hostilities, most, if not all, towns, including Waratah, Guildford and Parrawe, held large celebrations. Life then returned to normal in the isolated, small towns on or near Surrey Hills.

Top article Robert. Well researched and a great read.

A great article Robert. There was certainly a lot of information there that I was unaware of. I enjoyed the read.