Introduction

This month marks the 55th anniversary of the worst fires experienced in the Bellinger Valley since European settlement. The late spring and early summer of 1968 was one of the worst fire seasons experienced in New South Wales. Spring was exceptionally dry in coastal areas, with Sydney only receiving 29.5 mm for the season, easily the driest on record. 1968 was the driest year for the state in the 20th century. Coffs Harbour only received 1,140 millimetres of rain for the year, which was 500 millimetres below average. It was so dry there were more flying foxes seen than normal as they were desperately trying to find food, raiding fruit trees and banana plantations.

After years of drought, the whole state was a tinderbox. Fires burnt out of control along the eastern seaboard from near Bega to Bundaberg in Queensland. International expert on fire behaviour and management, Phil Cheney, recalls flying in a light aircraft from Bega to Singleton in the Hunter Valley following the fire edge line that was broken only in three places. Many of the fires were lit in the late winter and usually went out in the evening or were extinguished by rain. However, the drought conditions from the previous summer persisted, and the fires reached a size under adverse weather conditions that made them virtually impossible to control.

There have been many disastrous bushfire years in the state. Still, the spring of 1968 was remarkable for the number of fronts of great magnitude that occurred almost simultaneously over an extensive area of the state. Between 27 October and 1 December that year, 14 lives were lost, and many houses were destroyed, including 161 in the Sydney suburbs, burning almost two million hectares. The disaster happened only 20 months after the Hobart tragedy. A highlight was that property damage sustained in suburban areas of Sydney, Illawarra and the Blue Mountains resulted from fires which originated a considerable distance from habitation and burned for several weeks before they entered the suburbs under “blow up” conditions. In terms of its duration, area burnt and contribution of drought conditions, only the recent 2019-20 fire disasters can match that with a higher death toll for the state.

The threat was so significant that on 29 October 1968, the New South Wales Legislative Assembly passed a motion of urgency to suspend standing orders. The afternoon session was devoted entirely to discussing bushfire problems.

Remarkably, and particularly on the north coast, the 1968 fires have disappeared from the consciousness of people’s minds and memories. There is little record of the fires. The memories of those who lost their lives are all but forgotten. The only way to relive the carnage is through scattered reports in the local newspapers.

The south coast fires

In June 1968, fires started to cause problems around Eden. For the south coast, this was highly unusual as fire danger is not usually a problem at that time of the year. Fuel was very dry after three years of below-average rainfall. Between 16 and 30 September, nine fires burnt from Central Tilba to Ulladulla, with four significant fires starting in one week.

The Yourie Gap fire started in the same area as the 1951-52 Bega fire. It was an escape from burning off on the tablelands near the Tuross and Back River junction. It raced in a south-east direction across Wadbilliga and Murrabrine Trigs. Luckily, the central fire front passed through an area that had been control burnt five months earlier. Eventually, however, the slow-moving fire was outflanked some days later and headed towards the Bega Valley farmlands, where firefighters finally controlled it.

The Woila Creek fire began on 12 September near the junction of Woila Creek and Tuross River, near Spring Mountain. Strong south-westerly winds pushed the fire into very rugged country around Woila Mountain. A wind change to the north-west and westerly on 23 September fanned a large front towards the headwaters of the Deua River, where it burnt in fuels accumulated since 1939. By 30 September, the fire had crossed the upper reaches of the Bumbo Creek, travelling 25 kilometres in two hours. There were spot fires at Bodalla. Thankfully, conditions eased on 2 October, and when the fire reached the coast at Dalmeny, firefighters quickly controlled it. However, it still burnt uncontained in the inland forests.

The Currawon Creek fire started on 19 September and was deliberately lit, believed to be by cattlemen illegally grazing on vacant Crown Land. The fire burnt many hectares in the Currawon area along the Budawang Range, finally stopping on the western side of the Clyde River.

On 23 September, somebody deliberately lit a fire for 16 kilometres along the Merricumbene fire trail. Two days later, it moved into the neighbouring inaccessible country, which had not burnt since 1953-54. It then reached cleared country west of Moruya, split into two fronts and headed to the highway in the north and into Wambam Creek in the south. The Merricumbene and Woila Creek fires continued burning as bad fire weather prevailed until December, eventually joining up.

Authorities declared a State of Emergency over southern New South Wales on 24 September as raging bushfires, fanned by 100-kilometre-an-hour winds, swept the region. The Currawon Creek fire was the worst, and another severe fire was just north of Batemans Bay.

Most of the fires were in the inaccessible country between Wollongong and the Victorian border. The situation at Bermagui was described as “explosive” by the local fire brigade. There were reports that somebody deliberately lit many of the fires. Two Sydney detectives were sent to the south coast to investigate reports that some of the fires were lit by farmers trying to burn off, although some were flare-ups of fires lit under permits early the previous month.

Lightning strikes started a fire in the upper reaches of the Clyde River. On 26 October, the fire quickly broke out around Pigeon House Creek under hot and dry north-westerly winds. The fire front split after leaving the forests and ran north of Milton and south of Ulladulla. Both fronts eventually burnt to the coast. The fire burnt the same country that experienced a hot fire in 1964-65, burning through prolific regeneration and growth of pioneer fire plants and wattles.

On 29 October, north of Batemans Bay, a fire destroyed five houses near Burrill Lake and one farmhouse at Verona, north of Bega.

The Blue Mountains, Illawarra and Sydney fires

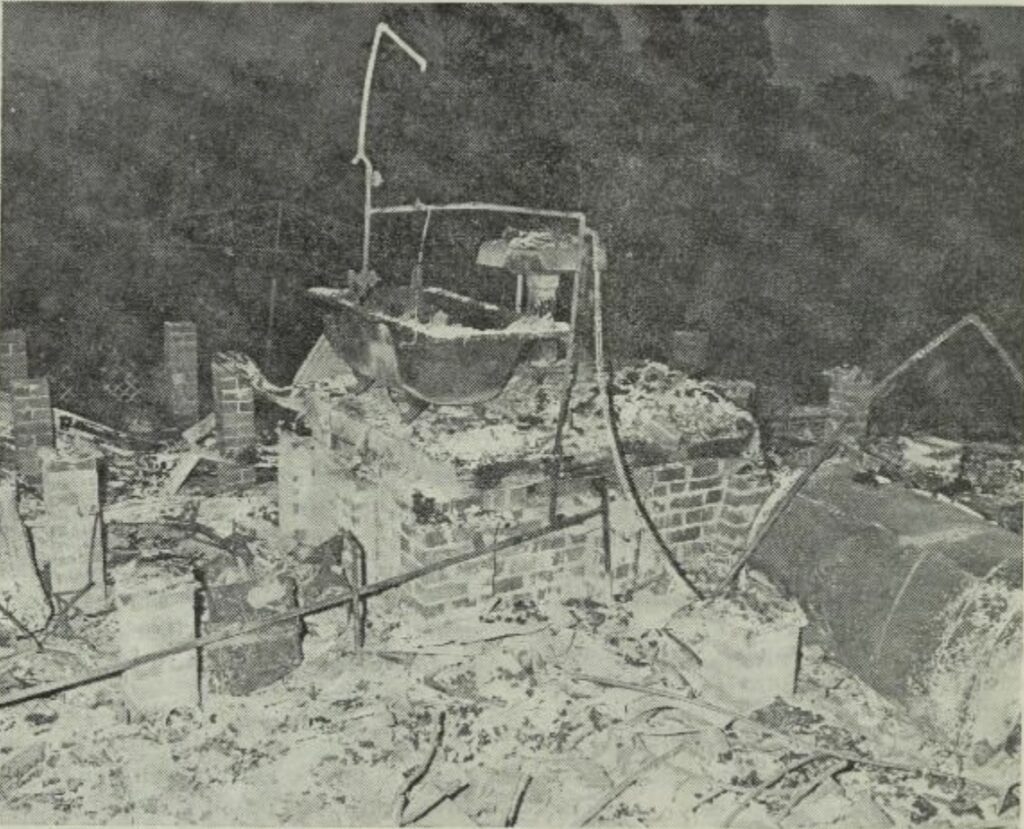

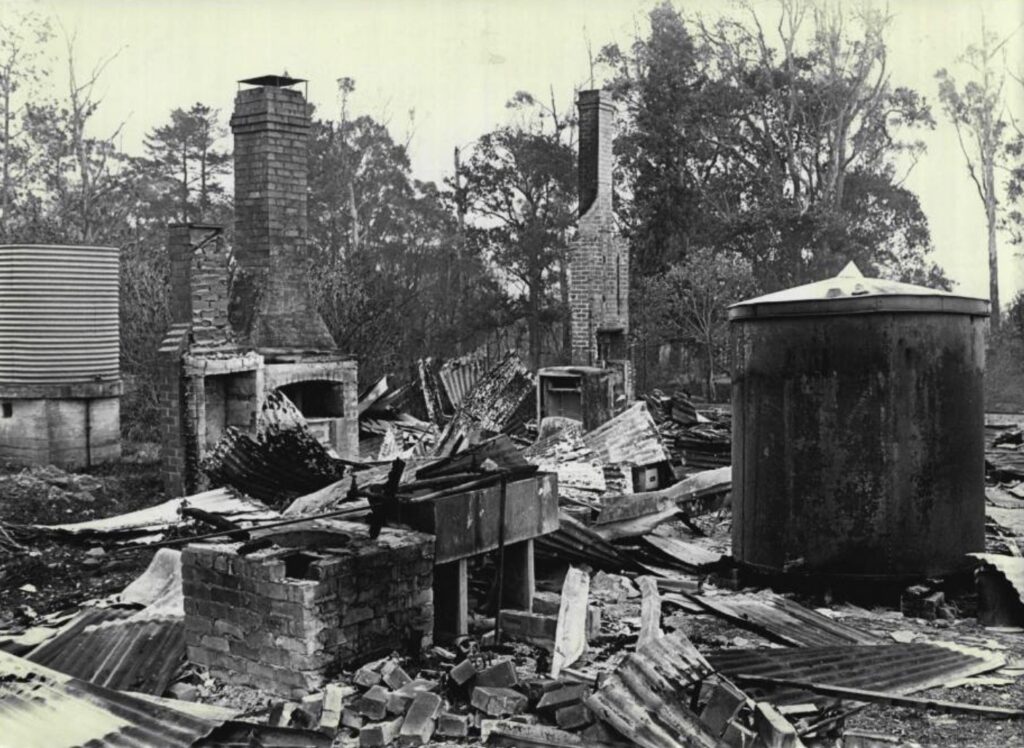

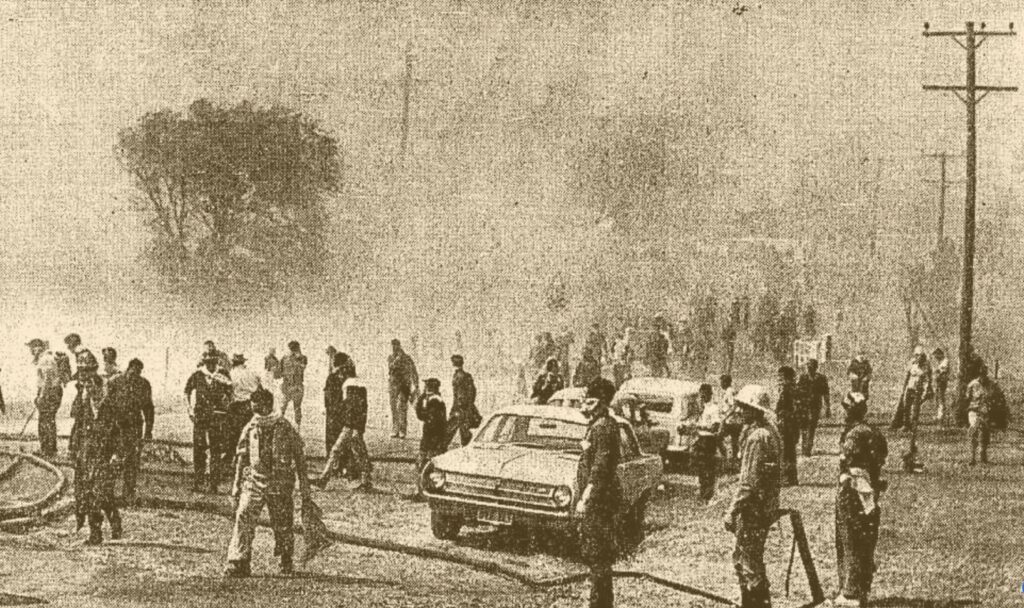

The state had numerous severe fire weather events during October and November. On 28 October, fanned by strong north-west winds, ignitions in the lower Blue Mountains erupted in flames on a searing day, plunging the area into a five-day state of emergency. More than 120 houses, the Blaxland shopping centre, cars and other buildings were destroyed. Moving cars were reported catching fire on the highway.

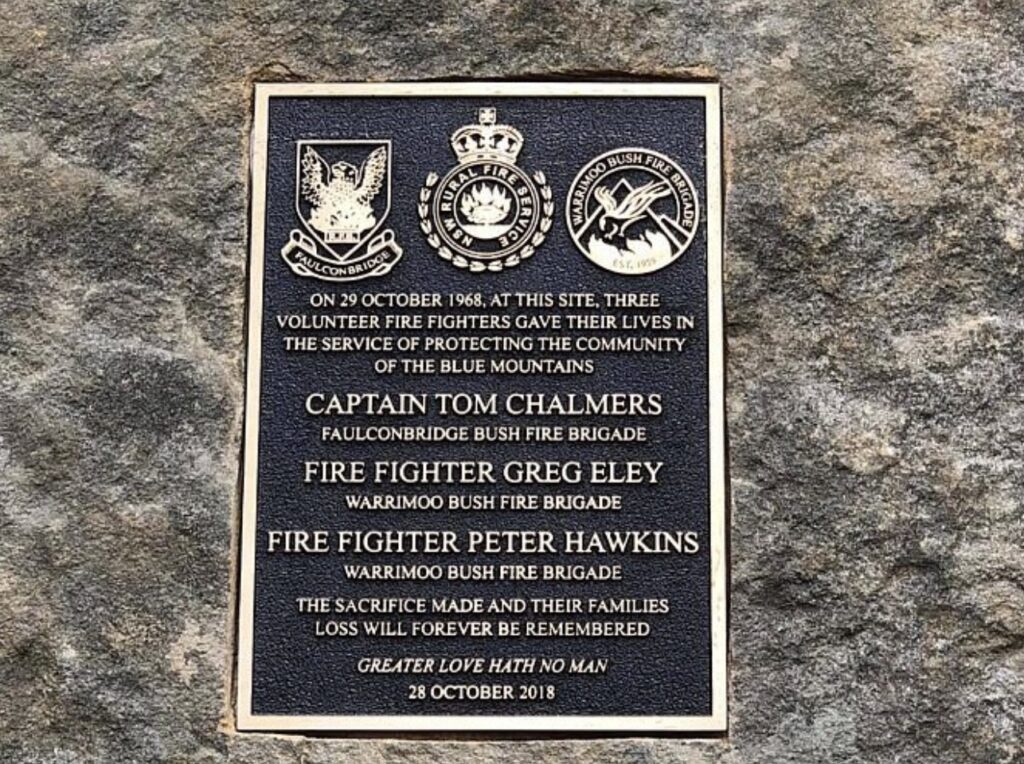

Tragically four people died – three volunteers collapsed while fighting the fires after a “freak ball of flame” engulfed them on Shaw’s Ridge fire trail off the end of White Cross Road, Winmalee. Neighbours also found a Blaxland resident in the kitchen of his burnt-out home.

The mountain was ablaze. The fires raged for 68 days destroying 150 buildings. Blaxland bore the brunt of the carnage. Not one tree remained alive on either side of the town. The only ones that survived were in the main street of the town.

The fire started and followed a predictable path similar to the wildfires only 11 years earlier. It jumped the highway near the R.A.H. Smith Waterhole Garage and General Store close to the Faulconbridge Railway Station. It quickly passed through the houses in its path, roared through Sassafras Creek, raced up the ridge, and came out at Martin Place. A front headed eastwards and, a few minutes later, raced up to Davies Avenue in Springwood. It continued to Blaxland, engulfing houses in minutes. The whole length of the Great Western Highway on the southern side of Faulconbridge to Emu Plains was dotted with smouldering houses, cafes and shops.

A similar story unfolded in the Illawarra region and Sydney’s northern and southern suburbs the next day. In the suburbs of Wollongong, 27 houses were burnt to ash, and one person died. A massive fire at Kuringai Chase, north of Sydney, engulfed 40 volunteer firefighters. They had to huddle together for nearly two hours in a burnt out clearing as the fire surrounded them. They eventually guided themselves to safety along a fire trail.

Fires in south-east Queensland and along the central and north coast of New South Wales

By mid-September, conditions were very dry in south-east Queensland. Several fires started on 25 September near the outskirts of Nerang and between Enoggera and Mitchelton. A total fire ban was declared for the south-east region south of Bundaberg for 48 hours from 18 October. A large fire had burnt uncontained through the Numinbah Valley at Lamington National Park in the week prior, and there were concerns about its further development, with weather conditions expected to deteriorate later that week. Department of Forestry staff and heavy machinery resources were called upon to save three homes at Ferny Grove in Brisbane.

On 25 October, families were evacuated from their homes when a fire near Coolum was out of control. Two days later, many areas in the southern part of the state were alight under the dry, hot weather and squally winds. A new fire at Lamington National Park jumped Nixon Creek and raged up the forest’s western slope. There were also fires at a forestry reserve near Mapleton and grass fires on Brisbane’s outskirts. Over 37 fires were burning on a bad day on 28 October, with the next day forecast to be a day of very high fire risk.

By the end of the month, there were over 500 firefighters attending fires throughout the south-east region. A fire started on Fraser Island near Happy Valley on 30 October, and while it initially was of little threat to the small tourist settlement, it soon burnt through part of one of the state’s great timber resources in the centre of the island. Fires also destroyed two of the state’s largest banana and pineapple plantations near Dayboro.

Early November was just as bad for south-east Queensland, despite falls of nearly three inches around Caloundra and Nambour. Fifteen Shires were still in a state of emergency. There were 28 grass fires in Brisbane’s wind-whipped heat on 12 November. Strong northerly and westerly winds combined with near 40-degree temperatures were a major concern. Brisbane suffered under its highest November temperature for over 50 years on 14 November, reaching 39.60C. Luckily a cool south-easterly wind change in the early evening brought much-needed relief.

The forests south of Mt Nebo exploded in flames, believed to be due to neglect by campers near Lake Manchester, on 18 November, prompting a massive response from Department of Forestry employees trying to prevent the fire from threatening the small township of Mt Nebo. Unfortunately, the situation worsened on 19 November when over a dozen fires were out of control. Troops, police, jail prisoners, hundreds of forestry workers and volunteers battled throughout the night to control the fires. Brisbane reached a 55-year record temperature of 40.80C during the day and the next. In the Gold Coast hinterland, fires raged from the border to Mt Tamborine, west to the Beechmont Range and east to Mudgeeraba.

Fires started in late September on the north coast of New South Wales, with outbreaks near Kempsey, through Coffs Harbour to Grafton, and further inland around Casino.

The dry conditions continued into November. The hot weather saw many fires along the eastern seaboard and inland valleys of New South Wales’ central and north coasts. A thick dust and smoke haze blanketed the north coast for over a week. Vic Eddy was the acting Sub-district forester at Kyogle when the fires started. Kyogle was at least 22 kilometres from the fires, but the smoke was so thick in town, his wife couldn’t see the houses next door. When David Hynd arrived during the week to take over, he saw the district hidden by a pall of smoke.

In those days forestry staff did not have two-way radio communications. They used borrowed High Frequency radio units, but they only worked if you could actually see the person you wanted to speak to. It wasn’t all that long afterwards that Very High Frequency (VHF) radios became standard equipment.

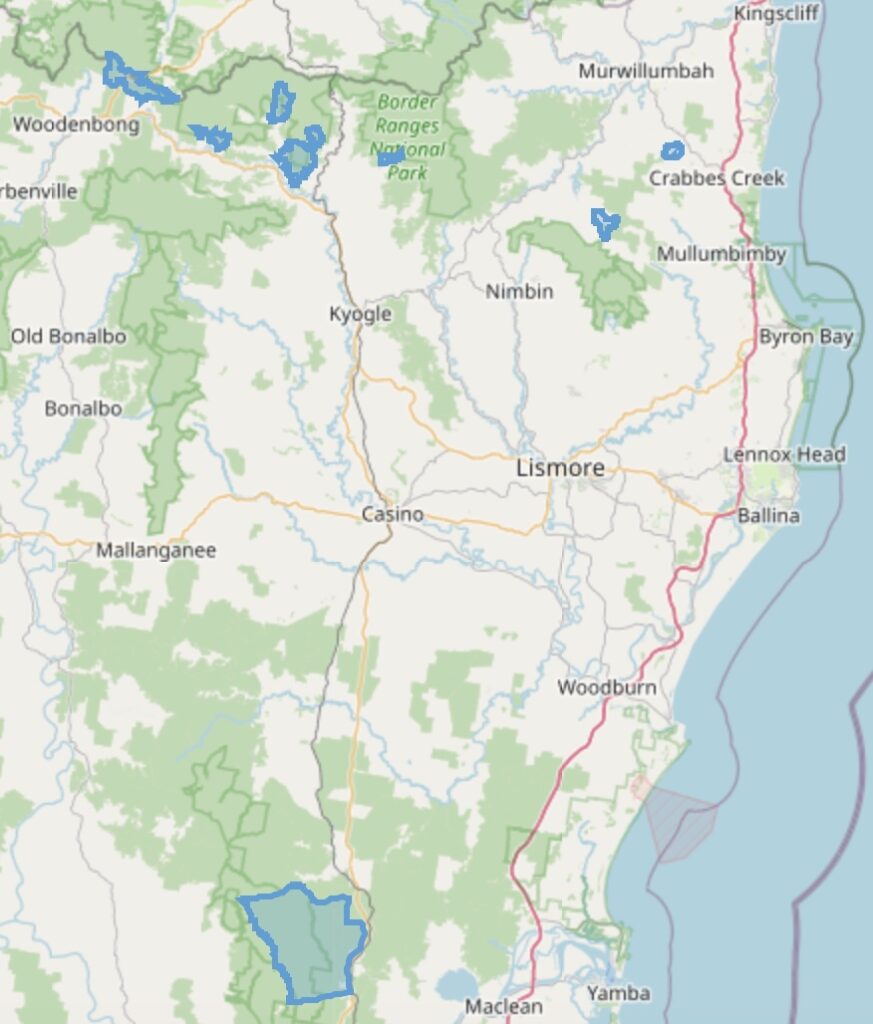

Hot weather with “centenary” temperatures hit the far north coast on 14 November, where strong westerly winds renewed the outbreaks of major fires on the north coast, and all available forestry employees in the area were engaged in fighting the fires. The fires were at Tabbimoble, Whian Whian State Forest, Mt Lindesay, Graham’s Creek, Camira Creek, Unumgar and Mount Marsh. While most started that day, the Unumgar fire had been burning for over three weeks. On Sunday, 17 November, five fierce fires began in the Casino District. One was lit by a passing “chap on a horse” close to Toonumbar State Forest which tied up forestry workers for over a week trying to round up the fire. They knew who lit the fire but had no proof. The culprit had a reputation for lighting grass fires that would burn “safely” into Richmond Range State Forest.

A fire spotting flight from Casino was abandoned when no more than ten minutes after take-off, the pilot hadn’t seen the ground for five minutes. His navigator, forester Col Nicholson, was only too happy to get back on the ground.

Monday, 18 November, was a killer day as bushfires raged out of control from Newcastle to just north of Bundaberg in Queensland. Fanned by hot westerly winds and very low humidity, there were many fires in the tinder dry country. That day’s primary fire was an unstoppable crown fire that ripped through the pine plantation in Banyabba State Forest.

Workers were fighting a fire about one kilometre west of the pine plantation. They realised a spot fire had just taken hold near the edge of the plantation, so an immediate attack was launched.

The fire roared into the forest, spotting half a mile ahead of the fire front after an unsuccessful backburn. It was only a matter of minutes after the pine ignited that it became a crown fire. The Summerland Way was cut on a mile-long front, closing the road to traffic. In less than 24 hours, the fire turned the pine forest into blackened trunks.

Nearly 1,000 hectares of the plantations, or two-thirds of the forest, were burnt at an estimated loss of $8 million. For a month afterwards, train drivers travelling past the forest reported fresh fires from smouldering stumps buried under blankets of fresh pine needle fall. Vic Eddy flew over the plantation on a fire spotting flight after the fire and could see the multiple paths of the fire through the plantation – black strips with brown edges and little islands of green.

The District Forester at Casino reported fighting nine large fires during sweltering weather. They were fearful the severe fire weather would continue and deny them the tenuous control they had over several dangerous fires. Thousands of hectares of state forest and private property had already been burnt. All the major north coast centres recorded very high temperatures – Casino reached 42.70C, its hottest day for 24 years and Lismore had its hottest day in 40 years. Humidity was only 10 per cent at 3 pm. In the Kyogle Sub-district, there was an unofficial record of 47oC and 8 per cent humidity.

Two large fires at Blue Knob near Nimbin were brought under control before Monday 18 November. However, they broke containment lines before dawn that day, fanned by strong south-westerly winds and were still burning out of control at the end of the week.

The hot westerly winds pushed raging fires around Newcastle, threatening Wakefield, Barnsley, Killingworth, Fassifern, Teralba, Kearsley, Kitchener and Abernethy. Near Bulahdelah, a sawmill was destroyed, and another was severely threatened when logs caught fire. At the height of the fire, 14 homes were threatened in Bulahdelah, as well as the golf and bowls clubs and a caravan park.

By Wednesday, 20 November, the fire position in the Casino and northern rivers areas was critical. Forestry Commission resources were stretched beyond their maximum limits, and they brought in the Grafton Civil Defence to help protect the remaining unburnt areas of Banyabba State Forest. A big fire in the Richmond Range nearly burnt out a sawmill in the forest. Forest workers recorded flame heights as high as 70 feet. Firefighters tried to control another large fire at Ewingar, but two other fires in the same area burnt unattended. The same situation prevailed at Toonumbar, where firefighters struggled to contain a large fire in recently logged rainforest while another three fires raged freely.

At Cessnock, five homes, two sawmills, two wineries, many sheds and buildings, miles of fencing and an unknown number of livestock were destroyed. An elderly man was severely burnt when his car burst into flames after it jumped the road. The worst hit areas were Mulbring, South Cessnock & Pokolbin. There were also fires at Thornton, Tarro, Broke, Milbrodale, Kearsley, Neath, Kurri Kurri, Paxton, Abermain, Bulga and North Rothbury. The worst fire roared through thick bush near Pokolbin and spread overnight towards Broke.

At Lithgow, soldier prisoners from Newnes Prison farm and firefighters combined to fight several large bushfires, their biggest since 1957. One fire on the mountainside north of Lithgow threatened an Army explosives dump. The Forestry Commission also reported a fire on a 15-mile front near Mount Wilson.

Hot weather persisted until Thursday, 21 November, and fires continued to rage out of control on the far north coast exacting huge losses. In the Casino and Kyogle districts, there were more than 30 fires, with many still out of control, mainly due to the lack of resources to fight the fires. Fanned by stiff north-westerly winds, the worst fires were at Tabbimoble and Ewingar State Forest west of Baryulgil, and at Toonumbar State Forest at the head of Iron Pot Creek. There were also two large fires in Yabbra State Forest near Woodenbong and one at Mt Lindesay.

Vic Eddy recalls at one point south of the Toonumbar fire, he had to stop the local bush fire brigade lighting a backburn on the opposite side of the road to where the fire was coming from.

A forestry perspective in the valley

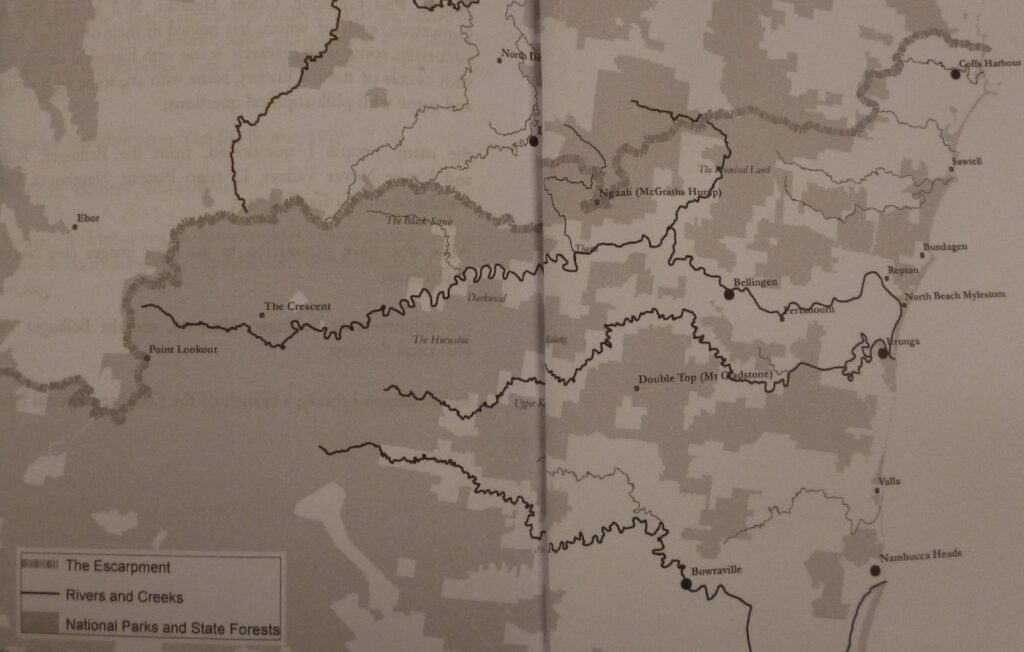

The rest of this blog will focus on the fires in the Bellinger Valley during the 1968 fire season. I was fortunate to manage the forests in the valley in the early to mid-1990s. When I arrived, I saw majestic, even-aged blackbutt regrowth on the Scotchman Range and the ranges south of the South Arm, bordering and extending into the Nambucca Valley. The trees were just over 20 years old, a by-product of the fierce 1968 fires, but they were forming the first glimpse of a majestic forest into the future. While at that time, they exhibited a scraggly form, much like a gangly teenager on the cusp of puberty, they were beginning to show the potential to develop into fine specimens in adulthood.

Alan Ruge was the Urunga District Forester at the time, and he outlined how devastating the 1968 fires were. Much of the forests along the Horseshoe had been logged in the early 1960s and were receiving regeneration and silvicultural treatments. Every spur running off the central range had a road to access the fine stands of blackbutt on the ridgetop, the blue gums and tallowwoods on the slopes, and if the gradient allowed, brush box further downslope. The Forestry Commission had silviculturally treated some seedling regrowth from the logging operations. Over three days in November 1968, most of it disappeared – about 30 per cent of the state forests were burnt, destroying large swathes of critical regeneration. They were the trees and resources for the future. The rejuvenation process had to start again.

In the early 1990s, the valley experienced similar drought conditions as in 1968. The worst time was in late August and early September 1991. We were close to having a similar fire experience to that of 1968, but fortunately, no big fires started during the windy conditions. We were also lucky to dodge a bullet in January 1994 when similar hot but relatively high-humidity weather occurred without the strong winds. It didn’t stop a holocaust in the outer suburbs of Sydney and the Hunter Valley, where large areas burned and many houses were destroyed.

One of the major problems in the Bellinger Valley (and elsewhere in Australia) is the propensity of farmers and forest lessees to carry out their regular burning-off operations. The problem is their repeated failure to take reasonable precautions when doing so. Either they deliberately left the fires uncontained to burn in the forest, or their fires escaped their properties after poor supervision and control. In most cases, when questioned about the fire they would invariably answer that it was last seen burning safely towards state forest. In 1968, Forestry Commission reports claimed that 92 per cent of the fires they attended in the Coffs Harbour District originated outside of state forests. The first 50 fires in forestry areas in the Casino District were traced to human carelessness.

To prosecute for illegally lighting a fire there had to be an admission or the culprit had to be caught in the act. Otherwise, the culprit had “witnesses” that he was somewhere remote from where the fire started at the time.

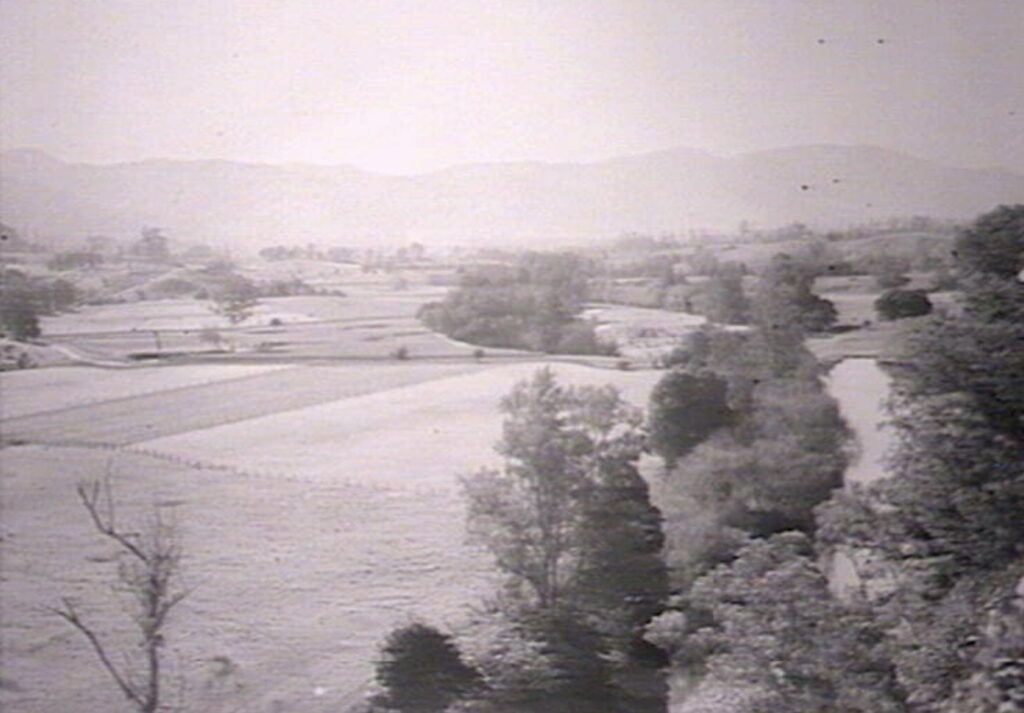

The farming areas in the Bellinger Valley occupy narrow bands of cleared country bordering the river and creeks. Outside these areas, the land merges into steeply rising slopes, forested ridges, and spurs, spreading like fingers between the rivers and creeks on the valley floor.

The state forest areas cannot be effectively isolated from the private properties because the boundary location is halfway up a ridge and not accessible by tracks. Also, the predominant east-west orientation of the forest areas provides the potential for long fire runs under adverse weather conditions. This problem can be addressed with prescribed burns, but the areas near the private property boundaries are problematic without the tracks.

Neighbouring landowners who used their forested areas for winter grazing burnt them when they mustered their stock during spring, aiming to improve grazing capacity by decreasing undergrowth, encouraging grass and reducing tick numbers. Unfortunately, the landowners conducted their burns just when the weather warmed up, and uncontained fires can be challenging to control without any containment objectives. These fires are lit on the lower slopes on private property and commonly allowed to continue upslope into the state forest to damage regeneration and young trees. Earlier burning would suit forest management aims but consumed limited available grass just when the grazier most needed it.

When the burns are carried out as late as possible before the introduction of the permit season on 1 October and are allowed to escape, the Forestry Commission is belatedly advised that the “fire got away”. As the Fire Control Officer in 1968 lamented, and still relevant over twenty years later when I was around, one of the most common causes of damaging bushfires was a failure to effectively mop up and patrol a burn.

The fires in August – September 1991 were during a drought period where we had to deal with a number of the grazier burns that had entered state forest. But the big one was when a fire was deliberately lit on the northern side of Horseshoe Road along the Scotchman Range for about 15 miles. I was travelling home that late afternoon from Oakes State Forest at the head of the valley when I chanced upon the fire. I reckon I missed the culprit by no more than half an hour. While the fire was initially doing an excellent job in the afternoon and that night, we had strong winds forecast later in the week, and we needed to contain the fire.

We tried to tie up the fire to control lines by carrying out a backburn operation along Kirklands Road the next day in relatively unfavourable conditions, which was unsuccessful. We finally controlled the blaze averting a disaster before strong dry winds arrived, but not before committing a large number of resources.

In the process, we were attacked by the hippies on private lands in the Leans Creek catchment adjoining the forest when we used aerial burning to close out the fire to containment lines and thoroughly burn out the area. They couldn’t understand the concept of using fire to control fire and firmly believed all fires are destructive fires. The only fires they hear of, see, or encounter are conflagration fires out of control and thought they could not be managed.

I found an elaborate dope plantation cut into a gully when I had to go for a walk after a spot over on our backburn. It explained why we had so many visitors on motorbikes during the day who offered no assistance, thanks, or even a hello. Consequently, I wasn’t upset we burnt out the plantation and plastic piping after we lost the backburn across the track.

It was a busy time for us. We also had fires at Viewmont State Forest, plus fires in the neighbouring Nambucca Valley to the south – on Kilprotay Road at Thumb Creek State Forest, Orange Tree Road at Irishman State Forest, and Nambucca State Forest.

The three horror days

There was an exceptional heatwave in north-eastern New South Wales in mid-November 1968 as temperatures soared and there was no relief for firefighters. In Bellingen, Sunday, 17 November was 380C, Monday was 41.60C, Tuesday exceeded their previous highest record set in 1952, hitting 43.30C, and Wednesday was 410C. For those latter three days, the Bellinger Valley experienced weather conditions that firefighters call “blow up” days. This consists of strong, gusty north-west to south-west winds, high temperatures and very low humidity. In essence, the furnace-like conditions produced extreme fire danger conditions. The previous fires kept burning, dying down for days and flaring up as the weather allowed.

A fire near Girralong in the upper Nambucca Valley, escaped from a permit burn, roared into life and quickly spread up the slope into Oakes State Forest on 18 November towards the Horseshoe Road. There were large areas where the fire spotted from spur to spur, crowning in the drier blackbutt forests and burning less fiercely in the forest on the slopes with a more mesic understorey.

In the Bellinger Valley, the Horseshoe Road follows the Scotchman Range between the two arms of the Bellinger River. Under the influence of the strong winds and topography, the Oakes fire moved in many directions. Four bulldozers and about 30 Forestry Commission staff tried to contain the fire the next day without success.

On Wednesday, 20 November, the fire spread, travelling 15 kilometres between 2 and 5:30 pm in Irishman State Forest on the Bellbucca Range, which divides the Bellinger and Nambucca Valleys. This was some ten times faster than under normal conditions.

About 15 kilometres long, a new fire break was built from the Horseshoe to Bellinger River at Upper Thora. Because the main fire had split in two major directions, another trail was constructed south into Kalang as the fire continued to burn through the Gladstone State Forest. This fire supported the greatest concentration of firefighting machinery and staffing ever assembled in the Bellinger Valley.

With the fire getting close to the Bellingen Hospital, the staff made plans to evacuate patients to Coffs Harbour in case the fire swept across Hospital Hill. Pregnant women due to give birth over the next few weeks were induced in preparation for the evacuation.

By Thursday, 21 November, the fire was burning fiercely along the ridges on each side of the Kalang River and in the Brinerville area of the Upper North Arm. A major backburn was also carried out from Spicketts Creek that night under trying conditions.

Jack Young, who lived in isolated river flats near the headwaters of the Bellinger River, was reported missing after failing to return home. The fire near the Horseshoe Bend cut him off. He managed to burn an area around his position to act as a break and eventually returned home safely.

Firefighting efforts were hampered on 25 November – another hot day with gusty winds. With fires still active, more fire breaks were cut or opened to contain them. While a fire had already caused considerable damage to the young regrowth in Gladstone State Forest, the concern was the continual spread eastwards towards Newry State Forest, which supported some of the finest even-aged blackbutt regrowth stands in the region.

For three days from 27 November, a dense smoke haze covered the whole Bellinger Valley. Visibility was limited at times to just a “couple hundred yards”. To emphasise the dry conditions, parts of the South Arm had run dry for the first time in over 50 years, and the water levels in Hydes Creek were also the lowest seen in living memory for long-time residents. Whichever direction you headed from Bellingen there were fires burning.

A plan to build a firebreak from one arm of the river to the other across the Scotchman Range as a last stand to stop the fire from reaching Bellingen was pleasantly disrupted by rain on 3 December. The break was an ambitious and risky undertaking over about nine miles, climbing a knob over 600 metres at the top of the ridge. Forestry staff managed to carry out a backburn to Lane’s Creek and mop up, easing the danger. They also lit a fire from No 1 Logging Road to Raymond’s property at Kalang. They were aided by Civil Defence personnel.

An uncontained fire in Dorrigo State Park fire blew up off Dorrigo Road on the lower slopes of the escarpment. It quickly spread in several directions across the Little North Arm Road. Another fire around McGrath’s Hump started on Wednesday, 27 November, providing a spectacular scene of bright embers that night. A bulldozer constructed a very steep new break along Buffer Creek across the Hump to Little North Arm to prevent the fire from spreading north into rugged country of the northern range near Mt Moonbil.

Locals who had lived in the valley all their life said that they only ever saw a fire on McGrath’s Hump once or twice before.

The fire moved to the eastern side of the Hump into the Gordonville area, and a few isolated farmhouses were under threat. By Thursday morning, the fire was bearing towards the APM plantations in the Gleniffer-Valery area.

Under the strong winds and high fuel loads, the fire was crowning and spotting ahead of the fire front. There were fears the fire could quickly burn out the valuable plantations. Luckily, the weather conditions eased by the end of the week, with cooler south-easterlies and higher humidity reducing the fire threat, allowing containment.

In early December, fires also swept through almost 60,000 hectares of state forest over the previous ten days in the Macleay Valley to the south.

The tragedy at nearby Conglomerate State Forest

The Editor of the Northern Star newspaper wrote on Tuesday, 19 November:

“If any blessings can be counted from the scale of the disaster, they come from the absence of tragedy amongst the region of firefighting heroes”.

Unfortunately, he was too quick to summarise the terrible fire situation, as fires continued to cause havoc in most forests along the coast.

Coffs Harbour had its highest-ever recorded temperature on 18 November at 44.40C. It was so hot school children were sent home, and more than 50 golfers withdrew from Coffs Harbour’s largest sporting event – the annual Festival of Golf.

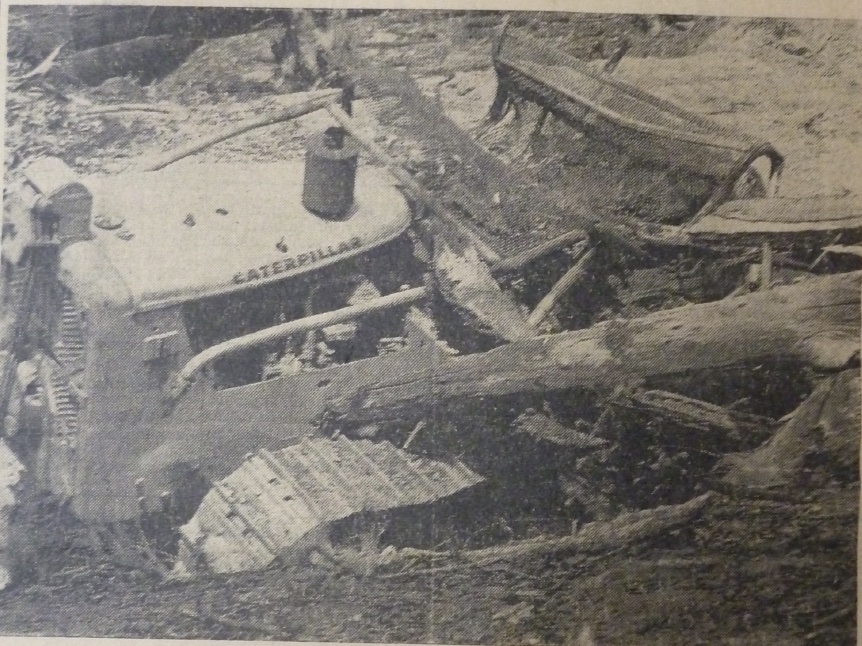

A major fire started south of Glenreagh that day, burning out most of the western extension to Conglomerate State Forest and made a run for high-quality blackbutt stands in Sherwood Creek, about 22 kilometres south-west of Woolgoolga. The next day, a crew of six men and a bulldozer were the initial attack force to stop the forest fire. They worked all night, and in the morning, they all clambered onto the dozer designed to seat two to climb the steep slope through the forest to their transport vehicle on the main road for the shift change.

Sadly, the scale of the disaster became apparent after a freak accident affected the entire crew. The strong hands of the men not seated grasped the overhead canopy guard, two sitting on the armrests, and the other two stood on the logging winch at the rear of the driver’s seat. As the dozer climbed the slope, it travelled through areas burnt by the fire. A partly burnt-out blackbutt tree fell across the tractor when they passed. The two on the log winch outside the protective canopy managed to jump clear, surviving the horror of what happened. Two of the crew were killed instantly, another died on the way to the hospital, and the other was seriously injured.

As well as worker’s compensation and endowments, a local public appeal raised $2,641 and was donated equally to each of the wives of the three men killed fighting the fire at Conglomerate State Forest.

The aftermath

At the start of December, with just one massive thunderstorm and over two inches of rain, the arrival of summer announced itself. The air was humid and the swollen afternoon clouds from the sea began to roll into the valley to deposit their moisture.

Up to three inches of rain fell in the next week to help extinguish the fires. Forestry resources were stretched during the disaster, and the assistance of the volunteer brigades and APM crews helped contain the fires and avoid further damage. The fire in Scotchman State Forest was the last to be put out. The major fire line that stopped the fire heading towards Bellingen, was only nine miles west of the town, a distance that could have been covered in only a few hours if the dry conditions had persisted.

In the mountainous timbered areas of New South Wales between the coast and the Great Dividing Range, bushfires of appreciable size have occurred before (and since) 1968. Big fires were in 1926, 1939, 1951-52, 1957, 1965, 1994, 2002-03 and 2019-20.

While there were gradual steps taken from 1950 for foresters to extend their influence in fire protection to lands outside of state forests, such as the formation of the Hume-Snowy Fire Protection Scheme (HSFPS) covering much of what is now Kosciusko National Park, the irregularity of fire seasons in eastern New South Wales made the task of maintaining enthusiasm and interest in fire prevention very difficult.

While there was a focus on fire trail construction, providing access alone was insufficient to cope with the problem of continuously building fuel levels. Under the direction of the FCNSW Fire Control Officer, Henry Luke and Alan McArthur, the first full-time fire control officer for HSFPS, they concentrated resources to carry out some prescribed burns. Luke also was instrumental in establishing Bush Fire Districts to manage the fire risk on the significant areas of vacant crown lands in the coastal and tableland areas, particularly after the disastrous fires in the Blue Mountains in December 1957 and the success of the HSFPS.

The Chatsbury-Bungonia fire of March 1965 in the Southern Tablelands highlighted problems. It burnt 220,000 hectares between Goulburn and Wollongong, leaving a path of destruction unprecedented up to that time. The damage included 87 homes, 24 shearing sheds, 18,000 sheep, 2,400 cattle and 59,000 hectares of lost pasture.

At the same time, under similar weather conditions, further south, the HSFPS had its first major test with the Tumut Valley fire. While it burnt 80,000 hectares and property losses were minor, it reinforced the need for better co-ordinated fire control and more controlled burning to be expanded across the forested areas east of the Divide.

A special conference was convened after the 1968-69 fire season to discuss fire management in the state. Recommendations were made to the Minister, and there were amendments to the Bush Fires Act. The significant changes were a more centralised co-ordination and preplanning for large-scale fires, suppression and prevention activities in the eastern part of the state, and a retention of a decentralised council of bush fire brigades. These amendments gave precedence to planning for emergency fires and, for the first time, introduced prescribed burning as an essential part of prevention activities.

The Leader of the State Opposition asked in parliament that the government consider leasing firefighting planes from Quebec. The Canadian Province had 20 aircraft they used in firefighting. However, the State Bush Fire Committee had already investigated the use of similar aircraft and realised they would not be effective in New South Wales.

While foresters had begun the use of fire as a tool on intensively managed state forests in the 1950s, much of the work was remote from the public and not well publicised. They were eagerly awaiting the results of the new role of aircraft in Western Australian trials conducted by the CSIRO and the Western Australian Forest Department in 1967 to introduce landscape-scale prescribed burning in the foothill forests and extensive vacant crown land.

Finally, fire was no longer publicised as the enemy. It was now seen as a tool. The emphasis on highlighting the risks of fire escaping was given widespread publicity to stress the need for local government and other land management authorities to undertake prescribed burning.

By the time I arrived on the north coast, the Forestry Commission had a strongly equipped and highly trained workforce that had a high priority on carrying out extensive prescribed burning and could rapidly attack any fire outbreaks during the fire season.

Sadly, before I left the north coast, the seeds to dismantle a highly sophisticated and professional fire management force was already having an impact as we see the decline in professional fire management across the state over the last 30 years, which has culminated in more and more severe fire events, on a scale we saw in 1968.

Unfortunately, lessons hard won all those years ago are easily ignored and forgotten. The 1968 fires need to be front and centre in the minds of the new fire managers from the Emergency Services so they can fully understand the risks faced when fuels are not managed across millions of hectares, particularly as we are now seeing carbon fertilisation from higher CO2 levels in the atmosphere.

A final word

Like other parts of the north coast, the Bellinger Valley faced its worst heat and bushfires in the spring of 1968. Searing north-westerly winds produced temperatures a long way above the century in Fahrenheit for three days in succession. Firefighting units and volunteers fought desperately to save property and contain the roaring flames.

When people try and tell you the 2019-20 fire season was unprecedented, caused by climate change and fires starting earlier in the fire season, remind them of the horrific fire season of 1968-69 where wildfires started as early as June, roared into fireballs in early September and, under the influence of severe fire weather in October and November caused them to ravage the whole coast of New South Wales and south-east Queensland and severely burn up to two million hectares of forest.

A timely released blog, given the fires in the last days.

Lessons to be learned, now we just need to get the students (bureaucrats) to attend and listen.

Thanks Robert.

This is a most important article. Firstly, it debunks the foolish and dangerous notion that bushfires are caused by climate change. Secondly, it ensures that the events you describe go into the historical record, an authentic account by someone who was there at the time. I do hope, however, that your article ends up as hard copy, within covers, and is read by pollies, agency bureaucrats, “Fire Chiefs” and journalists.

One of the greatest problems for land and forest managers is that people have short memories for bushfire disasters. This is actually encouraged by our political leaders [“Put all that behind us, we can now move forward into a new and wonderful world etc”]. This forgetfulness is one of the factors that allows people to see every new bushfire disaster as being “unprecedented” and to ascribe it to some new fad like global warming.

By the way, the incident you describe of the forestry firefighters killed by a falling tree near Coffs Harbour, is poignantly covered by famous NSW forester Curly Humphreys in a story in the book “Firefighters – stories from Australian foresters”. Curly grieved for both the forests that had been destroyed in the fire and for the lost lives of the men, who he knew.

If anyone is interested in reading Curly’s story, please contact me.

Roger Underwood (yorkgum41@outlook.com).

I encourage anyone who is interested to get Roger’s book. It has some great stories from foresters about fire fighting experiences. It was especially poignant reading Curly’s story about the men who died fighting the fire and he adds a deeply personal and touching account of the events at the time.

Another informative read Robert of major landscape fires in 1968 when CO2 was at 323 ppm (now 422).

As an aside, another arsonist fire of note occurred in 1968 in Brisbane; https://www.hearsay.org.au/from-the-ashes-the-supreme-court-fire-of-1968/

AL, during my research for the story I googled the 1968 fires and didn’t get any hits at all online, the only hit on fires was that one! Interesting story, but a bit removed from what I was after.

Excellent article Robert.

It’s so frustrating that we as forest fire managers, went through a period of relatively good fire and fuels management from about the 1960s to about the late 1990s as a result of lessons learnt from bad fires in the 1950s and 60s. These fires resulted from a ‘fire protection and control’ policy (limited use of prescribed fire).

Since the late 1990s, good forest fire and fuels management has been dismantled, or degraded, with the dismantling of Forests Departments and the native forests timber industry.

It’s been replaced by water bombers and a scape goat called climate change, aided and abetted by clever silly academics. Even in southwest WA, we are falling behind in fuels management. I expect the next megafire will be in the karri forest region where there are big chunks of old fuels.

Robert, your account of the 1968 fires evoked some strong memories – particularly the bulldozer fatalities which reminded me of the risks and charmed life I’ve had.

In 1965 I tested the new CSIRO survival tent while trying to cross the head of the Tumut River Fire as it raced across the Alpine forests and plains between Yarangobilly and Adaminaby. We sheltered in the tents on a small patch moist creek bed only to discover later it was the only unburned area for some 14 km along the Tanangara Dam road.

Later on, I joined a fire crew constructing a hand tool line at night through regrowth ash forest resulting from fires in 1926. A sudden wind change forced us to take refuge on the burnt area and as we walked out of the fire, stags from the former forest crashed around us. No warning sounds – only a loud thump and a cascade of sparks as the large dead trunks hit the ground.

I had little experience on the North Coast prescribed burning programs. I carried out the first aerial prescribed burn in NSW on then Vacant crown land west on Moruya and on the Bemboka mountain in 1967. On the urging of Danny Christopher, in May 1968 I carried out two more aerial prescribed burns on Bemboka Mountain and Yankees Creek. The total area was around 10,000ha.

At the time the area was drought affected an we got an excellant burn of 80% with and average scorch height of 4m. Danny was convinced those burns saved the township of Bega from the widespread fires in October-November later that year.

I remember mapping the western edge of the 1968 fires from a light aircraft. We started on the southern edge near Bemboka and followed a near-continuous edge with only two short breaks near Camden, until we ran into restricted airspace somewhere south of Singleton.

The southern forests had been severely damaged by fire in 1952 and were considered worthless for timber harvesting and virtually unprotectable. However, Bob Richmond took over the aerial prescribed burning program and convinced the Commission the area could be protected and opened the way for the Eden woodchip industry and the subsequent regeneration of the forests for production forestry.

Thanks Phil for sharing your experiences from that time.

It is good you highlighted the effectiveness of the first aerial burning program on the south coast being instrumental in minimising damage and saving Bega – something I should have done more clearly in my story when referring to the Youri Gap fire passing through areas that had been burnt earlier in the year.

Also, that little bit about Bob Richmond’s influence is very important for historians writing about NSW fire and/or forest management.

Thanks Robert. Good article. I was at the Numinbah and Mt Nebo fires of 1968.

At Numinbah I witnessed a crown fire in a vine scrub, but later in the day was able to stop a running fire with a rakehoe line, because the area had been prescribed burnt earlier in the year. Rakehoe lines did not work on unburnt fuels. We had fire crossing roads through drains under the road. My survey team was cut off at the Numinbah forestry barracks, and had to light a ring around them. The night was full of the sound of trees burning down.

The Mt Nebo fires were also very difficult to control, after the very dry spring, following a “normal” wet summer. We were equipped with a couple of 44’s of water, and our water supply pump, three in the front, and standing room only in the back, hanging onto the drums, no overalls or special boots. I remember a night patrol, with Erwin Epp, when we saw a grey gum burning inside. Erwin walked over towards it, and I backed the Ute out of the way. The tree suddenly split up the trunk, and came across the road where the ute had been. We spent the rest of the night cutting a track around the head, which was still alight. My first 25 hour day.

The matter that the modern academics are missing is that in high drought index, and high fire danger, the whole forest is available fuel.

Thanks Ray for sharing your fire fighting experiences during those fires. I have been reminded by Queensland foresters that the 1967-68 summer experienced normal rainfall. There was a cyclone which crossed the coast 50 km north of Maryborough, turned to a deep low and dumped 28 inches at Ungowa on Fraser Island over two weeks in January. Yet the fuels dried out during the rest of the year.

Sadly, all the knowledge, wisdom and experience foresters and hardworking forestry employees gained at fires over many years is being totally ignored and lost and replaced with theoretical nonsense and the introduction of large machines that are ineffective against a landscape chock full of fuels and totally tinder dry towards the end of a drought. Consequently, they are clueless on how to respond when the inevitable severe fire weather arrives because they are totally unprepared on how to deal with the situation.

Unfortunately, and I speak for NSW, they were unprepared in 1968 and suffered the consequences. However, they made amends in subsequent years to develop a highly-trained fire fighting force supplemented by an active fuel management program.

People responsible for the shambles today should be held accountable and do not deserve to hold positions of authority that denigrate and totally ignore the past successful fire management practices.